Flourishing more than 3,000 years ago (c. 1,000 BC to c. 300 BC), ancient Greece, thanks to its many contributions to human culture, was one of the most successful ancient civilizations in history. And it remains a model civilization even today.

However, the history of ancient Greece is not entirely rosy. While committed to intellectual and cultural development, the Greeks were also huge fans of war. Their most common enemy? Themselves!

In fact, the ancient Greeks were fighting each other so often that they never actually unified into one cohesive civilization until the final chapter of their ancient story.

All this fighting, over so many years, can make it tough to keep track of all the important events that took place throughout the history of ancient Greece.

This ancient Greece timeline, which starts with the pre-Myceneany period and ends with the Roman conquest, should make Greek history a bit easier to understand.

Table of Contents

Entire Ancient Greece Timeline: Pre-Mycenaean to the Roman Conquest

The Earliest Greeks (c. 9000 – c. 3000 BC)

The very earliest indications of human settlement in ancient Greece date back to before 7000 B.C.

These early ancient Greeks continued to grow and develop throughout the Bronze Age, slowly developing increasingly complex building structures, food economies, agriculture, and seafaring capabilities.

In the late Bronze Age, Crete and other Grecian islands were home to the Minoans, whose ornate palaces can still be seen in the ruins on the island of Crete to this day.

READ MORE: King Minos of Crete: The Father of The Minotaur

Mycenaean Period – (c. 3000-1000 BC)

The analogous ancient Greek civilization on the mainland was known as the Mycenaeans, who advanced to more complex levels of civilization with the development of carefully organized urban centers, early Greek architecture, unique styles of artwork, and a set writing system.

They also established some of the most prominent cities of Greece, both in the ancient world and some surviving to this day, including Athens and Thebes.

The Trojan War – (c. 1100 BC )

Toward the end of the Bronze Age and Mycenaean dominance, the Mycenaeans set out across the Mediterranean to lay siege to the great city of Troy, located on the northwest coast of modern Turkey.

The exact reasons for the war remain wreathed in myth and legend, told most famously in epic poems by Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Virgil, the Aeneid. However, truths are often contained within mythical narratives, and epic poems remain important resources both for the discerning historical knowledge of the era and as a study of great Greek literature.

The stories claim that Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite quarreled over a golden apple that was to be given “to the fairest.” The goddess brought the argument before the Greek god Zeus, the lord of all the gods.

READ MORE: 41 Greek Gods and Goddesses: Family Tree and Fun Facts

Not wishing to get involved, he sent them to a lonely young man, Paris, a prince of Troy, who presented the apple to Aphrodite after she promised him the most beautiful woman in the world.

Unfortunately, the most beautiful woman was already married, to King Menelaus of Mycenaean Sparta. Helen ran away with Paris back to Troy, but Menelaus called in his Greek allies and pursued them, kicking off the Trojan War.

The Trojan War raged for ten years according to Homer, until one day the Greeks on the shoreline disappeared. All that remained was a large wooden horse. Despite the wise counsel to leave it, the Trojans thought the horse to be the spoils of war, so they brought the horse into the city. In the night, the Greeks hidden within the horse crept out and opened the gates of Troy to their waiting comrades, ending the Trojan War in a bloody, brutal sack of the city.

Although historians have been trying for centuries to determine the actual historical events that inspired these stories, the truth continues to elude. Nevertheless, it’s through this myth and others that later Greeks, those from the Classical period, saw their pasts and themselves, contributing in part to ancient Greece’s rise to power.

The Fall of Mycenae – (c. 1000 BC)

The Mycenaean civilization disappeared toward the end of the Bronze Age, leading to Greece’s “Dark Age,” but the collapse of Mycenae remains an intriguing mystery to this day.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: 16 Oldest Known Cultures From Around The World

Because many other civilizations across southern Europe and western Asia also experienced a decline during this period, many theories have been advanced to explain this “Bronze Age Collapse,”, from invasions by the “sea peoples” or neighboring Dorians (who later settled on the Peloponnese and became the Spartans) to complex internal dissension that leads to widespread civil wars and the fall of a unified kingdom.

However, historians and archaeologists have yet to find conclusive support for any one theory, and the question remains hotly debated to this day why human societies in this region during this time period entered into a period of such slow progress. Nonetheless, life went on.

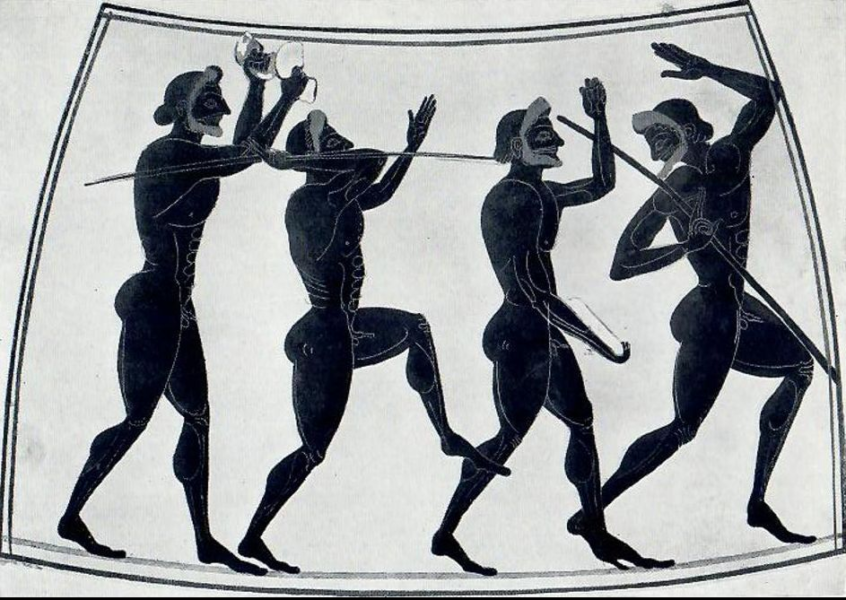

The First Recorded Olympic Games – (776 BC)

One thing that happened during this period, just before the start of the Archaic Period in Greece, was that a new tradition was recorded: the Olympic Games. Though believed to have been in existence for as many as 500 years before, the Olympic games held in the city-state of Elis in 776 B.C. are the first officially recorded instance discovered to date.

READ MORE: The 12 Olympian Gods and Goddesses

The Archaic Period – (650-480 BC)

The next period on the Ancient Greece timeline is the Archaic Period. During this era, the ancient Greek city-states we know – Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, etc. – rose to prominence and set the stage for the Classical period, the most famous from ancient Greek history.

Messenian Wars – (743 – 464 BC)

Although referred to as the First, Second, and Third Messenian Wars, in reality, the only proper war was that of the First Messenian War, fought between Sparta and Messenia.

Following the Spartan victory, Messenia (the region to the west of Sparta on the Peloponnese, mainland Greece’s southernmost peninsula) was largely dismantled and its inhabitants scattered or enslaved. The Second and Third Messenian Wars were each uprisings launched by the oppressed Messenians against the Spartans, and in both cases, the Spartans triumphed decisively.

This allowed Sparta to take full control over the Peloponnese, and using the Messenians as helots (slaves) gave the city-state the power it needed to rise to the top of the ancient Greek world.

Draconian Laws are Established in Athens – (621 BC)

Greece’s Draconian laws still exert influence in the modern world, both in vernacular and, much more deeply, in the understanding of a need for written law codes. The laws were written by Draco, the first recorded legislator of Athens, in response to unjust rulings made from vague oral laws.

The need for written law was certainly true, but the laws Draco outlined imposed severe and even brutal penalties for almost any level of infraction, to such a degree that popular legend even claims that the laws were not written in ink, but in blood. To this day, calling a law “Draconian” is labeling it as unfairly severe.

Democracy is Born in Athens – (510 BC)

With the assistance of the Spartans, the Athenians managed to overthrow their king in 510 B.C. The Spartans hoped to set up a puppet ruler in his stead, but an Athenian named Cleisthenes wrestled influence away from the Spartans and established the basic structure of Athens’ very first democracy, which would only grow, solidify, and develop in the following century.

READ MORE: Who Invented Democracy? The True History Behind Democracy

The Persian Wars – (492–449 BC)

Although they had engaged in little to no direct combat, the Greek city-states and the great Persian Empire were set on an inevitable collision course. The great Persian Empire controlled large swathes of territory, and now her gaze landed on the Greek peninsula.

The Ionian Revolt – (499-493 BC)

The strongest spark of the Persian Wars came with the Ionian Revolt. A group of Greek colonies in Asia Minor wished to rebel against Persian rule. Unsurprisingly Athens, the forerunners of democracy, sent soldiers to aid the uprising. In a raid on Sardis, an accidental fire began that engulfed much of the ancient city.

READ MORE: The Satraps of Ancient Persia: The Guardians of the Realm

King Darius vowed revenge against the ancient Greeks, and in particular the Athenians. After a particularly brutal massacre of Athens’ allied city state Etruria, even after the Etrurians had surrendered, the Athenians knew they would be shown no mercy.

The First Persian War – (490 BC)

The Persian King Darius I made his first advancements by intimidating Macedonia in the far north into a diplomatic capitulation. Too terrified of the great Persian war machine, the king of Macedon allowed his nation to become a vassal state of Persia, something the other Greek city-states remembered with bitterness well into the reign of Philip II and even that of his son Alexander the Great, some 150 years later.

The Battle of Marathon – (490 BC)

Athens sent their best runner, Pheidippides, to plead for assistance from Sparta. After running the distance of 220 kilometers over rough terrain in only two days, he was distraught to have to make the return run with news that Sparta could not aid them. It was the time of a Spartan celebration of the Greek god Apollo and they were forbidden from engaging in warfare for another ten days. Pheidippides’ desperate journey is the origin of the modern marathon, the name taken from the battlefield of the ancient world.

Now knowing they were alone, the Athenian army marched out of the city to meet the vastly superior Persian army which had landed at the Bay of Marathon. Though initially on the defensive, after five days of a stalemate, the Athenians unexpectedly launched a wild attack on the Persian army and, much to everyone’s surprise, broke the Persian line. The Persians retreated from Greek shores, though it wouldn’t be long before they returned. Despite a Greek victory at the Battle of Marathon, The Persian Wars were far from over.

The Second Persian War (480-479 BC)

Darius I would never get the chance to return to the shores of ancient Greece, but his son, Xerxes I, took up his father’s cause and mustered a massive invasion force to march on Greece. There is a story that as Xerxes watched his tremendous army cross the Hellespont into Europe, he shed tears thinking of the terrible bloodshed that awaited the ancient Greeks at the hands of his men.

The Battle of Thermopylae – (480 BC)

Thermopylae may be the best-known event of the Ancient Greece Timeline, popularized as it is by biceps and abs in the movie 300. The cinematic version is – very loosely – based on the true battle. Although three hundred Spartan warriors formed the vanguard of the Greek forces at the Battle of Thermopylae, they were actually joined by around 7,000 allied Greek warriors, though the entire force was still vastly outnumbered by the invading Persians.

The group never hoped to win, but instead planned to delay the advancing Persians in the bottleneck mountain pass at Thermopylae. They held out for seven days, three of which involved heavy fighting until they were betrayed by a local who showed the Persians a route around the pass.

The Spartan king Leonidas sent most of the other Greek soldiers away, and together the 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians that remained fought to the death, giving their lives to allow time for the other city-states of ancient Greece to prepare their defense.

The Sack of Athens – (480 BC)

Despite the heroic sacrifice of the Spartans and Thespians, when Persia came through the pass heading south, the Greek forces knew they could not stop the Persian juggernaut in open battle. Instead, they evacuated the entire city of Athens. The Persians arrived to find the city empty, but they still burned the Acropolis in revenge for Sardis.

Victory at Salamis – (480 BC)

With their city in flames, the highly skilled Athenian navy rallied to lead the other city-states in the battle against the Persian fleet. Lured into the tight waterways surrounding the city of Salamis, the overwhelming numbers of the Persian fleet proved useless, as they were unable to maneuver properly to engage. The smaller, quicker Greek ships encircling them caused havoc and the Persian ships eventually broke and fled.

Following the defeat at Salamis, Xerxes withdrew the majority of his forces back to Persia, leaving only a token force under the command of his top general. This Persian detachment was finally defeated the following year at the Battle of Plataea.

Classical Period of Ancient Greece (480-336 BC)

The Classical Period is the one that we most picture when anyone mentions Ancient Greece – the great temple of the goddess Athena perched atop the acropolis of Athens, the greatest of Greek philosophers roaming the streets, Athens’ literature, theatre, wealth, and power all at their absolute peak. Yet many do not realize how comparatively short-lived the Classical Period was when stacked up against other eras in ancient Greek history. In under two centuries, Athens would reach the heights of its Golden Age and then come crashing down, never to truly rise in power again in ancient times.

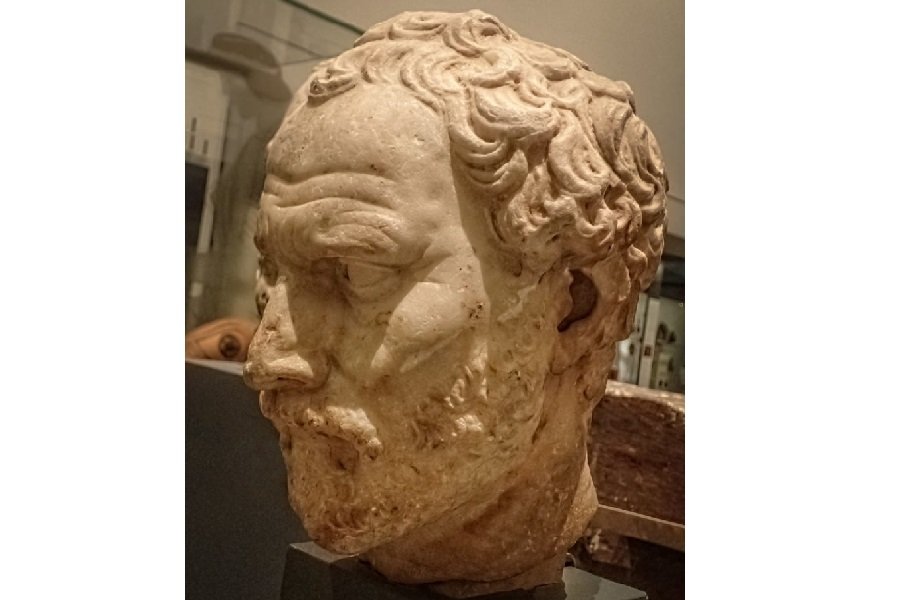

During the Classical Period, the world was introduced to a whole new way of thinking. The philosophy of the Classical Period held three of history’s most well-known philosophers – Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Known as the Socratic philosophers and each one beginning as a student of the one that came before, these three men created the basis for all western philosophy to come and heavily influenced the evolution of modern western thought.

Though many divergent schools of thought would arise, including the four main post-Socratic philosophies – Cynicism, Skepticism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism – none of it would be possible without the three Socratic forefathers.

In addition to thinking a lot about a lot of different things, the Greeks of the Classical Period were also busy expanding their influence around the rest of the ancient world.

The Delian League and Athenian Empire- (478 – 405 BC)

In the aftermath of the Persian Wars, Athens emerged as one of the most powerful of Greek cities, despite its losses and damage at the hands of the Persians. Led by the famous Athenian statesman, Pericles, Athens used the fear of further Persian invasion to establish the Delian League, a group of allied Greek city-states intended to unite the peninsula in defense.

The league initially met and kept their joint treasury on the island of Delos. However, Athens slowly began to amass greater power, and abuse its power within the league, moving the treasury to the city of Athens itself and drawing from it in support of Athens alone. Alarmed at the growing power of Athens, the Spartans decided it was time for some intervention.

Peloponnesian War (431-405 BC)

Sparta headed up their own confederation of Greek cities, the Peloponnesian League, and the conflict between the two Leagues, mainly focused on the two powerhouse cities in charge, became known as the Peloponnesian War. The Peloponnesian War spanned twenty-five years and was the only direct conflict between Athens and Sparta in history.

In the earliest stages of the war, Athens dominated, using its naval supremacy to cruise the coastline of ancient Greece and quell unrest.

However, after a disastrous invasion attempt against the Greek city-state of Syracuse in Sicily which left the Athenian fleet in shambles, their strength began to waver. With support from their former enemy, the Persian Empire, Sparta was able to support several cities in rebellions against Athens, and finally utterly decimate the fleet at Aegospotami, the final battle of the Peloponnesian Wars.

The loss of the Peloponnesian Wars left Athens a shell of its former glory, with Sparta arising as the single most powerful city in the ancient Greek world. The conflict did not end with the end of the Peloponnesian Wars, however. Athens and Sparta never reconciled and remained in frequent battles up until their defeat at the hands of Philip II.

The Rise of Macedonia (382 – 323 BC)

The northernmost region of Ancient Greece, known as Macedonia, was something of a black sheep to the rest of ancient Greek civilization. While many Greek city-states embraced and proclaimed democracy, Macedonia remained stubbornly a monarchy.

The other city-states also considered the Macedonians to be uncouth, uncultured offshoots – the rednecks of ancient Greece if you will – and had never forgiven Macedonia for their perceived cowardly capitulation to Persia.

Macedonia struggled under the weight of constant raids from neighboring states, a pitiful citizen militia unable to combat them, and rising debts. However, ancient Greece was soon to see that it had greatly underestimated Macedonia thanks to the arrival of Philip II.

The Reign of Philip II – (382-336 BC)

Philip II became king of Macedonia almost by accident. Though he was far down on the line of succession, a series of unfortunate deaths placed a young child in line for the throne just as Macedonia faced several exterior threats. The Macedonian noblemen quickly placed Philip on the throne instead, yet they still had little hope that he could do more than ensure the limping survival of the nation.

But Philip II was a serious and intelligent young man. He had studied military tactics under some of the greatest generals of Thebes and he was cunning and ambitious. Upon becoming king, Philip quickly neutralized the surrounding threats through diplomacy, deception, and bribery as necessary, buying himself about a year of peace.

At that time he utilized the natural resources at his command, created a commissioned armed force, and trained them into one of the most effective fighting forces in the ancient world at that time. He emerged at the end of his year of training and swept through Greece, quickly conquering the entire peninsula. By the time of his unexpected assassination in 336 B.C., all of ancient Greece was under Macedonian control.

The Rise of Alexander the Great – (356-323 BC)

Philip’s son Alexander was just like his father in many ways, tough, ambitious, and highly intelligent. In fact, he was tutored as a child by the great Greek philosopher, Aristotle. Despite some early resistance in Greece, he quickly quashed any thoughts of uprisings by the Greek city-states and took on his father’s plans to invade Persia.

With the fearsome army developed by his father and a brilliant military mind, Alexander the Great surprised the world by taking on and defeating the feared Persian Empire, as well as conquering Egypt and parts of India.

READ MORE: Ancient Egypt Timeline: Predynastic Period Until the Persian Conquest

He was planning his invasion of the Arabian Peninsula when he contracted a serious illness. He died in Babylon in the summer of 323 B.C. He had become king at the age of 20 and died having conquered most of the known world by the time he was just 32 years old. Before his death, he ordered the construction of the Great Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Hellenistic Period – (323-30 BC)

Alexander the Great’s death threw ancient Greece and, thanks to Alexander’s conquests, most of the Mediterranean, into what is now known as the Hellenistic Period. Alexander died with no children and no clear heir, and though his top generals initially tried to preserve his kingdom, they soon split and fell into disputes and battles for control for the following four decades, known as the Wars of the Diadochi.

Eventually, four main Hellenistic Empires emerged; the Ptolemaic Empire of Egypt, the Antigonid Empire in classical ancient Greece and Macedonia, the Seleucid Empire of Babylon and the surrounding regions, and the Kingdom of Pergamon based largely out of the region of Thrace.

Roman Conquest of Ancient Greece (192 BC – 30 BC)

Throughout the Hellenistic Period, the four kingdoms remained the top powers of the Mediterranean, despite being frequently at odds with one another and near constant political intrigue and betrayal within their own royal families – all except Pergamon, which somehow enjoyed healthy family dynamics and peaceful transfers of power throughout its existence. In later years, Pergamon made the wise choice of allying closely with the rapidly expanding Roman Republic.

The Fall of the Hellenistic Kingdoms – (192-133 BC)

Once a small, insignificant little state, the fierce, warlike Romans had amassed power, territory, and a reputation after their triumph over Carthage in the First and Second Punic Wars. In 192 B.C., Antiochus III launched an invasion of Greek territory, but Rome intervened and soundly defeated the Seleucid forces. The Seleucid Empire never fully recovered and struggled until falling to Armenia.

The Antigonid Empire of Greece fell to Rome after the Macedonian Wars. After a long, mutually successful friendship with Rome, Attalus III of Pergamon died without an heir, and instead willed his entire kingdom to the Roman Republic, leaving only Ptolemaic Egypt surviving.

READ MORE: Roman Wars

An End to Ptolemaic Egypt – (48-30 BC)

Though deeply in debt, Ptolemaic Egypt managed to hold on as a significant power longer than the other three Hellenistic states. However, it also fell to Rome after two serious diplomatic missteps. On October 2nd, 48 B.C., Julius Caesar arrived on Egyptian shores in pursuit of Pompey the Great, who he had recently defeated at the battle of Pharsalus.

Hoping to curry favor with Caesar, the young king Ptolemy XII ordered Pompey murdered on his arrival and presented Caesar with Pompey’s head. Caesar was horrified, and easily accepted overtures from Ptolemy’s sister, Cleopatra. He defeated Ptolemy XII and established Cleopatra as queen.

After Caesar’s murder, Cleopatra enjoyed an alliance and affair with Mark Antony. Yet relations between Antony and Caesar’s nephew Octavian were strained. When the tenuous alliance disintegrated and war broke out, Cleopatra supported her lover with Egyptian forces, and eventually, both Antony and Cleopatra lost to Octavian and his top general, Agrippa, in a naval battle at Actium.

They fled back to Egypt, pursued by Octavian, and Cleopatra made one last desperate attempt to ingratiate herself with Octavian upon his arrival. He was unmoved by her advances, and she and Antony both committed suicide, and Egypt fell under Roman control, ending the Hellenistic Period and the dominance of ancient Greece in the Mediterranean world.

Ancient Greece Timeline Ends: Greece Joins the Roman Empire

Octavian returned to Rome and established himself, through careful political maneuvering, as ostensibly the first Emperor of Rome, thus beginning the Roman Empire, which would become one of the largest and greatest nations throughout history. Although the era of Greece ostensibly ended with the creation of the Roman Empire, the ancient Romans held the Greeks in high esteem, preserving and spreading many aspects of Greek culture throughout their empire, and ensuring that many survived to this day.