Japanese Mythology, in its broadest sense, is a pastiche of different traditions and myths, derived mainly from Shintoism and Japanese Buddhism. Both provide Japanese Mythology with a pantheon of elaborate and varied deities, guardians, and “kami” – holy spirits and forces associated with the natural world and its features.

Additionally, more localized Japanese folklore constitutes an important component of this rich synthesis of belief as well.

Embedded within this loose framework is also a deep reverence and veneration of the dead – not only the heroic figures in Japanese history and myth but also each family’s ancestral dead as well (who themselves become Kami). As such, it is a vibrant area of study and curiosity that still retains a central role in contemporary culture across the Japanese archipelago.

Table of Contents

The History of Shinto and Japanese Buddhism in Japan

Whilst today, Shinto and Buddhism are seen to be two distinct sets of beliefs and doctrines, for much of Japan’s recorded history they were practiced side-by-side throughout Japanese society.

Indeed, before the mandated state adoption of Shinto as the official religion of Japan in 1868, “Shinbutsu-konkō” was instead the only organized religion – which was a syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism, with the name meaning a “jumbling up of kami and buddhas”.

The two religions are therefore quite deeply entwined and have borrowed much from each other to generate their current forms. Even many temples in Japan have both Buddhist and Shinto shrines connected to each other, as they have been for centuries.

The Differences between Shinto and Japanese Buddhism

Before delving deeper into some of the specific myths, figures, and traditions that make up Japanese Mythology, it is important to further trace the integral elements of Shinto and Japanese Buddhism, to explore briefly what does actually set them apart.

Shinto, unlike Buddhism, originated in Japan and is considered its indigenous national religion, with the largest number of active adherents and followers on the islands.

Buddhism on the other hand is widely considered to have originated from India, although Japanese Buddhism has many uniquely Japanese components and practices, with many “Old” and “New” schools of Buddhism being indigenous to Japan. Its form of Buddhism is also quite closely linked to Chinese, and Korean Buddhism, although again, it has many of its own unique elements.

READ MORE: 15 Chinese Gods from Ancient Chinese Religion: The Eight Immortals, Dragon Gods, and More!

Japanese Buddhist Approaches to Mythology

Whilst Buddhists do not generally revere a god, or gods in the traditional sense, they do honor and praise the Buddhas (enlightened ones), Bodhisattvas (those on the path towards Buddhahood), and Deva of Buddhist tradition, who are spiritual beings that guard over people (similar in ways to angels).

READ MORE: The 19 Most Important Buddhist Gods

However, Japanese Buddhism is notable for its pronounced interpretation of these figures as part of an actual pantheon of divine beings – more than 3,000 of them.

Shinto Approaches to Mythology

Shintoism – as a polytheistic religion – similarly has a large pantheon of gods, like the Pagan Pantheon of Ancient Greek Gods and Roman Gods. In fact, the Japanese pantheon is said to contain “eight million kami”, although this number is really supposed to connote the infinite number of kami that watch over the Japanese islands.

Furthermore, “Shinto” loosely means “way of the Gods” and is intrinsically embedded in the natural and geographical features of Japan itself, including its mountains, rivers, and springs – indeed, the kami are in everything. They are present in all of the natural world and its phenomena, being similar to both Daoism and Animism.

However, there are also a number of major, overarching Kami in the Shinto tradition, just as there is a hierarchy and pre-eminence of certain divine beings in Japanese Buddhism, some of which will be explored further below. Whilst many of them take on the appearance of creatures and hybrids, it is also the case that many Kami, Bodhisattvas, or Devas, look remarkably human as well.

Major Practices and Beliefs of Japanese Mythology

Both Shintoism and Japanese Buddhism are very old religious outlooks and whilst they may contain a vast collection of different deities and practices, each possesses certain key elements that help to constitute a coherent system of belief.

Shinto Practices and Beliefs

For Shinto, it is essential for adherents to honor the kami at shrines, whether in the household (called kamidana), at ancestral sites, or at public shrines (called jinja). Priests, called Kannushi, oversee these public sites and the proper offerings of food and drink, as well as the ceremonies and festivals, carried out there, such as the traditional kagura dances.

This is done to ensure harmony between the kami and society, which together have to strike a careful balance. Whilst most Kami are considered friendly and amenable to the people around them, there are also malevolent and antagonistic kami as well who can carry out destructive action against a community. Even typically kinder ones can as well if their warnings are not heeded – an act of retribution called shinbatsu.

Since there are so many local and ancestral manifestations of kami, there are accordingly more intimate levels of interaction and association for different communities. The kami of a particular community is known as their ujigami, whilst the even more intimate kami of a particular household is known as the shikigami.

What is consistent, however, throughout each of these varying levels of intimacy, is the integral element of purification and cleansing associated with most interactions between humans and Kami.

Practices and Beliefs of Japanese Buddhism

Japanese Buddhism has its most prominent links to “Gods” and mythology in “Esoteric” versions of Buddhism, such as Shingon Buddhism, which was developed by the Japanese monk Kukai in the 9th century AD. It shares its inspiration from a form of Vajrayana Buddhism originating in India and taken up further in China as “The Esoteric School”.

With Kukai’s teaching and the spread of Esoteric forms of Buddhism came many new deities to Japan’s Buddhist belief system, which Kukai had discovered from his time spent studying and learning about the Esoteric School in China. It became instantly very popular, especially for its ritualistic nature and the fact that it began to borrow many deities from Shinto Mythology.

READ MORE: The History of Buddhism

Besides the pilgrimage to Mount Kōya which is a prominent practice for Shingon adherents, the Goma fire ceremony has a central place in Japanese Buddhism practices, with a strong mythological element as well.

The ritual itself, carried out daily by qualified priests and “archayas”, consists of igniting and tending a “consecrated fire” in the Shingon temples, which is supposed to have a cleansing and purifying effect for whomever the ceremony is directed towards – be it, the local community, or the whole of mankind.

Watching over these ceremonies is the Buddhist deity Acala, known as the “immovable one” – a wrathful deity, supposed to be a remover of obstacles and destroyer of evil thoughts. In carrying out the ceremony then, where the fire can often reach a few meters in height and is accompanied sometimes by the banging of taiko drums, the deities’ favor is invoked to ward away detrimental thoughts and grant communal wishes.

Festivals

It would be remiss not to mention the vibrant and vivacious festivals that contribute so much to Japanese Mythology and the way it is still encountered in Japanese society today. In particular, the Shinto-oriented festival Gion Matsuri and the Buddhist festival Omitzutori are both very consistent with the central themes of Japanese mythology because of their cleansing and purifying elements.

Whilst the Gion Matsuri festival is directed towards the appeasement of the Kami, to ward off earthquakes and other natural disasters, the Omitzuri is supposed to cleanse people of their sins.

In the former, there is a rich explosion of Japanese culture with a massive variety of different shows and performances, whilst the latter is a slightly more tranquil affair with water-washing the lighting of a huge fire, which is supposed to rain down auspicious embers on the observance, to guarantee their good fortune in life.

Major Myths in Japanese Mythology

Just as the practice is integral to the broader area of Japanese Mythology, it is essential that these practices are imbued with meaning and context. For many of them, this is derived from the myths that are widely known throughout Japan, giving not only its mythological framework greater substance but helping to embody essential aspects of the nation itself.

Key Sources

The rich tapestry of Japanese Mythology derives its constituent components from a large variety of different sources, including oral tradition, literary texts, and archaeological remains.

Whilst the patchwork nature of Japan’s countryside communities meant that localized myths and traditions proliferated, often independent of each other, the increasing emergence of a centralized state over the country’s history meant that an overarching tradition of myth also spread across the archipelago.

Two literary sources stand out as canonical texts for the centralized spread of Japanese Mythology – the “Kojiki,” the “Tale of Old Age,” and “Nihonshoki,” the “Chronicle of Japanese History.” These two texts, written in the 8th century CE under the Yamato state, provide an overview of the cosmogony and mythical origins of the Japanese islands and the people that populate them.

The Creation Myths

The creation myth of Japan is recounted through both the Kamiumi (birth of the gods) and the Kuniumi (birth of the land), with the latter coming after the former. In the Kojiki, the primordial deities known as the Kotoamatsukami (“separate heavenly deities”) created the heavens and the earth, although the earth at this stage was just a formless mass drifting in space.

These initial deities did not reproduce and possessed no gender or sex. However, the deities that came after them – the Kamiyonanayo (“the Seven Divine Generations”) – consisted of five couples and two lone deities. It is from the last of these two couples, Izanagi and Izanami, who were both brother and sister (and man and wife), that the rest of the Gods were born, and the earth was shaped into a solid form.

After their failure to conceive their first child – due to improper observance of a ritual – they ensured they adhered strictly to the protocols passed down to them from the older deities thereafter. As a result, they were then able to produce a lot of divine children, many of which became the Ōyashima – the eight great islands of Japan – Oki, Tsukushi, Iki, Sado, Yamato, Iyo, Tsushima, and Awaji.

The Birth and Death of Kagutsuchi

The last of the earthly gods to be born from Izagani and Izanami was Kagutsuchi – the fire god, whose birth burnt the genitals of his mother Izanami, killing her in the process!

For this act Izanagi killed his son, decapitating him and cutting his body into eight pieces, which themselves became eight volcanoes (and Kami) on the Japanese archipelago. When Izanagi then went to search for his wife in the world of the dead, he saw that out of her rotting corpse, she had birthed the eight Shinto gods of thunder.

READ MORE: Japanese God of Death Shinigami: The Grim Reaper of Japan

Having seen this, Izanagi then returned to the land of the living in Tachibana no Ono in Japan and carried out the purification ceremony (misogi) which is so central to Shinto rituals. During the process of stripping himself for the misogi, his garments, and accessories became twelve new Gods, followed by another twelve as he proceeded to cleanse the different parts of his body. The last three, Amaterasu Omikami, Tsukuyomi-no-mikoto, and Takehaya-susano’o-no-mikoto, are the three most important and will be discussed more below.

Tengu

Whilst it is quite difficult to distinguish any Buddhist Japanese myths, from Buddhism more generally, Tengu are certainly an example of Japan’s own addition to the subject, as mischievous figures deriving from Japanese folk religion. Typically pictured as an imp, or taking the form of birds of prey or a monkey, the Tengu are supposed to live in the mountainous regions of Japan and were originally considered no more than harmless pests.

However, in Japanese Buddhist thought, they are considered harbingers or acolytes of evil forces such as the demon Mara, who is thought to distract Buddhist monks away from their pursuit of enlightenment. Furthermore, in the Heian period, they were seen as the source of various epidemics, natural disasters, and violent conflicts.

Japanese Myths from Folk Mythology

Whilst the doctrines and beliefs of Shinto and Buddhism both provide so much for the broader subject of Japanese mythology, it is important to note that there is also a rich and colorful collection of Japanese folklore that is still widely known across the archipelago. Some, like “The Hare of Ibana”, or the Legend of Japan’s first emperor Jimmu are related to the creation stories enmeshed in the history of Japan.

Others, such as the tale of Momotarō or Urashima Tarō recount elaborate fairy tales and legends, full of talking animals and malevolent demons. Furthermore, many of them contain social commentary on various elements of Japanese society or tell ghost stories of vengeful spirits such as the “snow woman”, Yuki-Onna. Many of them also provide a moral story, encouraging the listener to adopt virtuous traits.

Major Gods of Japanese Mythology

Whilst many would protest at the term “God” for either Buddhist or Shinto deities, it is a useful term of reference to create some understanding for people used to interpreting divine figures as such. Furthermore, they exhibit many of the characteristics of more familiar gods from Ancient Western mythology.

Amaterasu

When discussing the Japanese deities in more detail, it is appropriate to start with the highest deity in the Shinto Pantheon – Amaterasu Omikani (“the great divinity illuminating heaven”). She was born from Izanagi’s cleansing ritual described above and thereafter became the Sun Goddess for all of Japan. It is also from her that the Japanese imperial family is supposed to derive.

She is also the ruler of the spiritual plain Takama no Hara where the Kami reside and has many prominent temples throughout the Japanese islands, with the most important being the Ise Grand Shrine in the Mie Prefecture.

There are also many important myths that surround the story of Amaterasu, which often involve her tempestuous relationships with other gods. For example, her split from Tsukuyomi is given as the reason that night and day are divided, just as Ameratsu provides humanity with agriculture and sericulture out of the same mythological episode.

Tsukuyomi

Tsukuyomi is closely related to the sun goddess Amaterasu and another of the most important Shinto gods who was born from Izanagi’s cleansing ritual. He is the Moon God in Shinto mythology and although he and Amaterasu seem to be close initially, they become detached permanently (personifying the split of night and day) because Tsukuyomi killed the Shinto God of food Ukemochi.

This happened when Tsukuyomi came down from heaven to dine with Ukemochi, attending the banquet on Amaterasu’s behalf. Because of the fact that Ukemochi gathered up the food from diverse locations and then spewed up the food for Tsukuyomi, he killed Ukemochi in disgust. It was therefore on account of Tsukuyomi’s rashness that he was banished from Amaterasu’s side.

Susanoo

Susanoo is the younger brother of the sun goddess Amaterasu, similarly born from his father’s cleansing misogi. He is a contradictory god, sometimes conceptualized as a god related to sea and storms, whilst sometimes being the provider of harvests and agriculture. In Japanese Buddhism however, he takes on a more consistently negative aspect, as a god linked to pestilence and disease.

READ MORE: Water Gods and Sea Gods From Around the World

In various myths in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Susanoo is expelled from the heavens for his bad behavior. After this, however, he is also portrayed as a cultural hero, slaying monsters and saving Japan from destruction.

Later ethnologists and historians have seen him as a figure embodying the antagonistic aspects of existence, juxtaposed against Amaterasu and her husband Tsukuyomi. Indeed they argue further that he represents the rebellious and antagonist elements of society more broadly, in contradistinction from the imperial state (derived from Amaterasu), which was supposed to bring harmony to society.

Fūjin

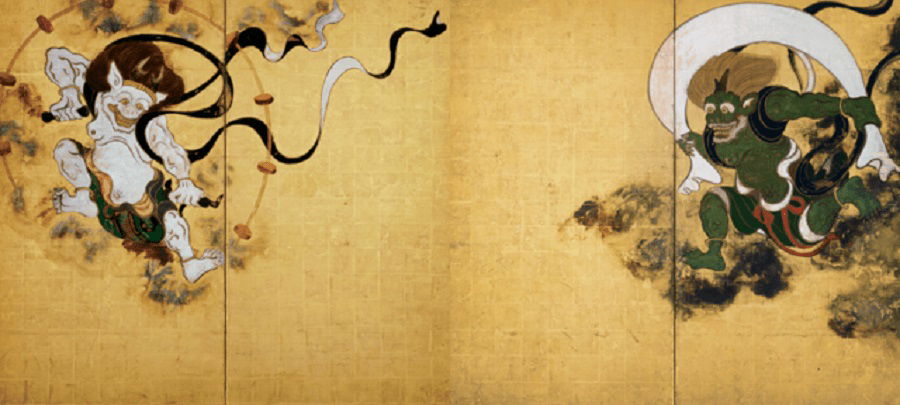

Fūjin is a Japanese god with a long history in both Shinto and Japanese Buddhism. He is the God of wind and is usually portrayed as a green ghoulish wizard, carrying a bag of wind above his head or around his shoulders. He was born from Izanami’s corpse in the underworld and was of the only gods to escape back into the world of the living, along with his brother Raijin (who he is often depicted with).

READ MORE: 10 Gods of Death and the Underworld From Around the World

Raijin

As previously mentioned, Raijin is the brother of Fūjin but is himself the God of lightning, thunder and storms, just like Thor from the Norse pantheon. Like his brother, he takes on a very menacing appearance and tends to be accompanied by Taiko drums (which he beats to make the sound of thunder), and dark clouds. His statues litter the Japanese islands and he is a central deity to placate if one wants to travel between them free of storms!

Kannon

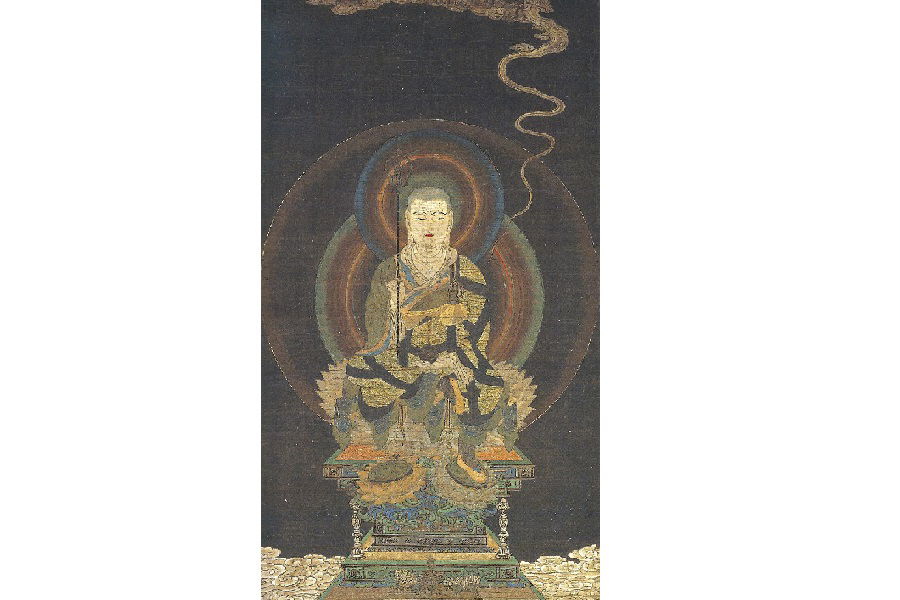

Kannon is a bodhisattva in Japanese Buddhism (one on the path to enlightenment and becoming Buddha) and is also one of the most commonly portrayed Buddhist deities in Japan. Often draped in flowers, Kannon is a deity of Mercy in Japanese mythology, with one thousand arms, and eleven faces. Whilst usually depicted as an anthropomorphic figure, there is also a “horse-Kannon” variant!

Jizo Bosatsu

Jizo Bosatsu is the Buddhist deity of children and travelers in Japanese mythology, with many “Jizo” statues littering Japanese forest trails and groves. He is also a guardian spirit of deceased children and in a synthesis of folk and Buddhist tradition, small stone towers are often placed nearby Jizo statues.

The reason for this is the belief that children who die before their parents in Japanese society are not able to properly enter the afterlife but instead must build these stone towers so that their parents one day can. It is therefore seen as an act of kindness for a traveler who comes across a Jizo statue to help the spirits in this endeavor.

The Presence of Mythology in Modern Japan

After the Second World War, there was a marked decrease in Japanese religious life and practice, as elements of the nation began to secularize and had a certain “crisis of identity”. Out of this vacuum, “New Religions” (Ellwood & Pilgrim, 2016: 50) emerged, which were often more practical and materialistic adaptations of Shintoism or Japanese Buddhism (such as Soka Gakkai).

However, much still remains of Ancient Japanese myth and its associations in Modern Japan, as many of the new religious movements hearken back to traditional myths and customs for inspiration.

Indeed, Japan still shares a deep appreciation of the natural world and possesses more than 100,000 Shinto shrines and 80,000 Buddhist shrines, each littered with mythological statues and figurines. At the Ise Grand Shrine, discussed above, there is a festival every 25 years to honor the Sun Goddess Amaterasu and the other kami who have nearby shrines. The myth still very much lives on.