Egypt was one of the first and most successful of the ancient kingdoms. Several dynasties ruled Egypt from different parts of the Nile, helping dramatically reshape the history of civilization and the western world. This Ancient Egypt timeline walks you through the entire history of this great civilization.

Table of Contents

Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 B.C.)

Ancient Egypt had been inhabited by nomadic peoples for hundreds of thousands of years before the first inklings of Egyptian civilization began to appear. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of human settlement back to around 300,000 B.C., but it wasn’t until nearer 6000 B.C. that the first signs of permanent settlements begin to appear around the Nile Valley.

The earliest Egyptian history remains vague – details gleaned from pieces of art and accouterments left in early burial chambers. During this period, hunting and gathering remained important factors of life, despite the beginnings of agriculture and animal husbandry.

Towards the end of this period, the first indications arise of diverging social statuses, with some tombs containing more lavish personal items and a clearer distinction in means. This social differentiation was the first movement toward a consolidation of power and the rise of Egyptian dynasties.

Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100-2686 B.C.)

Though early Egyptian villages remained under autonomous rule for many centuries, the social differentiation led to the rise of individual leaders and the first kings of Egypt. A common language, though likely with deep dialectical differences, allowed for continued unification that resulted in a two-way division between Upper and Lower Egypt. It was also about this time that the first Hieroglyphic writing began to appear.

The historian Manetho named Menes as the legendary first king of a united Egypt, though earliest written records name Hor-Aha as the king of the First Dynasty. The historical record remains unclear, with some believing that Hor-Aha was simply a different name for Menes and the two are the same individual, and others considering him to be the second Pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period.

The same may be true of Narmer, who is claimed to have peacefully united the Upper and Lower Kingdoms, yet his may also be another name or title for the first Pharaoh of a united Egypt. The Early Dynastic Period encompassed two dynasties of Egypt and ended with the reign of Khasekhemwy, leading into the Old Kingdom period of Egyptian history.

Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2181 B.C)

The son of Khasekhemwy, Djoser, kicked off the Third Dynasty of Egypt and also the period known as the Old Kingdom, one of the greatest in Egyptian history and the era of much of the iconic Egyptian symbolism most associated with ancient Egypt to this day. Djoser commissioned the first pyramid in Egypt, the Step Pyramid, to be built in Saqqara, the necropolis just north of the great city of Memphis, the capital of the Old Kingdom.

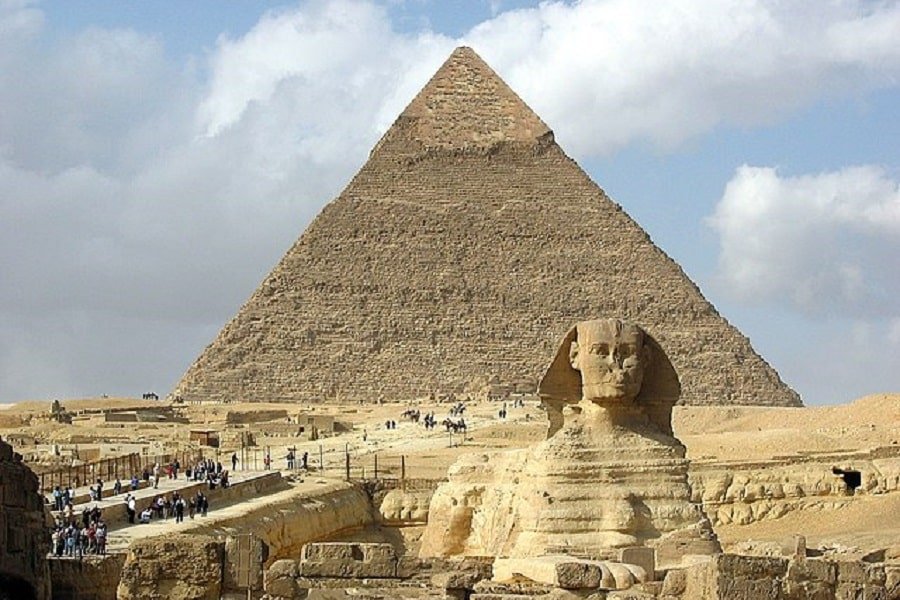

The Great Pyramids

The height of the pyramid building took place under the rule of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt. The first Pharaoh, Sneferu, built three large pyramids, his son, Khufu (2589–2566 BC), was responsible for the iconic Great Pyramid of Giza, and Khufu’s sons oversaw the construction of the second pyramid in Giza and the Great Sphinx.

Although written records during the Old Kingdom period remain limited, engravings on steles surrounding the pyramids and cities provide some details regarding the names and accomplishments of the Pharaohs, and the utterly unprecedented architectural construction during the period is, in itself, evidence of a strong central government and flourishing bureaucratic system. The same strength of rule led to some incursions up the Nile into the Nubian territory and expanding interest in trade for more exotic goods such as ebony, incense, and gold.

The Fall of the Old Kingdom

Centralized power weakened during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt as priests began to amass greater power through their oversight over funerary practices. Regional priests and governors began to hold more sway over their territories. The additional strain came in the form of a great drought. which prevented the flooding of the Nile and created widespread famine which the Egyptian government could do nothing to minimize or alleviate. By the end of the reign of Pepi II, questions regarding the proper line of succession eventually led to civil war in Egypt and the collapse of the centralized Old Kingdom government.

First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2030)

Egypt’s First Intermediate Period is a confusing time, seeming to encompass both a fair amount of political turmoil and strife and also an expansion of available goods and wealth that would have benefited those of lower status. However, historical records are severely limited in this period, so it is difficult to gain a strong sense of life during the era. With the distribution of power to more local monarchs, these rulers looked after the interests of their own regions.

The lack of a centralized government meant that no great works of art or architecture were built to provide historical details, yet the distributed power also brought greater production of goods and availability. Ancient Egyptians who previously could not afford tombs and funerary texts suddenly could. It is likely that life was somewhat improved for the average Egyptian citizen.

However, later texts from the Middle Kingdom such as The Admonitions of Ipuwer, which largely reads as a noble lamenting the rise of the poor, also states that: “pestilence is throughout the land, blood is everywhere, death is not lacking, and the mummy-cloth speaks even before one comes near it,” suggesting that there was still a certain amount of chaos and danger during the time.

The Progression of Government

The supposed heirs of the Old Kingdom did not simply disappear during this time. Successors still claimed to be the rightful 7th and 8th Dynasties of Egypt, ruling from Memphis, yet the complete lack of information regarding their names or deeds historically speaks volumes as to their actual power and effectiveness. The 9th and 10th dynasty kings left Memphis and established themselves in Lower Egypt in the city of Herakleopolis. Meanwhile, around 2125 B.C., a local monarch of the city of Thebes in Upper Egypt named Intef challenged the power of the traditional kings and led to a second split between Upper and Lower Egypt.

Over the following decades, the monarchs of Thebes claimed rightful rule over Egypt and began building a strong central government once again, expanding into the territory of the kings of Herakleopolis. The First Intermediate Period came to an end when Mentuhotep II of Thebes successfully conquered Herakleopolis and reunited Egypt under a single rule in 2055 B.C., beginning the period known as the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom (c. 2030-1650)

The Middle Kingdom of Egyptian civilization was a strong one for the nation, though lacking some of the specific defining characteristics of the Old Kingdom and the New Kingdom: those being their pyramids and later the empire of Egypt. Yet the Middle Kingdom, encompassing the reigns of the 11th, and 12th dynasties, was a Golden Age of wealth, artistic explosion, and successful military campaigns that continued to propel Egypt forward in history as one of the most enduring states of the ancient world.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: 16 Oldest Known Cultures From Around The World

Although the local Egyptian nomarchs maintained some of their higher levels of power into the Middle Kingdom era, a single Egyptian Pharaoh once again held ultimate power. Egypt stabilized and flourished under the kings of the 11th Dynasty, sending a trade expedition to Punt and several exploratory incursions south into Nubia. This stronger Egypt persisted into the 12th Dynasty, whose kings conquered and occupied northern Nubia with the help of the first standing Egyptian army. Evidence suggests military expeditions into Syria and the Middle East in this period as well.

READ MORE: Ancient Egyptian Weapons: Spears, Bows, Axes, and More!

Despite the rising power of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom, it seems similar events to the fall of the Old Kingdom once again plagued the Egyptian monarchy. A drought period led to a wavering of trust in the central Egyptian government and the long life and reign of Amenemhet III lead to fewer candidates for succession.

His son, Amenemhet IV, successfully took power, but left no children and was succeeded by his possible sister and wife, though their full relationship is unknown, Sobekneferu, the first confirmed female ruler of Egypt. However, Sobekneferu also died with no heirs, leaving the way open for competing ruling interests and a fall into another period of governmental instability.

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 – 1570 B.C.)

Although a 13th Dynasty did rise into the vacancy created by the death of Sobekneferu, ruling from the new capital of Itjtawy, built by Amenemhat I in the 12th Dynasty, the weakened government could not hold strong centralized power.

A group of Hykos people who had immigrated to northeastern Egypt from Asia Minor split off and created the Hykos 14th Dynasty, ruling the northern portion of Egypt out of the city of Avaris. The subsequent 15th Dynasty maintained power in that area, in opposition to the 16th Dynasty of native Egyptian rulers based out of the southern city of Thebes in Upper Egypt.

The tension and frequent conflicts between the Hykos kings and the Egyptian kings characterized much of the strife and instability that marked the Second Intermediate Period, with victories and losses on both sides.

New Kingdom (c. 1570 – 1069 B.C.)

The New Kingdom period of Ancient Egyptian civilization, also known as the Egyptian Empire period, began under the reign of Ahmose I, the first king of the 18th dynasty, who brought the Second Intermediate Period to a close with his expulsion of the Hykos kings from Egypt. The New Kingdom is the portion of Egyptian history best known to the modern day, with most of the most famous Pharaohs ruling during this period. In part, this is due to a rise in historical records, as a rise in literacy throughout Egypt allowed for more written documentation of the period, and rising interactions between Egypt and neighboring lands similarly increased historical information available.

Establishing a New Ruling Dynasty

After removing the Hykos rulers, Ahmose I took many steps politically to prevent a similar incursion in the future, buffering the lands between Egypt and neighboring states by expanding into nearby territories. He pushed the Egyptian military into regions of Syria and also continued strong incursions south into Nubian-held regions. By the end of his reign, he had successfully stabilized Egypt’s government and left a strong position of leadership to his son.

The successive Pharaohs include Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, and Thutmose II, and Hatshepsut, perhaps the best-known native Egyptian Queen of Egypt, as well as Akhenaten and Ramses. All continued the military and expansion efforts modeled by Ahmose and brought Egypt to its greatest height of power and influence under Egyptian rule.

A Monotheistic Shift

By the time of the rule of Amenhotep III, the priests of Egypt, particularly those of the cult of Amun, had once again begun to grow in power and influence, in a similar chain of events as those that led to the fall of the Old Kingdom, Perhaps all too aware of this history, or perhaps just resenting and distrusting of the drain on his power, Amenhotep III sought to elevate the worship of another Egyptian god, Aten, and thereby weaken the power of the Amun priests.

The tactic was taken to extremes by Amenhotep’s son, originally known as Amenhotep IV and married to Nefertiti, he changed his name to Akhenaten after he declared Aten the only god, the official religion of Egypt, and banished worship of the other old pagan gods. Historians are not certain whether Akhenaten religious policies came from true pious devotion to Aten or continued attempts to politically undermine the priests of Amun. Regardless, the latter was successful, but the extreme shift was poorly received.

After the death of Akhenaten, his son, Tutankhaten, immediately reversed his father’s decision, changed his name to Tutankhamun, and restored the worship of all the gods as well as the prominence of Amun, stabilizing a rapidly degenerating situation.

The Beloved Pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty

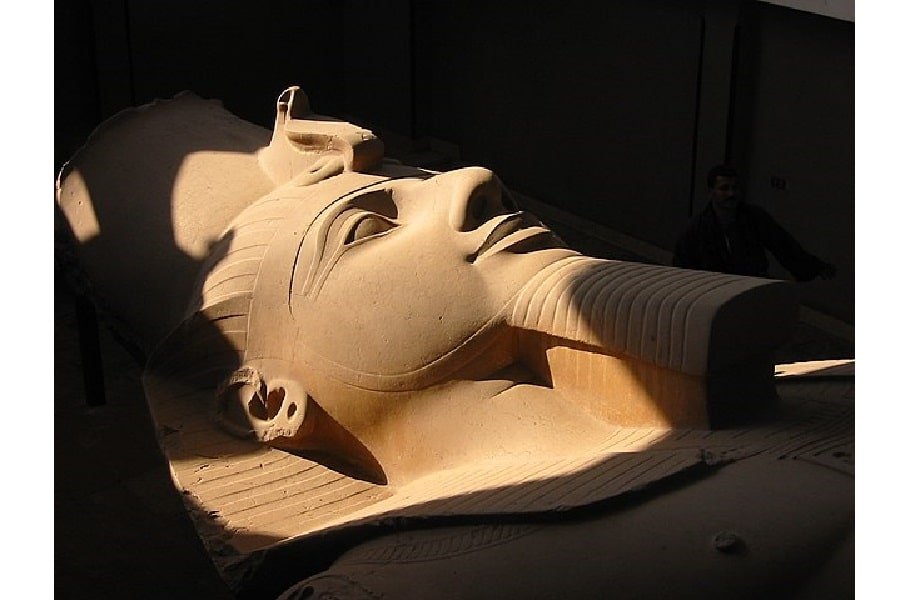

One of the most famous and long-lived rulers of Egypt was the great Ramses II, long associated with the Biblical story of the migration of the Jewish people out of Egypt, though historical records indicate he is likely not that Pharaoh. Ramses II was a powerful king and the Egyptian state thrived under his rule. After his defeat of the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh, he became the author and signatory of the world’s first written peace treaty.

Ramses lived to the incredible age of 96 and had been Pharaoh for so long that his death temporarily caused a mild panic in ancient Egypt. Few could remember a time when Ramses II wasn’t the king of Egypt, and they feared governmental collapse. However, Ramses’ oldest surviving son, Merenptah, who was actually his thirteenth born, successfully took over as Pharaoh and continued the reign of the 19th dynasty.

Fall of the New Kingdom

The 20th Dynasty of ancient Egypt, with the exception of the stronger rule of Ramses III, saw a slow decline in the power of the Pharaohs, once more repeating the course of the past. As the priests of Amun continued to amass wealth, land, and influence, the power of the kings of Egypt slowly waned. Eventually, rule once again split between two factions, the priests of Amun declaring rule from Thebes and the traditionally descended Pharaohs of the 20th dynasty attempting to maintain power from Avaris.

Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070-664 B.C.)

The collapse of a unified Egypt that led into the Third Intermediate Period was the beginning of the end of native rule in Ancient Egypt. Taking advantage of the division of power, the Nubian kingdom to the south marched down the Nile River, retaking all of the lands they had lost to Egypt in previous eras and eventually taking power over Egypt itself, with the 25th ruling Dynasty of Egypt being made up of Nubian kings.

The Nubian rule over ancient Egypt fell apart with the invasion of the war-like Assyrians in 664 B.C., who sacked Thebes and Memphis and established the 26th Dynasty as client kings. They would be the last native kings to rule Egypt and managed to reunite and oversee a few decades of peace before being confronted with even greater power than Assyria, which would bring an end to the Third Intermediate Period and to Egypt as an independent state for centuries to come.

Late Period of Egypt and the End of the Ancient Egypt Timeline

With power greatly diminished, Egypt was a prime target for invading nations. To the east in Asia Minor, Cyrus the Great had the Achaemenid Persian Empire had been consistently rising in power under the succession of numerous strong kings and expanding their territory throughout Asia Minor. Eventually, Persia set its sights on Egypt.

Once conquered by the Persians, Ancient Egypt would never again be independent. After the Persians came the Greeks, led by Alexander the Great. After this historic conqueror died, his empire was divided up, launching the Ptolemaic period of ancient Egypt, which lasted until the Romans conquered Egypt in the late stages of the first century BC. Thus ends the Ancient Egypt timeline.

READ MORE: Ancient Greece Timeline

READ MORE: Roman Empire Timeline