Julius Caesar and Cleopatra played significant roles in ancient history, and their relationship, while short-lived, had a significant impact on both their lives and the course of history. While they even allegedly produced a child together, theirs was a relationship forged primarily in their mutual need to grab and hold power in their individual domains.

Their alliance solidified the unpopular queen’s position in Egypt, allowing her to claim her place in history as the last true Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. Her wealth, meanwhile, gave Caesar the resources he needed to hold on to power in Rome after his term as consul expired in 48 B.C.E.

Table of Contents

Who Were Julius Caesar and Cleopatra?

Julius Caesar was an ambitious and fearless ruler who heralded the end of the Roman Republic and became known (posthumously) as the first Roman Emperor. Cleopatra was the last in a line of Greek rulers holding tenuous control over ancient Egypt.

In their time, these two figures – both separately and through their partnership – made giant marks on their respective nations. But who were they, and what in their individual stories set them on the path to their alliance?

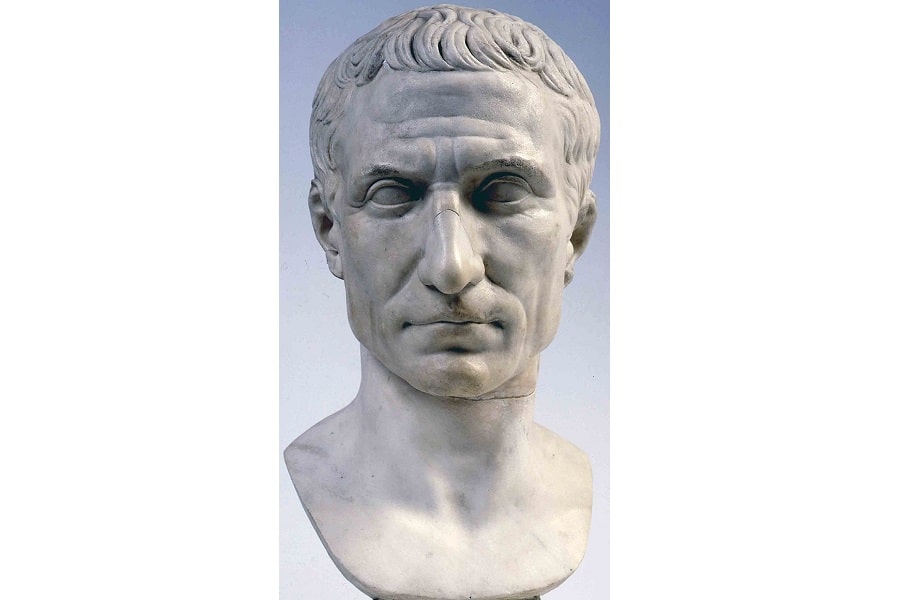

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on July 12th of 100 B.C.E. in the sprawling Suburra neighborhood of Rome. His father had been a praetor, or elected magistrate, of a wealthy province of modern-day Turkey, while his mother came from the influential Aurelia family which had produced a number of political leaders.

Though his was a patrician family, that meant relatively little by the 1st Century B.C.E. – many of the old patrician families had gone extinct, and their political power was much diminished as compared to that of the plebs. Indeed, as it barred him from the immensely powerful office of tribune of the plebs, Caesar’s patrician heritage actually hindered his own political ambitions.

Exile and Rise

Just as Julius Caesar became head of his family (at the age of 16), Rome found itself in a civil war. The Roman general Sulla seized control of the Republic – the first to do so by force – and mercilessly began divesting and executing his enemies – a process known as “proscription.”

READ MORE: Roman Wars

Having married into the family of Sulla’s chief rivals, Julius Caesar was on that enemies list. Fortunately, his own family had many strong Sulla supporters, who intervened on his behalf and earned Julius Caesar a pardon and exile, which the young Roman spent in Asia Minor in the Roman Army.

He would return to Rome in 79 B.C.E. when Sulla died and began his political career by establishing himself as a prosecuting advocate. In the years that followed, he would rise through a number of offices and – after a stint as governor of Hispania Ulterior (the southern areas of modern-day Spain and Portugal) – Julius Caesar at last attained Rome’s highest elected office, consul, in 59 B.C.E.

Following his consulship, Julius Caesar took another post as governor – this time in the province of Gallia Narbonensis, in southern France. Here – on his own initiative – he spent the next eight years using the legions at his disposal to conquer Gaul, accumulating substantial wealth in the process.

In 52 B.C.E., Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, aka Pompey the Great, took advantage of rampant political violence to secure an unprecedented sole consulship. During his tenure, he made a number of moves seemingly calculated to disadvantage the popular Julius Caesar and perhaps open him to prosecution.

The animosity between the two came to a head when Julius Caesar brought a legion to the very borders of the Roman Republic, threatening to invade Rome if Pompey did not agree to a compromise that disarmed both forces. Pompey refused, and in January of 49 B.C.E., Julius Caesar crossed the shallow river called the Rubicon – the official border across which no army was to be brought – and set off the Roman civil war against Pompey in earnest and putting him on the path to his alliance with Cleopatra.

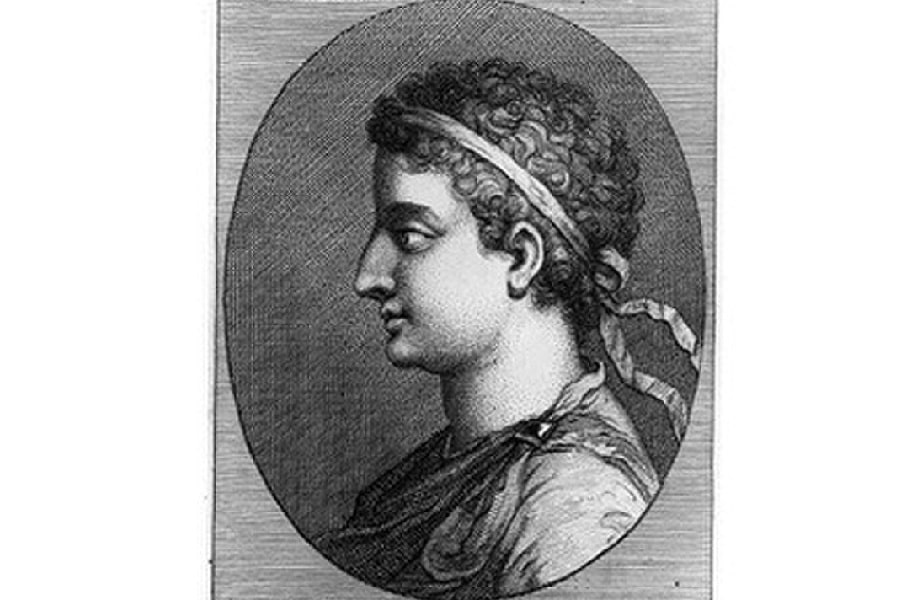

Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII, also called Cleopatra Theo Philopater (“father-loving goddess”), was born around 70 B.C.E., the daughter of Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy XII. She was part of the Ptolemaic line of rulers, descended from Ptolemy I, the Macedonian general who’d served under Alexander the Great and founded the dynasty about 304 B.C.E.

READ MORE: The Queens of Egypt: Ancient Egyptian Queens in Order

She was the first Ptolemaic pharaoh to actually learn the Egyptian language (the Ptolemies, as a Macedonian line, spoke Koine Greek), and may have spoken as many as nine languages. A highly educated woman, she had studied math, philosophy, astronomy, and oratory.

While she is popularly remembered for her seductive beauty, that aspect of the queen is likely exaggerated. Rather, her power over men was more based on a shrewd charm and political savvy.

A previous pharaoh, Ptolemy X – the uncle of Cleopatra’s father – had written in his will that Egypt should go to Rome if the Ptolemaic line ever failed to produce an heir. This, coupled with the rising power of the Roman Republic, made Rome’s annexation of Egypt an increasingly likely threat (it had been openly suggested in the Senate as early as 65 B.C.E.).

Indeed, Rome annexed nearby Cyprus in 58 B.C.E., deposing the pharaoh’s brother who had ruled as king. So, when a rebellion in his country deposed him around 59 B.C.E. and installed his older daughter, Berenice, Ptolemy XII had little choice but to strike a deal with Rome (where, at the time, Julius Caesar was serving as consul) for military support to retake his throne – and for recognition of his right to rule, so he could keep it.

Cleopatra the Pharaoh

Ptolemy VII ascended the throne again, this time naming Cleopatra as his co-regent, with Egypt continuing as a client state under their rule but still answerable to the growing power of the Roman Republic. This is the Egypt that Cleopatra would inherit when her father died in 51 B.C.E.

Ptolemy XII’s will stated that Cleopatra and her 11-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII, would marry and reign as co-rulers (sibling marriage was a longstanding tradition of Egyptian rulers which the Ptolemies continued). The more dominant Cleopatra swiftly took charge, and Egyptian documents soon began listing her as the sole ruler, ignoring the younger Ptolemy.

But her sibling, though young, still had influential supporters. With the help of a cabal of his advisors, chiefly the eunuch Potheinos, Ptolemy XIII reasserted himself and by 50 B.C.E. clearly had the upper hand, and Cleopatra and her supporters were forced to flee Alexandria for Thebes around the same time Julius Caesar was crossing the Rubicon.

She raised an army with help from Roman Syria but was unable to advance all the way to Alexandria. Stymied by her brother’s forces, she camped near the city Pelusium, near modern-day Port Said, where she would remain until Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt.

READ MORE: The Lighthouse of Alexandria: One of the Seven Wonders

Caesar and Cleopatra

In August of 48 B.C.E., Julius Caesar crushed the army of Pompey and his allies near Pharsalus (now Farsala) in southern Greece despite being outnumbered nearly two to one. Desperate, Pompey fled to what he believed was his only remaining ally – Ptolemy XIII, who for the moment had wrested the throne from his sister.

Pompey had been close with Ptolemy’s father, and the elder Ptolemy had fought beside Pompey in the past. He had expected to regroup and continue his war against Julius Caesar from the shelter of Ptolemy XIII’s Egypt.

But his assumed ally had other ideas. Ptolemy’s advisors had convinced him to be wary of allowing Pompey to turn Egypt into a base for his war against Julius Caesar – not to mention, the young ruler had no desire to draw the wrath of the victorious dictator.

When Pompey sought refuge in Egypt, Ptolemy feigned welcome. But no sooner had the Roman leader arrived in Alexandria than he was fallen upon by assassins acting on Ptolemy’s orders.

Just three days later, Julius Caesar arrived in pursuit. Ptolemy presented him with Pompey’s head, hoping the gesture would win Julius Caesar’s favor. In fact, it disgusted the dictator – foe or not, Pompey had been a fellow Roman who deserved a Roman funeral, not such a barbaric fate at the hands of the Egyptians.

His term as dictator was extended in absentia. Unable to leave immediately due to the strong seasonal winds in the Mediterranean, Julius Caesar installed himself in the country and decided to arbitrate the civil war between Ptolemy and his sister – assuming, in his typical fashion, the authority to do so.

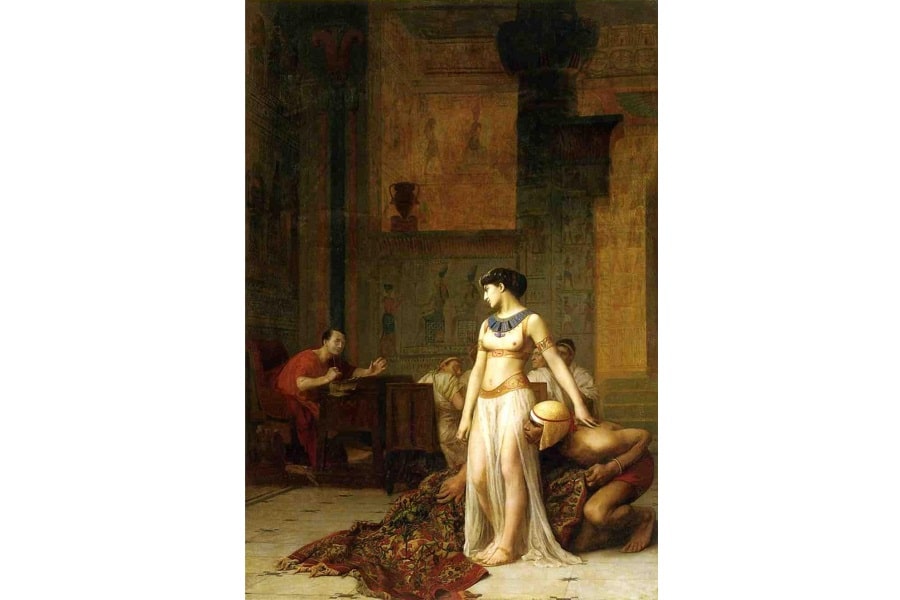

Meeting of the Minds

To judge the conflict, Julius Caesar needed to speak to both contenders. But with Alexandria firmly in Ptolemy’s hands, Cleopatra didn’t dare try to enter the city, even with Julius Caesar’s legion in place.

So, the queen was smuggled into the city. Disguising her servant as a merchant, Cleopatra rolled herself up in a carpet. The “merchant” then rowed into the city, delivered the carpet to the dictator’s private room, and unrolled it to reveal the queen.

The cleverness of the ploy impressed the Roman leader immediately. And by the end of that first meeting, her wit and charm had put Julius Caesar firmly into Cleopatra’s camp and set the stage for both their partnership and their romance.

Mutual Needs

Cleopatra clearly needed help to wrest control from her brother and retake her place as queen of Egypt. And she recognized this arbitration – and, if need be, Julius Caesar’s military prowess – as the best available tools to that end.

And while Julius Caesar was taken with the young queen’s charisma and intellect, her wealth was equally appealing. The death of Pompey was only one more step in his own quest for power. He still had enemies to defeat, provinces to subdue, and various political machinations to enact once he returned to Rome in order to secure his own power.

All of that would require money and no small sum of it. And the charming young queen that needed his help to take back her throne was, at the time, the richest woman in the world. So it was that the two most powerful people in the region came together at just the right time to help each other reach their goals.

Judgment and the Siege of Alexandria

In the aftermath of his meeting with Cleopatra, Julius Caesar made a ruling that she and Ptolemy should return to their original status as co-rulers. Potheinos – the same advisor that had played an instrumental part in turning Ptolemy against his sister in the first place – protested that the terms of this restored arrangement leaned too heavily in favor of Cleopatra.

Other Ptolemy supporters agreed, and in short order, the forces of the young king had laid siege to the palace. Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, along with approximately 4000 Roman troops, were trapped inside the palace complex for some four months, until January of 47 B.C.E.

That was when reinforcements finally came – approximately 13,000 Roman-trained troops from Asia Minor under the command of Julius Caesar’s ally Mithridates of Pergamum. Mithridates entered Egypt, took Pelusium then continued through the Nile Delta.

Once word reached Alexandria that Mithridates’ army was on the way, Ptolemy redeployed a portion of his forces in an unsuccessful attempt to stop them at the Nile Delta. With this army defeated Ptolemy had no choice but to lift the siege and head eastward to meet Mithridates himself. Leaving a garrison in control of Alexandria, Julius Caesar likewise led his forces out to meet up with the reinforcements for a battle that would decide Egypt’s civil war.

The Battle of the Nile

While Ptolemy headed overland with his forces, Caesar took his by sea, reaching Mithridates’ army at their fortified camp on the eastern bank of the Nile before Ptolemy’s combined forces could stage an attack. Ptolemy joined with the remnants of his earlier force on the western side of the Nile, who’d been brutally routed when they’d previously attempted to cross the Nile and attack the much more organized force of Roman allies.

Now, Julius Caesar’s and Mithridates’ combined forces numbered some 20,000 men, all trained and equipped in Roman military style. Across the river, they faced a slightly larger force of Greek-equipped Egyptians.

Ptolemy set a detachment to prevent the Romans from fording the river, though he dispatched them too late. Julius Caesar had already sent his Germanic cavalry across the river undetected, even as his main force began constructing simple log bridges to cross the Nile.

Once ready, the Roman forces began their crossing – and the Alexandrian invaders suddenly found themselves attacked from the flanks by Julius Caesar’s advance cavalry. As before, the Alexandrian forces were routed.

Many of the broken army attempted to flee in boats, including Ptolemy himself. But his overloaded ship capsized, and the young ruler was killed, finally ending the Egyptian civil war.

After the Battle

In the aftermath of the war, Julius Caesar again announced Cleopatra as co-ruler of Egypt – this time with another brother, Ptolemy XIV, who was only twelve years old at the time. With his ally now firmly ensconced in power, Caesar’s work in Egypt was done – but he didn’t leave just yet.

Despite his own continuing civil war, Julius Caesar would stay in Egypt for another two months, not leaving the country until April. He and the queen carried on their affair in earnest during this time – even supposedly taking a cruise on the Nile together – and it would result in Julius Caesar’s only known biological son – Ptolemy XV, nicknamed Caesarion, or “little Caesar,” born that June.

Julius Caesar would never officially acknowledge the paternity of the child – perhaps because he was married at the time to a noblewoman named Calpurnia – and some allies in Rome even authored pamphlets attempting to prove the boy could not be his. It must be noted, though, that he also never publicly disputed paternity or objected to the boy’s nickname.

Cleopatra in Rome

After leaving Egypt, Julius Caesar hurried to Zela in modern-day Turkey to battle the army of Pharnaces II, ruler of the Bosporan Kingdom of modern-day Crimea, who had taken the opportunity of the Roman civil war to try and retake the Roman province of Pontus on the Black Sea. Julius Caesar swiftly defeated Pharnaces, marking the occasion with one of his most famous quotes – “veni, vidi, vici,” or “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

He then returned to Italy to peacefully quell the riots that had risen against the unpopular magister equitum he’d left to run things in his absence, Mark Antony. His stay was brief, however, as he had to set out for Africa to vanquish the forces of Metellus Scipio, Pompey’s father-in-law, and Cato the Younger, a longtime critic in the Senate, who had set themselves in Utica, in modern-day Tunisia.

With these enemies defeated Julius Caesar returned to Rome once more in June of 46 B.C.E. Later that year, he was joined by Cleopatra, who came to Rome as a visiting client queen and was giving accommodations at Julius Caesar’s villa.

She would remain in Rome for two years, though it is uncertain if her son Caesarion joined her. While there, she met with members of the Senate and other dignitaries, and the Greek astronomer Sosigenes (a member of her court) aided Julius Caesar in his creation of the Julian calendar. A golden statue of the queen was even cast and placed in the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar.

Little else is known of her time in Rome. It is possible, even likely, that her affair with Julius Caesar continued, though – as Julius Caesar was still married and conscious of his public opinion for political reasons – it was almost certainly much more discreet.

Endings

Julius Caesar departed Rome again in 45 B.C.E., this time heading to Spain where two of Pompey’s sons and Caesar’s former lieutenant, Titus Labienus, had seized control. In a pitched battle near present-day Montilla that June, Julius Caesar narrowly defeated these last enemies, leaving no remaining opposition to his rule.

Unlike Sulla, Julius Caesar pardoned most of his enemies and faced no real direct opposition in public sentiment. He celebrated triumphs upon his return for defeating “foreign” enemies – though the fact that many of these enemies had actually been Roman opponents on foreign soil left a bad odor on the whole affair for many Romans.

At the Lupercalia festival of 44 B.C.E. (held in mid-February), Mark Antony had made a public show of attempting to place a crown on Julius Caesar’s head, with the dictator refusing – an almost certainly staged performance to assess public sentiment on the institution of a monarchy. It was, in any case, an empty gesture – Julius Caesar had previously given himself a number of unique and far-reaching powers, had worked to centralize power in Rome to an unprecedented degree, and around the same time as the festival had been named dictator in perpetuity, making him a king in all but name.

Just a month later, on March 15th, Julius Caesar came to appear at a session of the Senate when he was ambushed and attacked by a conspiracy of several Senators. The dictator would be stabbed some 23 times, and – after a lifetime of military and political conquest – died on the floor of the Senate just as he had achieved his loftiest goal.

READ MORE: How Did Julius Caesar Die? Betrayed and Stabbed to Death

But while they saw themselves as liberators, the assassins were coldly received by the public. And while they avoided punishment for their actions, they failed to reinstate the Republic – instead plunging Rome into a new series of civil wars that would ultimately see Julius Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian, officially founding the Roman Empire.

The End of the Ptolemies

Cleopatra remained in Rome just long enough to be convinced there was no chance of Caesarion being named Julius Caesar’s successor. By April, she had set out for Egypt again.

Shortly after her return, she poisoned her brother and co-regent, Ptolemy XIV. Her son now ascended to be her co-ruler, as Ptolemy XV.

Julius Caesar’s ally, Mark Antony, had entered into a short-lived Second Triumvirate with Octavian and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to try and stabilize the Republic. But just over a year later it had degenerated into a division of Roman territory between Mark Antony, who controlled the eastern half, and Octavian, who held the western half.

Cleopatra forged a romantic/political alliance with Antony as she previously had with Julius Caesar. Their relationship, though originating in the same sort of mutual need as her fling with Julius Caesar, would be remembered much more as a love story, immortalized first by the Greek historian Plutarch and later by the playwright William Shakespeare.

The two would produce three children together – Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. And their relationship would go on for a decade, ending only when Octavian invaded Egypt and defeated Antony’s forces once and for all.

In the wake of the defeat, Antony – spurred on by a message from Cleopatra claiming her own intention to commit suicide, drew his sword and took his own life. Refusing to give Octavian the victory of capturing her and parading her in a tribute, Cleopatra did ultimately commit suicide, on August 10th, 30 B.C.E. – according to legend, either by allowing a cobra to bite her or otherwise poisoning herself with its venom.

READ MORE: How Did Cleopatra Die? Bitten by an Egyptian Cobra

Caesarion, aka Ptolemy XIV, became the sole pharaoh of Egypt upon his mother’s death, but his reign lasted only 18 days. Lured back to Alexandria by Octavian’s promise that he would be allowed to rule Egypt, the boy was instead executed on the Roman leader’s orders – bringing an end to both the Ptolemaic dynasty and the story of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra.