Ancient Sparta is one of the most well-known cities in Classical Greece. The Spartan society was known for its highly-skilled warriors, elitist administrators, and its reverence for stoicism, people today still look to the Spartans as model citizens in an idealist ancient society.

Yet, as is often the case, many of the perceptions we have of classical Sparta are based on over-glorified and exaggerated stories. But it was still an important part of the ancient world that is worth studying and understanding.

However, while the city state of Sparta was a significant player both in Greece and the rest of the ancient world starting in the mid 7th century BCE, Sparta’s story ends abruptly. Stress on the population resulting from strict citizenship requirements and an over-dependence on slave labor combined with pressure from other powers in the Greek world proved to be too much for the Spartans.

And while the city never fell to a foreign invader, it was a shell of its former self by the time the Romans entered the scene in the 2nd century BCE. It is still inhabited today, but the Greek city of Sparta has never regained its ancient glory.

Fortunately for us, the Greeks began using a common language sometime in the 8th century BCE, and this has provided us with a number of primary sources which we can use to uncover the ancient history of the city of Sparta.

To help you understand more about the history of Sparta, we have used some of these primary sources, along with a collection of important secondary sources, to reconstruct the story of Sparta from its founding until its fall.

Table of Contents

Where is Sparta?

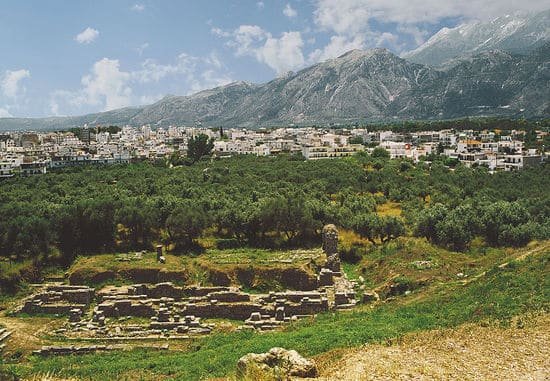

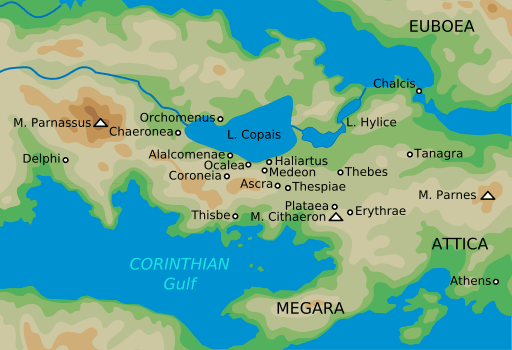

Sparta in located in the region of Laconia, referred to in ancient times as Lacedaemon, which makes up most of the southwestern Peloponnese, the largest and southernmost peninsula of the Greek mainland.

It is bordered by the Taygetos Mountains to the west and the Parnon Mountains the east, and while Sparta was not a coastal Greek city, but it was just 40 km (25 miles) north of the Mediterranean Sea. This location made Sparta into a defensive stronghold.

The difficult terrain surrounding it would have made it difficult if not impossible for invaders, and because Sparta was located in a valley, intruders would have been spotted quickly.

ulrichstill [CC BY-SA 2.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en)]

However, perhaps more importantly, the city state Sparta was built on the banks of the Eurotas River, which runs down from the highlands of the Peloponnese and empties into the Mediterranean.

The ancient Greek city was built alongside the eastern banks of the river, helping to provide an additional line of defense, but the modern-day city of Sparta is found to the west of the river.

In addition to serving as a natural boundary, the river also made the region surrounding the city of Sparta one of the most fertile and agriculturally productive. This helped Sparta prosper into one of the most successful Greek city states.

Map of Ancient Sparta

Here is a map of Sparta as it relates to the relevant geographical points in the region:

Ancient Sparta at a Glance

Before delving into the ancient history of the city of Sparta, here is a snapshot of the important events in Spartan history:

- 950-900 BCE – The four original villages, Limnai, Kynosoura, Meso, and Pitana, come together to form the polis (city state) of Sparta

- 743-725 BCE – The First Messenian War gives Sparta control over large portions of the Peloponnese

- 670 BCE – The Spartans are victorious in the second Messenian War, giving them control over the entire region of Messenia and giving them hegemony over the Peloponnese

- 600 BCE – the Spartans lend support to the city state of Corinth, forming an alliance with their powerful neighbor that would eventually morph into the Peloponnesian League, a major source of power for Sparta.

- 499 BCE – The Ionian Greeks revolt against Persian rule, starting the Greco-Persian War

- 480 BCE – the Spartans lead the Greek force at the Battle of Thermopylae, which leads to the death of one of Sparta’s two kings, Leonidas I, but helps Sparta earn the reputation of having the strongest military in ancient Greece.

- 479 BCE- the Spartans lead the Greek force at the Battle of Plataea and win a decisive victory over the Persians, ending the Second Persian Invasion of ancient Greece.

- 471-446 BCE – City states of Athens and Sparta fight several battles and skirmishes alongside their allies in a conflict that is now known as the First Peloponnesian War. It ended with the signing of the “Thirty Years’ Peace,” but tensions remained.

- 431-404 BCE – Sparta faces up against Athens in The Peloponnesian War and emerges victorious, bringing an end to the Athenian Empire and giving birth to the Spartan Empire and Spartan hegemony.

- 395-387 BCE – The Corinthian War threatened Spartan hegemony, but peace terms brokered by the Persians left Sparta as the leader of the Greek World

- 379 BCE – War breaks out between the city states of Sparta and Thebes, known as the Theban or Boeotian War

- 371 BCE – Sparta loses the Battle of Leuctra to Thebes, which ends the Spartan empire and marks the beginning of the end of classical Sparta

- 260 BCE – Sparta helps Rome in The Punic Wars, helping it maintain relevant despite a shift in power away from ancient Greece and toward Rome

- .215 BCE – Lycurgus from the Eurypontid line of kings overthrows his Agiad counterpart, Agesipolis III, bringing an end to the dual-king system that had existed without interruption since the founding of Sparta.

- 192 BCE – The Romans overthrow the Spartan monarch, ending Spartan political autonomy and relegating Sparta to the annals of history.

Spartan History Before Ancient Sparta

The story of Sparta typically begins in the 8th or 9th century B.C with the founding of the city of Sparta and the emergence of a unified Greek language. However, people had been living in the area where Sparta would be founded starting in the Neolithic Era, which dates back some 6,000 years.

It is believed civilization came to the Peloponnese with the Mycenaean, a Greek culture that rose to dominance alongside the Egyptians and the Hittites during the 2nd millennium BCE.

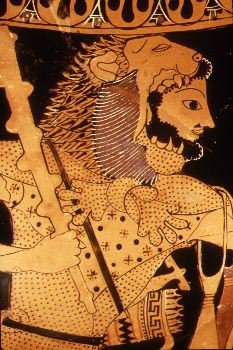

National Archaeological Museum [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

Based on the extravagant buildings and palaces they built, the Mycenaeans are believed to have been a very prosperous culture, and they laid the foundation for a common Greek identity which would serve as a basis for the ancient history of Greece.

For example, the Odyssey and the Iliad, which were written in the 8th century BCE, were based on wars and conflicts fought during Mycenaean times, specifically the Trojan War, and they played an important role in creating a common culture amongst the divided Greeks, even though their historical accuracy has been called into question and they have been deemed pieces of literature, not historical accounts.

However, by the 12th century BCE, civilization across all of Europe and Asia was descending into collapse. A combination of climatic factors, political turmoil, and foreign invaders from tribes referred to as Sea People, brought life to a halt for some 300 years.

There are few historical records from this time, and archaeological evidence also indicates a significant slowdown, leading this period to be referred to as the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

However, shortly after the beginning of the final millennium BCE, civilization once again began to flourish, and the city of Sparta was to play a pivotal role in the ancient history of the region and the world.

The Dorian Invasion

In ancient times, the Greeks were divided into four subgroups: Dorian, Ionian, Achaean, and Aeolian. All spoke Greek, but each had its own dialect, which was the primary means of distinguishing each one.

They shared many cultural and linguistic norms, but tensions between the groups were typically high, and alliances were often formed on the basis of ethnicity.

During Mycenaean times, the Achaeans were the most likely the dominant group. Whether or not they existed alongside other ethnic groups, or if these other groups remained outside Mycenaean influence, is unclear, but we do know that after the fall of the Mycenaeans and the Late Bronze Age Collapse, the Dorians, became the most dominant ethnicity on the Peloponnese. The city of Sparta was founded by Dorians, and they worked to construct a myth that credited this demographic change with an orchestrated invasion of the Peloponnese by Dorians from the north of Greece, the region where it is believed the Doric dialect first developed.

However, most historians doubt whether this is the case. Some theories suggest the Dorians were nomadic pastoralists who gradually made their way south as the land changed and resource needs shifted, whereas others believe the Dorians had always existed in the Peloponnese but were oppressed by the ruling Achaeans. In this theory, the Dorians rose to prominence taking advantage of turmoil amongst the Achaean-led Mycenaeans. But again, there is not enough evidence to fully prove or disprove this theory, yet no one can deny that Dorian influence in the region greatly intensified during the early centuries of the last millennium BCE, and these Dorian roots would help set the stage for the founding of the city of Sparta and the development of a highly-militaristic culture that would eventually become a major player in the ancient world.

The Founding of Sparta

We do not have an exact date for the founding of the city state of Sparta, but most historians place it sometime around 950-900 BCE. It was founded by the Dorian tribes living in the region, but interestingly, Sparta came into existence not as a new city but rather as an agreement between four villages in the Eurotas Valley, Limnai, Kynosoura, Meso, and Pitana, to merge into one entity and combine forces. Later on, the village of Amyclae, which was located a bit further away, became part of Sparta.

This decision gave birth to the city state of Sparta, and it laid the foundation for one of the world’s greatest civilizations. It also is one of the main reasons why Sparta was forever governed by two kings, something that made it rather unique at the time.

Latest Ancient History Articles

Incan Gods and Goddesses: 14 Ancient Deities of the Inca Pantheon

Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses: 34 Deities of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers

Ancient Gods and Goddesses from Cultures Around the World

The Beginning of Spartan History: Conquering the Peloponnese

Whether or not the Dorians who later founded Sparta truly came from northern Greece as part of an invasion or if they simply migrated for survival reasons, Dorian pastoralist culture is ingrained into the early moments of Spartan history. For example, the Dorians are believed to have had a strong military tradition, and this is often attributed to their need to secure land and resources needed to keep animals, something that would have required constant war with nearby cultures. To give you an idea of how important this was to early-Dorian culture, consider that the names of the first few recorded Spartan kings translate from Greek into: “Strong Everywhere, “(Eurysthenes), “Leader” (Agis), and “Heard Afar” (Eurypon). These names suggest that military strength and success was an important part of becoming a Spartan leader, a tradition that would continue on throughout Spartan history.

This also meant that the Dorians who eventually became Spartan citizens would have seen securing their new homeland, specifically Laconia, the region surrounding Sparta, from foreign invaders as a top priority, a need that would have been further intensified by the stunning fertility of the Eurotas River valley. As a result, Spartan leads began sending people out to the east of Sparta to settle the land in between it and Argos, another large, powerful city state on the Peloponnese. Those who were sent to populate this territory, known as “neighbors” were offered large tracts of land and protection in exchange for their loyalty to Sparta and their willingness to fight should an invader threaten Sparta.

Gepsimos [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Elsewhere in Laconia, Sparta demanded subjugation from the people living there. Those who resisted were dealt with by force, and most of the people who were not killed were made into slaves, known as helots in Sparta. These individuals were bonded laborers who eventually made up the bulk of Sparta’s workforce and military, but, as one would expect in a situation of slavery, they were denied many basic rights. This strategy of converting the people in Laconia into either “neighbors” or helots allowed Sparta to become the hegemon in Laconia by the middle of the 8th century BCE (c. 750 BCE).

The First Messenian War

However, despite securing Laconia, the Spartans were not done establishing their influence in the Peloponnese, and their next target was the Messenians, a culture that lived on the southwestern Peloponnese in the region of Messenia. Generally speaking, there are two reasons why the Spartans chose to conquer Messenia. First, population growth resulting from the fertile land of the Eurotas Valley meant that Sparta was growing too big and needed to expand, and second, Messenia was perhaps the only region in ancient Greece with land that was more fertile and productive than that in Laconia. Controlling it would have given Sparta a tremendous base of resources to use to not only grow itself but to also exert influence over the rest of the Greek world.

Furthermore, archaeological evidence suggests the Messenians at the time were far less advanced than Sparta, making them an easy target for Sparta, which at the time was one of the most developed cities in the ancient Greek world. Some records indicate Spartan leaders pointed to a long-standing rivalry between the two cultures, which may have existed considered most Spartan citizens were Dorian and the Messenians were Aeolians. However, this was probably not as important of a reason as the others mentioned, and it’s likely this distinction was made so as to help Spartan leaders gain popular support for a war with the people of Messenia.

Unfortunately, there is little reliable historical evidence to document the events of The First Messenian War, but it is believed to have taken place between c. 743-725 BCE. During this conflict, Sparta was unable to completely conquer all of Messenia, but significant portions of Messenian territory did come under Spartan control, and the Messenians who did not die in the war were turned into helots in service of Sparta. However, this decision to enslave the population meant that Spartan control in the region was loose at best. Revolts broke out frequently, and this is what eventually led to the next round of conflict between Sparta and Messenia.

The Second Messenian War

In c. 670 BCE, Sparta, perhaps as part of an attempt to expand its control in the Peloponnese, invaded territory controlled by Argos, a city state in northeastern Greece that had grown to be one of Sparta’s biggest rivals in the region. This resulted in the First Battle of Hysiae, which started a conflict between Argos and Sparta that would result in Sparta finally bringing all of Messenia under its control.

This happened because the Argives, in an attempt to undermine Spartan power, campaigned throughout Messenia to encourage a rebellion against Spartan rule. They did this by partnering with a man named Aristomenes, a former Messenian king who still had power and influence in the region. He was meant to attack the city of Deres with the support of the Argives, but he did so before his allies had the chance to arrive, which caused the battle to end without a conclusive result. However, thinking their fearless leader had won, the Messenian helots launched a full-scale revolt, and Aristomenes managed to lead a short campaign into Laconia. However, Sparta bribed Argive leaders to abandon their support, which all but eliminated the Messenian chances of success. Pushed out of Laconia, Aristomenes eventually retreated to Mt. Eira, where he remained for eleven years despite Sparta’s near-constant siege.

Sparta took control over the rest of Messenia following the defeat of Aristomenes at Mt. Eira. Those Messenians who had not been executed as a result of their insurrection were once again forced to become helots, ending the Second Messenian War and giving Sparta near total control over the southern half of the Peloponnese. But the instability brought on by their dependence on helots, as well as the realization that their neighbors would invade whenever they had the chance, helped show the Spartan citizens how important it would be for them to have a premier fighting force if they wished to remain free and independent in an increasingly competitive ancient world. From this point on, military tradition becomes front and center in Sparta, as will the concept of isolationism, which will help to write the next few hundred years of Spartan history.

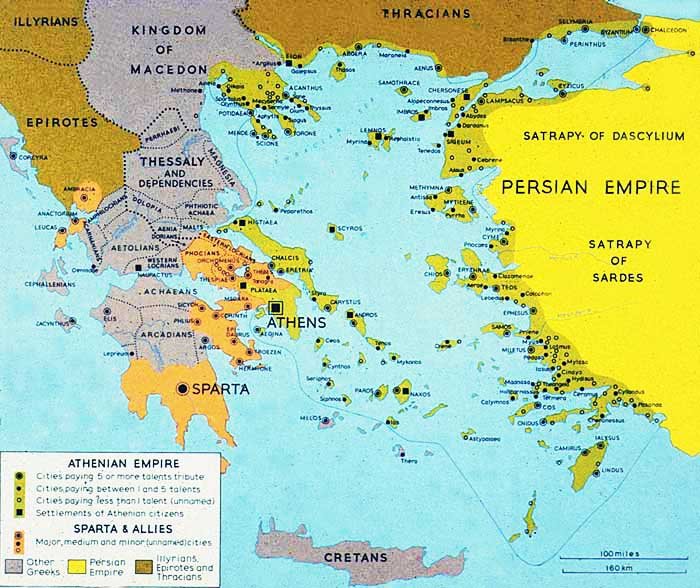

Sparta in the Greco-Persian Wars: Passive Members of an Alliance

With Messenia now fully under its control and an army that was quickly becoming the envy of the ancient world, Sparta, by the middle of the 7th century BCE, had become one of the most important population centers in ancient Greece and southern Europe. However, to the east of Greece, in modern-day Iran, a new world power was flexing its muscles. The Persians, who replaced the Assyrians as the Mesopotamian hegemon in the 7th century B.C, spent most of the 6th century BCE campaigning throughout western Asia and northern Africa and had built an empire that was at the time one of the largest in the entire world, and their presence would change the course of Spartan history forever.

The Formation of the Peloponnesian League

During this time of Persian expansion, ancient Greece had also risen in power, but in a different way. Instead of unifying into one large empire under the rule of a common monarch, independent Greek city-states flourished throughout the Greek mainland, the Aegean Sea, Macedon, Thrace, and Ionia, a region on the southern coast of modern-day Turkey. Trade amongst the various Greek city states helped ensure mutual prosperity, and alliances helped to establish a balance of power that kept the Greeks from fighting too much amongst themselves, although there were conflicts.

In the period between the Second Messenian War and the Greco-Persian Wars, Sparta was able to consolidate its power in Laconia and Messenia, as well as on the Peloponnese. It offered support to Corinth and Elis by helping remove a tyrant from the Corinthian throne, and this formed the basis of an alliance that would eventually be known as The Peloponnesian League, a loose, Spartan-led alliance between the various Greek city states on the Peloponnese that was intended to provide for mutual defense.

Ernst Wihelm Hildebrand [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Another important thing to consider about Sparta at this time is its growing rivalry with the city state of Athens. Although it’s true that Sparta helped Athens remove a tyrant and restore democracy, the two Greek city states were rapidly becoming the most powerful in the Greek world, and the outbreak of war with the Persians would further highlight their differences and eventually drive them to war, a series of events that defines Spartan and Greek history.

READ MORE: Who Invented Democracy? The True History Behind Democracy

The Ionian Revolt and the First Persian Invasion

The fall of Lydia (the kingdom that controlled much of modern-day Turkey up until the Persians invaded) in c. 650 BCE, meant the Greeks living in Ionia were now under Persian rule. Eager to exert their power in the region, the Persians moved quickly to abolish the political and cultural autonomy the Lydian kings had afforded the Ionian Greeks, creating animosity and making the Ionian Greeks difficult to rule.

This became obvious in the first decade of the 5th century B.C, a period known as the Ionian Revolt, which was put into motion by a man named Aristagoras. The leader of the city of Miletus, Aristagoras was originally a supporter of the Persians, and he tried to invade Naxos on their behalf. However, he failed, and knowing he would face punishment from the Persians, he called on his fellow Greeks to revolt against the Persians, which they did, and which the Athenians and the Eritreans, and to a lesser extent Spartan citizens, supported.

The region plummeted into turmoil, and Darius I had to campaign for nearly ten years to quell the insurrection. Yet when he did, he set out to punish the Greek city states who had helped the rebels. So, in 490 BCE, he invaded Greece. But after descending all the way to Attica, burning Eritrea on his way, he was defeated by the Athenian-led fleet at the Battle of Marathon, ending the First Persian Invasion of ancient Greece. However, the Greco-Persian Wars were just getting started, and soon the city state of Sparta would be thrown into the mix.

The Second Persian Invasion

Despite beating back the Persians more or less on their own at the Battle of Marathon, the Athenians knew that the war with Persia was not over and also that they would need help from the rest of the Greek world if they were to protect the Persians from succeeding in their attempt to conquer ancient Greece. This led to the first pan-Hellenic alliance in Greek history, but tensions within that alliance helped contribute to the growing conflict between Athens and Sparta, which ended in the Peloponnesian War, the largest civil war in Greek history.

The pan-Hellenic Alliance

Before the Persian King Darius I could launch a second invasion of Greece, he died, and his son, Xerxes, took over as the Persian sovereign in c. 486 BCE. Over the next six years, he consolidated his power and then set about preparing to finish what his father had started: the conquest of ancient Greece.

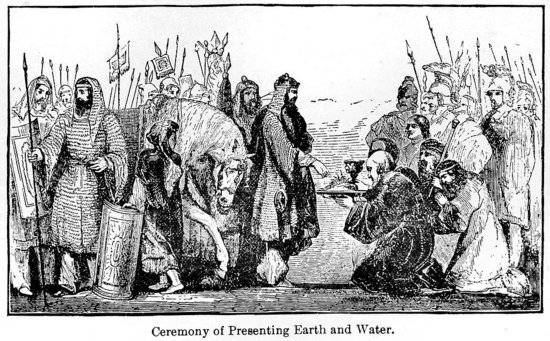

The preparations Xerxes undertook have gone down as the thing of legends. He amassed an army of nearly 180,000 men, a massive force for the time, and gather ships from all over the empire, mainly Egypt and Phoenicia, to build an equally impressive fleet. Furthermore, he built a pontoon bridge over the Hellespont, and he installed trading posts throughout Northern Greece that would make it considerably easier to supply and feed his army as it made the long march to the Greek mainland. Hearing of this massive force, many Greek cities responded to Xerxes’ tribute demands, meaning that much of ancient Greece in 480 BCE was controlled by the Persians. However, the larger, more powerful city states, such as Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, Argos, etc., refused, choosing instead to try to fight the Persians despite their massive numerical disadvantage.

The phrase earth and water is used to represent the demand of the Persians from the cities or people who surrendered to them.

Athens called all the remaining free Greeks together to devise a defense strategy, and they decided to fight the Persians at Thermopylae and Artemisium. These two locations were chosen because they provided the best topological conditions for neutralizing the superior Persian numbers. The narrow Pass of Thermopylae is guarded by the sea to one side and tall mountains to another, leaving a space of just 15m (~50ft) of passable territory. Here, only a small number of Persian soldiers could advance at one time, which leveled the playing field and increased the Greeks’ chances of success. Artemisium was chosen because its narrow straits gave the Greeks a similar advantage, and also because stopping the Persians at Artemisium would prevent them from advancing too far south towards the city state of Athens.

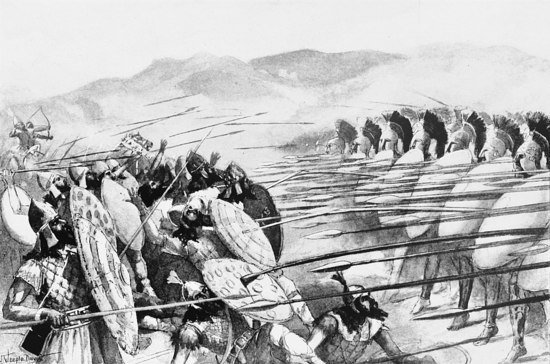

The Battle of Thermopylae

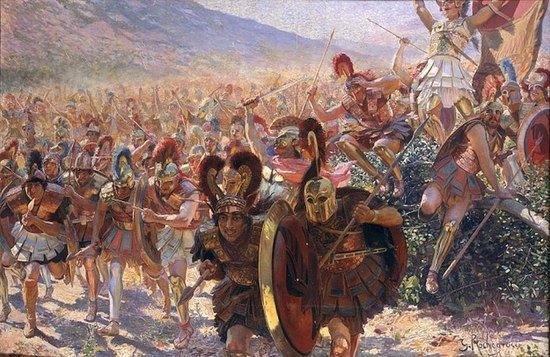

The Battle of Thermopylae took place in early August of 480 BCE, but because the city of Sparta was celebrating the Carneia, a religious festival held to celebrate Apollo Carneus, the chief deity of the Spartans, their oracles forbid them from going to war. However, responding to pleas from Athens and the rest of Greece, and also recognizing the consequences of inaction, the Spartan king at the time, Leonidas, amassed an “expeditionary force” of 300 Spartans. To join this force, you had to have a son of your own, for death was a near certainty. This decision angered the oracle, and many legends, specifically that around Leonidas’ death, has come from this part of the story.

These 300 Spartans were joined by a force of another 3,000 soldiers from around the Peloponnese, as around 1,000 from Thespiae and Phocis each, as well as another 1,000 from Thebes. This brought the total Greek force at Thermopylae to around 7,000, as compared to the Persians, who had around 180,000 men in their army. It’s true that the Spartan army had some of the best fighters in the ancient world, but the sheer size of the Persian army meant that likely wouldn’t matter.

The fighting took place over the course of three days. In the two days leading up to the outbreak of fighting, Xerxes waited, assuming the Greeks would disperse at the sight of his massive army. However, they did not, and Xerxes had no choice but to advance. On the first day of fighting, the Greeks, led by Leonidas and his 300, beat back wave after wave of Persian soldiers, including several attempts by Xerxes’ elite fighting force, the Immortals. On the second day, it was more of the same, giving hope to the idea that the Greeks might actually win. However, they were betrayed by a man from the nearby city Trachis who was looking to win favor with the Persians. He informed Xerxes of a backdoor route through the mountains that would allow his army to outflank the Greek force defending the pass.

Haring that Xerxes had learned of the alternate route around the pass, Leonidas sent most of the force under his command away, but he, along with his force of 300, as well as around 700 Thebans, chose to stay and serve as rearguard for the retreating force. They were eventually slaughtered, and Xerxes and his armies advanced. But the Greeks had managed to inflict heavy losses on the Persian army, (estimates indicate Persian casualties numbered around 50,000), but more importantly, they had learned their superior armor and weapons, combined with a geographical advantage, gave them a chance against the massive Persian army.

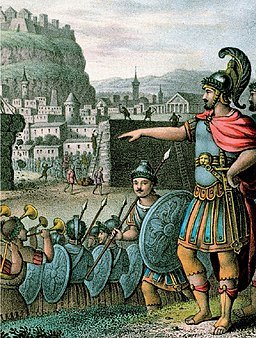

The Battle of Plataea

Despite the intrigue surrounding the Battle of Thermopylae, it was still a defeat for the Greeks, and as Xerxes marched south, he burned the cities that had defied him, including Athens. Realizing that their chances for survival were now slim if they continued to fight on their own, Athens pleaded with Sparta to take a more central role in the defense of Greece. Athenian leaders were furious at how few Spartan soldiers had been given to the cause, and at how willing Sparta seemed to be to let the other cities of Greece burn. Athens even went so far as to tell Sparta it would accept Xerxes’ peace terms and become a part of the Persian empire if they did not help, a move which caught the attention of Spartan leadership and moved them to assemble one of the largest armies in Spartan history.

In total, the Greek city states amassed an army of about 30,000 hoplites, 10,000 of whom were Spartan citizens. (the term used for the heavily armored Greek infantry), Sparta also brought some 35,000 helots to support the hoplites and also serve as light infantry. Estimates for the total number of troops the Greeks brought to the Battle of Plataea come in around 80,000, as compared to the 110,000.

After several days of skirmishing and attempting to cut the other off, the Battle of Platea began, and once again the Greeks stood strong, but this time they were able to drive back the Persians, routing them in the process. At the same time, possibly even on the same day, the Greeks sailed after the Persian fleet stationed on the island of Samos and engaged them at Mycale. Led by Spartan king Leochtydes, the Greeks achieved another decisive victory and crushed the Persian fleet. This meant that the Persians were on the run, and the second Persian invasion of Greece was over.

The Aftermath

After the Greek alliance had managed to beat back the advancing Persians, a debate ensued amongst the leaders of the various Greek city states. Leading one faction was Athens, and they wanted to continue to pursue the Persians in Asia so as to punish them for their aggression and also to expand their power. Some Greek city states agreed to this, and this new alliance became known as the Delian League, named for the island of Delos, where the alliance stored its money.

British Museum [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)]

Sparta, on the other hand, felt the purpose of the alliance was to defend Greece from the Persians, and since they had been driven from Greece, the alliance no longer served a purpose and could, therefore, be disbanded. During the final stages of the Second Persian Invasion of Greece during the Greco-Persian wars, Sparta had served as the Alliance’s de facto leader, largely because of its military superiority, but this decision to abandon the Alliance left Athens in charge, and they seized this opportunity to assume the position as the Greek hegemon, much to the dismay of Sparta.

Athens continued to wage war against the Persians until c. 450 BCE, and during these 30 years, it also considerably expanded its own sphere of influence, leading many scholars to use the term Athenian Empire instead of Delian League. In Sparta, which had always been proud of its own autonomy and isolationism, this growth in Athenian influence represented a threat, and their actions to fight against Athenian imperialism helped escalate tensions between the two sides and bring about the Peloponnesian War.

The Peloponnesian War: Athens vs Sparta

In the period following Sparta’s exit from the pan-Hellenic alliance until the outbreak of war with Athens, several major events took place:

- Tegea, an important Greek city state on the Peloponnese, revolted in c. 471 BCE, and Sparta was forced to fight a series of battles to quell this rebellion and restore Tegean loyalty.

- A massive earthquake struck the city state in c. 464 BCE, devastating the population

- Significant parts of the helot population revolted after the earthquake, which consumed the attention of Spartan citizens. They received help from the Athenians in this affair, but the Athenians were sent home, a move that caused tensions between the two sides to rise, and leading eventually to war.

The First Peloponnesian War

The Athenians did not like the way they had been treated by the Spartans after offering their support in the helot rebellion. They began to form alliances with other cities in Greece in preparation for what they feared was an imminent attack by the Spartans. However, in doing this, they escalated tensions even further.

In c. 460 BCE, Sparta sent troops to Doris, a city in northern Greece, to help them in a war against Phocis, a city allied at the time with Athens. In the end, the Spartan-backed Dorians were successful, but they were blocked by Athenian ships as they attempted to leave, forcing them to march overland. The two sides collided once again in Boeotia, the region to the north of Attica where Thebes is located. Here, Sparta lost the Battle of Tangara, which meant Athens was able to take control over much of Boeotia. The Spartans were defeated once again at Oeneophyta, which placed nearly all of Boeotia under Athenian control. Then, Athens to Chalcis, which gave them prime access to the Peloponnese.

Fearing the Athenians would advance on their territory, the Spartans sailed back to Boeotia and encouraged the people to revolt, which they did. Then, Sparta made a public declaration of the independence of Delphi, which was a direct rebuke to the Athenian hegemony that had been developing since the beginning of the Greco-Persian Wars. However, seeing the fighting was likely going nowhere, both sides agreed to a peace treaty, known as The Thirty Years’ Peace, in c. 446 BCE. It established a mechanism for maintaining peace. Specifically, the treaty stated that if there was a conflict between the two, either one had the right to demand it be settled over arbitration, and if this happened, the other would have to agree too. This stipulation effectively made Athens and Sparta equals, a move that would have angered both, particularly the Athenians, and it was a major reason why this peace treaty lasted far less than the 30 years for which it is named.

The Second Peloponnesian War

The First Peloponnesian War was more of a series of skirmishes and battles than an outright war. However, in 431 BCE, full-scale fighting would resume between Sparta and Athens, and it would last for nearly 30 years. This war, often referred to as simply The Peloponnesian War, played an important role in Spartan history as it led to the fall of Athens and the rise of the Spartan Empire, the last great age of Sparta.

The Peloponnesian War broke out when a Theban envoy in the city of Plataea to kill the Plataean leaders and install a new government was attacked by those loyal to the current ruling class. This unleashed chaos in Plataea, and both Athens and Sparta got involved. Sparta sent troops to support the overthrow of the government since they were allies with the Thebans. However, neither side was able to gain an advantage, and the Spartans left a force to lay siege to the city. Four years later, in 427 BCE, they finally broke through, but the war had changed considerably by then.

Plague had broken out in Athens due in part to the Athenian decision to abandon the land in Attica and open the city’s doors to any and all citizens loyal to Athens, causing overpopulation and propagating disease. This means that Sparta was free to ransack Attica, but their largely-helot armies never made it to the city of Athens since they were required to periodically return home to tend to their crops. Spartan citizens, who were consequently also the best soldiers due to the Spartan training program, were forbidden from doing manual labor, which meant the size of the Spartan army campaigning in Attica dependent on the time of year.

A Brief Period of Peace

Athens won a few surprising victories over the much more powerful Spartan army, the most significant of which was the Battle of Pylos in 425 BCE. This allowed Athens to establish a base and house the helots it had been encouraging to rebel, a move that was intended to weaken the Spartan’s ability to supply itself.

Museum of the Ancient Agora [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

In the years after the Battle of Pylos, it looked like Sparta may have fallen, but two things changed. First, the Spartans began offering helots more freedoms, a move that prevented them from rebelling and joining the ranks of the Athenians. But meanwhile, the Spartan general Brasidas began campaigning throughout the Aegean, distracting the Athenians and weakening their presence in the Peloponnese. While riding through the Northern Aegean, Brasidas managed to convince the Greek cities previously loyal to Athens to defect to the Spartans by speaking of the corrupt imperial ambitions of the Athenian-led city states of the Delian League. Fearing it would lose its stronghold in the Aegean, the Athenians sent their fleet to try and retake some of the cities that had spurned Athenian leadership. The two sides met in Amphipolis in 421 BCE, and the Spartans achieved a resounding victory, killing the Athenian general and political leader Cleon in the process.

This battle proved to both sides that the war was going nowhere, and so Sparta and Athens met to negotiate peace. The treaty was meant to last 50 years, and it made Sparta and Athens responsible for controlling their allies and preventing them from going to war and initiating conflict. This condition once again shows how Athens and Sparta were trying to find a way for both to coexist despite the massive power of each. But both Athens and Sparta were also required to give up the territories they had conquered in the early parts of the war. However, some of the cities that had pledged to Brasidas were able to achieve more autonomy than they had before, a concession for the Spartans. But despite these terms, the city state of Athens would continue to aggravate Sparta with its imperial ambitions, and Sparta’s allies, unhappy with the terms of peace, caused trouble that led to resumed fighting between the two sides.

Fighting Resumes

Fighting didn’t restart until c. 415 BCE. However, leading up to this year, a few important things happened. First, Corinth, one of Sparta’s closest allies, but a city that frequently felt disrespected by having to adhere to terms imposed by Sparta, formed an alliance with Argos, one of Sparta’s biggest rivals next to Athens. Athens also lent support to Argos, but then the Corinthians withdrew. Fighting took place between Argos and Sparta, and the Athenians were involved. This was not their war, but it showed that Athens was still interested in picking a fight with Sparta.

Another important event, or series of events, that took place in the years leading up to the final stage of the war was Athens attempts to expand. Athenian leadership had been following a policy for many years that it was better to be the ruler than the ruled, which provided justification for sustained imperial expansion. They invaded the island of Melos, and then they sent a massive expedition to Sicily in an attempt to subjugate the city of Syracuse. They failed, and thanks to the support of the Spartans and the Corinthians, Syracuse remained independent. But this meant Athens and Sparta were once again at war with one another.

Lysander Marches to Spartan Victory

Spartan leadership made changes to the policy that helots had to return to harvest each year, and they also established a base at Decelea, in Attica. This means that Spartan citizens now the men and the means to launch a full-scale attack on the territory surrounding Athens. Meanwhile, the Spartan fleet sailed around the Aegean to liberate cities from Athenian control, but they were beaten by the Athenians at the Battle of Cynossema in 411 BCE. The Athenians, led by Alcibiades, followed this victory up with another impressive defeat of the Spartan fleet at Cyzicus in 410 BCE. However, political turmoil in Athens halted their advance and left the door wide open for a Spartan victory.

One of the Spartan kings, Lysander, saw this opportunity and decided to exploit it. The raids into Attica had rendered the territory surrounding Athens almost entirely unproductive, and this meant they were entirely dependent on their trade network in the Aegean to get them the basic supplies for life. Lysander choice to attack this weakness by sailing straight for the Hellespont, the strait separating Europe from Asia near to the site of modern-day Istanbul. He knew most of the Athenian grain passed through this stretch of water, and that taking it would devastate Athens. In the end, he was right, and Athens knew it. They sent a fleet to confront him, but Lysander was able to lure them into a bad position and destroy them. This took place in 405 BCE, and in 404 BCE Athens agreed to surrender.

After the War

With Athens surrendering, Sparta was free to do as it wished with the city. Many within the Spartan leadership, including Lysander, argued for burning it to the ground to ensure there would be no more war. But in the end, they chose to leave it so as to recognize its significance to the development of Greek culture. However, Lysander managed to take control of the Athenian government n exchange for not getting his way. He worked to get 30 aristocrats with Spartan ties elected in Athens, and then he oversaw a harsh rule meant to punish the Athenians.

This group, known as the Thirty Tyrants, made changes to the judicial system so as to undermine democracy, and they began placing limits on individual freedoms. According to Aristotle, they killed some 5 percent of the city’s population, dramatically changing the course of history and earning Sparta the reputation of being undemocratic.

This treatment of the Athenians is evidence of a change of perspective in Sparta. Long proponents of isolationism, the Spartan citizens now saw themselves alone atop the Greek world. In the coming years, just as their rivals the Athenians did, the Spartans would seek to expand their influence and maintain an empire. But it would not last long, and in the grand scheme of things, Sparta was about to enter a final period that can be defined as decline.

A New Era in Spartan History: The Spartan Empire

The Peloponnesian War officially came to an end in 404 BCE, and this marked the beginning of a period of Greek history defined by Spartan hegemony. By defeating Athens, Sparta took control of many of the territories previously controlled by Athenians, giving birth to the first ever Spartan empire. However, over the course of the fourth century B.C, Spartan attempts to extend their empire, plus conflicts within the Greek world, undermined Spartan authority and eventually led to the end of Sparta as a major player in Greek politics.

Testing The Imperial Waters

Shortly after the end of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta sought to expand its territory by conquering the city of Elis, which is located on the Peloponnese near Mt. Olympus. They appealed to Corinth and Thebes for support but did not receive it. However, they invaded anyway and took the city with ease, increasing the Spartan appetite for empire even more.

In 398 BCE, a new Spartan king, Agesilaus II, assumed power next to Lysander (there were always two in Sparta), and he set his sights on exacting revenge over the Persians for their refusal to let the Ionian Greeks live freely. So, he gathered an army of around 8,000 men and marched the opposite route that Xerxes and Darius had taken nearly a century before, through Thrace and Macedon, across the Hellespont, and into Asia Minor, and was met with little resistance. Fearing they could not stop the Spartans, the Persian governor in the region, Tissaphernes, first tried, and failed, to bribe Agesilaus II and then proceeded to broker a deal that forced Agesilaus II to stop his advance in exchange for the freedom of some Ionian Greeks. Agesilaus II took his troops into Phrygia and began planning for an attack.

However, Agesilaus II would never be able to complete his planned attack in Asia because the Persians, eager to distract the Spartans, began assisting many of Sparta’s enemies in Greece, which meant the Spartan king would need to return to Greece to keep Sparta’s hold on power.

The Corinthian War

With the rest of the Greek world keenly aware that the Spartans had imperial ambitions, there was an increased desire to antagonize Sparta, and in 395 BCE, Thebes, which had been growing more powerful, decided to support the city of Locris in its desire to collect taxes from nearby Phocis, which was an ally of Sparta. The Spartan army was sent to support Phocis, but the Thebans also sent a force to fight alongside Locris, and war was once again upon the Greek world.

Shortly after this happened, Corinth announced it would stand against Sparta, a surprising move given the two cities longstanding relationship in the Peloponnesian League. Athens and Argos also decided to join the fight, pitting Sparta up against almost the entire Greek world. Fighting took place at both land and sea throughout 394 BCE, but in 393 BCE, political stability in Corinth divided the city. Sparta came to the aid of the oligarchic factions seeking to maintain power and the Argives supported the democrats. The fight lasted three years and ended with an Argive/Athenian victory at the Battle of Lechaeum in 391 BCE.

At this point, Sparta tried to end the fighting by asking the Persians to broker peace. Their terms were to restore the independence and autonomy of all Greek city states, but this was rejected by Thebes, mainly because it had been building up a base of power on its own through the Boeotian League. So, fighting resumed, and Sparta was forced to take to the sea to defend the Peloponnesian coast from Athenian ships. However, by 387 BCE, it was clear that no side would be able to gain an advantage, so the Persians were once again called in to help negotiate peace. The terms they offered were the same – all Greek city states would remain free and independent – but they also suggested that refusing these terms would bring out the wrath of the Persian empire. Some factions tried to muster up support for an invasion of Persia in response to these demands, but there was little appetite for war at the time, so all parties agreed to peace. However, Sparta was delegated the responsibility of making sure the terms of the peace treaty were honored, and they used this power to immediately break up the Boeotian League. This greatly angered the Thebans, something that would come to haunt the Spartans later on.

The Theban War: Sparta vs. Thebes

The Spartans were left with considerable power after the Corinthian War, and by 385 BCE, just two years after peace had been brokered, they were once again working to expand their influence. Still led by Agesilaus II, the Spartans marched north into Thrace and Macedon, laying siege to and eventually conquering Olynthus. Thebes had been forced to allow Sparta to pass through its territory as they marched north towards Macedon, a sign of Thebes subjugation to Sparta. However, by 379 BCE, Spartan aggression was too much, and the Theban citizens launched a revolt against Sparta.

Around the same time, another Spartan commander, Sphodrias, decided to launch an attack on the Athenian port, Piraeus, but he retreated before reaching it and burned the land as he returned towards the Peloponnese. This act was condemned by Spartan leadership, but it made little difference to the Athenians, who were now motivated to resume fighting with Sparta more than ever before. They gathered their fleet and Sparta lost several naval battles near the Peloponnesian coast. However, neither Athens nor Thebes really wanted to engage Sparta in a land battle, for their armies were still superior. Furthermore, Athens was now faced with the possibility of being caught in between Sparta and the now-powerful Thebes, so, in 371 BCE, Athens asked for peace.

At the peace conference, however., Sparta refused to sign the treaty if Thebes insisted on signing it in Boeotia. This is because doing so would have accepted the legitimacy of the Boeotian League, something the Spartans did not want to do. This outraged Thebes and the Theban envoy left the conference, leaving all parties unsure if the war was still on. But the Spartan army clarified the situation by gathering and matching into Boeotia.

The Battle of Leuctra: The Fall of Sparta

In 371 BCE, the Spartan army marched into Boeotia and was met by the Theban army in the small town of Leuctra. However, for the first time in nearly a century, the Spartans were soundly beaten. This proved that the Theban-led Boeotian League had finally surpassed Spartan power and was ready to assume its position as the hegemon of ancient Greece. This loss marked the end of the Spartan empire, and it also marked the true beginning of the end for Sparta.

Part of the reason why this was such a significant defeat was that the Spartan army was essentially depleted. To fight as a Spartiate – a highly-trained Spartan soldier – one had to have Spartan blood. This made it difficult to replace fallen Spartan soldiers, and by the Battle of Leuctra, the Spartan force was smaller than it had ever been. Furthermore, this meant that the Spartans were dramatically outnumbered by helots, who used this to revolt more frequently and upend Spartan society. As a result, Sparta was in turmoil, and the defeat at the Battle of Leuctra all but relegated Sparta to the annals of history.

Sparta After Leuctra

While the Battle of Leuctra marks the end of classical Sparta, the city remained significant for several more centuries. However, the Spartans refused to join the Macedons, led first by Philip II and later by his son, Alexander the Great, in an alliance against the Persians, which led to the eventual fall of the Persian empire.

When Rome entered the scene, Sparta assisted it in the Punic Wars against Carthage, but Rome later teamed up with Sparta’s enemies in ancient Greece during the Laconian War, which took place in 195 BCE, and defeated the Spartans. After this conflict, the Romans overthrew the Spartan monarch, ending Sparta’s political autonomy. Sparta continued to be an important trading center throughout medieval times, and it is now a district in the modern-day nation of Greece. However, after the Battle of Leuctra, it was a shell of its formerly all-powerful self. The era of classical Sparta had ended.

Spartan Culture and Life

While the city was founded in the 8th or 9th century B.C, the golden age of Sparta lasted roughly from the end of the 5th century – the first Persian invasion of ancient Greece – until the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE. During this time, Spartan culture flourished. However, unlike their neighbors to the north, Athens, Sparta was hardly a cultural epicenter. Some artisanry did exist, but we see nothing in terms of philosophic or scientific advancements like those that came out of Athens in the final century B.C. Instead, Spartan society was based around the military. Power was held onto by an oligarchic faction, and individual freedoms for non-Spartans were severely restricted, although Spartan women may have had much better conditions than women living in other parts of the ancient Greek world. Here’s a snapshot of some of the key features of life and culture in classical Sparta.

Helots in Sparta

One of the key features of the social structure in Sparta were the helots. The term has two origins. First, it directly translates to “captive,’ and second, it’s believed to be closely linked to the city of Helos, the citizens of which were made into the first helots in Spartan society.

For all intents and purposes, the helots were slaves. They were needed because Spartan citizens, also known as Spartiates, were forbidden from doing manual labor, meaning they needed forced labor to work the land and produce food. In exchange, the helots were allowed to keep 50 percent of what they produced, were allowed to marry, practice their own religion, and, in some cases, own property. Yet they were still treated quite poorly by the Spartans. Each year, the Spartans would declare “war” on the helots, giving Spartan citizens the right to kill helots as they saw fit. Furthermore, helots were expected to go off to war when commanded to do so by Spartan leadership, the punishment for resisting being death.

National Archaeological Museum [CC BY-SA 3.0

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Typically, helots were Messenians, those who had occupied the region of Messenia before the Spartans conquered during the First and Second Messenian Wars fought in the 7th century B.C. This history, plus the poor treatment the Spartans gave to the helots, made them a frequent problem in Spartan society. Revolt was always right around the corner, and by the 4th century B.C, helots outnumbered Spartans, a fact they used to their advantage to win more freedoms and destabilize Sparta until it could no longer support itself as the Greek hegemon.

The Spartan Soldier

The armies of Sparta have gone down as some of the most impressive of all time. They achieved this status during the Greco-Persian wars especially the Battle of Thermopylae when a small force of Greeks led by 300 Spartan soldiers managed to fend off Xerxes and his massive armies, which included the then-superior Persian Immortals, for three days, inflicting heavy casualties. The Spartan soldier, also known as a hoplite, looked the same as any other Greek soldier. He carried a large bronze shield, wore bronze armor, and carried a long, bronze-tipped spear. Furthermore, he fought in a phalanx, which is an array of soldiers designed to create a strong line of defense by having each soldier protect not only himself but the soldier sitting next to him using a shield. Nearly all Greek armies fought using this formation, but the Spartans were the best, mainly because of the training a Spartan soldier had to go through before joining the military.

To become a Spartan soldier, Spartan men had to undergo training at the agoge, a specialized military school designed to train the Spartan army. Training in this school was grueling and intense. When Spartan boys were born, they were examined by members of the Gerousia (a council of leading elder Spartans) from the child’s tribe to see whether he was fit and healthy enough to be allowed to live. In the event that the Spartan boys did not pass the test, they were placed at the base of Mount Taygetus for several days for a test that ended with death by exposure, or survival. Spartan boys were often sent out into the wild on their own to survive, and they were taught how to fight. However, what set the Spartan soldier apart was his loyalty to his fellow soldier. In the agoge, the Spartan boys were taught to depend on one another for the common defense, and they learned how to move in formation so as to attack without breaking ranks.

Spartan boys were also instructed in academics, warfare, stealth, hunting and athletics. This training provided to be effective on the battlefield as the Spartans were virtually unbeatable. Their only major defeat, the Battle of Thermopylae, occurred not because they were an inferior fighting force but rather because they were hopelessly outnumbered and betrayed by a fellow Greek who told Xerxes of the way around the pass.

At the age of 20, Spartan men would become warriors of the state. This military life would go on until they turned 60. While much of the lives of Spartan men would be ruled by discipline and military, there were also other options over time available to them. For instance as a member of the state at age twenty, Spartan men were allowed to marry, but they would not share a marital home until they were thirty or older. For now their lives were dedicated to the military.

When they clocked thirty, Spartan men became full citizens of the state, and as such they were granted various privileges. The newly granted status meant Spartan men could live at their homes, most of the Spartans were farmers but the helots would work the land for them. If Spartan men would get to the age of sixty they would be considered retired. After sixty the men would not have to perform any military duties, this included all war-time activities.

Spartan men were also said to wear their hair long, often braided into locks. long hair symbolized being a free man and as Plutarch claimed, “..it made the handsome more comely and the ugly more frightful”. Spartan men were generally well groomed.

However, the overall effectiveness of Sparta’s military might was limited due to the requirement that one be a Spartan citizen to participate in the agoge. Citizenship in Sparta was taught to acquire, as one had to prove their blood relation to an original Spartan, and this made it difficult to replace soldiers on a one to one basis. Over time, particularly after the Peloponnesian War during the period of the Spartan Empire, these put considerable strain on the Spartan army. They were forced to rely more and more on helots and other hoplites, who not as well-trained and therefore beatable. This finally became apparent during the Battle of Leuctra, which we now see as the beginning of the end for Sparta.

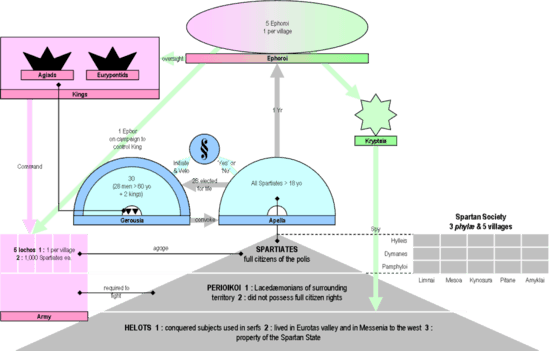

Spartan Society and Government

While Sparta was technically a monarchy governed by two kings, one each from the Agiad and Eurypontid families, these kings were relegated over time to positions that most closely resembled generals. This is because the city was really governed by the ephors and gerousia. The gerousia was a council of 28 men over the age of 60. Once elected, they held their post for life. Typically, members of the gerousia were related to one of the two royal familes, which helped to keep power consolidated in the hands of the few.

The gerousia was responsible for electing the ephors, which is the name given to a group of five officials who were responsible for carrying out the orders of the gerousia. They would impose taxes, deal with subordinate helot populations, and accompany kings on military campaigns to ensure the wishes of the gerousia were met. To be a member of these already exclusive leading parties, one had to be a Spartan citizen, and only Spartan citizens could vote for the gerousia. Because of this, there is no doubt that Sparta operated under an oligarchy, a government ruled by the few. Many believe this arrangement was made because of the nature of the founding of Sparta; the combining of four, and then five, towns meant that leaders of each needed to be accommodated, and this form of government made this possible.

Publius97 at en.wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Next to the ephors, the gerousia, and kings, were the clergy. Spartan citizens were also considered to be at the top of the Spartan social order, and below them were helots and other non-citizens. Because of this, Sparta would have been a highly unequal society where wealth and power were accumulated into the hands of the few and those without citizen status were denied basic rights.

Spartan Kings

One unique thing about Sparta was that it had always had two kings ruling simultaneously. The leading theory about why this was the case deals with the founding of Sparta. It is thought that the original villages made this arrangement to ensure that each powerful family got a say but also so that neither village could gain too much of an advantage over the other. Plus, the gerousia was established to further weaken the power of the Spartan kings and limit their ability to rule autonomously. In fact, by the time of the Peloponnesian War, the Spartan kings had little or no say over the affairs of the Spartan polis. Instead, by this point, there were relegated to nothing more than generals, but they were even limited in how they could act in this capacity, meaning most of the power in Sparta was in the hands of the gerousia.

Sparta’s two kings ruled by divine right. Both royal families, the Agiads and the Eurypontids, claimed ancestry with the gods. Specifically, they traced their ancestry to Eurysthenes and Procles, the twin children a Heracles, one of the sons of Zeus.

READ MORE: Greek gods and goddesses

Because of their history and significance to society, Sparta’s two kings still played an important role in helping Sparta rise to power and become the significant city state it was, despite their role being limited by the formation of the gerousia. Some of these kings include, from the Agiad dynasty:

- Agis I (c. 930 BCE-900 BCE) – known for leading the Spartans in subjugating the territories of Laconia. His line, the Agiads, is named after him.

- Alcamenes (c. 758-741 BCE) – Spartan king during the First Messenian War

- Cleomenes I (c. 520-490 BCE) – Spartan king who oversaw the beginning of the Greco-Persian Wars

- Leonidas I (c. 490-480 BCE) – Spartan king who led Sparta, and died fighting, during the Battle of Thermopylae

- Agesipolis I (395-380 BCE) – Agiad king during the Corinthian War

- Agesipolis III (c. 219-215 BCE) – the last Spartan king from the Agiad dynasty

From the Eurypontid dynasty, the most important kings were:

- Leotychidas II (c. 491 -469 BCE) – helped lead Sparta during the Greco-Persian War, taking over for Leonidas I when he died at the Battle of Thermopylae.

- Archidamus II (c. 469-427 BCE) – led the Spartans during much of the first part of the Peloponnesian War, which is often called the Archidamian War

- Agis II (c. 427-401 BCE) – oversaw the Spartan victory over Athens in the Peloponnesian War and ruled over the early years of Spartan hegemony.

- Agesilaus II (c. 401-360 BCE) – Commanded the Spartan army during the period of the Spartan empire. Ran campaigns in Asia to free the Ionian Greeks, and stopped his invasion of Persia only because of the turmoil occurring in ancient Greece at the time.

- Lycurgus (c. 219-210 BCE) – deposed the Agiad king Agesipolis III and became the first Spartan king to rule alone

- Laconicus (c. 192 BCE) – the last known king of Sparta

Spartan Women

While many parts of Spartan society were considerably unequal, and freedoms were limited for all but the most elite, Spartan women were granted a much more significant role in Spartan life than they were in other Greek cultures at the time. Of course, they were far from equals, but they were afforded freedoms unheard of in the ancient world. For example, as compared to Athens where women were restricted from going outside, had to live in their father’s house, and were required to wear dark, concealing clothing, Spartan women were not only allowed but encouraged to go outside, exercise, and wear clothing that allowed them more freedom.

Explore More Ancient History Articles

Julianus

Vesta: The Roman Goddess of the Home and the Hearth

Ancient Egyptian Food: More Than Beer and Bread

Constantine the Great: Who Was Constantine and What Did He Accomplish?

The Nine Greek Muses: Goddesses of Inspiration

Roman Weapons: Roman Weaponry and Armor

They were also fed the same foods as Spartan men, something that did not happen in many parts of ancient Greece, and they were restricted from bearing children until they were in their late teens or twenties. This policy was meant to improve the chances of Spartan women having healthy children while also preventing women from experiencing the complications that come from early pregnancies. They were also allowed to sleep with other men besides their husbands, something that was completely unheard of in the ancient world. Furthermore, Spartan women were not allowed to participate in politics, but they did have the right to own property. This likely came from the fact that Spartan women, often left alone by their husbands during times of war, became the administrators of men’s property, and if their husbands died, that property often became theirs. Spartan women were seen as the vehicle by which the city of Sparta constantly advanced

Of course, as compared to the world we live in today, these freedoms hardly seem significant. But considering the context, one in which women were typically seen as second-class citizens, this relatively equal treatment of Spartan women set this city apart from the rest of the Greek world.

Remembering classical Sparta

The story of Sparta is certainly an exciting one. A city that virtually didn’t exist until the end of the first millennium BCE, it rose to be one of if not the most powerful cities in ancient Greece as well as the entire Greek world. Over the years, Spartan culture has become quite famous, with many pointing to the austere mannerisms of its two kings along with its commitment to loyalty and discipline, as evidenced by the Spartan army. And while these may be exaggerations of what life was really like in Spartan history, it’s difficult to overstate Spartan significance in ancient history as well as the development of world culture.

Bibliography

Bradford, Alfred S. Leonidas and the Kings of Sparta: Mightiest Warriors, Fairest Kingdom. ABC-CLIO, 2011.

Cartledge, Paul. Hellenistic and Roman Sparta. Routledge, 2004.

Cartledge, Paul. Sparta and Lakonia: a regional history 1300-362 BC. Routledge, 2013.

Feetham, Richard, ed. Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War. Vol. 1. Dent, 1903.

Kagan, Donald, and Bill Wallace. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003.

Powell, Anton. Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek political and social history from 478 BC. Routledge, 2002.

Lysander was not a basileus of Sparta. He was not a royal.