Augustus Caesar was the first emperor of the Roman Empire and is famous not only for that fact but also because of the impressive groundwork he laid for all future emperors. Beyond this, he was also a very capable administrator of the Roman state, learning much from his advisors like Marcus Agrippa, as well as his adoptive father and his great-uncle, Julius Caesar.

Table of Contents

What Made Augustus Caesar Special?

Following in the latter’s footsteps, Augustus Caesar – who was in fact born Gaius Octavius (and known as “Octavian”) – won sole power over the Roman state after a long and bloody civil war against an opposing claimant (just as Julius Caesar had). Unlike his uncle, however, Augustus managed to cement and secure his position from any present and future rivals.

In doing so, he set the Roman Empire onto a course that saw its political ideology and infrastructure transform from (an albeit decaying) republic, to a monarchy (officially named the principate), with the emperor (or “princeps”) at its head.

Before any of these events, he had been born in Rome in September 63 BC, into the equestrian (lower aristocratic) branch of the gens (clan or “house of”) Octavia. His father died when he was four and was thereafter raised mostly by his grandmother Julia – who was the sister of Julius Caesar.

As he reached manhood, he became embroiled in the chaotic political events that were unfolding between his great uncle Julius Caesar and the opponents who faced him. Out of the turmoil that ensued, Octavian the boy would become Augustus the ruler of the Roman world.

READ MORE: The Complete Roman Empire Timeline: Dates of Battles, Emperors, and Events

Augustus’s Significance for Roman History

To understand Augustus Caesar then and the significance he holds for the entirety of Roman History, it is important to first delve into this process of seismic change that the Roman Empire experienced – especially Augustus’s role in it.

For this (and the events of his actual reign), we are fortunate to have a relative wealth of contemporary sources to analyze, quite unlike much of what follows in the principate, as well as what had preceded it in the republic.

Perhaps as part of a conscious effort by contemporaries to memorialize this transformative period of history, there are many different sources we can turn to that provide relatively complete narratives of the events. These include Cassius Dio, Tacitus, and Suetonius, as well as the inscriptions and monuments across the empire that marked his reign – none more so, than the famous Res Gestae.

The Res Gestae and Augustus’s Golden Age

The Res Gestae was Augustus’s own obituary to future readers, engraved on stone throughout the empire. This extraordinary piece of epigraphic history was found on walls from Rome to Turkey and testifies to the exploits of Augustus and the various ways in which he augmented the power and grandeur of Rome and its empire.

And indeed, under Augustus, the boundaries of the empire were expanded considerably, just as there was an outpouring of poetry and literature, as Rome experienced a “Golden Age”. What made this felicitous period seem all the more exceptional and the emergence of an “emperor” all the more necessary, were the tumultuous events that preceded it.

What Role Did Julius Caesar Play in Augustus’s Rise?

As has been already alluded to, the famous figure of Julius Caesar was also central to the rise of Augustus as emperor and in many ways created the foundation upon which the principate was to emerge.

The Late Republic

Julius Caesar had entered the political scene of the Roman Republic during a period where overly ambitious generals began to vie for power quite routinely against each other. As Rome continued to wage larger and larger wars against its enemies, opportunities grew for successful generals to increase their power and standing in the political scene more than they had previously been able to.

Whereas the Roman Republic “of old” was supposed to revolve around a collective ethos of patriotism, the “Late Republic” witnessed violent civil discords between opposing generals.

In 83 BC this led to the civil war of Marius and Sulla, who were both prodigiously decorated generals who had won glorious victories against Rome’s enemies; now turned against each other.

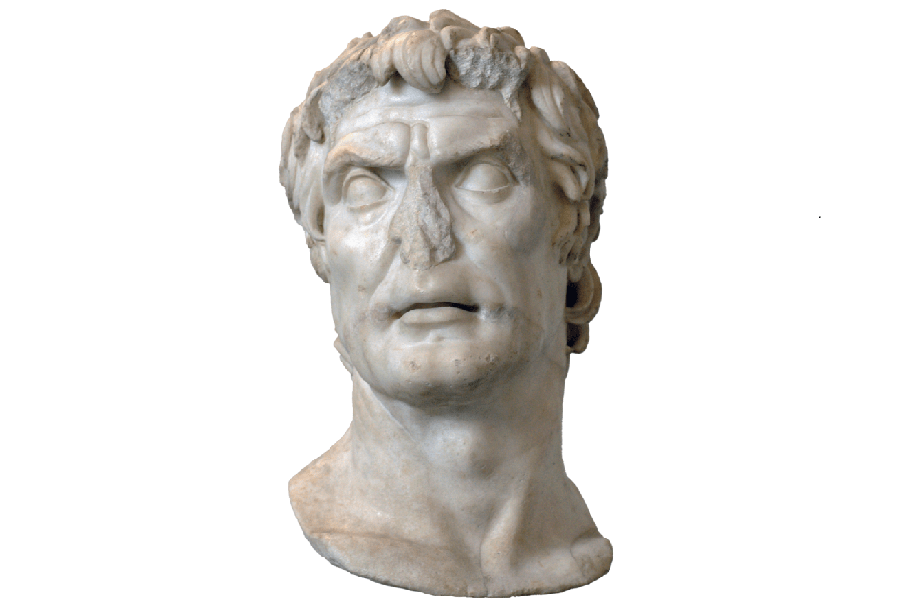

In the aftermath of this bloody and infamous civil war, wherein Lucius Sulla was victorious (and ruthless against the vanquished side), Julius Caesar began to gain some prominence as a populist politician (in opposition to the more conservative aristocracy). He was in fact considered lucky to have been left alive at all because he was quite closely related to Marius himself.

The First Triumvirate and Julius Caesar’s Civil War

During Julius Caesar’s rise to power, he initially aligned himself with his political opponents, in order so that they could all stay in their military positions and augment their influence. This was called the First Triumvirate and consisted of Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey”), and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Whilst this arrangement worked initially and kept these generals and politicians at peace with each other, it fell apart at the death of Crassus (who was always seen as a stabilizing figure).

Soon after his death, relations deteriorated between Pompey and Caesar and another civil war like Marius and Sulla’s resulted in the death of Pompey and the appointment of Caesar as “Dictator for life”.

The position of Imperator (“Dictator”) had existed previously – and was taken up by Sulla after his success in the civil war – however, it was only supposed to be a temporary position. Caesar had instead decided he was to remain in the position for life, placing absolute power in his hands permanently.

The Assassination of Julius Caesar

Although Caesar refused to be called “King” – as the label held many negative connotations in Republican Rome – he still acted with absolute power, which enraged many contemporary senators. As a result, a plot was hatched to assassinate him that had the backing of large portions of the senate.

On the “Ides of March” (March 15th) 44 BC, Julius Caesar was murdered during a meeting of the senate at the theater of his old rival Pompey. At least 60 senators were involved, even one of Caesar’s favorites called Marcus Junius Brutus, and he was stabbed 23 times by different conspirators.

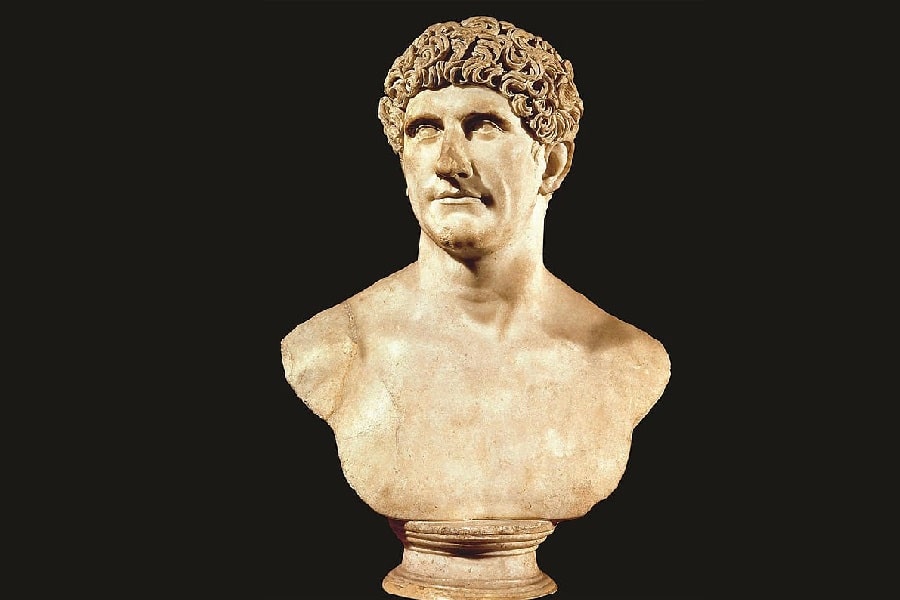

In the wake of this momentous event, the conspirators had expected things to go back to normal and for Rome to remain a republican state. However, Caesar had left an indelible mark on Roman politics and had been supported, amongst others, by his trusty general Mark Antony and his adopted heir, Gaius Octavius – the boy who was to become Augustus himself.

Whilst the conspirators who killed Caesar had some political clout in Rome itself, figures like Antony and Octavian possessed real power with soldiers and wealth.

The Aftermath of Caesar’s Death and the Extermination of the Assassins

The conspirators of Caesar’s murder were neither completely unified nor militarily backed in their efforts. As such, it wasn’t long before they all fled the capital and escaped to other parts of the empire, to either hide or raise a rebellion against the forces they knew were set on pursuing them.

These forces were Octavian and Mark Antony. Whilst Mark Antony had been by Caesar’s side through much of his military and political life, Caesar had adopted his great-nephew Octavian as his heir shortly before his death. As was the way of life in the Late Republic these two successors of Caesar were destined to eventually start a civil war with each other.

However, they first went about the pursuit and extermination of the conspirators who had murdered Julius Caesar, which amounted to a civil war in itself as well. After the battle of Philippi in 42 BC, the conspirators were for the most part defeated, meaning it was only a matter of time before these two heavyweights turned against each other.

The Second Triumvirate and Fulvia’s War

Whilst Octavian had been allied with Antony since the death of Julius Caesar – and they formed their own “Second Triumvirate” (with Marcus Lepidus) – it seemed clear that both wanted to acquire the position of absolute power Julius Caesar had established after his defeat of Pompey.

Initially, they partitioned the empire into three divisions, with Antony taking control of the east (and Gaul) and Octavian, Italy, and most of Spain, with Lepidus, only taking control of North Africa. Things, however, began to degenerate quickly when Antony’s wife Fulvia opposed some aggressive land grants that Octavian had initiated, in order to settle veterans of Caesar’s legions.

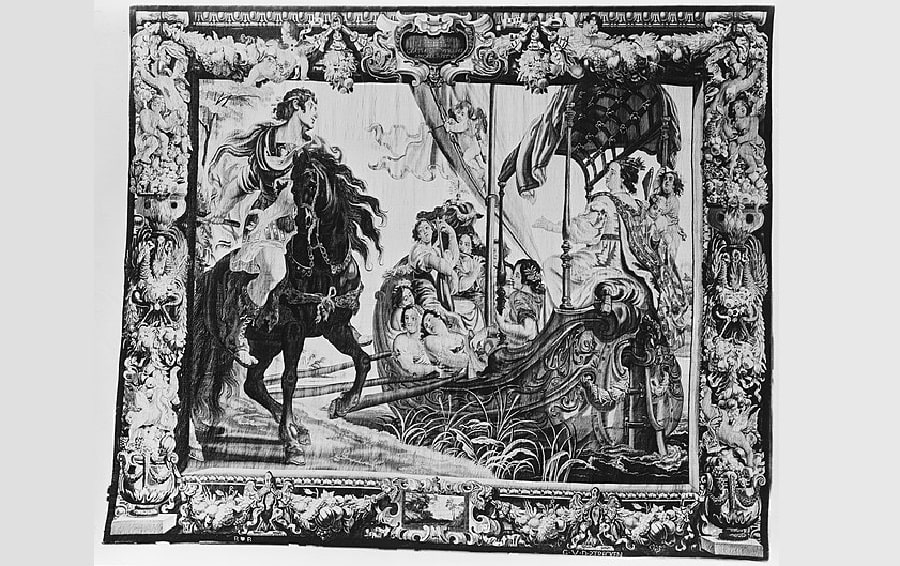

Fulvia at the time was a prominent political player in Rome, even though she was seemingly disregarded by Antony himself, who had engaged in a union of sorts with the famous Cleopatra, fathering twins with her.

Fulvia’s intransigence turned into another (albeit brief) civil war, wherein Fulvia and Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius marched on Rome, to “liberate” its people from Octavian. They were swiftly forced to retreat by the armies of Octavian and Lepidus, whilst Antony seemed to watch on and do nothing from the east.

Antony in the East and Octavian in the West

Although Antony eventually came to Italy to confront Octavian and Lepidus, things were for the time being, quite quickly resolved with the Treaty of Brundisium in 40 BC.

This cemented the agreements previously made by the Second Triumvirate, but now gave Augustus control of most of the west of the empire (except Lepidus’s North Africa), whilst Antony returned to his portion in the East.

This was complimented by the marriage of Antony and Octavian’s sister Octavia, as Fulvia was divorced and died soon after in Greece.

Antony’s War with Parthia and Octavian’s War with Sextus Pompey

Before long Antony instigated a war with Rome’s perennial enemy to the east Parthia – a foe that Julius Caesar was reported to have had his eye upon as well.

Whilst this was initially successful and territory was added to the Roman sphere of influence, Antony became complacent with Cleopatra in Egypt (much to the concern of Octavian and his sister Octavia), leading to a reciprocal invasion into Roman territory by Parthia.

Whilst this struggle in the east was ongoing, Octavian was dealing with Sextus Pompey, the son of Julius Caesar’s old rival Pompey. He had taken control of Sicily and Sardinia with a powerful fleet and had harried Rome’s waters and shipping for some time, to the consternation of both Octavian and Lepidus.

Eventually, he was defeated, but not before his behavior had caused a rift to grow between Antony and Octavian, as the former repeatedly asked for assistance from the latter in dealing with Parthia.

Moreover, when Sextus Pompey was defeated, it wasn’t long before Lepidus saw his chance for advancement and attempted to take control of Sicily and Sardinia. His plans were quickly thwarted, and he was forced by Augustus to step down from his position as triumvir, bringing that tripartite agreement to an end.

Octavian’s War with Antony

When Lepidus was moved out of position by Octavian, who now took sole charge of the western half of the empire, relations soon began to fall apart between him and Antony. Slander was thrown by both sides, as Octavian accused Antony of debauching himself with the foreign queen Cleopatra, and Antony accused Octavian of forging the will of Julius Caesar that named him an heir.

The real split occurred when Antony celebrated a triumph for his successful invasion and conquest of Armenia, after which he donated the eastern half of the Roman Empire to Cleopatra and her children. Furthermore, he named Caesarion (the child Cleopatra had had with Julius Caesar) as Julius Caesar’s true heir.

In the midst of this, Octavia was divorced by Antony (to the surprise of no one) and the war was declared in 32 BC – specifically against Cleopatra and her usurping children. Octavian’s general and trusted advisor Marcus Agrippa moved first and captured the Greek city of Methone, after which Cyrenaica and Greece turned to Octavian’s side.

Forced to act, Cleopatra’s and Antony’s Navy met the Roman fleet – again commanded by Agrippa – off the Greek coast at Actium in 31 BC. Here they were thoroughly defeated by Octavian’s side and they subsequently fled to Egypt, where they committed suicide in dramatic fashion.

Augustus’s “Restoration of the Republic”

The way in which Octavian managed to hold onto the absolute power of the Roman state was much more tactful than the methods tried by Julius Caesar. In a series of staged actions and events, Octavian – soon to be named Augustus – “restored the [Roman] republic.”

Returning the Roman State to Stability

By the time of Octavian’s victory at Actium, the Roman world had experienced a relentless series of civil wars and recurrent “proscriptions” where political opponents would be sought out and executed, by both sides of the conflicts. Indeed, a state of lawlessness had for the most part proliferated.

As a result, it was essential and desirable for both the senate and Octavian, for things to return to some level of normalcy. Accordingly, Octavian immediately began to court those new members of the senate and aristocracy who had survived the civil wars now past.

In the first return to some level of familiarity, both Octavian and his second-in-command Agrippa were made consuls; positions to legitimate (in appearance) the vast power and resources they had at their disposal.

The Settlement of 27 BC

Next came the famous Settlement of 27 BC wherein Octavian returned full power to the senate and surrendered his control of the provinces and their armies that he had controlled since the days of Julius Caesar.

Many believe this “stepping back” from Octavian was a carefully calculated ploy, as the senate in their clearly inferior and impotent position immediately offered Octavian back these powers and areas of control. Not only was Octavian unrivaled in his power, but the Roman aristocracy was weary of the internecine civil wars that had rocked it in the past century. A strong and unified force was needed in the state.

As such, they bestowed on Octavian all of the powers that essentially made him a monarch and granted him the titles “Augustus” (which possessed pious and divine connotations) and “princeps” (meaning “first/best citizen” – and where the term “principate” derives from).

This staged act had the dual purpose of keeping Octavian – now Augustus – in power, able to keep stability in the state, and it gave off the (albeit spurious) appearance that it was the senate who were granting these extraordinary powers. For all intents and purposes, the Republic appeared to carry on, with its “princeps” steering it clear of the dangers it had experienced over the past century.

Further Powers Granted in the Second Settlement of 23 BC

It gradually became clear underneath this façade of continuity, that things had completely changed in the Roman state. As such, there was, especially at this early stage a certain amount of friction caused by such controversies, as it was reported that Augustus wanted to ensure that the principate would endure beyond his death.

As such, he seemed to groom his nephew Marcellus to follow in his footsteps and become the next princeps. This caused some concern, on top of the fact that Augustus up until 23 BC had held onto the consulship continuously, depriving other aspiring senators of taking up the position.

As in 27 BC, Augustus had to act tactfully and ensure that the appearance of republican propriety was maintained. Accordingly, he gave up the consulship in exchange for proconsular power over the provinces which possessed the most troops, which superseded that of any other consul or proconsul, known as “imperium maius”.

This meant that Augustus’s imperium was superior to anybody else’s, always giving him the final say. Whilst it was supposed to be granted for 10 years, it is unclear at this stage whether anybody really thought his predominance over the state was ever going to be seriously challenged.

Moreover, along with the granting of imperium maius, he was also given the full powers of a tribune and censor, giving him complete control over the culture of Roman society. He, therefore, became, not only its military and political savior but its cultural bulwark and defender as well. Power and prestige were now truly centered on one person.

Caesar in Power

Whilst in power, it was important that he was able to maintain the peace and stability that the Roman world had been lacking for so long. As well as therefore shoring up the empire’s defenses and considering where to invade next, Augustus went about promoting his own position and this new “golden age”.

Augustus’s Correction of the Coinage

One of the many things that Augustus set about fixing in the Roman state was the sorry state that the coinage had fallen into after such a long period of political turbulence. By the time he had taken power, it was really only the silver denarius that was in proper circulation.

This made it difficult to exchange wares and resources that were valued at less than a denarius, or considerably more. As such, Augustus ensured in the late 20s BC that 7 denominations of coinage would be struck, in order to help facilitate efficient and effective trade throughout the empire.

On this coinage, he also embodied many of the virtues and messages of propaganda that he wished to promote and propagate about his new rule. These focused on patriotic and traditional messages, further enforcing the republican façade that his “restoration” tried so hard to maintain.

The Patronage of Poets

As part of Augustus’s “golden age” and the propaganda campaign that vitalized it, Augustus was careful to patronize a coterie of different poets and writers. These included people such as Virgil, Horace, and Ovid, all of whom wrote enthusiastically about the new age into which the Roman world had emerged into.

It was through this agenda that Virgil wrote his canonical Roman epic, the Aeneid, wherein the origins of the Roman state were tied to the Trojan hero Aeneas, and the future glory of Rome was foretold and promised under the stewardship of the great Augustus.

During this period, Horace also wrote many of his Odes, some of which alluded to the present and future divinity of Augustus as helmsman of the Roman state. Throughout all of these works was a spirit of optimism and felicity about the new path Augustus had set the Roman world on.

Did Augustus Add More Territory to the Roman Empire?

Yes, Augustus is remarkably seen as one of the greatest expanders of the empire in its entire history – even though the fall of Rome did not occur until 476 AD!

He also monopolized the celebration of the empire’s military “triumphs” for the princeps exclusively, which had previously been held in honor of whichever victorious general returned to Rome from a successful campaign or battle.

Moreover, he also attached the title “imperator” (where we derive the term “emperor”) onto his own name, which connoted a victorious general. Henceforth “Imperator Augustus” was to be forever associated with victory, not only abroad in military campaigns, but at home as the victorious savior of the republic.

The Empire’s Expansion After Augustus’s Civil War with Antony

Whereas Egypt had previously been more of a vassal state before Augustus’s war with Mark Antony, it was incorporated into the empire properly after the latter’s defeat. This transformed the economy of the Roman world, as Egypt became the “breadbasket of the empire”, exporting millions of tons of wheat to other Roman provinces.

This addition to the empire was soon followed by the annexation of Galatia (modern-day Turkey) in 25 BC after its ruler Amyntas was killed by an avenging widow. In 19 BC, the rebellious tribes of modern-day Spain and Portugal were finally defeated, and their lands were incorporated into Hispania and Lusitania.

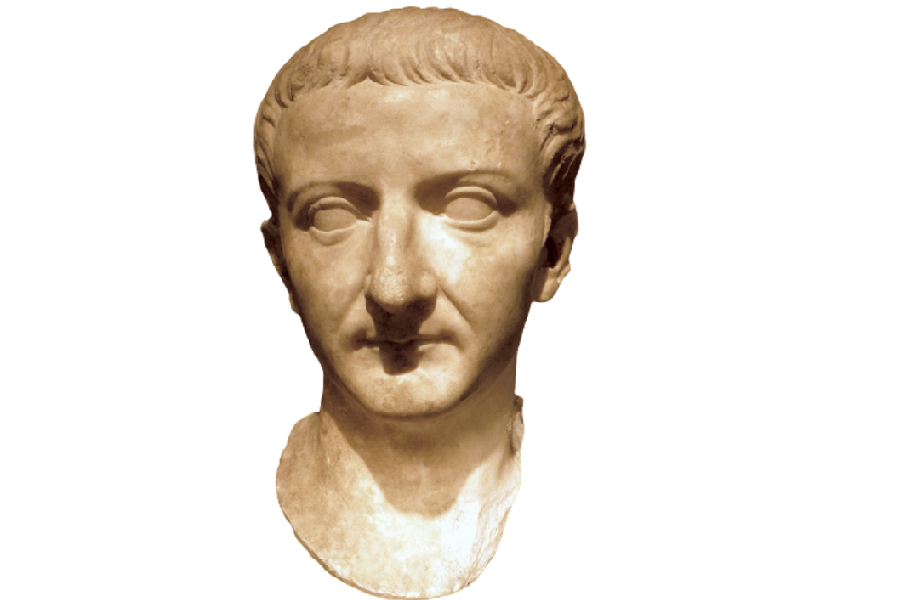

This was to be followed by Noricum (modern Switzerland) in 16 BC, which provided a territorial buffer against enemy lands further north. For many of these conquests and campaigns, Augustus delegated command to a series of his chosen relatives and generals, namely, Drusus, Marcellus, Agrippa, and Tiberius.

Augustus and His Generals

Rome continued to be successful in its conquests under the leadership of these chosen generals, as Tiberius conquered parts of Illyricum in 12 BC and Drusus began moving across the Rhine in 9 BC. Here the latter met his end, leaving a lasting legacy of expectation and prestige for future favorites to try to match.

His legacy, however, also caused some friction that Augustus apparently had to confront. Due to his military exploits, Drusus was very popular with the army and shortly before his death had written to Tiberius – Augustus’s stepson – to complain of the emperor Augustus’s method of ruling.

Three years before this, Augustus had already begun to alienate himself from Tiberius by forcing Tiberius to divorce his wife Vispania, and marry Augustus’s daughter, Julia. Perhaps still disgruntled because of his forced divorce, or too distraught at the death of Drusus, his brother, Tiberius retired to Rhodes in 6 BC and removed himself from the political scene for ten years.

Opposition in Augustus’s Reign

Inevitably, Augustus’s reign of more than 40 years, wherein the machinery of state was focused exclusively around one person, met some opposition and resentment, especially from those “republicans” who did not like to see the way the Roman world had changed.

It must be said that for the most part, people seemed to have been quite happy with the peace, stability, and prosperity that Augustus brought to the empire. Additionally, the campaigns that his generals conducted (and Augustus celebrated) were almost all very successful; except the battle at the Teutoburg Forest, which we will explore more below.

Moreover, the different settlements that Augustus made in 27 BC and 23 BC, as well as some additional ones that followed thereafter, have been seen as Augustus’s wrestling with some of his opponents and maintenance of the slightly precarious status quo.

Attempts on Augustus’s Life

As is the case with almost all Roman emperors, the sources tell us that there were a number of conspiracies against Augustus’s life. Modern historians have however suggested that this was a gross exaggeration and only point to one conspiracy – in the late 20s BC – as the only serious threat.

This was planned by two politicians named Caepio and Murena who had seemingly gotten fed up with Augustus’s monopolization of the state machinery. The events leading up to the conspiracy appear to be directly linked to Augustus’s second settlement of 23 BC, where he gave up the consulship, but held onto its power and privileges.

The Primus Trial and the Conspiracy Against Augustus

Around this time Augustus had become seriously ill and talk of what would follow his death had spread. He had written a will that many believed to have named his heir for the principate, which would have been a flagrant abuse of the power that had been “granted” to him by the senate (although they later seemed to renege on such protests).

Augustus in fact recovered from his illness, and to assuage worried senators, was willing to read out his will in the senate house. This, however, seemed not to be enough to calm the fears of some and in 23 or 22 BC a governor in the province of Thrace called Primus was put on trial for improper conduct.

Augustus intervened directly in this case, seemingly hell-bent on having him prosecuted (and later executed). As a result of such blatant imperious involvement in the affairs of the state, the politicians Caepio and Murena apparently plotted an attempt on Augustus’s life.

Whilst the sources are quite ambiguous about its exact events, we know that it failed rather quickly and that both were condemned by the senate. Murena fled and Caepio was executed (after also trying to escape).

Why Were There So Few Attempts on Augustus’s Life?

Whilst this conspiracy of Murena and Caepio is linked to a part of Augustus’s reign commonly called a “crisis,” in hindsight it seems as though opposition to Augustus was neither unified nor much of a threat – at this point, and throughout his reign.

And indeed, this seems reflected throughout the sources, and the reasons for such a lack of opposition, lie, in the main part, in the events that led up to Augustus’s “accession.” Not only had Augustus brought peace and stability to a state racked by endless civil wars, but the aristocracy itself had grown weary, and many of Augustus’s enemies had been killed or soundly discouraged from further rebellion.

As alluded to above, there are other reported conspiracies mentioned in the sources, but all of them seem so poorly planned to warrant any discussion in modern analyses. For the most part, it seems as though Augustus ruled well, and without much serious opposition.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Effects It Had on Augustan Policy

Augustus’s time in power was constituted by constant expansions of Roman territory and indeed the empire expanded under him more than under any subsequent ruler. To go with the acquisitions of Spain, Egypt, and parts of central Europe along the Rhine and Danube, he also managed to procure parts of the Middle East including Judaea, in 6 AD.

However, in 9 AD, disaster struck in the lands of Germania, in the Teutoburg forest, where three entire legions of Roman soldiers were lost. After this, Rome’s attitude to continuous expansion changed forever.

Background to the Disaster

Around the time when Drusus died in Germania in 9 BC, Rome confiscated the sons of one of the leading German chieftains, named Segimerus. As was the custom, these two sons – Arminius and Flavus – were to be raised in Rome and would learn the customs and culture of their conqueror.

This had the dual effect of keeping client chiefs and kings like Segimerus in line and also helped generate loyal barbarians who could serve in Rome’s auxiliary regiments. This was the plan anyway.

By 4 AD, the peace between the Romans and the German barbarians beyond the Rhine had broken and Tiberius (who had now returned from Rhodes after being named Augustus’s heir) had been sent in to pacify the region. In this campaign, Tiberius managed to push through to the river Weser, after defeating the Cananefates, Chatti, and Bructeri in decisive victories.

To oppose another threat (the Marcomanni, under Maroboduus) a massive force of more than 100,000 men was assembled in 6 AD and sent deep into Germania under the Legatus Saturnius. Later that year, the command was handed over to a respected politician called Varus, who was the incoming governor of the now “pacified” province of Germania.

The Varian Disaster (A.K.A The Battle of Teutoberg Forest)

As Varus was to find out, the province was far from pacified. Leading up to the disaster, Arminius, the son of the chieftain Segimerus, had been stationed in Germania, commanding a troop of auxiliary soldiers. Unbeknownst to his Roman masters, Arminius had allied himself with a number of German tribes and conspired to throw the Romans out of their homeland.

Accordingly, in 9 AD, whilst the majority of Saturnius’s original force of more than 100,000 men were with Tiberius in Illyricum, putting down an uprising there, Arminius found the perfect time to strike.

Whilst Varus was moving his three remaining legions to his summer camp, Arminius convinced him that there was a rebellion nearby that needed his attention. Familiar with Arminius, and convinced of his loyalty, Varus followed his lead, deep into a dense forest known as the Teutoburg forest.

Here, all three legions, along with Varus himself, were ambushed and exterminated by an alliance of Germanic tribes, never to be seen again.

READ MORE: Roman Wars

The Effect of the Disaster on Roman Policy

Upon finding out about the annihilation of these legions, Augustus is said to have shouted “Varus, bring me back my legions!.” Yet Augustus’s laments would not bring back these soldiers and Rome’s north-eastern front was thrown into turmoil.

Tiberius was quickly sent to bring some stability, but by now it was clear that Germania could not be so easily conquered, if at all. Whilst there was some confrontation between Tiberius’s troops and those of Arminius’s new coalition, it was not until after the death of Augustus, that a proper campaign against them got underway.

Nevertheless, the region of Germania was never conquered and Rome’s seemingly unending expansion ceased. Whilst Claudius, Trajan, and some later emperors added some (relatively unimportant) provinces, the rapid expansion experienced under Augustus was stopped dead in its tracks along with Varus and his three legions.

Augustus’s Death and Legacy

In 14 AD, having held sway over the Roman Empire for more than 40 years, Augustus died in Nola, Italy, the same place that his father had. Whilst this was a momentous event that no doubt caused some shockwaves throughout the Roman world, his succession was well prepared for, even though he was not officially a monarch.

There had however been a catalog of potential heirs named throughout Augustus’s reign, many of which had died early deaths, until Tiberius was finally picked in 4 AD. Upon Augustus’s death then, Tiberius “took up the purple” and received Augustus’s wealth and resources – whilst his titles were effectively transferred to him by the senate, on top of the titles Tiberius had already shared with Augustus previously.

The principate was therefore to endure, still masked in its republican guise, with the senate “officially” being the bestowers of power. Tiberius continued on as Augustus had, feigning subservience to the senate, and masquerading as the “first among equals”.

Such a facade Augustus had set in motion, never again for the Romans to return to a republic. There were moments when the principate seemed to hang by a thread, especially at the deaths of Caligula and Nero, but things had so irreversibly changed that the idea of a republic soon became completely alien to Roman society. Augustus had forced Rome to rely on a central figurehead who could ensure peace and stability.

For all this, however, the Roman Empire curiously never really had an emperor to match its first, although Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, or Constantine would come quite close. Certainly, no other emperor expanded the empire’s boundaries further, as well as the fact that no age’s literature ever really matched that of Augustus’s “golden age.”