Nestled between the rolling hills and vibrant green landscapes of modern-day Scotland lies the whisper of an ancient boundary, the Antonine Wall. This relic of Roman ambition once stretched boldly across the narrow neck of land between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde, a testament to the reach and power of one of history’s greatest empires.

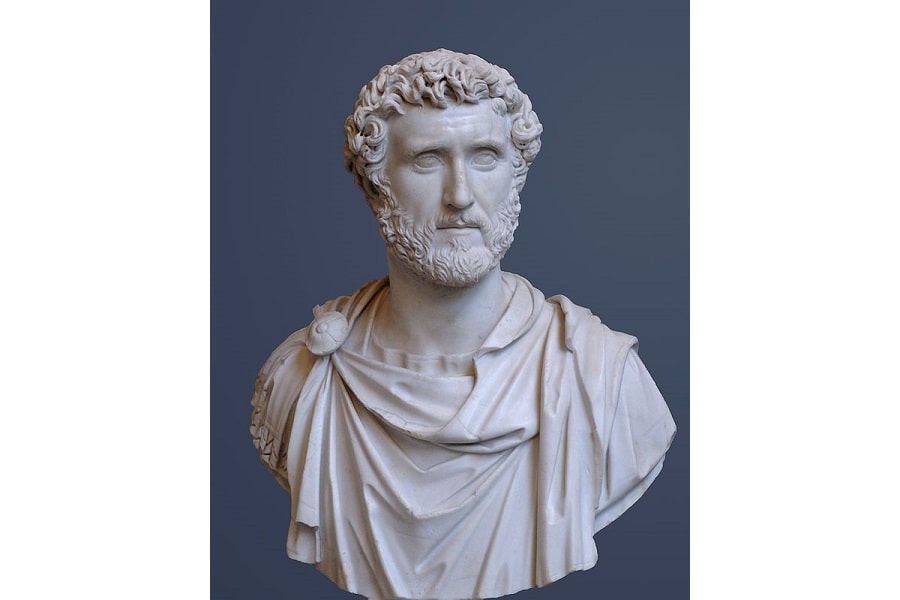

Constructed under the orders of Emperor Antoninus Pius in the second century AD, the wall was more than a mere barrier; it was a statement of control, a marker of the Roman Empire’s northern frontier in Britain.

Unlike its more famous counterpart to the south, Hadrian’s Wall, the Antonine Wall was built not of stone, but of turf and timber, and its remains tell a story of military strategy, ancient engineering, and a fleeting moment of expansionism that has captivated historians and archaeologists alike.

Through the echoes of its past, the Antonine Wall offers a unique lens into the complexities of Roman Britain, inviting us to uncover the reasons behind its construction, the lives it touched, and the reasons for its eventual abandonment.

Table of Contents

Who Built the Antonine Wall and Why?

In the mid-second century AD, the Roman Empire, under the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, embarked on a significant yet relatively lesser-known military and architectural venture in the far reaches of its northern territory in Britain.

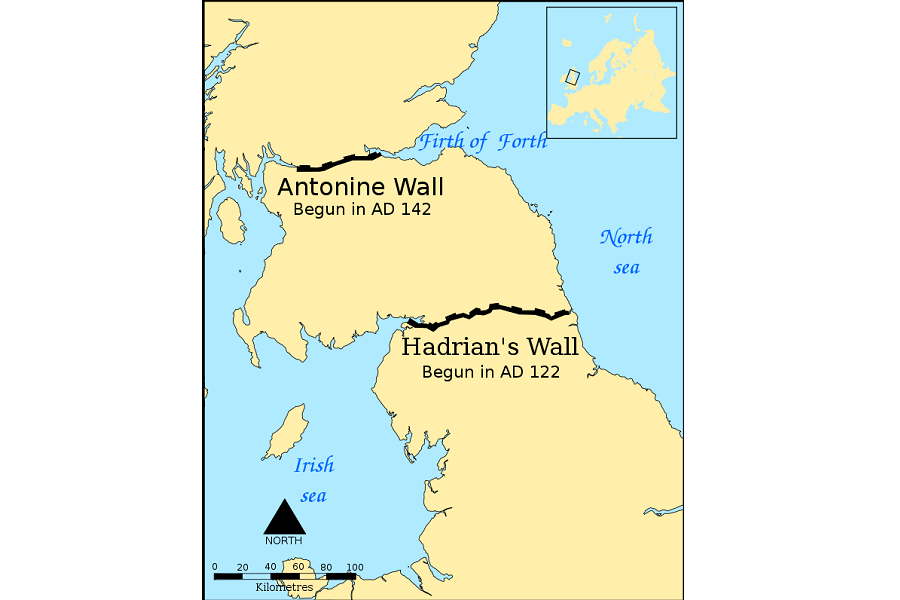

The Antonine Wall, named after the emperor himself, was constructed as a frontier fortification, stretching approximately 60 kilometers (about 37 miles) across what is now Scotland.

This monumental task was undertaken around AD 142, shortly after Antoninus Pius ascended to the throne, signaling a shift in Roman military strategy and a renewed ambition to exert control over the northern tribes of Britain.

The construction of the Antonine Wall was primarily a military decision, aimed at advancing the Roman frontier northward from Hadrian’s Wall, which had been established a couple of decades earlier.

The motivations behind this ambitious project were multifaceted.

Politically, it was a means for Antoninus Pius to leave his mark on the empire, demonstrating his power and capability as a leader.

Militarily, the wall served as a deterrent against the Caledonian tribes, who posed a constant threat to the Roman-controlled territories in Britain.

By moving the frontier north, the Romans hoped to secure more favorable strategic positions and facilitate easier access to the rich natural resources of the region.

The construction of the wall was an engineering marvel of its time. Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, which was primarily built of stone, the Antonine Wall was constructed using turf and wood, materials that were readily available in the surrounding landscape.

This decision was likely influenced by the need for speed in construction and the logistics of transporting building materials across the rugged terrain of northern Britain.

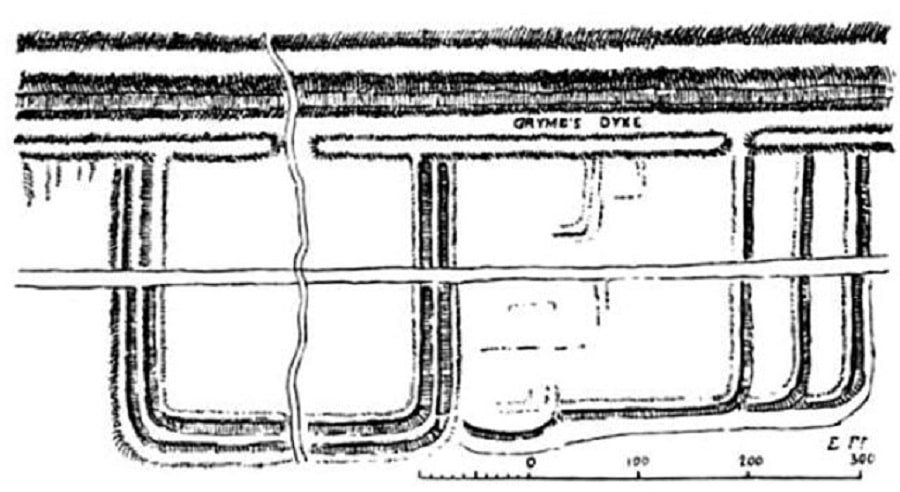

The wall itself was accompanied by a deep ditch on the northern side and a military road known as the “Military Way” on the southern side, enhancing its defensive capabilities and facilitating troop movements.

The decision to build the Antonine Wall, therefore, was a strategic one, reflecting the Roman Empire’s broader objectives of security, control, and expansion. It was a statement of intent, a physical manifestation of Rome‘s desire to dominate and civilize the northern reaches of Britain.

Yet, as history would show, this ambition would be short-lived, with the wall serving its purpose for only a couple of decades before the Romans retreated back to Hadrian’s Wall.

Architecture Behind the Antonine Wall

The architecture of the Antonine Wall showcases a blend of Roman military engineering prowess and adaptability to the challenging landscapes of northern Britain. Constructed primarily from layers of turf laid on a stone foundation, the wall exemplified Roman innovation in frontier fortification design.

The choice of turf, a departure from the predominantly stone constructions found elsewhere in the empire, was a pragmatic response to the local environment and the urgency of establishing a northern boundary.

The stone foundation provided a durable base, ensuring stability and longevity for the turf structure above, a method that leveraged local resources effectively while adhering to Roman architectural principles.

Rising to a height of about 3 meters (nearly 10 feet) and up to 5 meters (16 feet) wide at its base, the wall was a formidable barrier, further reinforced by a wide and deep ditch on the northern side, known as the “vallum.”

This ditch, typically around 12 meters (39 feet) wide and 3.6 meters (12 feet) deep, was designed to impede any potential attackers, adding an extra layer of defense to the sophisticated frontier system.

The presence of the ditch not only demonstrated the Romans’ strategic defensive planning but also their understanding of landscape manipulation for military purposes.

Strategically placed along the wall were approximately 20 forts, with additional fortlets and watchtowers positioned at regular intervals, providing housing for the garrison troops and enabling surveillance over the surrounding areas.

These structures were integral to the operation and effectiveness of the Antonine Wall as a military frontier. The forts varied in size and construction but generally included barracks, command centers, granaries, and bathhouses, embodying the Romans’ ability to create self-sustaining military outposts.

The “Military Way,” a road that ran parallel to the wall on the southern side, was another critical architectural feature, facilitating rapid troop movements and communication between forts. This road underscored the logistical ingenuity of the Romans, ensuring that reinforcements and supplies could be quickly dispatched along the wall’s length.

READ MORE: The Roman Army

Why Did the Romans Abandon the Antonine Wall?

The abandonment of the Antonine Wall, roughly two decades after its construction, reflects the dynamic and challenging nature of Rome’s northern frontier in Britain. Several factors, both military and economic, contributed to the Roman decision to retreat to the more defensible Hadrian’s Wall to the south.

One of the primary reasons for the abandonment was the persistent resistance from the local Caledonian tribes. Despite the wall’s strategic advantages and the presence of a formidable Roman military force, the Caledonians’ guerrilla tactics and deep knowledge of the local terrain posed constant threats to Roman control.

The cost of maintaining such a vast and exposed frontier, both in terms of resources and manpower, became increasingly unsustainable, especially in the face of determined resistance from local tribes.

Economic considerations also played a crucial role in the decision to abandon the Antonine Wall. The logistical challenges of supplying and reinforcing this remote frontier demanded significant resources.

The Roman Empire, during the latter part of the 2nd century AD, faced pressures on multiple fronts, including military campaigns in other parts of the empire and internal political instability.

These factors strained the empire’s finances and resources, compelling a strategic reassessment of priorities. The maintenance of the Antonine Wall, under these circumstances, was deemed less critical than securing other, more vulnerable parts of the empire.

Furthermore, changes in Roman military strategy and imperial policy under subsequent emperors influenced the decision to abandon the Antonine Wall. The shift towards a more defensive posture, focusing on consolidation rather than expansion, made the occupation of the Antonine Wall less appealing.

Hadrian’s Wall, with its more durable stone construction and shorter length, offered a more manageable and economically sustainable option for controlling the northern frontier of Roman Britain.

Environmental factors may have also contributed to the abandonment. The harsh Scottish climate and the challenges it posed to the maintenance of the turf and timber construction of the Antonine Wall could have further undermined its viability as a long-term defensive structure.

Is There Anything Left of the Antonine Wall?

Today, the Antonine Wall stands as a shadow of its former self, yet significant remnants and archaeological finds along its route offer a tangible connection to its historical past. Although the wall’s original turf and timber structure has largely eroded over the centuries, the footprint of Roman ambition is still visible across the Scottish landscape.

The preservation and excavation of these remains have provided invaluable insights into Roman engineering, military strategy, and daily life on the empire’s northern frontier.

Visible traces of the Antonine Wall include the earthworks of the vallum, or defensive ditch, which in some places remains a pronounced feature in the terrain. These earthworks, though weathered by time, continue to mark the boundary the wall once delineated.

In addition to the ditch, the foundations of several forts and fortlets that punctuated the wall at regular intervals have been uncovered. These archaeological sites reveal the layout and structure of Roman military installations, including barracks, granaries, and command centers.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Antonine Wall’s legacy is the discovery of distance slabs. These elaborately carved stone monuments were erected by the Roman legions who constructed the wall, commemorating their achievements and dedicating their work to the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius.

READ MORE: Roman Emperors in Order: The Complete List from Caesar to the Fall of Rome and Roman Legion Equipment

The slabs, many of which are now housed in museums, are adorned with intricate reliefs depicting Roman army military victories and symbols of imperial power, offering a unique glimpse into the propaganda and artistic expression of the time.

READ MORE: Roman Army Tactics

Moreover, the Antonine Wall’s route is now a significant historical and cultural landmark, recognized for its historical importance. Efforts have been made to conserve its remnants and to make them accessible to the public.

Several sections of the wall and its associated sites are now part of a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site, highlighting their global significance and ensuring their preservation for future generations.

In addition to physical remains, the Antonine Wall has left a rich archaeological record, including artifacts such as Roman coins, pottery, weapons, and personal items that provide insights into the lives of those who lived and served along the wall.

READ MORE: Roman Weapons: Roman Weaponry and Armor

These finds paint a vivid picture of the cultural and economic interactions between the Roman occupants and the local populations.

While much of the Antonine Wall’s original structure has been lost to time, the enduring remnants, along with the archaeological discoveries and ongoing preservation efforts, ensure that its legacy continues to captivate and educate.

What Was the Difference between Hadrian’s Wall and Antonine Wall?

The Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall, two of Roman Britain’s most formidable frontier constructions, served similar purposes as northern defenses of the empire but differed significantly in their construction, geography, and historical roles.

Construction Materials and Techniques

Hadrian’s Wall, built under Emperor Hadrian’s reign starting in AD 122, was primarily constructed of stone, reflecting its permanence as a defensive structure. The use of stone made the wall robust and durable, capable of withstanding the harsh weather conditions and potential assaults for centuries.

In contrast, the Antonine Wall, constructed around 20 years later, was primarily built from turf stacked on a stone foundation. This method was quicker and utilized local materials, but it resulted in a less durable structure that did not endure as well as Hadrian’s stone wall.

Geographical Location

Geographically, the two walls occupied strategic positions in Britain but with notable differences. Hadrian’s Wall spanned the narrowest part of the island from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, creating a defensible barrier that took advantage of the natural terrain.

The Antonine Wall was situated further north, running across the Central Belt of Scotland between the Firth of Forth and Clyde Canal.

This location, while advantageous for short-term military expeditions, proved more challenging to defend and sustain in the long term due to its proximity to the unconquered territories of the Caledonian tribes.

In terms of length and scope, the Antonine Wall, at approximately 60 kilometers (about 37 miles) in length, was shorter than Hadrian’s Wall, which stretched about 117 kilometers (about 73 miles).

The shorter length of the Antonine Wall reflected a strategic attempt to control a narrower part of the island, though its effectiveness was compromised by the aggressive stance of the local tribes and the logistical difficulties of maintaining a frontier so far from the main Roman bases in southern Britain.

Purpose and Symbolism

Both walls served the purpose of marking the northwest frontier of Roman Britain, but they also symbolized the Roman Empire’s reach and authority. Hadrian’s Wall was as much a symbol of Roman power as it was a functional military barrier, incorporating significant forts, milecastles, and turrets along its length.

The Antonine Wall, while also a display of Roman ambition, was part of a more aggressive push northward and represented a brief period of expansion under Antoninus Pius.

Legacy and Preservation

The differing materials and construction techniques have significantly impacted the preservation and visibility of the two walls today. Hadrian’s Wall remains more prominent in the landscape, with large sections still standing and numerous ruins of forts and settlements to explore.

The Antonine Wall, primarily made of turf, has left fewer physical remains, though its path is still traceable, and key sites have been excavated, revealing a wealth of archaeological finds.

The Enduring Significance of the Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall, once a symbol of Roman ambition and engineering prowess on the northern frontier of Britain, remains a captivating monument that speaks volumes about the Roman Empire’s reach and the complexities of its interactions with the lands and peoples it sought to control.

Through the remnants of this ancient barrier and the ongoing efforts to study, preserve, and celebrate it, we gain invaluable insights into the military, cultural, and political nuances of Roman Britain.

The story of the Antonine Wall is one of ambition, adaptation, and eventual retreat, reflecting the ebb and flow of Roman influence in a distant and challenging territory.

It highlights the empire’s capacity for extraordinary feats of engineering and organization, as well as the limits of its power in the face of persistent resistance and logistical challenges.

The wall’s construction, brief period of use, and subsequent abandonment offer a poignant reminder of the impermanence of political and military endeavors, even those as formidable as the Roman Empire.