King Herod is a name that might be vaguely familiar to the majority of us because of mentions in the Bible and in connection with Jesus Christ. But how many of us are aware of the actual man that existed beyond that forbidding figure, the man who was called King Herod the Great? Who was the real King of Judea, a man who rose to that position through incredible grit and determination? Was he a tyrant or a great builder and hero? Was he a friend or foe of the Roman Empire? What was the deal with his numerous wives and sons and the succession crisis he left behind at his death? Let us try and explore the man behind the tales.

Table of Contents

Who Was King Herod?

In the first century BCE, King Herod, also known as Herod the Great, was the ruler of the Roman province of Judea. Accounts seem to disagree on whether Herod was an extraordinary ruler or a terrible one. The most reasonable assumption would be that he was a bit of both. After all, throughout history, it has been the kings and emperors with the most terrible conquests and brutal victories under their belt who have come to be known by the suffix ‘the great.’

There seems to be a strange dichotomy to the perception of Herod that has existed all these centuries. As a tyrannical king who was cruel not only to his subjects but his own family members, he is reviled. He is also known as the great builder, who helped construct some of the greatest temples and monuments in the Middle East today and improved the lifestyle of his people due to his great interest in architecture and design, and the remnants of his reign are admired to this day.

Certainly, he navigated his kingdom through some very treacherous political climates and helped build a flourishing society over the roughly 30 years of his rule. He managed to court the favor of the Roman Empire while still holding on to his own and his people’s Jewish beliefs.

Economically, there are mixed interpretations of whether Judea prospered during his reign or not. His extensive building projects are dismissed as being vanity projects, but there is no denying that they are great monuments that still stand as proof of the greatness of this old Roman province. His people were heavily taxed for these projects, but they also provided large-scale employment for many. Thus, King Herod is a controversial figure to modern scholars.

What Was He Known For?

The story that Herod is mostly known for today is believed by most historians now to have been fiction rather than fact. Herod has gone down in the popular imagination as the cruel and vengeful monster who so feared the future influence and power of baby Jesus that he decided to have the infant killed. As a result of this decision, he ordered the deaths of all the children in Bethlehem, a slaughter that baby Jesus escaped due to the flight of his parents from Bethlehem.

While this may not have been true, it does not mean that Herod was a kind and benevolent king either. He may not have committed the monstrous deed he has become known for, but he is also the man who executed one of his wives and at least three of his own children. Historians conjecture that this event may have been the starting point where King Herod’s descent into tyranny began.

False Worshiper?

Modern historians comment that King Herod may have been the only person in old Jewish history who was disliked not only by the Christians but also by Jews themselves for his tyrannical and cruel reign.

In Antiquities of the Jews, the 20-volume complete history of the Jews, written by Flavius Josephus, there is mention of how and why the Jews disliked Herod. Josephus wrote that while Herod attempted to conform to Jewish law at times. He was still much more invested in keeping his non-Jewish and Roman citizens happy and was believed to favor them over subjects who practiced the Jewish religion. He introduced many foreign kinds of entertainment and built a golden eagle outside the Temple of Jerusalem to symbolize the Roman Legion.

For many Jews, this was simply another indication that King Herod was a stooge of the Roman empire who had placed him on the throne of Judea despite his non-Jewish background and origins.

Herod himself was from Edom, an ancient kingdom located in what is now Israel and Jordan. This, along with his infamous murders of his family members and the excesses of the Herodian Dynasty, has given rise to questions about Herod’s religion and belief system.

Whether Herod was a practicing Jew is not clear, but he did seem to respect traditional Jewish practices in public life. He minted coins that did not feature human images and employed priests for the construction of the Second Temple. In addition to this, several ritual baths, used for purification purposes, were found in his palaces, hinting that this was one custom he did follow in private life.

Background and Origins

To get a complete picture of King Herod, it is necessary to know how Herod’s reign came about and who he really was before that. Herod belonged to an important Idumaean family, the Idumaeans being the successors of the Edomites. Most converted to Judaism when the Hasmonean Jewish king John Hyrcanus I conquered the area. Thus, it seems that Herod considered himself a Jew even if most of his detractors and opponents did not believe he had a claim on Jewish cultures of any kind.

Herod was the son of a man called Antipater and an Arab princess from Petra called Cypros and was born in about 72 BCE. His family had a history of being on good terms with powerful Romans, from Pompey and Julius Caesar to Mark Antony and Augustus. King Hyrcanus II appointed Antipater as the Chief Minister of Judea in 47 BCE, and Herod was in turn made Governor of Galilee. Herod built up friendships and allies among the Romans, and Mark Antony appointed Herod and his elder brother Phasael as Roman tetrarchs to support Hyrcanus II.

Antigonus of the Hasmonean Dynasty rose in rebellion against the king and took Judea from him. Phasael died in the ensuing crisis, but Herod fled to Rome to ask for help to retrieve Judea. The Romans, invested in conquering and keeping hold of Judea, named him King of the Jews and gave him aid in either 40 or 39 BCE.

Herod won the campaign against Antigonus and was given the hand of Mariamne, the granddaughter of Hyrcanus II, in marriage. Since Herod already had a wife and son, Doris and Antipater, he sent them away for the sake of this royal marriage to further his ambitions. Hyrcanus did not have any male heirs.

Antigonus was finally defeated in 37 BCE and sent to Mark Antony for execution, and Herod took the throne for himself. Thus ended the Hasmonean Dynasty and began the Herodian Dynasty.

The King of Judea

Herod was named the Jewish king by the Romans after Herod sought their aid in defeating and overthrowing Antigonus. With Herod’s new age of Judea began. It had previously been ruled by the Hasmoneans. They were autonomous for the most part, although after the conquest of Judea by Pompey they did acknowledge the might of the Romans.

Herod, however, was named the King of Judea by the Roman Senate and as such was directly under the overlordship of Rome. Officially, he may have been called an allied king, but he was very much a vassal to the Roman Empire and he was meant to rule and work for the greater glory of the Romans. For this reason, Herod had many opponents, not least of whom were his own Jewish subjects.

Rise To Power and Herod’s Reign

King Herod’s reign began with a victory in Jerusalem, achieved with the aid of Mark Antony. But his actual rule in Judea was not off to a great start. Herod executed many of Antigonus’ supporters, including several of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish elders who would in later years come to be known as the rabbi. The Hasmoneans were very unhappy to be overthrown, as one may assume, and Herod’s mother-in-law Alexandra was already plotting.

Antony had married Cleopatra just that year, and the Egyptian queen was a friend of Alexandra’s. Knowing that Cleopatra wielded great influence over her husband, Alexandra asked her to help make Mariamne’s brother Aristobulus III the High Priest. This was a position that was usually claimed by the Hasmonean kings, but the one Herod did not qualify for because of his Idumaean blood and background.

Cleopatra agreed to help and urged Alexandra to accompany Aristobulus to meet Antony. Herod, fearing that Aristobulus would be crowned king, had him assassinated.

Herod was said to have been an utterly despotic and tyrannical ruler who ruthlessly suppressed any murmurs against him. Any opponents, including family members, were immediately removed from the equation. Historians suggest that he may have had a secret police of sorts to keep abreast of and control the opinions of the common people about him. Suggestions of revolt or even protests against his rule were dealt with forcefully. According to Josephus, he had a tremendously large personal guard of 2000 soldiers.

Herod is known for the great architecture of Judea, and the temples that he built. But this too is not without its own negative connotations since these great expansions and building projects required a lot of funding. To this end, he heavily taxed the Judean people. Although the building projects provided employment opportunities to many, and Herod is said to have taken care of his people in times of crisis, such as the famine of 25 BCE, the heavy taxation did not endear him to his people.

King Herod was a lavish spender and emptied the royal coffers to fund expensive and unnecessary gifts to create a reputation of generosity and great wealth. This was looked upon with disapproval by his subjects.

The Pharisees and the Sadducees, the most important sects among the Jews at the time, were both firmly opposed to Herod. They asserted that he did not heed their demands regarding the construction and appointments at the Temple. Herod tried to reach out to the greater Jewish diaspora, but he was largely unsuccessful in this, and resentment against the king reached a boiling point in the later years of his rule.

Relationship With the Roman Empire

When the struggle for the position of the Roman ruler started between Mark Antony and Octavian (or Augustus Caesar as he is better known) due to the marriage of Antony and Cleopatra, Herod had to decide which of them he would support. He stood by Antony, who had been his patron in many ways and to whom Herod owed Herod’s kingdom.

Herod ruled Judea under the aegis of the Romans, even if his titles, like Herod the Great and King of the Jews, may have indicated that he was an independent ruler. His support of the empire and the fact that he was recognized as an allied king is what enabled him to rule Judea. While he did have some level of autonomy within his kingdom, there were restrictions placed on him regarding his policies towards other kingdoms. After all, the Romans could not afford to have their vassal states build alliances out of their purview.

King Herod’s relationship with Augustus seems to have been delicate since he first rejected his right to rule imperial Rome. Perhaps this was why he had to work doubly hard to keep the Romans happy in the later years of his reign. Roman rule was not just about conquering territories but also spreading Roman culture, art, and way of life to those territories. King Herod had to balance keeping his Jewish citizens happy and the spread of Roman art and architecture in Rome as per the whims of Augustus.

Thus, we see a great deal of Roman influence in the temples and monuments that Herod built during his reign. In fact, the third temple that he constructed to honor Augustus was called the Augusteum. What his private views on the emperor were isn’t known, but it is clear Herod knew very well who he needed to keep happy.

Herod the Builder

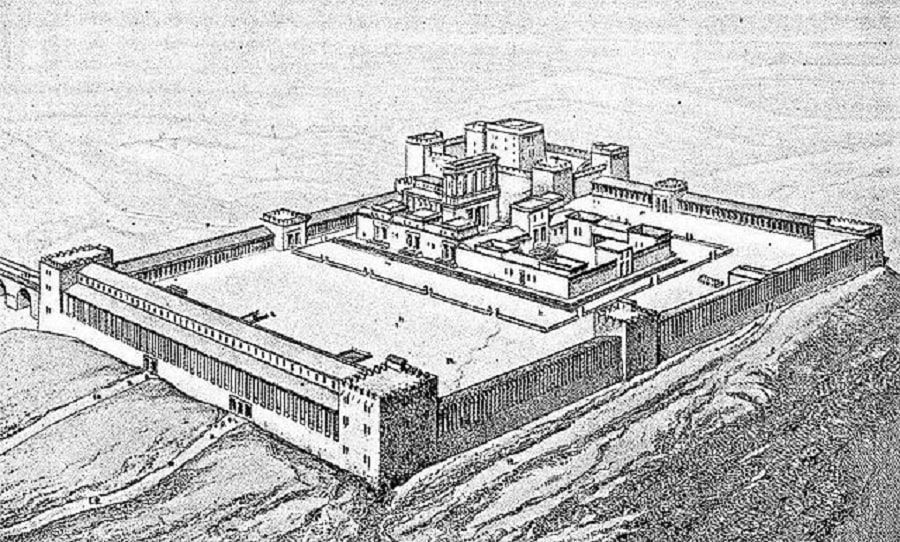

One of the few positive things King Herod was known for was his building talent and the way architecture flourished during his reign. While this was not an unmixed positive note, he has left behind a legacy of architectural achievements. This not only included the great Second Temple but also fortresses, aqueducts to provide water to the people, new cities, and perhaps ships. Almost all of the architecture is in the classical Roman style, an indication of Herod’s eagerness to hold on to Roman support.

The project that Herod is best known for is the expansion of the Second Temple of Jerusalem. This temple replaced Solomon’s Temple, built on the same site where it had been located. The Second Temple had already existed centuries before Herod took the throne, but King Herod wished to make it even greater and more magnificent. It was partly due to his wish to win over his Jewish citizens and earn their loyalty. It was probably in part also the enduring legacy he wished to leave behind to make himself Herod the Great, King of the Jews.

Herod rebuilt the Temple in around 20 BCE. Work continued on the temple for many years, far beyond Herod’s death, but the main temple was completed in a very short time. Since Jewish law required priests to be involved in the construction of temples, Herod is said to have employed 1000 priests for masonry and carpentry work. This completed temple came to be known as Herod’s Temple, although it did not stand very long. In 70 CE, the Second Temple, the center of Jewish worship in Jerusalem, was destroyed by the Romans during the Roman Siege of Jerusalem. Only the four walls that made up the platform on which the temple stood still remain.

Herod also built the port city of Caesarea Maritima in 23 BCE. This impressive project was meant to consolidate his power as a major economic and political force in the Mediterranean. Herod, apart from Queen Cleopatra, was said to be the sole ruler allowed to extract asphalt from the Dead Sea, which was used to build ships. Herod also undertook projects to supply water to Jerusalem and import grain from Egypt to deal with natural disasters such as drought, famine, and epidemics.

Other construction projects undertaken by King Herod were the fortresses of Masada and Herodium, as well as a palace for himself in Jerusalem named Antonia. Interestingly enough, Herod is also said to have provided funds for the Olympic Games around 14 BCE since the Games were suffering from dire economic straits.

Death and Succession

The year of Herod’s death is uncertain, although the nature of it seems clear. Herod died of a long and reportedly painful illness that has not been identified. According to Josephus, Herod was so maddened by the pain that he attempted to take his own life, an attempt that was foiled by his cousin. Later accounts, however, report that the attempt succeeded.

According to various sources, Herod’s death may have occurred between 5 BCE and 1 CE. Modern historians believe it was most probably in 4 BCE because the reign of his sons Archelaus and Philip begins in that year. The account in the Bible complicated matters since it states that Herod died after the birth of Jesus Christ.

Some scholars have challenged the idea that Herod died in 4 BCE, stating that his sons might have backdated the start of his reign to a time when they began consolidating more power.

King Herod was apparently so paranoid about not being mourned after his death that he ordered the deaths of several distinguished men immediately after his death so there would be vast mourning. It was an order that his chosen heir Archelaus and his sister Salome did not carry out. His tomb was located in Herodium, and in 2007 CE, a team led by archaeologist Ehud Netzer claimed to have found it. However, no remains of a body were discovered.

Herod left behind several sons, which led to quite a succession crisis. His chosen heir was Herod Archelaus, the eldest son of his fourth wife Malthace. Augustus recognized him as Ethnarch, although he was never formally called king and was soon removed from power for incompetency anyway. Herod had also willed territories to two of his other sons. Herod’s son, Herod Antipas, was the Tetrarch of Galilee and Peraea. Herod Philip, son of Herod’s third wife Cleopatra of Jerusalem, was the Tetrarch of certain territories towards the north and east of Jordan.

The Many Wives of King Herod

King Herod had several wives, whether at the same time or one after another, and many sons and daughters. Some of his sons were named after him, while some have become known for being executed because of Herod’s paranoia. Herod’s tendency to kill his own sons was one of the major reasons why he wasn’t loved by his people.

Herod put aside his first wife Doris and their son Antipater, sending them away so that he could marry the Hasmonean princess Mariamne. And yet, this marriage too was doomed to failure as he grew suspicious of her royal blood and perceived ambitions for the throne. Since Mariamne’s mother, Alexandra was scheming to put her son on the throne, perhaps his suspicions were not unfounded.

Disturbed by her husband’s suspicions and schemes, Mariamne stopped sleeping with him. Herod accused her of adultery and put her on trial, a trial that Alexandra and Herod’s sister Salome I stood witness. Then he had Mariamne executed, followed shortly by her mother. The following year, he also executed Salome’s husband Kostobar for conspiracy.

Herod’s third wife was also named Mariamne (her official title was Mariamne II), and she was the daughter of the High Priest Simon. His fourth wife was a Samaritan woman named Malthace. Other wives of Herod were Cleopatra of Jerusalem, mother of Philip, Pallas, Phaidra, and Elpis. He was also said to have been married to two of his cousins, although their names aren’t known.

Children

Since Herod’s father had died by poisoning, probably at the hand of a family member or one of his close circle, Herod carried that paranoia into his kingship. Having replaced the Hasmoneans, he was deeply suspicious of plots to overthrow him and replace him in turn. Thus, his suspicion towards the wife and sons who were Hasmonean by birth was doubly dreadful. In addition to Mariamne’s execution, Herod suspected his three eldest sons of conspiring against him several times and had them all executed.

After the death of Mariamne, his banished eldest son Antipater was named heir in his will and brought back to court. By this time, Herod had begun to suspect that Mariamne’s sons Alexander and Aristobulus wished to assassinate him. They were reconciled through the efforts of Augustus once, but by 8 BCE, Herod had accused them of high treason, brought them to trial before a Roman court, and executed them. In 5 BCE, Antipater was brought to trial on suspicions of the intended murder of his father. Augustus, as the Roman ruler, had to approve the death penalty, which he did in 4 BCE. Antipater followed his half-brothers to the grave.

Subsequently, Herod named Herod Archelaus his successor, with Herod Antipas and Philip being given lands to rule over as well. After Herod died, these three sons received lands to rule over, but since Augustus had never approved Herod’s will, none of them ever became King of Judea.

Mariamne II and Herod’s granddaughter, through their son Herod II, was the famous Salome, who received the head of St John the Baptist and was the subject of much Renaissance-era art and sculpture.

King Herod in the Bible

Herod is rather notorious in the modern consciousness for the incident called the Massacre of the Innocents by the Christian Bible, even though historians now claim that this incident did not actually take place. Indeed, historians familiar with Herod and his writing as his contemporaries, like Nicolaus of Damascus, make no mention of such a crime.

Herod and Jesus Christ

The Massacre of the Innocents is mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew. The story goes that the magi or a group of wise men from the East visited Herod because they had heard a prophecy. The magi wanted to pay their respects to the one who had been born king of the Jews. Herod, very alarmed and aware that this was his title, immediately began to make inquiries about who this prophesied king might be. He learned from scholars and priests alike that the child would be born in Bethlehem.

Herod sent the magi to Bethlehem accordingly and asked them to report back to him so that he could pay his respects too. The magi warned Joseph, the father of Jesus in a dream, to flee Bethlehem with his pregnant wife, and he took her to Egypt.

Herod had all boys under the age of two in Bethlehem killed to get rid of the threat. But baby Jesus’ family had already fled and stayed away from the reach of both Herod and his son Aechaulus in the years that followed, moving eventually to Nazareth in Galilee.

Most modern historians and writers agree that this story is more myth than fact and that it did not happen. It was meant as a sketch of Herod’s character and reputation more than anything. Perhaps it was meant to be parallel to Herod’s murder of his own sons. Perhaps it was a byproduct of the cruelty and ruthlessness of the man. At any rate, there is little reason to interpret the biblical story literally or to think that Herod was aware of the birth of Jesus Christ.

While there is no evidence that the Massacre of the Innocents did take place, a tragic event in around 4 BCE may have been the source of the fable. Several young Jewish boys destroyed the golden eagle, the symbol of Roman rule placed above the gateway of Herod’s Temple. In retaliation, King Herod had 40 students and two teachers killed brutally. They were burned alive. While not exact, the timing of the Biblical story is very similar and could have arisen from this cruel act.