Out of the long catalog of Emperors from ancient Rome, there are those who, for one reason or another, stand out amongst their predecessors and successors. Whilst some, such as Trajan or Marcus Aurelius, have become famous for their astute ability to rule their vast domains, there are others, such as Caligula and Nero, whose names have become synonymous with debauchery and infamy, going down in history as some of the worst Roman emperors we know.

Table of Contents

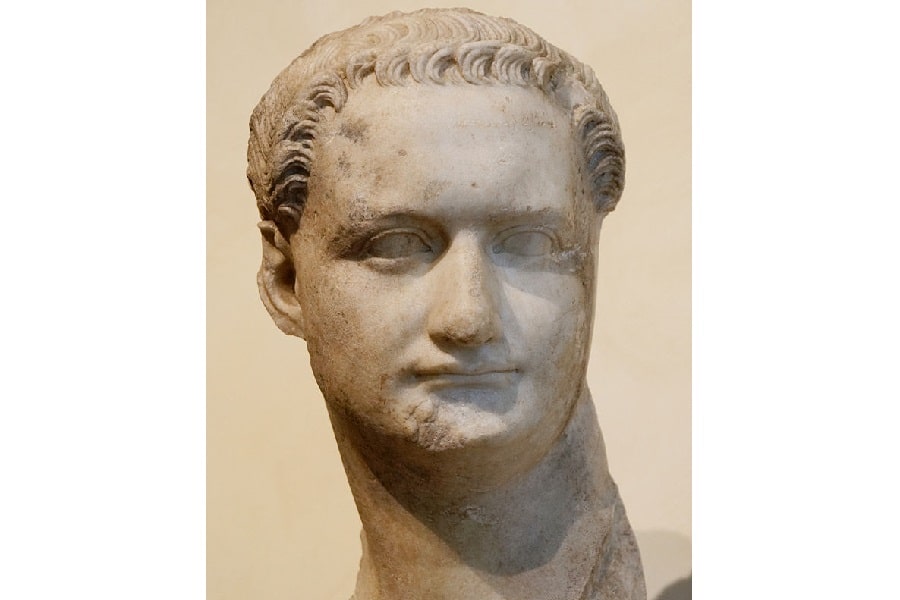

Caligula (12-41 AD)

Out of all the Roman emperors, Caligula probably stands out as the most infamous, due not only to the bizarre anecdotes about his behavior but also because of the string of assassinations and executions he ordered. According to most modern and ancient accounts, he seems to have actually been insane.

Caligula’s Origins and Early Rule

Born on August 12 A.D, as Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, “Caligula” (meaning “little boots”) was the son of the famous Roman general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, who was the granddaughter of the first Roman emperor Augustus.

Whilst he apparently ruled well for the first six months of his reign, the sources suggest he subsequently fell into a permanent hysteria thereafter, characterized by depravity, debauchery, and the capricious killing of various aristocrats who surrounded him.

It is suggested that this abrupt change in behavior was brought about after Caligula believed somebody had tried to poison him in October 37 AD. Although Caligula became seriously ill from consuming an apparently tainted substance, he recovered, but according to these same accounts, he was not the same ruler as before. Instead, he became suspicious of those closest to him, ordering the execution and exile of many of his relatives.

Caligula the Maniac

This included his cousin and adopted son Tiberius Gemellus, his father-in-law Marcus Junius Silanus and brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus, all of whom were executed. He also exiled two of his sisters after scandals and apparent conspiracies against him.

Besides this seemingly insatiable desire to execute those around him, he was also infamous for having an insatiable appetite for sexual escapades. Indeed, it is reported that he effectively made the palace a brothel, replete with depraved orgies, whilst he regularly committed incest with his sisters.

Outside of such domestic scandals, Caligula is also famous for some of the erratic behavior he exhibited as emperor. On one occasion, the historian Suetonius claimed that Caligula marched a Roman army of soldiers through Gaul to the British Channel, only to tell them to pick up seashells and return back to their camp.

In a perhaps more famous example, or piece of trivia often referenced, Caligula reportedly made his horse Incitatus a senator, appointing a priest to serve him! To further aggravate the senatorial class, he also donned himself in the appearance of various gods and would present himself as a god to the public.

For such blasphemies and depravity, Caligula was assassinated by one of his praetorian guards in early 41 AD. Since then, Caligula’s reign has been reimagined in modern films, paintings, and songs as an orgy-filled time of complete depravity.

Nero (37-68 AD)

Next is Nero, who along with Caligula has become a byword for depravity and tyranny. Like his evil brother-in-arms, he began his reign rather well, but devolved into a similar type of paranoid hysteria, compounded by a complete lack of interest in the affairs of the state.

He was born in Anzio on the 15th of December 37 AD and was descended from a noble family dating back from the Roman republic. He came to the throne in suspicious circumstances, as his uncle and predecessor, the emperor Claudius, was apparently murdered by Nero’s mother, the empress, Agrippina the Younger.

Nero and His Mother

Before Nero murdered his mother, she acted as an advisor and confidant for her son, who was only 17 or 18 when he took the throne. She was joined by the famous stoic philosopher Seneca, both of whom helped to initially steer Nero in the right direction, with judicious policies and initiatives.

Alas, things fell apart, as Nero became increasingly suspicious of his mother and eventually killed her in 59 AD after he had already poisoned his stepbrother Britannicus. He aimed to kill her via a collapsible boat, but she survived the attempt, only to be killed by one of Nero’s freedmen when she swam to shore.

Nero’s Fall

After the murder of his mother, Nero initially left much of the administration of the state to his praetorian prefect Burrus and advisor Seneca. In 62 AD Burrus died, perhaps of poison. It was not long before Nero exiled Seneca and set off on a slew of executions of prominent senators, many of whom he saw as opponents. He is also said to have killed two of his wives, one by execution, and the other by murder in the palace, apparently kicking her to death whilst pregnant with his child.

Yet, the anecdote with which Nero is perhaps best remembered is when he apparently sat watching as Rome burned, playing his fiddle when a conflagration started somewhere near the circus maximus in 64 AD. Whilst this scene was likely a complete fabrication, it reflected the underlying perception of Nero as a heartless ruler, obsessed with himself and his power, observing the burning city as though it was his play set.

Moreover, these claims of emperor-instigated arson were made because Nero commissioned the construction of an ornate “Golden Palace” for himself in the aftermath of the fire, and an elaborate reimagining of the capital city in marble (after much of it had been destroyed). Yet these initiatives bankrupted the Roman empire quickly and helped lead to revolts in the frontier provinces that promptly encouraged Nero to commit suicide in 68 AD.

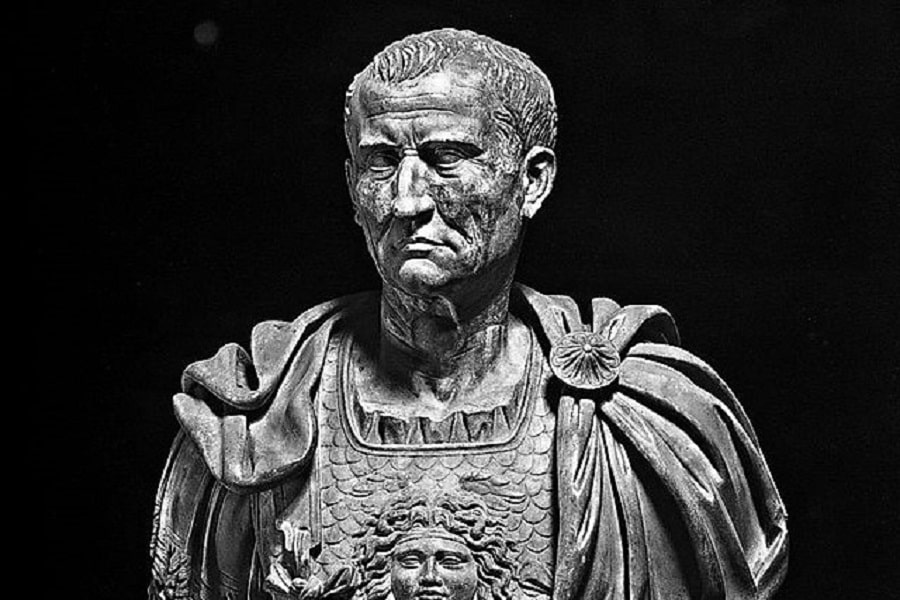

Vitellius (15-69 AD)

Whilst certainly not as famous to people nowadays, Vitellius was reportedly just as sadistic and wicked as Caligula and Nero, and for much of the medieval and early modern period was the epitome of a terrible ruler. Moreover, he was one of the emperors who reigned during the “Year of the Four Emperors” in 69 AD, all of which are generally considered poor emperors.

Vitellius’s Decadence and Depravity

His primary vices, according to the historian Suetonius, were luxury and cruelty, on top of the fact he was reported to be an obese glutton. Perhaps it is darkly ironic, then, that he apparently forced his mother to starve herself until she died, in order to fulfill some prophecy that he would rule longer if his mother died first.

Moreover, we are told that he took great pleasure in torturing and executing people, particularly those of high rank (although he is also reported to have indiscriminately killed commoners as well). He also went about punishing all those who wronged him before he took charge of the empire, in grossly elaborate ways. After 8 months of such iniquity, a rebellion broke out in the east, headed by the general (and future emperor) Vespasian.

Vitellius’s Gruesome Death

In response to this threat in the east, Vitellius sent a large army to face this usurper, only for them to be decisively beaten at Bedriacum. With his defeat inevitable, Vitellius made plans to abdicate but was prevented from doing so by the praetorian guard. A bloody battle amidst the streets of Rome ensued during which he was found, dragged through the city, decapitated and his corpse thrown in the Tiber river.

Commodus (161-192 AD)

Commodus is another Roman emperor well known for his cruelty and evil characteristics, helped in no short measure by Joaquin Phoenix’s portrayal of him in the 2000 film Gladiator. Born in 161 AD to the revered and widely praised emperor Marcus Aurelius, Commodus is also characterized by infamy for bringing the era of the “Five Good Emperors” and the “High Roman Empire” to an ignominious end.

READ MORE: The Complete Roman Empire Timeline: Dates of Battles, Emperors, and Events

Regardless of the fact that his father is widely considered to be one of the greatest Emperors the Roman Empire ever saw, Commodus reportedly exhibited signs of cruelty and capriciousness as a child. In one anecdote, he apparently ordered one of his servants to be thrown in the fire for failing to properly heat his bath to the right temperature.

Commodus in Power

Like many Roman emperors on this list, he also seemed to show a lack of care or consideration for the administration of the Roman state, instead preferring to fight in gladiatorial shows and chariot races. This left him at the whim of his confidants and advisors, who manipulated him to eliminate any rivals or execute those with lavish riches that they wished to acquire.

He also began to increasingly suspect those around him of conspiracy, as various assassination attempts against him, were foiled. This included one by his sister Lucilla, who was later exiled, and her co-conspirators executed. Similar fates eventually awaited many of Commodus’s advisors, such as Cleander, who effectively took over control of the government.

Yet after several of them died or were murdered, Commodus began to take back control during the later years of his reign, after which he developed an obsession with himself as a divine ruler. He bedecked himself in golden embroidery, dressed as different gods, and even renamed the city of Rome after himself.

Finally, in late 192 AD, he was strangled to death by his wrestling partner, on the command of his wife and praetorian prefects who had grown tired of his recklessness and behavior, and afraid of his capricious paranoia.

Domitian (51-96 AD)

Like many of the Roman emperors on this list, modern historians tend to be a bit more forgiving and revisionist for figures like Domitian, who was severely rebuked by contemporaries after his death. According to them, he had carried out a series of indiscriminate executions of the senatorial class, aided and abetted by a sinister coterie of corrupt informers, known as “delators”.

Was Domitian Really So Bad?

According to the dictates of what made a good emperor, in line with senatorial accounts and their preferences, yes. This is because he made an effort to rule without the senate’s help or approval, moving the affairs of the state away from the senate house and into his own imperial palace. Unlike his father Vespasian and brother Titus who ruled before him, Domitian abandoned any pretension that he ruled by the senate’s grace and instead implemented a very authoritarian type of government, centered on himself.

After a failed rebellion in 92 AD, Domitian also reportedly carried out a campaign of executions against various senators, killing at least 20 by most accounts. Yet, outside of his treatment of the senate, Domitian seemed to rule remarkably well, with astute handling of the Roman economy, careful fortification of the empire’s borders, and scrupulous attention to the army and people.

Thus, while he seemed to have been favored by these sections of society, he was most definitely hated by the senate and aristocracy, who he seemed to despise as insignificant and unworthy of his time. On the 18th of September 96 AD, he was assassinated by a group of court officials, who apparently had been earmarked by the emperor for future execution.

Galba (3 BC-69 AD)

Turning away now from Roman emperors who were fundamentally evil, many of Rome’s worst emperors, were also those, like Galba, who were simply inept and completely unprepared for the role. Galba, like Vitellius mentioned above, was one of the four emperors who ruled or claimed to rule the Roman empire, in 69 AD. Shockingly, Galba only managed to hold onto power for 6 months, which, up to this point, was a remarkably short reign.

Why Was Galba So Unprepared and Considered One of the Worst Roman Emperors?

Coming to power after the eventually calamitous reign of Nero, Galba was the first emperor who was not officially part of the original “Julio-Claudian Dynasty” founded by the first emperor, Augustus. Before he was able to enact any laws then, his legitimacy as a ruler was already precarious. Combine this with the fact that Galba came to the throne at the age of 71, suffering from severe gout, as well as the fact that he was beset by rebellions immediately, which meant that the odds were really stacked against him.

However, his biggest flaw was the fact that he allowed himself to be bullied by a clique of advisors and praetorian prefects who pushed him towards certain actions that alienated most of society from him. This included his vast confiscation of Roman property, his disbanding of legions in Germany without pay, and his refusal to pay certain praetorian guards who had fought for his position, against an early rebellion.

It seemed that Galba thought the position of emperor itself, and the nominal backing of the senate, rather than the army, would secure his position. He was gravely mistaken, and after multiple legions to the north, in Gaul and Germany, refused to swear allegiance to him, he was killed by the praetorians who were supposed to protect him.

Honorius (384-423 AD)

Like Galba, Honorius’s relevance to this list lies in his complete ineptitude for the role of emperor. Although he was the son of the revered emperor Theodosius the Great, Honorius’s reign was marked by chaos and weakness, as the city of Rome was sacked for the first time in 800 years, by a marauding army of Visigoths. Whilst this in itself didn’t mark the end of the Roman Empire in the west, it certainly marked a low point that accelerated its eventual fall.

How Responsible Was Honorius for the Sack of Rome in 410 AD?

To be fair to Honorius, he was only 10 when he assumed full control over the western half of the empire, with his brother Arcadius as co-emperor in control of the eastern half. As such, he was guided through his rule by the military general and advisor Stilicho, who Honorius’s father Theodosius had favored. At this time the empire was beset by continuous rebellions and invasions of barbarian troops, most notably the Visigoths who, on a number of occasions plundered their way through Italy itself.

Stilicho had managed to repel them on a few occasions but had to settle with buying them off, with a massive amount of gold (draining the region of its wealth). When Arcadius died in the east, Stilicho insisted that he should go to shore up affairs and oversee the accession of Honorius’s younger brother Theodosius II.

After consenting, the isolated Honorius, who had moved his headquarters to Ravenna (after which every emperor lived there), was convinced by a minister called Olympus that Stilicho planned to betray him. Foolishly, Honorius listened and ordered the execution of Stilicho upon his return, as well as any of those who had been supported by him or close to him.

After this, Honorius’s policy towards the Visigoth threat was capricious and inconsistent, in one instant granting the barbarians promised grants of land and gold, in the next reneging on any agreements whatsoever. Fed up with such unpredictable interactions, the Visigoths finally sacked Rome in 410 AD, after it had been intermittently under siege for more than 2 years, all the while Honorius watched on, helpless, from Ravenna.

After the fall of the eternal city, Honorius’s reign was characterized by the steady erosion of the western half of the empire, as Britain became effectively separated, to fend for itself, and rebellions by rival usurpers left Gaul and Spain essentially out of central control. In 323, having seen over such an ignominious reign, Honorius died of enema.

READ MORE: The Fall of Rome: When, Why and How Did Rome Fall?

Should We Always Believe the Presentation of the Roman Emperors in the Ancient Sources?

In a word, no. Whilst an impressively colossal amount of work has been carried out (and still is) to ascertain the reliability and accuracy of ancient sources, the contemporary accounts we have are inevitably plagued by certain problems. These include:

- The fact that most of the literary sources we have were written by senatorial or equestrian aristocrats, who shared a natural inclination to criticize the actions of emperors that did not correspond with their interests. Emperors like Caligula, Nero, or Domitian who largely disregarded the concerns of the senate, will likely have had their vices exaggerated in the sources.

- There is a noticeable bias against emperors who have just passed away, whereas those who are living are rarely criticized (at least explicitly). The existence of certain histories/accounts over others can create a bias.

- The secretive nature of the emperor’s palace and court meant that rumor and hearsay proliferated and seem to often populate the sources.

- What we have is only an incomplete history, often with some large gaps missing in various sources/writers.

The fascinating policy of “damnatio memoriae” also meant that some emperors would be severely maligned in subsequent histories. This policy, which is detectable in the name, literally meant that a person’s memory was damned.

In reality, this meant that their statues were defaced, their names edged out of inscriptions and their reputation associated with vice and disrepute in any later accounts. Caligula, Nero, Vitellius, and Commodus all received damnatio memoriae (along with a large host of others).

Did the Office of the Emperor Naturally Corrupt?

For some individuals, like Caligula and Commodus, it seemed as though they already showed predilections for cruelty and avarice before taking up the throne. However, the absolute power that the office endowed somebody with, naturally had its corrupting influences that could corrupt even the worthiest of souls.

Moreover, it was a position that many surrounding the emperor would envy, as well as being one of extreme pressure to placate all the elements of society. Since people could not wait for, or depend on the elections of heads of state, they had to often take matters into their own hands, through more violent means.

As mentioned about some of these figures above, many of them were the targets of failed assassination attempts, which naturally made them more paranoid and ruthless in trying to root out their opponents. In the often-arbitrary executions and “witch-hunts” that would follow, many senators and aristocrats would fall victim, earning the ire of contemporary writers and speakers.

Add to this the recurrent pressures of invasion, rebellion, and rampant inflation, it’s no surprise that certain individuals committed terrible deeds with the immense power they possessed.