Monumental advances in math, science, philosophy, government, literature, and art have made the Ancient Greeks the envy of world’s past and present. The Greeks gave us democracy, the scientific method, geometry, and so many more building blocks of civilization that it’s hard to imagine where we would be without them.

However, images of Ancient Greece as a peaceful world where art and culture thrived above everything else are simply wrong. War was just as common as anything else, and it plays a critical role in the story of Ancient Greece.

The Peloponnesian War, fought between Athens and Sparta (two leading ancient Greek city states) from 431 to 404 BCE, is perhaps the most important and also the most well-known of all these conflicts as it helped redefine the balance of power in the ancient world.

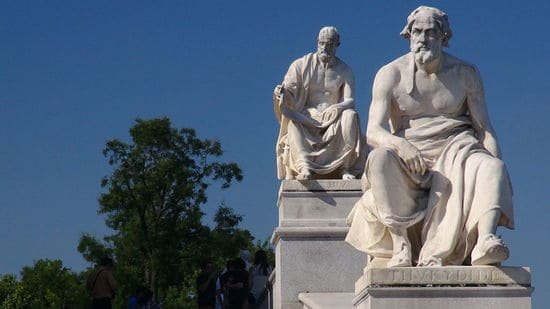

The Peloponnesian War is also significant because it’s one of the first wars documented in a reliable way. The ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who many consider the world’s first true historian, spent time traveling to the various theaters of war to interview generals and soldiers alike, and he also analyzed many of the long- and short-term causes of the Peloponnesian war, an approach still taken by military historians today.

His book, The Peloponnesian War, is the point of reference for studying this conflict, and it has helped us understand so much of what was going on behind the scenes. Using this source, as well as a range of other primary and secondary sources, we have put together a detailed summary of this famous ancient conflict so that you can better understand this momentous period of human history. Although the term “Peloponnesian War” was never used by Thucydides, the fact that the term is all but universally used today is a reflection of the Athens-centric sympathies of modern historians.

GuentherZ [CC BY-SA 3.0 at (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/at/deed.en)]

Table of Contents

The Peloponnesian War At a Glance

The Peloponnesian war lasted 27 years, and it occurred for many different reasons. But before going into all the details, here are the main points to remember:

Who Fought in the Peloponnesian War?

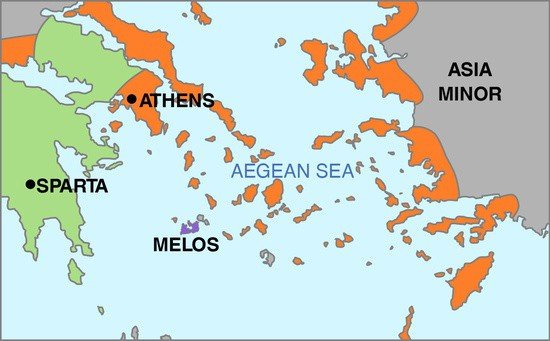

The Peloponnesian War was fought mainly between Athens and Sparta. However, rarely did the two sides fight each other alone. Athens was part of the Delian League, an alliance of ancient Greek-city states led and funded mainly by Athens that eventually morphed into the Athenian Empire, and Sparta was a member of the Peloponnesian League. This alliance, made up mostly of city-states on the Peloponnese, the southernmost peninsula of the Greek mainland, was much less formal than the Delian League. It was designed to provide common defense for members, but it did not have the same political organization as the Delian League, although Sparta served as the leader of the group for most of its existence.

What Were the Main Reasons for the Peloponnesian War?

Part of the reason Thucydides’ historical account of the Peloponnesian war is so significant is that it was one of the first times a historian put effort into determining both the short-and long-term causes of war. Long-term causes are usually tied to ongoing geopolitical and trade conflicts, whereas short term causes are the proverbial “straws that break the camel’s back.” Historians since have spent time dissecting the causes outlined by Thucydides, and most agree the long-term motivations were:

- Athenian imperial ambitions that were perceived by Sparta as an infringement on their sovereignty and a threat to their isolationist policy. Nearly fifty years of Greek history before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War had been marked by the development of Athens as a major power in the Mediterranean world.

- A growing appetite for war amongst the male Greek youth that was the result of the legendary stories told about the Greco-Persian Wars.

As far as short term causes, most historians agree that the attack on a Theban envoy made by the citizens of Plataea was what finally drove these two city-states to war. Thebes was allied at the time with Athens, and Plataea was linked to Sparta. Killing this envoy was seen as a betrayal, and both Athens and Sparta sent troops in response, breaking the peace that had defined the previous 15 years and setting the Peloponnesian War in motion.

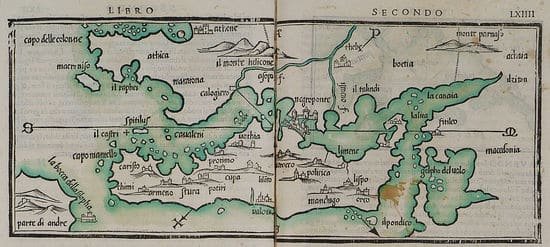

Where Was the Peloponnesian War Fought?

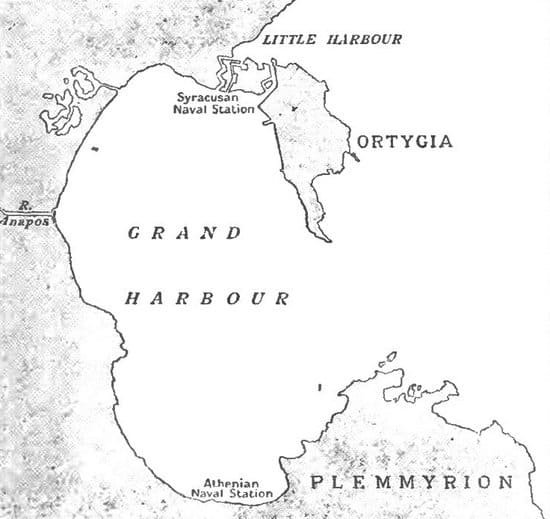

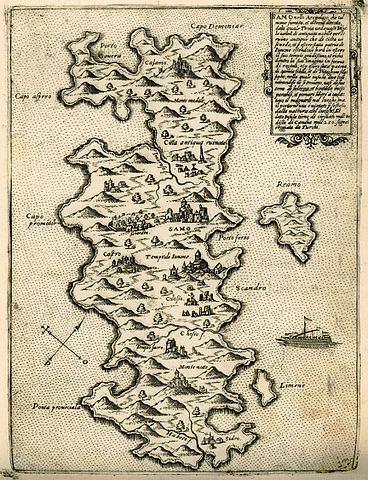

Most of the fighting took place on the Peloponnese, the peninsula where Sparta is located, Attica, the region in which Athens is located, as well as the islands of the Aegean Sea. However, a major part of the Peloponnesian war also occurred on the island of Sicily, which at the time was settled by Greeks, as well as Ionia, the region on the southern coast of modern-day Turkey that had been home to ethnic Greeks for centuries. Naval battles were also fought throughout the Aegean Sea.

When Was the Peloponnesian War Fought?

The Peloponnesian War lasted 27 years between 431 BCE and 404 BCE.

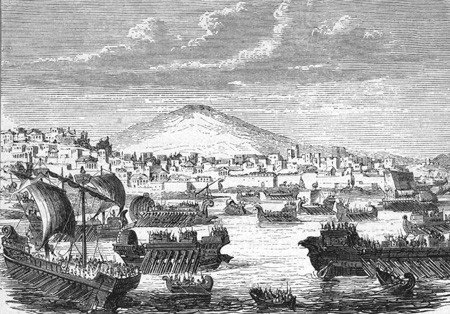

How Was the Peloponnesian War Fought?

The Peloponnesian War was fought over land and sea. At the time, the Athenians were the top naval power in the ancient world, and the Spartans were the premier land fighting force. As a result, the Peloponnesian war featured many battles where one side was forced to fight to the other side’s strengths. However, strategic alliances, as well as an important shift in Spartan policy that allowed them to run more frequent raids on Athenian soil, eventually allowed Sparta to gain an edge over its opponent.

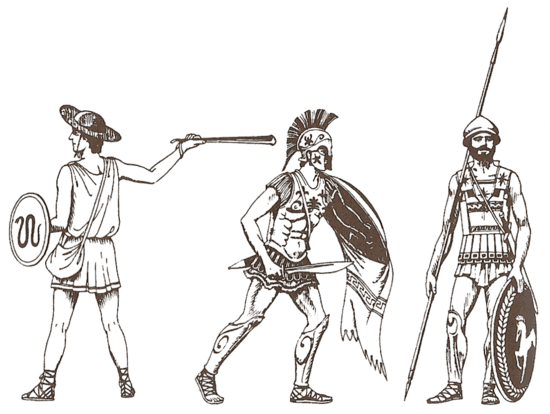

Warfare in the Second Peloponnesian War became more sophisticated and more deadly with the conventions of warfare breaking down and resulting in atrocities previously unthinkable in Greek warfare. Civilians became much more involved in the Peloponnesian war and entire citizen bodies could be wiped out as happened at in Boeotia and Mykalessos.

Like all great wars, the Peloponnesian War brought about changes and developments in warfare. The heavily armed hoplite in the phalanx formation (lines of closely packed hoplites protecting each other with their shields) still dominated the Greek battlefield but the phalanx did become deeper (more rows of men) and wider (a longer front of men) during the Peloponnesian War.

Who Won the Peloponnesian War?

Sparta emerged from this conflict as victors, and in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian war, the Spartans created the first empire in their history. However, this would not last long. Tensions within the Greek world remained and the Spartans were eventually removed as the Greek hegemon.

The Peloponnesian War Map

The Peloponnesian War

Although The Peloponnesian War was technically fought between 431 and 404 BCE, the two sides did not fight constantly, and the war broke out as a result of conflicts that had been brewing for a better part of the 5th century BCE. As such, to really understand the Peloponnesian war and its significance in ancient history, it’s important to turn the clock back and see how and why Athens and Sparta had become such bitter rivals.

Before the Outbreak of the War

Fighting between Greek city-states, also known as poleis, or the singular, polis, was a common theme in Ancient Greece. Although they shared a common ancestry, ethnic differences, as well as economic interests, and an obsession with heroes and glory, meant that war was a common and welcomed occurrence in the ancient Greek world. However, despite being relatively close to one another geographically, Athens and Sparta rarely engaged in direct military conflict during the centuries leading up to the Peloponnesian War.

This changed, ironically, after the two sides actually came together to fight as part of a pan-Greek alliance against the Persians. This series of conflicts, known as the Greco-Persian Wars, threatened the very existence of the ancient Greeks. But the alliance eventually exposed the conflicting interests between Athens and Sparta, and this is one of the main reasons why the two eventually went to war.

The Greco-Persian War: Setting the Stage for the Peloponnesian War

The Greco-Persian War took place over fifty years between 499 and 449 BCE. At the time, the Persians controlled large swaths of territory that spanned from modern-day Iran to Egypt and Turkey. In an effort to continue to expand his empire, the Persian king at the turn of the 5th century BCE, Darius I, convinced a Greek tyrant, Aristagoras, to invade the Greek island Naxos on his behalf. However, he failed, and fearing retaliation from the Persian king, Aristagoras encouraged the Greeks living throughout Ionia, the region on the southern coast of modern-day Turkey, to rebel against the Persian throne, which they did. Darius I responded by sending his army and campaigning around the region for ten years to quell the insurrection.

Once this chapter of the war was over, Darius I marched into Greece with his army so as to punish those who had offered support to the Ionian Greeks, mainly Athens and Sparta. However, he was stopped at the Battle of Marathon (490 BCE), and he died before he was able to regroup his army and launch another attack. His successor, Xerxes I, gathered one of the largest armies ever assembled in the ancient world and marched into Greece with the aim of subjugating Athens, Sparta, and the rest of the free Greek city-states.

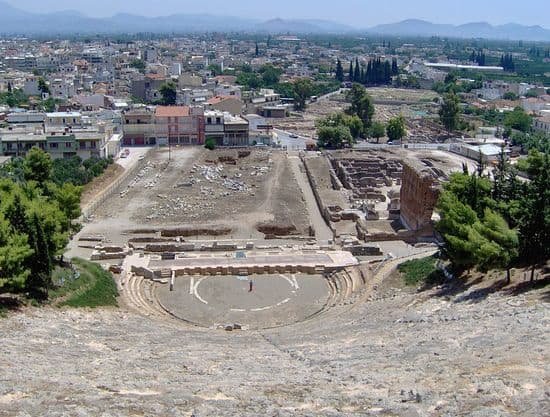

Forming the Greek Alliance

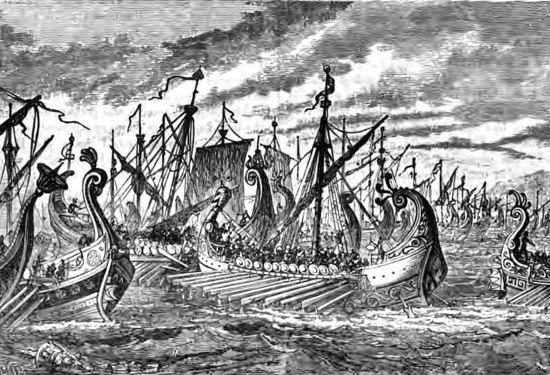

In response, Athens and Sparta, along with several other powerful city-states, such as Corinth, Argos, and Arcadia, formed an alliance to fight against the invading Persians, and this joint force was eventually able to stop the Persians at the Battle of Salamis (480 BCE) and the Battle of Plataea (479 BCE). Before these decisive battles which ended in Greek victories, the two sides fought the Battle of Thermopylae, which is one of the most famous battles of the ancient era.

These two defeats drove Xerxes and his armies from Greece, but it did not end the war. Disagreements about how to proceed in the fight against Persia broke out, with Athens and Sparta having different opinions about what to do. This conflict played an important role in the eventual outbreak of war between the two Greek cities.

The Seeds of War

The disagreement emerged for two main reasons:

- Athens felt Sparta was not contributing enough to the defense of ancient Greece. At the time, Sparta had the most formidable army in the Greek world, yet it continuously refused to commit a significant amount of troops. This angered Athens so much that its leaders at one point threatened to accept Persian peace terms if Sparta didn’t act.

- After the Persians were defeated at the Battles of Plataea and Salamis, Spartan leadership felt the pan-Greek alliance that had been formed had served its purpose and should therefore be dissolved. However, the Athenians felt it was necessary to pursue the Persians and push them further away from Greek territory, a decision that caused the war to continue for another 30 years.

However, during this final period of the war, Athens fought without the help of Sparta. The pan-Greek alliance had morphed into another alliance the Delian League, named for the island of Delos where the League had its treasury. Using the power and resources of its allies, Athens began to expand its influence in the region, which has caused many historians to swap the name “Delian League” for Athenian Empire.

The Spartans, who were historically isolationist and had no imperial ambitions, but who treasured their sovereignty above all else, saw expanding Athenian power as a threat to Spartan independence. As a result, when the Greco-Persian War came to an end in 449 BCE, the stage was set for the conflict which would eventually be known as the Peloponnesian War.

The First Peloponnesian War

While the main conflict fought between Athens and Sparta is known as The Peloponnesian War, this was not the first time these two city-states fought. Shortly after the end of the Greco-Persian War, a series of skirmishes broke out between Athens and Sparta, and historians often call this the “First Peloponnesian War.” Although it didn’t reach anywhere near the scale of the conflict that was to come, and the two sides rarely fought one another directly, these series of conflicts help show how tense relations were between the two cities.

I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

The First Peloponnesian war has its roots in the mid-460s BCE, a period when Athens was still fighting the Persians. Sparta called upon Athens to assist in the putting down a helot rebellion in Spartan territory. Helots were essentially slaves who did most if not all of the manual labor in Sparta. They were essential to the city-state’s prosperity, yet because they were denied many of the rights of Spartan citizens, they rebelled frequently and caused considerable political unrest throughout Sparta. However, when the Athenian army arrived in Sparta, they were sent away for reasons unknown, a move that greatly angered and insulted Athenian leadership.

Once this happened, Athens feared the Spartans would make a move against them, so they began reaching out to other Greek city-states to secure alliances in the event there was an outbreak of fighting. The Athenians started by striking deals with Thessaly, Argos, and Megara. To escalate things further, Athens began allowing helots who were fleeing Sparta to settle in and around Athens, a move that not only angered Sparta but that destabilized it even more.

The Fighting Begins

By 460 BCE, Athens and Sparta were essentially at war, although they rarely fought one another directly. Here are some of the main events to take place during this initial conflict known as the First Peloponnesian War.

- Sparta sent forces to support Doris, a city-state in Northern Greece with which it maintained a strong alliance, in a war against Phocis, an ally of Athens. The Spartans helped the Dorians secure a victory, but Athenian ships blocked the Spartans from leaving, a move which angered the Spartans greatly.

- The Spartan army, blocked from escaping by sea, marched to Boeotia, the region in which Thebes is located, and they managed to secure an alliance from Thebes. The Athenians responded and the two fought the Battle of Tangara, which Athens won, giving them control over large portions of Boeotia.

- Athens won another victory at Oenophyta, which allowed them to conquer almost all of Boeotia. From there, the Athenian army marched south towards Sparta.

- Athens conquered Chalcis, a city-state near the Corinthian Gulf which gave Athens direct access to the Peloponnese, putting Sparta in tremendous danger.

At this point in the First Peloponnesian War, it appeared as though Athens was going to deliver a decisive blow, an event that would have dramatically changed the course of history. But they were forced to stop because the force they had sent to Egypt to fight the Persians (who controlled most of Egypt at the time), had been badly defeated, leaving the Athenians vulnerable to a Persian retaliation. As a result, they were forced to stop their pursuit of the Spartans, a move which helped cool off the conflict between Athens and Sparta for some time.

Sparta Strikes Back

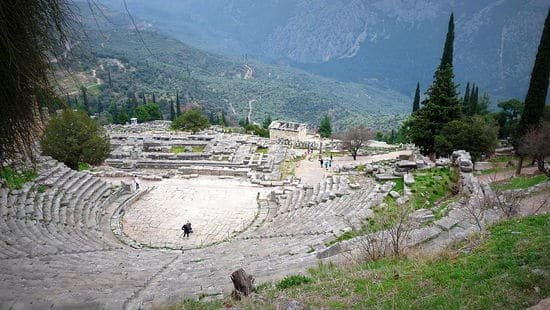

Recognizing Athens’ weakness, the Spartans decided to try and turn the tables. They entered Boeotia and provoked a revolt, which Athens tried, but failed, to squash. This move meant the Athenian Empire, activating under the guise of the Delian League, no longer had any territory on mainland Greece. Instead, the empire was relegated to the islands throughout the Aegean. Sparta also made a declaration that Delphi, the city that housed the famous Greek oracle, was to be independent from Phocis, one of Athens’ allies. This move was largely symbolic, but it showed Spartan defiance to Athens’ attempt to be the premier power in the Greek world.

Donpositivo [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

After the revolt in Boeotia, several island city-states that had been part of the Delian League decided to rebel, the most significant being Megara. This distracted Athens from the Spartan threat and Sparta tried to invade Attica during this time. However, they failed, and it had become clear to both sides the war was going nowhere.

The Thirty Years’ Peace

The First Peloponnesian War ended in an arrangement between Sparta and Athens, which was ratified by the “Thirty Years’ Peace” (winter of 446–445 BC). As the name suggests, it was meant to last thirty years, and it set up a framework for a divided Greece that was led by both Athens and Sparta. More specifically, neither side could go to war with one another if one of the two parties advocated for settling the conflict through arbitration, language that essentially recognized Athens and Sparta as equally powerful in the Greek world.

Accepting these peace terms all but ended the aspiration some Athenian leaders had of making Athens the head of a unified Greece, and it also marked the peak of Athenian imperial power. However, the differences between Athens and Sparta proved to be too much. Peace lasted much less than thirty years, and soon after the two sides agreed to put down their weapons, The Peloponnesian War broke out and the Greek world was changed forever.

The Peloponnesian War

It’s impossible to know if Athens and Sparta truly believed their peace agreement would last the full thirty years it was supposed to. But that the peace came under intense pressure in 440 BCE, just six years after the treaty was signed, helps show just how fragile things were.

Conflict Resumes Between Athens and Sparta

This near breakdown in cooperation took place when Samos, a powerful ally of Athens at the time, chose to revolt against the Delian League. The Spartans saw this as a major opportunity to perhaps once and for all put an end to Athenian power in the region, and they called a congress of their allies in the Peloponnesian Alliance to determine if the time had indeed come to resume conflict against the Athenians. However, Corinth, one of the few city-states in the Peloponnesian League that could stand up to Sparta’s power, was adamantly opposed to this move, and so the notion of war was tabled for some time.

The Corcyrean Conflict

Just seven years later, in 433 BCE, another major event took place that once again put considerable strain on the peace that Athens and Sparta had agreed to maintain. In short, Corcyra, another Greek city-state which was located in northern Greece, picked a fight with Corinth over a colony located in what is now modern-day Albania.

Berthold Werner [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

This colony, which had been ruled by a Corcyrean oligarchy since its inception, had become wealthy and was seeking to install a democracy. The wealthy merchants hoping to overthrow the oligarchy appealed to Corinth for help, and they got it. But then the Corcyraeans asked Athens to step in, which they did. However, knowing that involving itself with one of Sparta’s closest allies could mean trouble between Athens and Sparta, the Athenians sent a fleet that was instructed to only engage in defensive maneuvers. But when they got to the battle, they ended up fighting, which only escalated things further.

This engagement became known as the Battle of Sybota, and it put the Thirty Years’ Peace to its biggest test yet. Then, when Athens decided to punish those who had offered support to Corinth, war started to become even more imminent.

The Peace is Broken

Seeing that Athens was still set on expanding its power and influence in Greece, the Corinthians requested that the Spartans call together the various members of the Peloponnesian League to discuss the matter. The Athenians, however, showed up uninvited to this congress, and a great debate, recorded by Thucydides, took place. At this meeting of the various heads of state in the Greek world, the Corinthians shamed Sparta for standing on the sidelines while Athens continued to try and bring free Greek city-states under its control, and it warned that Sparta would be left without any allies if it continued its inaction.

The Athenians used their time on the floor to warn the Peloponnesian alliance what could happen if war resumed. They reminded everyone of how the Athenians were the principle reason the Greeks managed to stop the great Persian armies of Xerxes, a claim that is debatable at best but essentially just false. On this premise, Athens argued that Sparta should seek out a resolution to the conflict through arbitration, a right it had based on the terms of the Thirty Years’ Peace.

However, the Spartans, along with the rest of the Peloponnesian League, agreed the Athenians had already broken the peace and that war was once again necessary. In Athens, politicians would claim the Spartans had refused to arbitrate, which would have positioned Sparta as the aggressor and made the war more popular. However, most historians agree this was merely propaganda designed to win support for a war Athenian leadership wanted in its quest to expand its power.

The Peloponnesian War Begins

At the end of this conference held among the major Greek city-states, it was clear that war between Athens and Sparta was going to happen, and just one year later, in 431 BCE, fighting between the two Greek powers resumed.

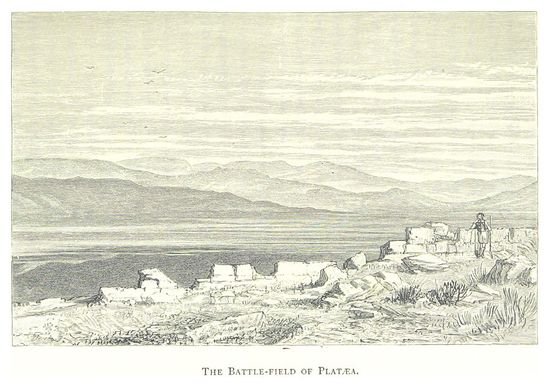

The scene was the city of Plataea, famous for the Battle of Plataea in which the Greeks won a decisive victory over the Persians. However, this time, there would be no major battle. Instead, a sneak attack by the citizens of Plataea would set in motion arguably the greatest war of Greek history.

In short, an envoy of 300 Thebans went to Plataea to help a group of elites overthrow the leadership in Plataea. They were granted access to the city, but once inside, a group of Plataean citizens rose up and killed nearly the entire envoy. This set off a rebellion inside the city of Plataea, and the Thebans, along with their allies the Spartans, sent troops to support those who had been trying to seize power in the first place. The Athenians supported the government in power, and this meant the Athenians and the Spartans were fighting once again. This event, while somewhat random, help set into motion 27 years of conflict that we now understand as the Peloponnesian War.

Part 1: The Archidamian War

Because The Peloponnesian War was such a long conflict, most historians break it up into three parts, with the first being called the Archidamian War. The name comes from the Spartan king at the time, Archidamus II. The Archidamian War did not start without serious disturbances in the Greek balance of power. This initial chapter lasted for ten years, and its events help show just how difficult it was for either side to gain an advantage of the other. More specifically, the impasse between the two sides was largely the result of Sparta having a strong ground force but weak navy and Athens having a powerful navy but less effective ground force. Other things, such as restrictions on how long Spartan soldiers could be away at war, also contributed to the lack of a decisive result from this initial part of the Peloponnesian war.

As mentioned, the Archidamian war officially broke out after the Plataea sneak attack in 431 BCE, and the city remained under siege by the Spartans. The Athenians committed a small defense force, and it proved to be rather effective, as Spartan soldiers were not able to break through until 427 BCE. When they did, they burned the city to the ground and killed the surviving citizens. This gave Sparta an initial edge in the Peloponnesian war, but Athens hadn’t committed anywhere near enough troops for this defeat to have a significant effect on the overall conflict.

The Athenian Defense Strategy

Recognizing the supremacy of Sparta’s infantry, the Athenians, under the leadership of Pericles, decided it was in their best interest to take a defensive strategy. They would use their naval supremacy to attack strategic ports along the Peloponnese while relying on the high city-walls of Athens to keep the Spartans out.

However, this strategy left much of Attica, the peninsula on which Athens is located, completely exposed. As a result, Athens opened its city walls to all residents of Attica, which caused the population of Athens to swell considerably during the early stages of the Peloponnesian War.

This strategy ended up backfiring slightly as a plague broke out in Athens in 430 BCE that devastated the city. It’s believed somewhere around one-third to two-thirds of the Athenian population died during three years of plague. The plague also claimed the life of Pericles, and this passive, defensive strategy died with him, which opened the door to a wave of Athenian aggression on the Peloponnese.

The Spartan Strategy

Because the Athenians had left Attica almost entirely undefended, and also because the Spartans knew they had a significant advantage in land battles, the Spartan strategy was to raid the land surrounding Athens so as to cut off the food supply to the city. This worked in the sense that the Spartans burned considerable swaths of territory around Athens, but they never dealt a decisive blow because Spartan tradition required soldiers, mainly the helot soldiers, to return home for the harvest each year. This prevented Spartan forces from getting deep enough into Attica to threaten Athens. Furthermore, because of the Athens’ extensive trade network with the many city-states scattered around the Aegean, Sparta was never able to starve its enemy in the way it had intended.

Athens Goes on the Attack

He was a prominent and influential Greek statesman, orator and general of Athens during its golden age.

After Pericles died, Athenian leadership came under the control of a man named Cleon. As a member of political factions within Athens that most desired war and expansion, he almost immediately changed the defensive strategy Pericles had devised.

In Sparta, full citizens were forbidden from doing manual labor, and this meant that nearly all of Sparta’s food supply depended on the forced labor of these helots, many of whom were the subjects or descendants of cities on the Peloponnese conquered by Sparta. However, helot rebellions were frequent and they were a significant source of political instability within Sparta, which presented Athens with a prime opportunity to hit their enemy where it would hurt the most. Athens’ new offensive strategy was to attack Sparta at its weakest point: its dependence on helots. Before too long, Athens would be encouraging the helots to revolt so as to weaken Sparta and pressure them into surrendering.

Before this, though, Cleon wanted to remove the Spartan threat from other parts of Greece. He ran campaigns in Boeotia and Aetolia to drive back the Spartan forces stationed there, and he was able to have some success. Then, when the Spartans backed a revolt on the island of Lesbos, which at the time was a part of the Delian alliance/Athenian Empire, Athens responded ruthlessly, a move which actually lost Cleon a good deal of his popularity at the time. With these issues under his control, Cleon then moved to attack the Spartans on their home territory, a move which would prove to be rather significant not only in this part of the conflict but also in the entire Peloponnesian War.

The Battle of Pylos

Throughout the early years of the Peloponnesian war, Athenians, under the leadership of the naval commander Demosthenes, had been attacking strategic ports on the Peloponnesian coast. Due to the relative weakness of the Spartan navy, the Athenian fleet was met with little resistance as it raided smaller communities along the coast. However, as the Athenians made their way around the coast, helots frequently ran to meet the Athenians, as this would have meant freedom from their destitute existence.

Pylos, which is located on the southwestern coast of the Peloponnese, became an Athenian stronghold after the Athenians won a decisive battle there in 425 BCE. Once under Athenian control, helots began flocking to the coastal stronghold, putting further strain on the Spartan way of life. Furthermore, during this battle, the Athenians managed to capture 420 Spartan soldiers, largely because the Spartans got trapped on an island just outside Pylos’ harbor. To make things worse, 120 of these soldiers were Spartiates, elite Spartan soldiers who were both an important part of the Spartan military and society.

Museum of the Ancient Agora [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

As a result, Spartan leadership sent an envoy to Pylos to negotiate an armistice that would secure the release of these soldiers, and to show they were negotiating in good faith, this envoy surrendered the entire Spartan fleet at Pylos. However, these negotiations failed, and fighting resumed. Athens then won a decisive victory and the captured Spartan soldiers were taken back to Athens as prisoners of war.

Brasidas Marches to Amphipolis

The Athenian victory at Pylos gave them an important stronghold in the Peloponnese, and the Spartans knew they were in trouble. If they did not act quickly, the Athenians could send reinforcements and use Pylos as a base to run raids throughout the Peloponnese, as well as to house helots who decided to flee and defect to Athens. However, instead of retaliating at Pylos, the Spartans decided to copy the Athenians’ strategy and attack deep in their own territory where they might be least expecting it.

Under the command of the well-respected general Brasidas, the Spartans launched a large-scale attack in the northern Aegean. They were able to achieve considerable success, making it all the way to Amphipolis, one of Athen’s more important allies in the Aegean. However, in addition to winning territory by force, Brasidas was also able to win the hearts of the people. Many had grown tired of Athens’ thirst for power and aggression, and Brasidas’ moderate approach allowed him to win support from large swaths of the population without having to launch a military campaign. Interestingly, at this point, Sparta had freed helots throughout the Peloponnese to both stop them from running to the Athenians and also to make it easier to build their armies.

After Brasidas’ campaign, Cleon attempted to summon a force to retake the territory Brasidas had won, but political support for the Peloponnesian war was waning, and the treasuries were running low. As a result, he was not able to start his campaign until 421 BCE, and when he arrived near Amphipolis, he was met with a Spartan force that was much larger than his, as well as a population that was not interested in returning to a life governed by Athens. Cleon was killed during this campaign, which led to a dramatic change in the course of events in the Peloponnesian War.

Rjdeadly [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

The Peace of Nicias

After Cleon died, he was replaced by a man named Nicias, and he rose to power on the idea that he would sue for peace with Sparta. The plague that struck the city at the beginning of the Peloponnesian war, combined with the fact that a decisive victory appeared nowhere in sight, created an appetite for peace in Athens. By this point, Sparta had been suing for peace for some time, and when Nicias approached Spartan leadership, he was able to negotiate an end to this part of the conflict.

The peace treaty, known as the Peace of Nicias, was meant to establish peace between Athens and Sparta for fifty years, and it was designed to restore things to the way they were before the Peloponnesian war broke out. Some territory changed hands, and many of the lands conquered by Brasidas were returned to Athens, although some were able to maintain a level of political autonomy. Furthermore, the Peace of Nicias treaty stated that each side needed to impose the terms on its allies so as to prevent conflicts that could restart fighting between Athens and Sparta. However, this peace treaty was signed in 421 BCE, just ten years after the start of the 27-year Peloponnesian War, meaning it would also fail and fighting would soon resume.

Part 2: The Interlude

This next period of the Peloponnesian War, which took place between 421 BCE and 413 BCE, is often referred to at The Interlude. During this chapter of the conflict, there was little direct fighting between Athens and Sparta, but tensions remained high, and it was clear almost immediately that the Peace of Nicias would not last.

Argos and Corinth Collude

The first conflict to arise during The Interlude actually came from within the Peloponnesian League. The terms of the Peace of Nicias stipulated that both Athens and Sparta were responsible for containing their allies so as to prevent further conflict. However, this did not sit well with some of the more powerful city-states that were not Athens or Sparta, the most significant being Corinth.

Located between Athens and Sparta on the Isthmus of Corinth, the Corinthians had a powerful fleet and a vibrant economy, which meant they were often able to challenge Sparta for control of the Peloponnesian League. But when Sparta was put in charge of reigning in the Corinthians, this was seen as an affront to their sovereignty, and they reacted by reaching out to one of Sparta’s biggest enemies outside of Attica, Argos.

Karin Helene Pagter Duparc [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

One of the few major cities located on the Peloponnese that was not part of the Peloponnesian League, Argos had a long-standing rivalry with Sparta, but during The Interlude they had been subjected to a non-aggression pact with Sparta. They were going through a process of armament, which Corinth supported as a way to prepare for war with Sparta without making an outright declaration.

Argos, seeing this turn of events as a chance to flex its muscles, reached out to Athens for support, which it got, along with the support of a few other smaller city-states. However, this move cost the Argives the support of the Corinthians, who were not willing to make such an affront to their longtime allies on the Peloponnese.

All of this jockeying led to a confrontation between Sparta and Argos at Mantineia, a city in Arcadia just to the north of Sparta. Seeing this alliance as a threat to their sovereignty, the Spartans amassed a rather large force, around 9,000 hoplites according to Thucydides, and this allowed them to win a decisive battle that brought an end to the threat posed by Argos. However, when Sparta saw Athenians standing alongside the Argives on the battlefield, it became clear that Athens was not likely to honor the terms of the Peace of Nicias, an indication that the Peloponnesian War was not yet over. Thus, the Peace of Nicias treaty was broken from the start and, after several more failures, was formally abandoned in 414 BC. Thus, the Peloponnesian War resumed in its second stage.

Athens Invades Melos

An important component of the Peloponnesian War is Athenian imperial expansion. Emboldened by their role as the leader of the Delian alliance, the Athenian assembly was keen to find ways to expand its sphere of influence, and Melos, a tiny island state in the southern Aegean, was a perfect target, and it’s likely the Athenians saw its resistance from their control as stain on their reputation. When Athens decided to move, the superiority of its navy meant Melos stood little chance of resisting. It fell to Athens without much of a fight.

Kurzon [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

This event didn’t have much significance in the Peloponnesian War if we understand the conflict simply as a fight between Athens and Sparta. However, it does show how, despite the Peace of Nicias, Athens was not going to stop trying to grow, and, perhaps more importantly, it showed just how closely Athenians linked their empire with democracy. The idea was that if they did not expand, someone else would, and this would put their precious democracy at risk. In short, it’s better to be the rulers than the ruled. This philosophy, which was present in Athens before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, was now running rampant, and it helped provide justification for the Athenian expedition into Sicily, which played an important role in restarting the conflict between Athens and Sparta and also perhaps dooming Athens to defeat.

The Invasion of Sicily

Desperate to expand, but knowing that doing so on the Greek mainland would almost certainly lead to war with the Spartans, Athens began looking further afield for territories it could place under its control. Specifically, it began to look westward towards Sicily, an island in modern-day Italy that was at the time heavily settled by ethnic Greeks.

The main city on Sicily at the time was Syracuse, and the Athenians hoped to gather support for their campaign against Syracuse from both the non-aligned Greeks on the island as well as the native Sicilians. The leader in Athens at the time, Alcibiades, managed to convince the Athenian assembly that there was already an extensive support system waiting for them in Sicily, and that sailing there would lead to certain victory. He was successful, and in 415 BCE, he sailed west to Sicily with 100 ships and thousands of men.

However, it turned out the support promised to Alcibiades was not as certain as he had imagined. The Athenians attempted to gather this support after landing on the island, but in the time it took for them to do this, the Syracusans were able to organize their defenses and call together their armies, leaving the Athenian prospects for victory rather slim.

Athens in Turmoil

At this point in the Peloponnesian war, it’s important to recognize the political instability occurring within Athens. Factions were wreaking havoc on democracy, and new groups rose to power with the idea of exacting exact revenge on their predecessors.

A great example of this occurred during the Sicilian campaign. In short, the Athenian assembly sent word to Sicily calling Alcibiades back to Athens to face trial for religious crimes he may or may not have committed. However, instead of returning home to certain death, he fled to Sparta and alerted the Spartans of the Athenians’ attack on Sparta. Upon hearing this news, Sparta, along with Corinth, sent ships to help the Syracusans defend their city, a move that all but restarted the Peloponnesian War.

The attempted invasion of Sicily was a complete disaster for Athens. Almost the entire contingency sent to invade the city was destroyed, and several of the main commanders of the Athenian military died while trying to retreat, leaving Athens in a rather weak position, one that the Spartan would be all too keen to exploit.

Part 3: The Ionian War

The last part of the Peloponnesian War started in 412 BCE, a year after Athens’ failed campaign to Sicily, and it lasted until 404 BCE. It is sometimes referred to as the Ionian War because much of the fighting took place in or around Ionia, but it has also been referred to as the Decelean War. This name comes from the city of Decelea, which Sparta invaded in 412 BCE. However, instead of burning the city, Spartan leadership chose to set up a base in Decelea so that it would be easier to run raids into Attica. This, plus the Spartan decision to not require soldiers to return home each year for the harvest, allowed the Spartans to keep the pressure on Athens as it ran campaigns throughout its territories.

Sparta Attacks the Aegean

The base at Decelea meant that Athens could no longer rely on the territories throughout Attica to supply it with the supplies it needed. This meant Athens had to increase its tribute demands on its allies throughout the Aegean, which strained its relationship with the many of the members of the Delian League/Athenian Empire.

To take advantage of this, Sparta began sending envoys to these cities encouraging them to rebel against Athens, which many of them did. Furthermore, Syracuse, grateful for the help they received in defending their city, supplied ships and troops to help Sparta.

However, while this strategy was sound in logic, it ended up not leading to a decisive Spartan victory. Many of the city-states that had promised support to Sparta were slow to provide troops, and this meant Athens still had the advantage at sea. In 411 BCE, for example, the Athenians were able to win the Battle of Cynossema, and this stalled the Spartans’ advances into the Aegean for some time.

Athens Strikes Back

In 411 BCE, the Athenian democracy fell to a group of oligarchs known as The Four Hundred. Seeing that there was little hope for victory over Sparta, this group began trying to sue for peace, but the Spartans ignored them. Then, The Four Hundred lost control of Athens, surrendering to a much larger group of oligarchs knowns as “the 5,000.” But in the midst of all this, Alcibiades, who had previously defected to Sparta during the Syracuse campaign, had been trying to earn his way back into the good graces of the Athenian elite. He did this by putting together a fleet near Samos, an island in the Aegean, and fighting the Spartans.

His first encounter with the enemy came in 410 BCE at Cyzicus, which resulted in an Athenian rout of the Spartan fleet. This force continued to sail around the northern Aegean, driving out the Spartans wherever they could, and when Alcibiades returned to Athens in 407 BCE, he was welcomed as a hero. But he still had many enemies, and after being sent to campaign in Asia, a plot was hatched to have him killed. When Alcibiades learned of this, he abandoned his army and retreated into exile in Thrace until he was found and killed in 403 BCE.

The Peloponnesian War Comes to an End

This brief period of military success brought on by Alcibiades gave the Athenians a glimmer of hope that they could defeat the Spartans, but this was really just an illusion. The Spartan’s had managed to destroy most of the land in Attica, forcing people to flee to Athens, and this meant Athens was entirely dependent on its maritime trade for food and other supplies. The Spartan king at the time time, Lysander, saw this weakness and decided to change the Spartan strategy to focus on intensifying the siege of Athens.

At this point, Athens was receiving almost all of its grains from the Hellespont, also known as the Dardanelles. As a result, in 405 BCE, Lysander summoned his fleet and set out for this important part of the Athenian Empire. Seeing this as a major threat, the Athenians had no choice but to pursue Lysander. They followed the Spartans into this narrow stretch of water, and then the Spartans turned around and attacked, routing the fleet and capturing thousands of soldiers.

This victory left Athens without access to important staple crops, and because the treasuries had all but been depleted due to nearly 100 years of war (against both Persia and Sparta), there was little hope of regaining this territory and winning the war. As a result, Athens had no choice but to surrender, and in 404 BCE, the Peloponnesian War officially came to an end.

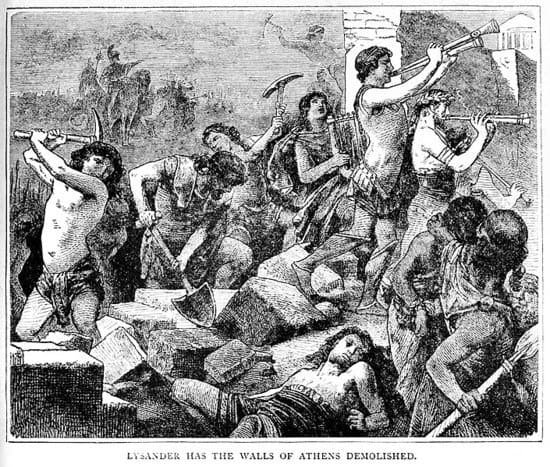

Aftermath of the War

When Athens surrendered in 404 BCE, it was clear that the Peloponnesian war had truly come to an end. Political instability within Athens had made it difficult for the government to function, its fleet had been destroyed, and its treasuries were empty. This meant Sparta and its allies were free to dictate the terms of peace. Thebes and Corinth wanted to burn it to the ground and enslave its people, but the Spartans rejected this notion. Although they had been enemies for years, Sparta recognized the contributions Athens had made to Greek culture and did not want to see it destroyed. Lysander, however, established a pro-Spartan oligarchy that installed a reign of terror in Athens.

However, perhaps more importantly, the Peloponnesian War dramatically changed the political structure of Ancient Greece. For one, the Athenian Empire was over. Sparta assumed the top position in Greece, and for the first time ever it formed an empire of its own, although this would not last more than a half century. Fighting would continue amongst the Greeks after the Peloponnesian war, and Sparta eventually fell to Thebes and its newly formed Boeotian League.

Yet perhaps the biggest impact of the Peloponnesian War was felt by the citizens of ancient Greece. The art and literature to come out of this time period spoke often of war weariness and of the horrors of such prolonged conflict, and even some of the philosophy, written by Socrates, reflected some of the inner conflicts people were facing as they tried to understand the purpose and meaning of so much bloodshed. Because of this, as well as the role the conflict had in shaping Greek politics, it’s easy to see why the Peloponnesian War played such an important role in the history of Ancient Greece.

The conquest of ancient Greece by Phillip of Macedon and the rise of his son, Alexander (the Great) were largely predicated on the conditions following the Peloponnesian War. This is due to the fact that the destruction from the Peloponnesian War weakened and divided the Greeks for years to come, eventually allowing the Macedonians an opportunity to conquer them in the mid-4th century BCE.

Conclusion

In many ways, the Peloponnesian War marked the beginning of the end for both Athens and Sparta in terms of political autonomy and imperial dominance. The Peloponnesian War marked the dramatic end to the fifth century BC and the golden age of Greece.

During the 4th century, the Macedonians would organize under Philip II, and then Alexander the Great, and bring nearly all of ancient Greece under its control, as well as parts of Asia and Africa. Shortly thereafter, the Romans began flexing their muscles throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Despite losing to Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, Athens continued to be an important cultural and economic center throughout Roman times, and it is the capital of the modern nation of Greece. Sparta, on the other hand, despite never being conquered by the Macedonians, ceased to have much influence on the geopolitics of ancient Greece, Europe, or Asia after the 3rd century BCE.

Brastite at the English language Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

The Peloponnesian War was soon followed by the Corinthian War (394–386 BC), which, although it ended inconclusively, helped Athens regain some of its former greatness.

It’s true we can look at the Peloponnesian War today and ask “why?” But when we consider it in the context of the time, it’s clear how Sparta felt threatened by Athens and how Athens felt it necessary to expand. But no matter which way we look at, this tremendous conflict between two of the most powerful cities of the ancient world played an important role in writing ancient history and in shaping the world we call home today.

Contents

READ MORE: The Battle of Yarmouk

Bibliography

Bury, J. B, and Russell Meiggs. A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great. London: Macmillan, 1956

Feetham, Richard, ed. Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War. Vol. 1. Dent, 1903.

Kagan, Donald, and Bill Wallace. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003.

Pritchett, W. Kendrick. The Greek State of War The University of California Press, 1971

Lazenby, John F. The Defence of Greece: 490-479 BC. Aris & Phillips, 1993.

Sage, Michael. Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook. Routledge, 2003

Tritle, Lawrence A. A New History of the Peloponnesian War. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.