Chronicle of the Emperors

The Roman state began as a semi-mythical and small-scale monarchy in the 10th century BC. It later prospered as an expansionist republic from 509 BC onwards. Then, in 27 BC, it became an empire. Its leaders, the emperors of Rome, went on to become some of the most powerful heads of state in history. Here is a list of all the Roman emperors in Order, from Julius Caesar to Romulus Augustus.

Table of Contents

Complete List of All Roman Emperors in Order

The Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 BC – 68 AD)

- Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD)

- Tiberius (14 AD – 37 AD)

- Caligula (37 AD – 41 AD)

- Claudius (41 AD – 54 AD)

- Nero (54 AD – 68 AD

The Year of the Four Emperors (68 – 69 AD)

The Flavian Dynasty (69 AD – 96 AD)

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (96 AD – 192 AD)

- Nerva (96 AD – 98 AD)

- Trajan (98 AD – 117 AD)

- Hadrian (117 AD – 138 AD)

- Antoninus Pius (138 AD – 161 AD)

- Marcus Aurelius (161 AD – 180 AD) & Lucius Verus (161 AD – 169 AD)

- Commodus (180 AD – 192 AD)

The Year of the Five Emperors (193 AD – 194 AD)

- Pertinax (193 AD)

- Didius Julianus (193 AD)

- Pescennius Niger (193 AD – 194 AD)

- Clodius Albinus (193 AD – 197 AD)

The Severan Dynasty (193 AD – 235 AD)

- Septimius Severus (193 AD – 211 AD)

- Caracalla (211 AD – 217 AD)

- Geta (211 AD)

- Macrinus (217 AD – 218 AD)

- Diaumenian (218 AD)

- Elagabalus (218 AD – 222 AD)

- Severus Alexander (222 AD – 235 AD)

The Crisis of the Third Century (235 AD – 284 AD)

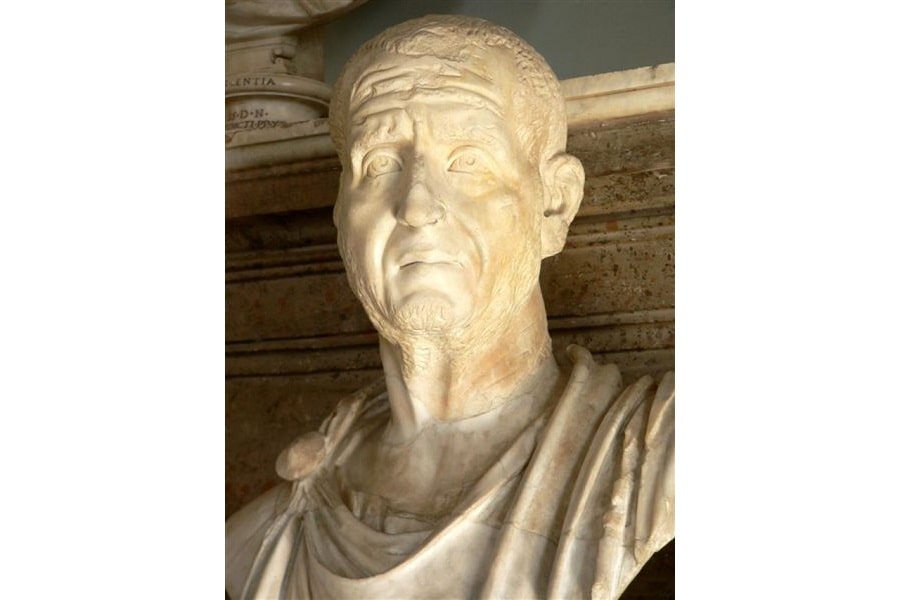

- Maximinus Thrax (235 AD – 238 AD)

- Gordian I (238 AD)

- Gordian II (238 AD)

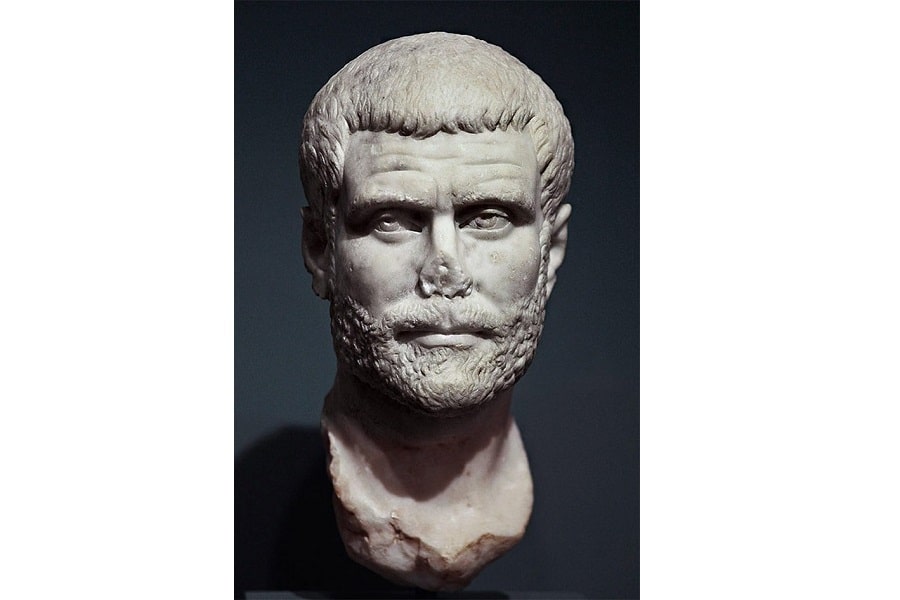

- Pupienus (238 AD)

- Balbinus (238 AD)

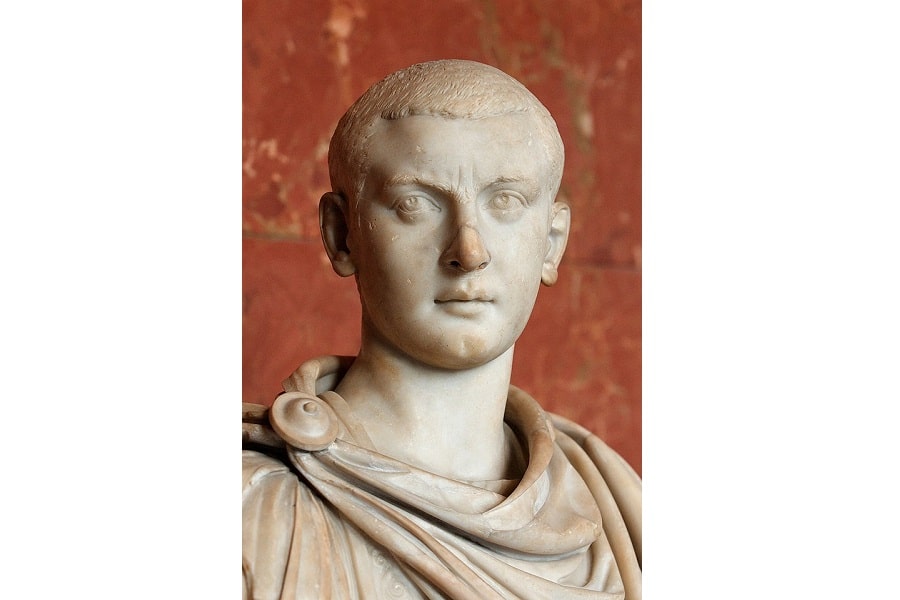

- Gordian III (238 AD – 244 AD)

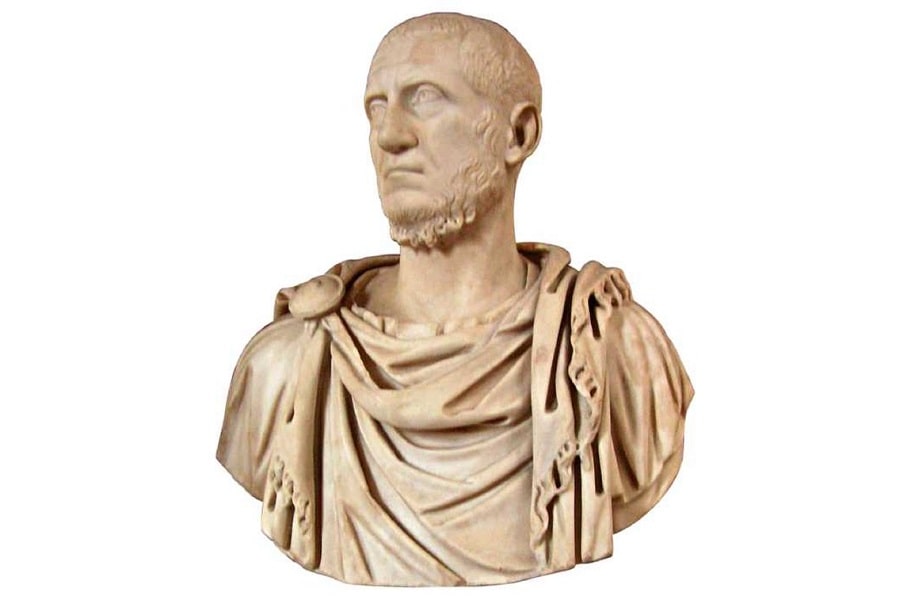

- Phillip I (244 AD – 249 AD)

- Phillip II (247 AD – 249 AD)

- Decius (249 AD – 251 AD)

- Herrenius Etruscus (251 AD)

- Trebonianus Gallus (251 AD – 253 AD)

- Hostilian (251 AD)

- Volusianus (251 – 253 AD)

- Aemilianus (253 AD)

- Sibannacus (253 AD)

- Valerian (253 AD – 260 AD)

- Gallienus (253 AD – 268 AD)

- Saloninus (260 AD)

- Claudius Gothicus (268 AD – 270 AD)

- Quintillus (270 AD)

- Aurelian (270 AD – 275 AD)

- Tacitus (275 AD – 276 AD)

- Florianus (276 AD)

- Probus (276 AD – 282 AD)

- Carus (282 AD – 283 AD)

- Carinus (283 AD – 285 AD)

- Numerian (283 AD – 284 AD)

The Tetrarchy (284 AD – 324 AD)

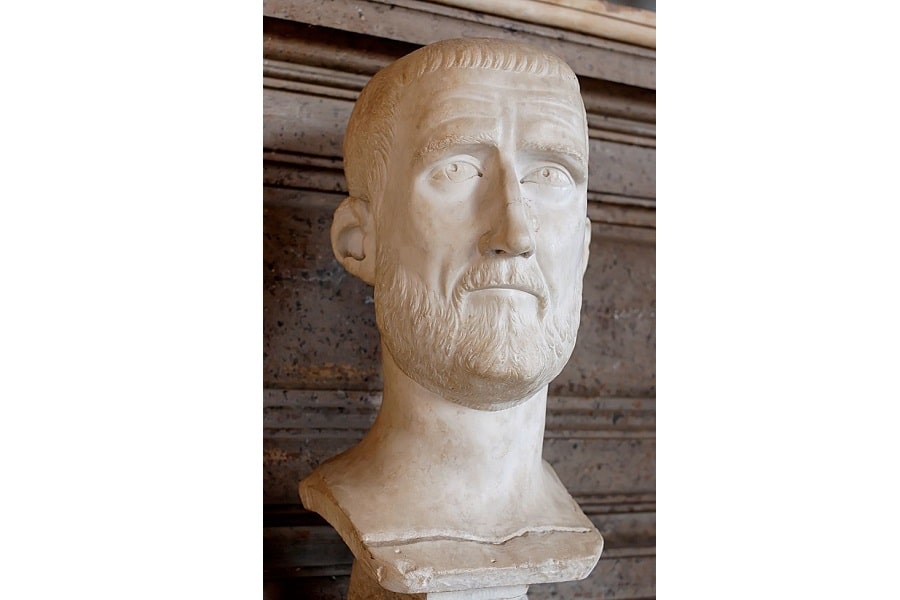

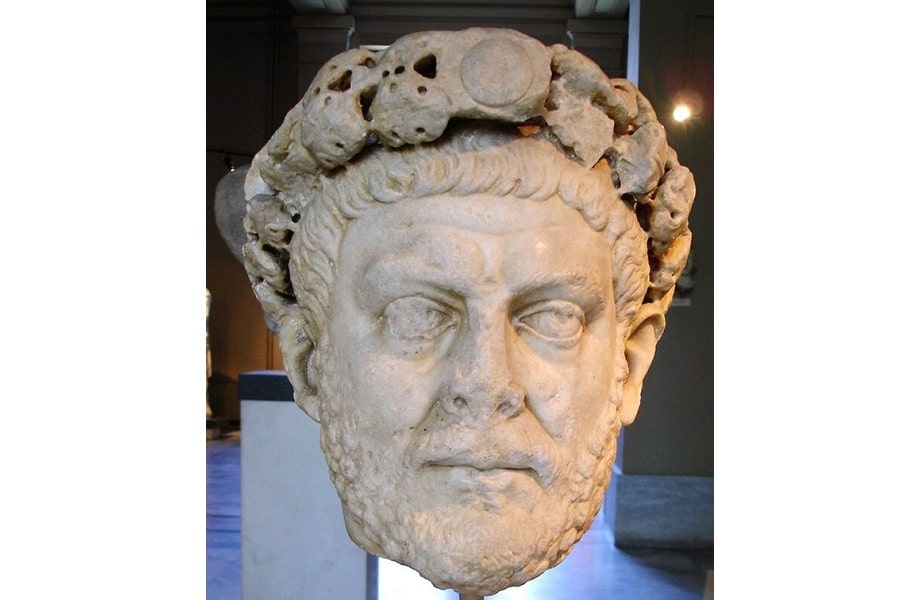

- Diocletian (284 AD – 305 AD)

- Maximian (286 AD – 305 AD)

- Galerius (305 AD – 311 AD)

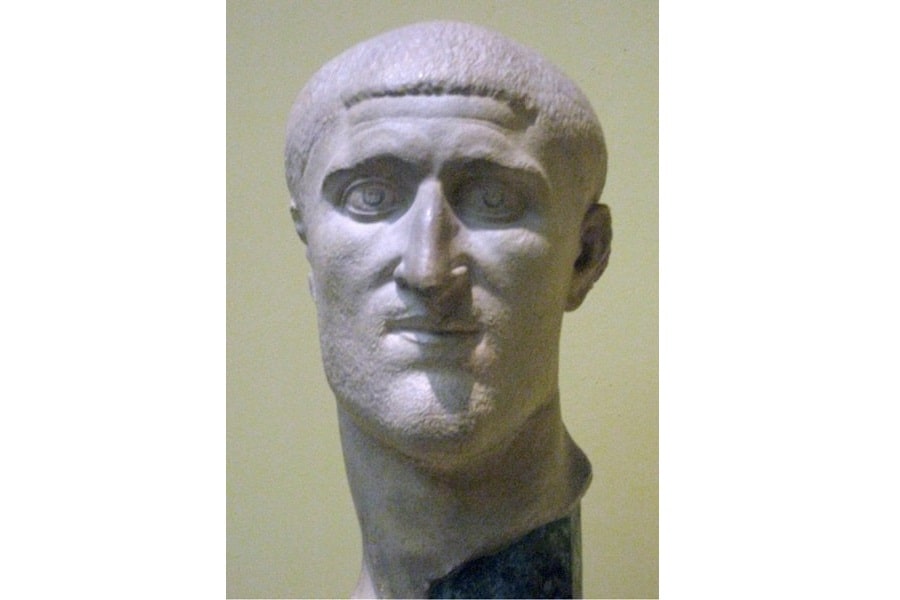

- Constantius I (305 AD – 306 AD)

- Severus II (306 AD – 307 AD)

- Maxentius (306 AD – 312 AD)

- Licinius ( 308 AD – 324 AD)

- Maximinus II (310 AD – 313 AD)

- Valerius Valens (316 AD – 317 AD)

- Martinian (324 AD)

The Constantinian Dynasty (306 AD – 364 AD)

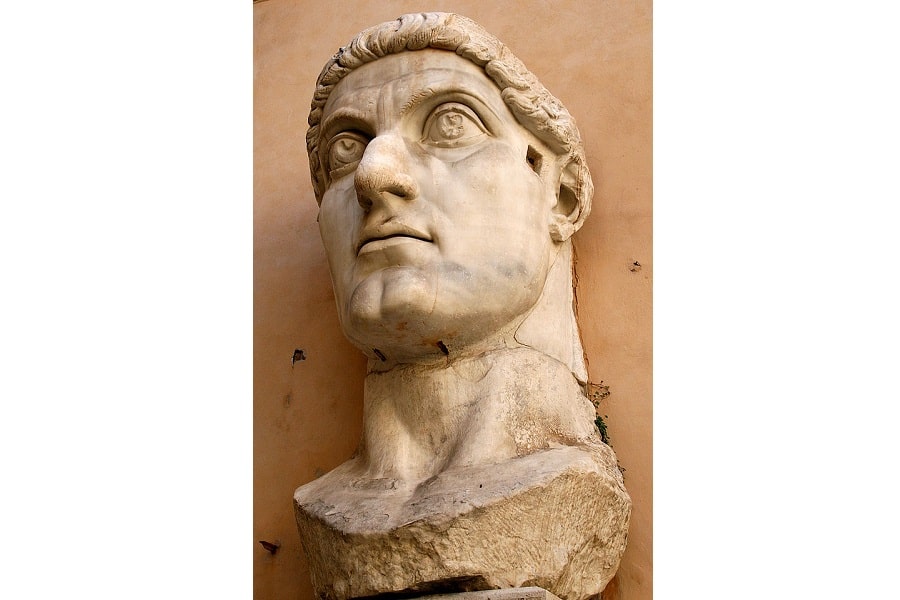

- Constantine I (306 AD – 337 AD)

- Constantine II (337 AD – 340 AD)

- Constans I (337 AD – 350 AD)

- Constantius II (337 AD – 361 AD)

- Magnentius (350 AD – 353 AD)

- Nepotianus (350 AD)

- Vetranio (350 AD)

- Julian (361 AD – 363 AD)

- Jovian (363 AD – 364 AD)

The Valentinian Dynasty (364 AD – 394 AD)

- Valentinian I (364 AD – 375 AD)

- Valens (364 AD – 378 AD)

- Procopius (365 AD – 366 AD)

- Gratian (375 AD – 383 AD)

- Magnus Maximus (383 AD – 388 AD)

- Valentinian II (388 AD – 392 AD)

- Eugenius (392 AD – 394 AD)

The Theodosian Dynasty (379 AD – 457 AD)

- Theodosius I (379 AD – 395 AD)

- Arcadius (395 AD – 408 AD)

- Honorius (395 AD – 423 AD)

- Constantine III (407 AD – 411 AD)

- Theodosius II (408 AD – 450 AD)

- Priscus Attalus (409 AD – 410 AD)

- Constantius III (421 AD)

- Johannes (423 AD – 425 AD)

- Valentinian III (425 AD – 455 AD)

- Marcian (450 AD – 457 AD)

Leo I and the Last Emperors in the West (455 AD – 476 AD)

- Leo I (457 AD – 474 AD)

- Petronius Maximus (455 AD)

- Avitus (455 AD – 456 AD)

- Majorian (457 AD – 461 AD)

- Libius Severus (461 AD – 465 AD)

- Anthemius (467 AD – 472 AD)

- Olybrius (472 AD)

- Glycerius (473 AD – 474 AD)

- Julius Nepos (474 AD – 475 AD)

- Romulus Augustus (475 AD – 476 AD)

The First (Julio-Claudian) Dynasty (27 BC – 68 AD)

The Emergence of the Principate under Augustus (44 BC – 27 BC)

Born in 63BC as Gaius Octavius, he was related to Julius Caesar, whose famous legacy he built on to become Emperor. This is because Julius Caesar was the last in a line of warring aristocratic generals who pushed the limits of republican power to its breaking point and laid the groundwork for Augustus to become Emperor.

After defeating his rival Pompey, Julius Caesar – who had adopted Octavius – declared himself “dictator for life,” to the ire of many contemporary senators. Whilst this was really an inevitable outcome of the endless civil wars that beset the Late Republic, he was killed for such bold impertinence by a large group of senators in 44 BC.

This cataclysmic event brought Augustus/Octavian to the fore, as he went about avenging his adopted father’s assassination and cementing his power base. After this he became embroiled in a civil war with Mark Antony, his adopted father’s old right-hand man.

He was ruthlessly successful in both endeavors to the point that by 31 BC he was the most powerful man in the Roman world, with little to no opposition left. In order to avoid the fate of his adopted father, however, he feigned the resignation of his position and “restored the republic” to the senate and people in 27 BC.

As he likely had expected (and calculated) the senate granted him extraordinary powers which allowed him to reign supreme over the Roman state. He was also offered the title “Augustus” which had semi-divine connotations. As such, the position of princeps (aka Emperor) was founded.

Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD)

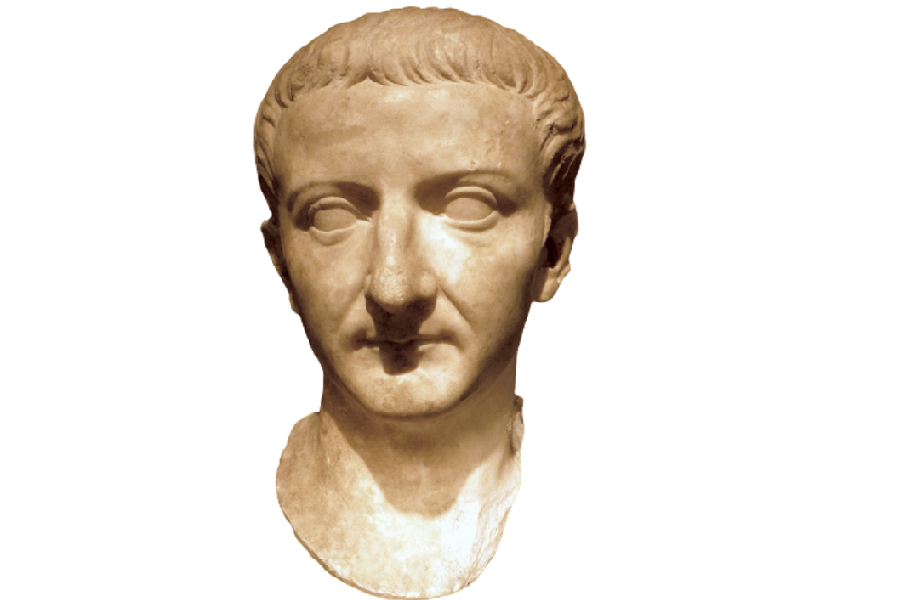

Tiberius (14 AD – 37 AD)

Augustus’s successor Tiberius is widely depicted in the sources as a disagreeable and disinterested ruler, who did not get on well with the senate and ruled reluctantly over the empire. Whilst he had been pivotal to the expansionism of his predecessor Augustus, he engaged in little military activity when he took up the position of Princeps.

After the death of his son Drusus, Tiberius left Rome for the island of Capri in 26 AD, after which he left the administration of the empire in the hands of his Praetorian prefect Sejanus. This led to a power grab on the latter’s part which was ultimately unsuccessful but temporarily rocked politics in Rome.

By the time of his death in 37 AD, a successor had not been properly named and little change had been brought to the empire’s borders, except some expansion into Germania. It is reported that he was actually murdered by a prefect loyal to Caligula, who wished to hasten the latter’s succession.

READ MORE: Tiberius

Caligula (37 AD – 41 AD)

Caligula is commonly referred to as one of the worst Roman Emperors, because of his depraved and apparently insane behavior. Although the beginning of his reign was characterized by widespread munificence, an apparent attempt on his life made him devolve into a capricious and paranoid tyrant.

Within this sharp shift of rulership, there were some positive political reforms offset by financial mismanagement. There was also a considerable amount of public works, as well as expansion of the empire into new areas of North Africa.

Nonetheless, his ruthless bouts of paranoia and consequent killings of senators and bureaucrats made his assassination in 41 AD at the hands of a praetorian guard look inevitable.

READ MORE: Caligula

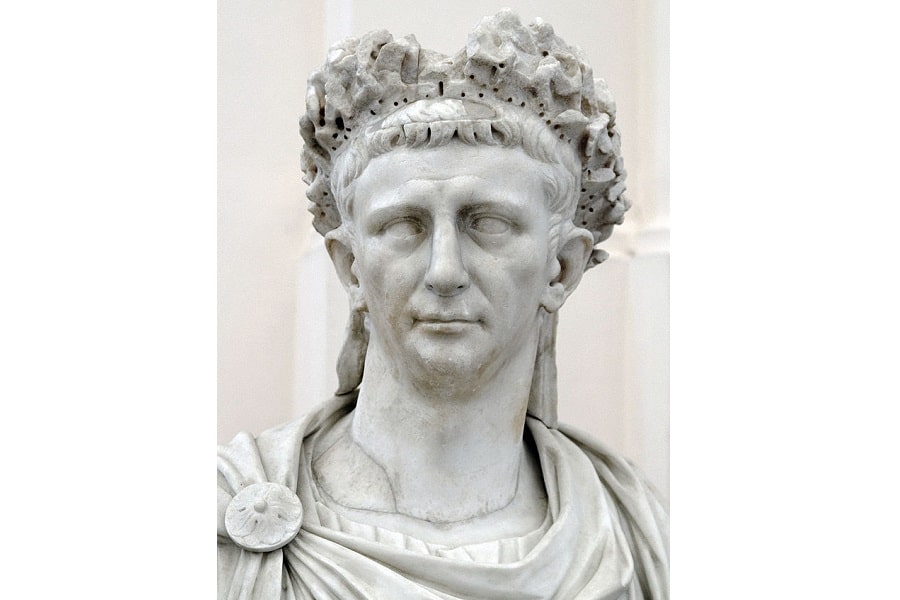

Claudius (41 AD – 54 AD)

Most famous perhaps because of his disabilities, Emperor Claudius proved himself a very competent administrator, even if was apparently forced into position by the praetorian guard, who sought a new figurehead after their murder of Caligula.

During his reign, there was general peace across the empire, good management of finances, progressive legislation, and a considerable expansion of the empire – particularly through the first proper conquest of parts of Britain (after Julius Caesar’s earlier expedition).

The ancient sources however present Claudius as a passive figure at the helm of government, controlled by those around him. Furthermore, they strongly suggest or outright claim that he was murdered by his third wife Agrippina, who subsequently propped her son Nero up onto the throne.

READ MORE: Claudius

Nero (54 AD – 68 AD)

Like Caligula, Nero was remembered most for his infamy, epitomized in the fable of him nonchalantly playing his fiddle as the city of Rome burnt in 64 AD.

Upon coming into power at a young age, he was initially guided by his mother and advisors (including the Stoic philosopher Seneca). However, he eventually killed his mother and “removed” many of his most competent advisors, including Seneca.

After this, Nero’s reign was characterized by his increasingly erratic, spendthrift, and violent behavior, culminating in him posturing himself as a god. Soon after some serious rebellions broke out in the frontier provinces, Nero ordered his servant to kill him in 68 AD.

READ MORE: Nero

The Year of the Four Emperors (68 AD – 69 AD)

In the Year 69 AD, after the fall of Nero, three different figures briefly acclaimed themselves emperor, before the fourth, Vespasian, brought the chaotic and violent period to an end, establishing the Flavian Dynasty.

Galba (68 AD – 69 AD)

Galba was the first to be proclaimed emperor (actually in 68 AD) by his troops, whilst Nero was still alive. After Nero’s assisted suicide, Galba was properly proclaimed emperor by the senate, but was evidently very unfit for the job, displaying a basic lack of expediency, in who to placate and who to reward. For his ineptitude, he was murdered at the hands of his successor Otho.

READ MORE: Galba

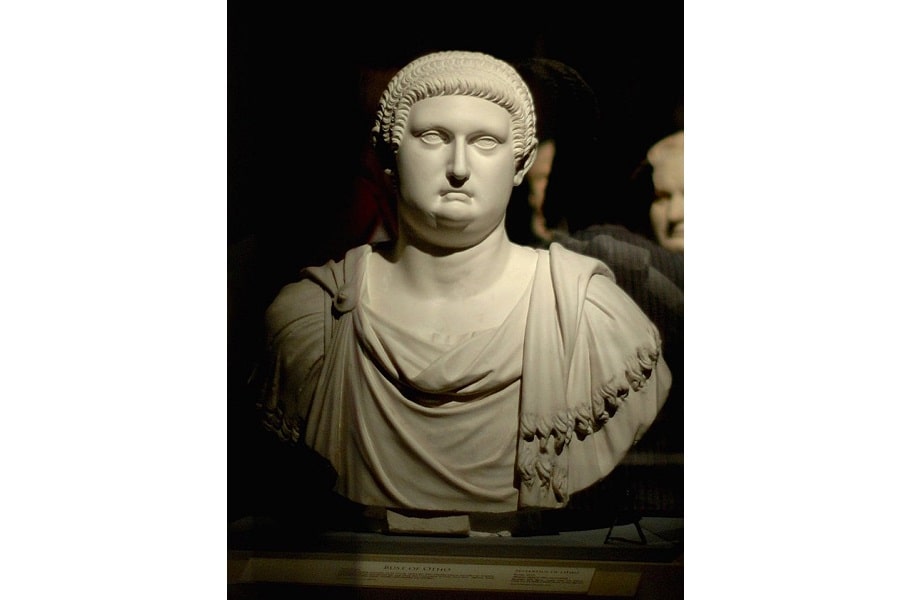

Otho (68 – 69 AD)

Otho had been a loyal commander for Galba and had seemingly resented the latter’s failure to promote him as his heir. He only managed to rule for three months and his reign was mostly constituted by his civil war with another claimant to the Principate, Vitellius.

After Vitellius defeated Otho decisively, at the First Battle of Bedriacum, the latter committed suicide, ending his extremely short reign.

READ MORE: Otho

Vitellius (69 AD)

Although he only ruled for 8 months, Vitellius is generally considered to be one of the worst Roman emperors, because of his various excesses and indulgences (primarily his inclinations towards luxury and cruelty). He instituted some progressive bits of legislation but was quickly challenged by the general Vespasian in the east.

Vitellius’s armies were defeated decisively by the robust forces of Vespasian at the Second Battle of Bedriacum. Rome was subsequently besieged and Vitellius was hunted down, his body dragged through the city, decapitated, and thrown in the river Tiber.

READ MORE: Vitellius

The Flavian Dynasty (69 AD – 96 AD)

As Vespasian won out amidst the internecine warfare of the Year of the Four Emperors, he managed to restore stability and establish the Flavian Dynasty. Notably, his accession and the reigns of his sons proved that an emperor could be made outside of Rome and that military might was paramount.

Vespasian (69 AD – 79 AD)

Seizing power with the support of the eastern legions in 69 AD, Vespasian was the first emperor from an Equestrian family – the lower aristocratic class. Rather than the courts and palaces of Rome, his reputation had been established on the battlefields of the frontiers.

There were rebellions early on in his reign in Judaea, Egypt, and both Gaul and Germania, yet all of these were decisively put down. To cement his authority and the Flavian Dynasty’s right to rule, he focused on a propaganda campaign through coinage and architecture.

After a relatively successful rule, he died in June 79 AD, unusually for a Roman emperor, with no real rumors of conspiracy or assassination.

READ MORE: Vespasian

Titus (79 AD – 81 AD)

Titus was the elder son of Vespasian who accompanied his father on a number of his military campaigns, particularly in Judaea as they both faced a fierce revolt there beginning in 66AD. Before becoming emperor he had acted as head of the praetorian guard and apparently had an affair with the Jewish queen Berenice.

Although his reign was relatively short, it was punctuated by the completion of the famous Colosseum, as well the eruption of Mt Vesuvius, and the second legendary fire of Rome. After a fever, Titus died in September 81AD.

READ MORE: Titus

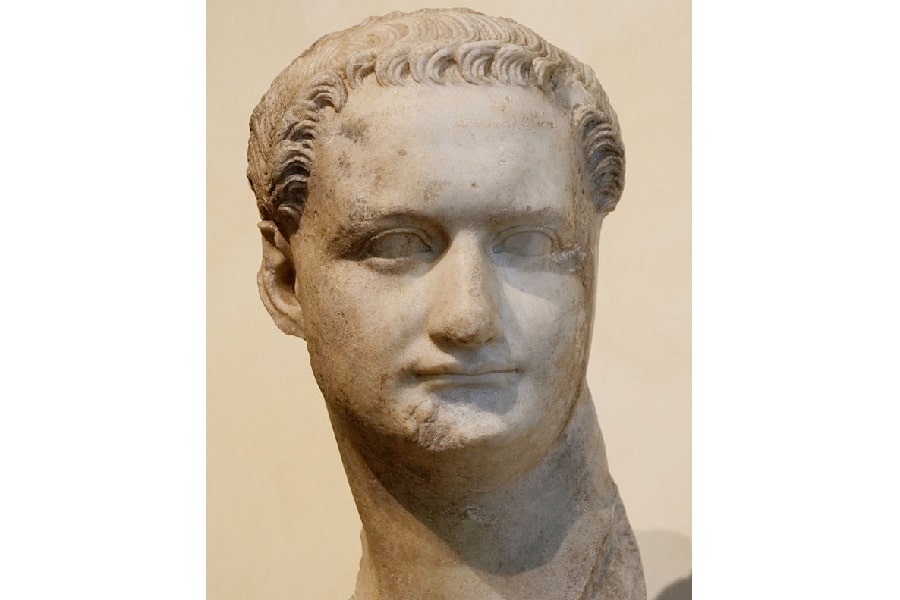

Domitian (81 AD – 96 AD)

Domitian joins the likes of Caligula and Nero, as one of the most notorious Roman Emperors, mainly because he was so at odds with the senate. He seems to have seen them primarily as a nuisance and an obstacle that he had to overcome in order to properly rule.

As such, Domitian is infamous for his micromanagement of various areas of the administration of the empire, particularly in coinage and legislation. He is perhaps more infamous for his slew of executions that he ordered against various senators, often aided by equally infamous informers, known as “delatores.”

He was eventually murdered for his paranoid killings, by a group of court officials, in 96 AD, ending the Flavian Dynasty in the process.

READ MORE: Domitian

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (96 AD – 192 AD)

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty is famed for bringing in and fostering the “Golden Age” of the Roman Empire. The responsibility for such an accolade lies on the shoulders of five of these Nerva-Antonines, known in Roman history as the “Five Good Emperors” – which included Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.

Quite uniquely as well, these emperors succeeded each other through adoption, rather than bloodline – up until Commodus, who brought the dynasty and empire down into ruin.

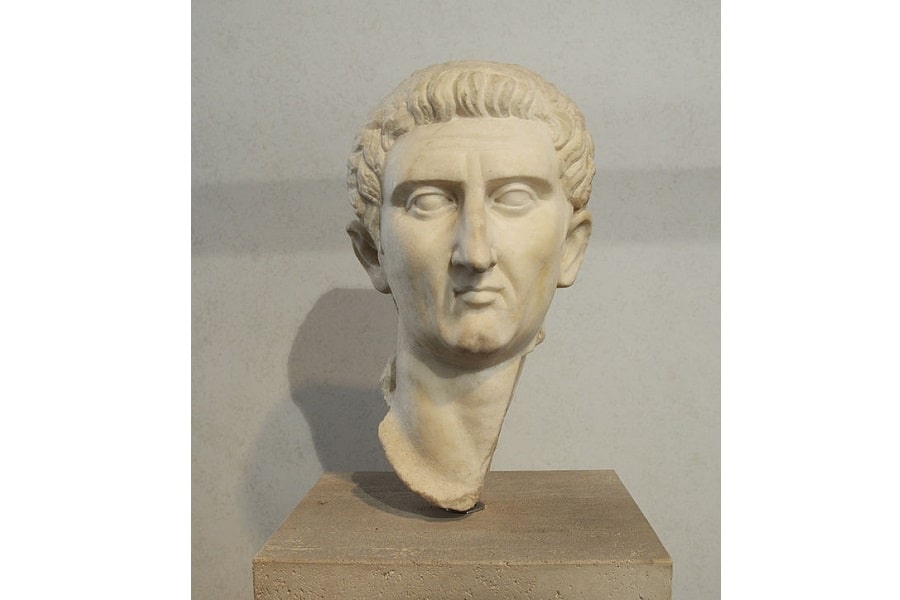

Nerva (96 AD – 98 AD)

After the assassination of Domitian, the Roman senate and aristocracy wanted to claw back their power over political affairs. As such, they nominated one of their veteran senators – Nerva – for the role of the emperor in 96 AD.

However, in his brief reign in charge of the empire, Nerva was beset by financial difficulties and the inability to properly assert his authority over the military. This led to a sort of coup in the capital that forced Nerva to pick a more authoritative heir in Trajan, shortly before his death.

READ MORE: Nerva

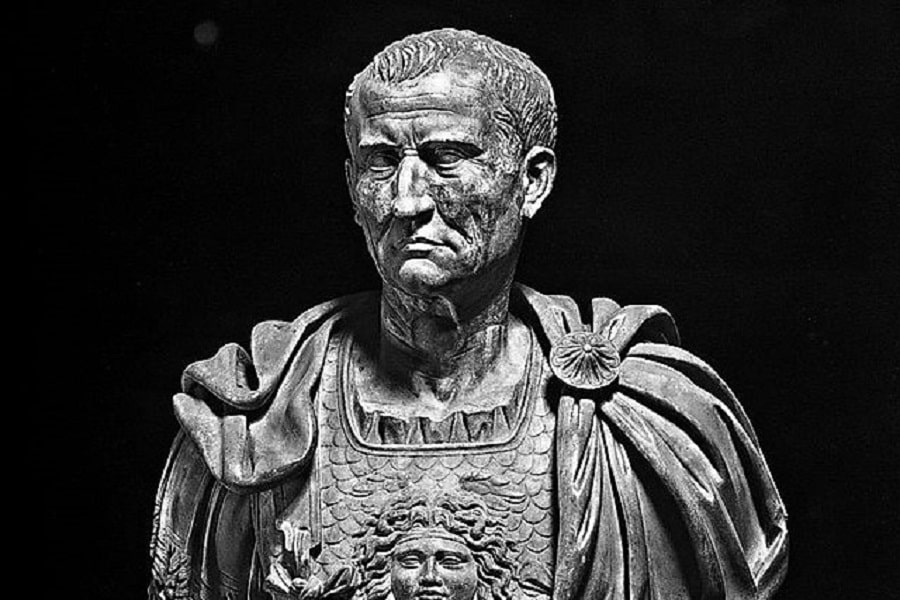

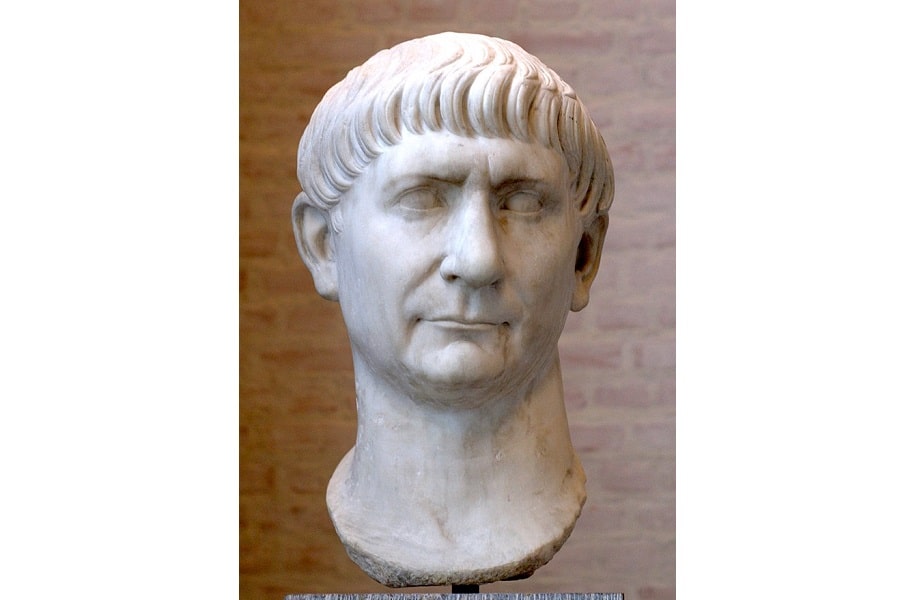

Trajan (98 AD – 117 AD)

Trajan has been immortalized in history as the “Optimus Princeps” (“best emperor”), illustrating his fame and ability to rule. Where his predecessor Nerva fell short, Trajan seemed to excel – particularly in military matters, where he expanded the empire to its largest-ever extent.

He also commissioned and completed a prodigious building program in the city of Rome and throughout the empire, as well as being famous for augmenting welfare programs that his predecessor had seemingly started. By the time of his death, the image of Trajan was held up as a model emperor for all subsequent ones to follow.

READ MORE: Trajan

Hadrian (117 AD – 138 AD)

Hadrian was and is received as somewhat of an ambiguous emperor, since, even though he was one of the “Five Good Emperors,” he seemed to scorn the senate, ordering a number of spurious executions against its members. However, in the eyes of some contemporaries, he made up for this with his ability for administration and defense.

Whereas his predecessor Trajan had expanded Rome’s frontiers, Hadrian decided to instead begin fortifying them – even in some cases by pushing them back. He was also famous for bringing the beard back into style for Roman elites and for his constant traveling around the empire and its frontiers.

READ MORE: Hadrian

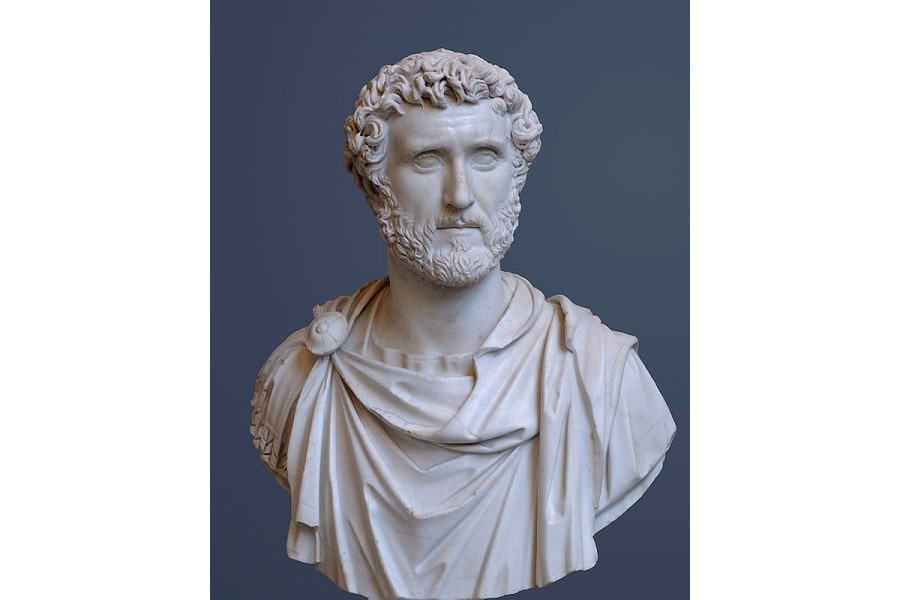

Antoninus Pius (138 AD – 161 AD)

Antoninus is an emperor without much historical documentation left to us. However, we know that his reign was seen as one of generally undisturbed peace and felicity, whilst he was named Pius because of his generous praise for his predecessor Hadrian.

Of note, he was also known to be a very shrewd manager of finances and politics, maintaining stability across the empire and setting up the principate well for his successors.

READ MORE: Antoninus Pius

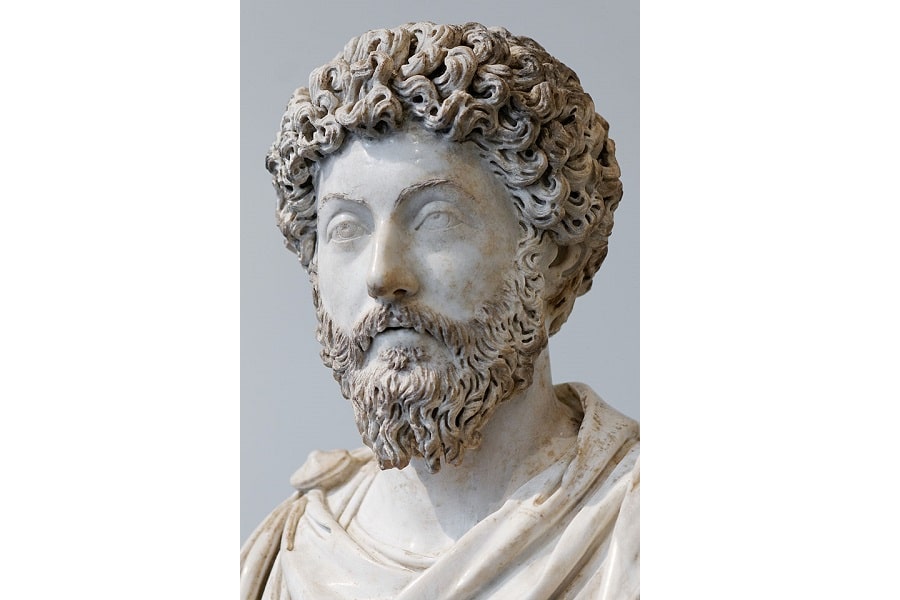

Marcus Aurelius (161 AD – 180 AD) & Lucius Verus (161 AD – 169 AD)

Both Marcus and Lucius had been adopted by their predecessor Antoninus Pius, in what had become a trademark of the Nerva-Antonine succession system. Although each emperor up until Marcus Aurelius did not have a blood heir to actually inherit the throne, it was also seen as politically prudent to promote the “best man,” rather than a pre-ordained son or relative.

In a novel twist to this, both Marcus and Lucius were adopted and ruled jointly, until the latter died in 169 AD. Whilst Marcus is commonly seen as one of the best Roman emperors, the joint reign of both figures was beset by many conflicts and issues for the empire, especially in the north-eastern frontiers of Germania, and war with the Parthian Empire in the east.

Lucius Verus died soon after becoming involved in the Marcommanic War, perhaps of the Antonine Plague (which broke out during their reign). Marcus spent much of his reign engaged with the Marcommanic threat but famously found time to write his Meditations – now a contemporary classic of Stoic philosophy.

Marcus in turn died in 182 AD, near the frontier, leaving his son Commodus as heir, against the convention of previously adopted successions.

READ MORE: Marcus Aurelius

READ MORE: Lucius Verus

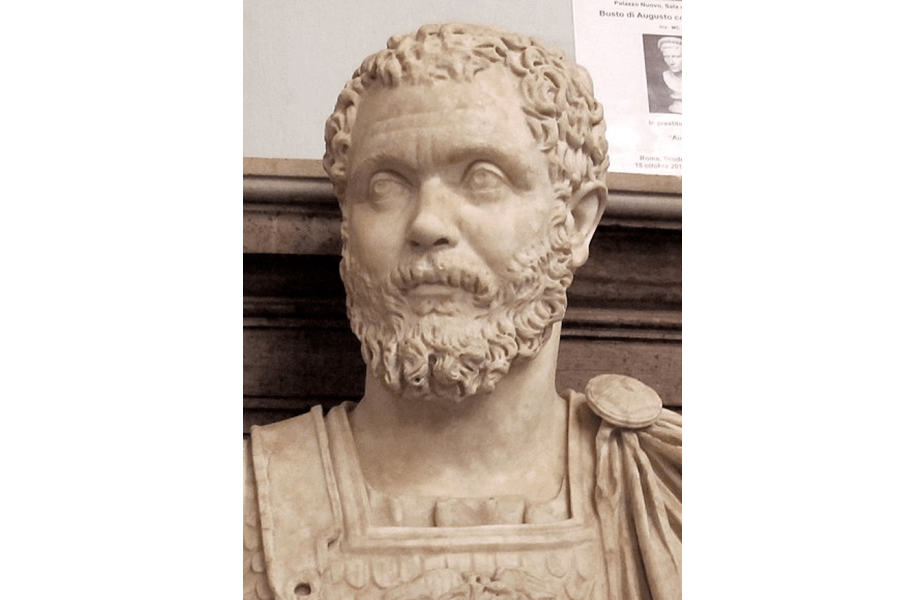

Commodus (180 AD – 192 AD)

The accession of Commodus proved to be a turning point for the Nerva-Antonine Dynasty and its apparently unparalleled rule. Although he had been raised by the most philosophical of all emperors and had even ruled with him jointly for some time, he seemed utterly unfit for the role.

Not only did he defer many of the responsibilities of government to his confidants, but he also centered a personality cult around himself as a god-emperor, as well as performing as a gladiator in the Colosseum – something that was sharply looked down upon for an emperor.

After conspiracies against his life, he also became increasingly paranoid with the senate and ordered a slew of executions, whilst his confidants plundered the wealth of their peers. After such a disappointing turn of events in the dynasty, Commodus was assassinated at the hands of a wrestling partner in 192 AD – the deed ordered by his wife and praetorian prefects.

READ MORE: Commodus: The First Ruler of the End of Rome

The Year of the Five Emperors (193 AD – 194 AD)

The Roman historian Cassius Dio famously stated that the death of Marcus Aurelius coincided with the Roman Empire’s decline “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust.” This is because the calamitous reign of Commodus and the period of Roman History that followed it have been seen as one of constant decline.

This is encapsulated by the chaotic year 193, wherein five different figures claimed the throne of the Roman Empire. Each claim was contested and so the five rulers fought against each in civil war, until Septimius Severus finally emerged as sole ruler in 197 AD.

Pertinax (193 AD)

Pertinax was serving as Urban Prefect – a senior administrative role in the city of Rome – when Commodus was murdered on the 31st of December 192 AD. His reign and life thereafter were very short-lived. He reformed the currency and aimed to discipline the increasingly unruly praetorian guard.

However, he had failed to properly pay the military and had his palace stormed after just 3 months in charge, resulting in his death.

READ MORE: Pertinax

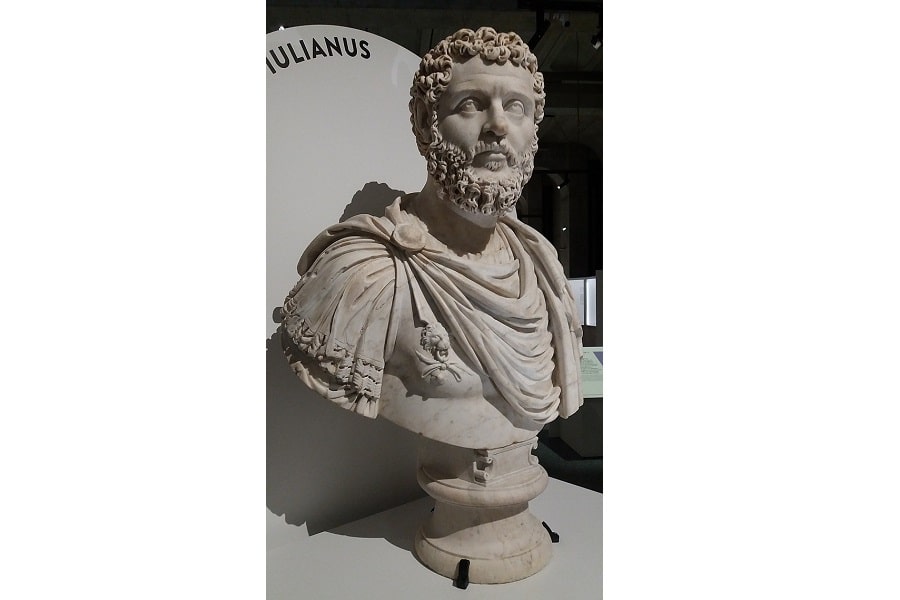

Didius Julianus (193 AD)

Julianus’s reign was even shorter than his predecessors – lasting only 9 weeks. He also came to power in a notorious scandal – by buying the principate from the praetorian guard, who had incredulously put it up for sale to the highest bidder after Pertinax’s death.

For this, he was a deeply unpopular ruler, who was very quickly opposed by three rival claimants in the provinces – Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus, and Septimius Severus. Septimius represented the most immediate threat in the Near East, who had already allied himself with Clodius, making the latter his “caesar” (junior emperor).

Julianus tried to have Septimius killed, but the attempt failed miserably, as Septimius moved closer and closer to Rome, until a soldier killed the incumbent emperor Julianus.

READ MORE: Julianus

Pescennius Niger (193 AD – 194 AD)

Whilst Septimius Severus had been proclaimed emperor in Illyricum and Pannonia, Clodius in Britain and Gaul, Niger had been proclaimed emperor further east in Syria. As Didius Julianus was removed as a threat and Septimius was made emperor (with Albinus as his junior emperor), Septimius headed east to defeat Niger.

After three major battles in 193 and early 194 Niger was defeated and died in battle, with his head being transported back to Severus in Rome.

READ MORE: Pescennius Niger

Clodius Albinus (193 – 197 AD)

Now that both Julianus and Niger had been defeated, Septimius began preparing to defeat Clodius and make himself the sole emperor. The rift between the two nominal co-emperors opened up when Septimius reportedly named his son as heir in 196 AD, to the dismay of Clodius.

After this, Clodius mustered his forces in Britain, crossing the channel into Gaul and defeating some of Septimius’s forces there. However, in 197 AD at the battle of Lugdunum, Clodius was killed, his forces routed, and Septimius left in charge of the empire – subsequently establishing the Severan Dynasty.

READ MORE: Albinus

The Severan Dynasty (193 AD – 235 AD)

Having defeated all of his rivals and established himself as the sole ruler of the Roman world, Septimius Severus had brought stability back to the Roman Empire. The Dynasty that he established, whilst it tried – quite explicitly – to emulate the success of the Nerva-Antonine Dynasty and model itself on its predecessors, fell short in this respect.

Under the Severans, a trend that saw the increasing militarization of the empire, its elite, and the role of the Emperor was greatly accelerated. This trend helped to begin the marginalization of the old aristocratic (and senatorial) elite.

Moreover, the reigns which constitute the Severan Dynasty suffered from civil wars and often quite ineffective emperors.

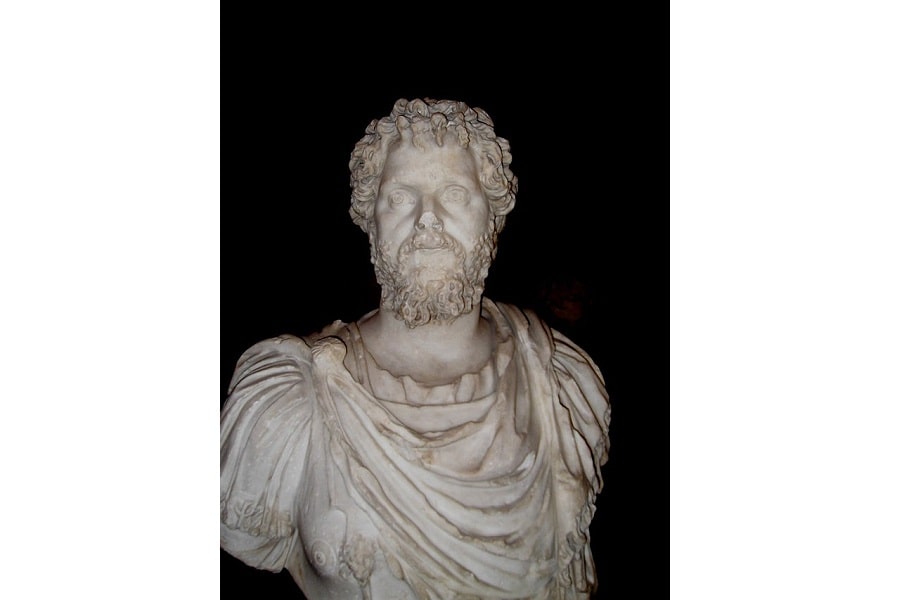

Septimius Severus (193 AD – 211 AD)

Born in North Africa, Septimius Severus rose to power in untypical circumstances for the day, although not as untypical as some might think. He was raised in an aristocratic family with links to the elite in Rome, as was the case in many provincial cities at this point.

After establishing himself as emperor, he followed in the footsteps of Trajan as a great expander of the empire. He also began to center power more on the figure of the emperor, within a framework of military elites and officials, as well as investing in the periphery regions more than most previous emperors had.

During one of his campaigns in Britain, he died in 211 AD, bequeathing the empire to his sons Caracalla and Geta to rule jointly.

READ MORE: Septimius Severus: The First African Emperor of Rome

Caracalla (211 AD – 217 AD) and Geta (211 AD)

Caracalla ignored the command given to him by his father to keep peace with his brother Geta and had him murdered later the same year – in their mother’s arms. This brutality was followed by other massacres that were carried out during his reign in Rome and in the provinces.

As emperor, he seems disinterested in the administration of the empire and deferred many responsibilities to his mother Julia Domna. Besides this, his reign is notable for the construction of a large bathhouse in Rome, some reforms in the currency, and a failed invasion of Parthia which led to Caracalla’s death in 217 AD.

READ MORE: Caracalla

READ MORE: Geta

Macrinus (217 AD – 218 AD) and Diadumenian (218 AD)

Macrinus had been the praetorian prefect of Caracalla and was responsible for organizing his assassination to avoid his own murder. He was also the first emperor who was born from the equestrian, rather than the senatorial class. Moreover, he was the first emperor never to actually visit Rome.

This is partly because he was beset by problems with Parthia and Armenia in the East, as well as the short duration of his reign. Whilst he had named his young son Diadumenian as co-ruler in order to help secure his power (through clear continuity) they were thwarted by Caracalla’s aunt, who schemed to have her grandson Elagabalus placed on the throne.

In the midst of unrest in the empire owing to certain reforms initiated by Macrinus, a civil war broke out in Elagabalus’s cause. Macrinus was soon defeated at Antioch in 218 AD, after which his son Diadumenian was hunted down and executed.

READ MORE: Macrinus

Elagabalus (218 AD – 222 AD)

Elagabalus was in fact born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, later changing it to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, before he received his nickname, Elagabalus. He was raised to the throne by his grandmother’s militaristic coup when he was only 14 years old.

His subsequent reign was marred by sex scandals and religious controversy as Elagabalus replaced Jupiter as the supreme god with his own favorite sun god, Elagabal. He also engaged in many indecent sexual acts, marrying four women, including a sacrosanct vestal virgin, who was not supposed to be married or engaged with intimately by anyone.

For such indecency and license, Elagabalus was murdered under the orders of his grandmother, who had clearly become disillusioned with his incompetence.

READ MORE: Elagabalus

Severus Alexander (222 AD – 235 AD)

Elagabalus was replaced by his cousin, Severus Alexander, under whom the empire managed to retain some stability, until his own assassination, which corresponded with the beginning of the chaotic period known as the Crisis of the Third Century.

For most of Severus’s reign, the empire witnessed peace across the empire, with improved legal practice and administration. There were however growing threats with the Sassanid Empire in the east and various German tribes in the west. Severus’s attempts to bribe the latter were met with indignation by his soldiers who engineered his assassination.

This had been a culmination of a gradual breakdown in military discipline, at a time when Rome needed a unified military to face its external threats.

READ MORE: Alexander Severus

The Crisis of the Third Century (235 AD – 284 AD)

After the death of Severus Alexander, the Roman Empire fell into a chaotic period of political instability, recurrent rebellions, and barbarian invasions. On a number of occasions the empire came very close to complete collapse and was perhaps saved by it actually splitting up into three different entities – with the Palmyrene Empire and Gallic Empire emerging in the east and west, respectively.

Many of the “emperors” listed above had very short reigns, or can barely be called emperors at all because of their lack of legitimation. Nonetheless, they were acclaimed emperors by themselves, their army, the praetorian guard, or the senate. For many, we lack much credible information.

Maximinus I Thrax (235 AD – 238 AD)

Maximinus Thrax was the first individual to be named emperor after the murder of Severus Alexander – by his troops in Germania. He immediately executed many of those who were close to his predecessor, but then became occupied fighting various barbarian tribes along the northern frontiers.

He was soon opposed by Gordian I and his son Gordian II, who the senate had sided with, either out of fear or political preference. Maximinus outlived the Gordian threat but was eventually assassinated by his soldiers whilst waging war against the next opposing emperors the senate had promoted – Pupienus, Balbinus, and Gordian III.

READ MORE: Maximinus

Gordian I (238 AD) and Gordian II (238 AD)

The Gordian’s came to power through an African revolt, during which he was proconsul of Africa Proconsularis. After the people effectively forced him into power he named his son as co-heir and obtained the favor of the senate through a commission.

It seems as though the senate had become displeased and disgruntled by Maximinus’s oppressive rule. However, Maximinus had the support of Capelianus, governor of neighboring Numidia, who marched against the Gordians. He killed the younger Gordian in battle, after which the elder killed himself in defeat and dismay.

READ MORE: Gordian I

READ MORE: Gordian II

Pupienus (238 AD) and Balbinus (238 AD)

After the defeat of the Gordians, the senate became afraid of Maximinus’s likely retribution. In anticipation of this, they promoted two of their own as joint emperors – Pupienus and Balbinus. The people however did not approve of this and were only assuaged when Gordian III (Gordian I’s grandson) came to power.

Pupienus marched towards northern Italy to conduct military affairs against the approaching Maxminus, whilst Balbinus and Gordian remained in Rome. Maximinus was murdered by his own mutinous troops, after which Pupienus returned to the capital, which had been badly managed by Balbinus.

By the time he got back, the city was in uproar and rioting. It was not long before both Pupienus and Balbinus were murdered by the praetorian guard, leaving Gordian III in sole command.

READ MORE: Pupienus

READ MORE: Balbinus

Gordian III (238 AD – 244 AD)

Because of Gordian’s young age (13 at his accession), the empire was initially ruled by aristocratic families in the senate. In 240 AD there was a revolt in Africa that was quickly put down, after which the praetorian prefect and father-in-law of Gordian III, Timesitheus rose to prominence.

He became the de facto ruler of the empire and went east with Gordian III to face the serious threat of the Sassanid Empire under Shapur I. They initially pushed back the enemy, until both Timesitheus and Gordian III died (perhaps in battle) in 243 AD and 244 AD, respectively.

READ MORE: Gordian III

Philip I “The Arab” (244 AD – 249 AD) and Philip II (247 AD – 249 AD)

Philip “The Arab” was a praetorian prefect under Gordian III and rose to power after the latter was killed in the East. He named his son Philip II as his co-heir, maintained good relations with the senate, and made peace with the Sassanid Empire early on in his reign.

He was often preoccupied with wars along the north-western frontier but managed to celebrate Rome’s one-thousandth birthday in 247 AD. Yet issues along the frontier culminated in recurrent invasions and the rebellion of Decius, which led to Philip’s defeat and eventual demise, along with his son.

READ MORE: Philip the Arab

Decius (249 AD – 251 AD) and Herrenius Etruscus (251 AD)

Decius had rebelled against the Philips and come out as emperor, naming his own son Herrenius as co-ruler. Like their predecessors, however, they were immediately beset by issues on the northern frontiers, of continuous barbarian invasions.

Aside from some political reforms, Decius is well known for his persecution of Christians, setting the precedent for some later emperors. He was not allowed to properly pursue this however, as he was killed with his son in battle, against the Goths (less than two years into their reigns).

READ MORE: Decius

Trebonianus Gallus (251 AD – 253 AD), Hostilian (251 AD), and Volusianus (251 – 253 AD)

With Decius and Herrenius killed in battle, one of their generals – Trebonianus Gallus – claimed the throne, and unsurprisingly named his son (Volusianus) as co-ruler. However, his predecessor’s other son, named Hostilian, was still alive in Rome and was supported by the senate.

As such, Trebonianus made Hostilian co-emperor as well, although the latter died soon after in uncertain circumstances. During 251-253 AD, the empire was invaded and laid waste to by both the Sassanids and the Goths, whilst a rebellion led by Aemilian led to the assassination of the two remaining emperors.

READ MORE: Trebonianius Gallus

Aemilian (253 AD) and Sibannacus* (253 AD)

Aemilian, who was previously a commander in the province of Moesia had rebelled against Gallus and Volusianus. After the murder of the latter emperors, Aemilian became emperor and promoted his earlier defeat of the Goths which had given him the confidence to rebel in the first place.

He did not last long as emperor as another claimant – Valerian – marched towards Rome with a larger army, prompting Aemilian’s troops to mutiny and kill him in September. There is then a theory* that an otherwise unknown emperor (save a pair of coins) reigned briefly in Rome called Sibannacus. Nothing more is known of him, however, and it seems he was soon replaced by Valerian.

READ MORE: Aemilian

Valerian (253 AD – 260 AD), Gallienus (253 AD – 268 AD) and Saloninus (260 AD)

Unlike many of the emperors who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, Valerian was of senatorial stock. He ruled jointly with his son Gallienus until his capture by the Sassanid ruler Shapur I, after which he suffered miserable treatment and torture until his death.

Both he and his son were troubled by invasions and revolts across the northern and eastern frontiers so the empire’s defense was effectively split between them. Whilst Valerian suffered his defeat and death at the hands of Shapur, Gallienus was later killed by one of his own commanders.

During Gallienus’s reign, he made his son Saloninus junior emperor, though he did not last long in this position and was soon killed by the Gallic Emperor that had risen up in opposition to Rome.

READ MORE: Valerian the Elder

READ MORE: Gallienus

Claudius II (268 AD – 270 AD) and Quintillus (270 AD)

Claudius II was given the name “Gothicus” for his relative success fighting the ever-present Goths who were invading Asia Minor and the Balkans. He was also popular with the senate and was of barbarian stock, having risen up the ranks in the Roman army before becoming emperor.

During his reign, he also defeated the Alemanni and won a number of victories against the breakaway Gallic Empire in the West that had rebelled against Rome. However, he died in 270 AD from the plague, after which his son Quintillus was named emperor by the senate.

This however was opposed by the bulk of the Roman army that had fought with Claudius, as a prominent commander called Aurelian was preferred. This, and the relative lack of experience of Quintillus led to the latter’s death at the hands of his troops.

READ MORE: Claudius II Gothicus

READ MORE: Quintillus

Aurelian (270 AD – 273 AD)

In a similar mold to his predecessor and former commander/emperor, Aurelian was one of the more effective military emperors that ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century. For many historians, he was pivotal to the Empire’s (albeit temporary) recovery and the end of the aforementioned Crisis.

This is because he managed to defeat successive barbarian threats, as well as defeating both the breakaway empires that turned away from Rome – The Palmyrene Empire and The Gallic Empire. After bringing about this remarkable feat, he was assassinated in unclear circumstances, to the shock and dismay of the whole empire.

However, he had managed to bring back a level of stability that successive emperors could build upon, propelling them out of the Crisis of the Third Century.

READ MORE: Emperor Aurelian: “Restorer of the World”

Tacitus (275 AD – 276 AD) and Florianus (276 AD)

Tacitus was reportedly selected as emperor by the Senate, very unusually for the time. However, this narrative is quite strongly disputed by modern historians, who also dispute the claim that there was a 6-month interregnum between the rule of Aurelian and Tacitus.

Nonetheless, Tacitus is depicted as being on good terms with the Senate, returning to them many of their old prerogatives and powers (although these did not last long). Like almost all of his predecessors, Tacitus had to deal with many barbarian threats across the frontiers. Returning from one campaign he fell ill and died, after which his half-brother Florianus rose to power.

Florianus was soon opposed by the next emperor Probus, who marched against Florianus and wore down his opponent’s army very effectively. This led to the murder of Florianus at the hands of his disaffected troops.

READ MORE: Tacitus

READ MORE: Florian

Probus (276 AD – 282 AD)

Building on the success of Aurelian, Probus was the next emperor to help push the empire out of its 3rd-century crisis. After gaining recognition from the senate at the successful end of his rebellion, Probus defeated the Goths, Alemanni, Franks, Vandals, and more – sometimes going beyond the frontiers of the empire to decisively defeat different tribes.

He also put down three different usurpers and fostered strict discipline throughout the army and the empire’s administration, again, building on the spirit of Aurelian. Nonetheless, this extraordinary string of successes did not prevent him from being assassinated, reportedly through the schemes of his praetorian prefect and successor Carus.

READ MORE: Probus

Carus (282 AD – 283 AD), Carinus (283 AD – 285 AD), and Numerian (283 AD – 284)

Following the trend of previous emperors, Carus came to power and proved to be a successful emperor militarily, even though he only lived for a short amount of time. He was successful in repelling Sarmatian and Germanic raids but was killed whilst campaigning in the east against the Sassanids.

It is reported that he was struck by lightning, though this may just be a fanciful myth. His sons Numerian and Carinus succeeded him and whilst the latter soon became known for his excess and debauchery in the capital, the former son was assassinated in his camp in the east.

After this, Diocletian, a commander of the bodyguards was acclaimed emperor, after which Carinus reluctantly went east to face him. He was defeated at the Battle of the Margus River and died soon after, leaving Diocletian in sole command.

READ MORE: Carus

READ MORE: Carinus

READ MORE: Numerian

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (284 AD – 324 AD)

The ruler to bring the tumultuous Crisis of the Third Century to its end, was none other than Diocletian who had risen up the ranks in the army, having been born in a family of low status in the province of Dalmatia.

Diocletian brought more enduring stability to the empire through his implementation of the “Tetrarchy” (“rule of four”), wherein the empire was administratively and militarily split into four, with a different emperor ruling over his respective portion. Within this system, there were two senior emperors, called Augusti, and two junior ones called Caesari.

With this system, each emperor could focus more carefully on his respective region and its concomitant frontiers. Invasions and rebellions could therefore be put down much more swiftly and the affairs of state more carefully managed from each respective capital – Nicomedia, Sirmium, Mediolanum, and Augusta Treverorum.

This system lasted, in one or another, until Constantine the Great dethroned his opposing emperors and re-established sole rulership for himself.

Diocletian (284 AD – 305 AD) and Maximian (286 AD – 305 AD)

Having established himself as emperor, Diocletian first campaigned against the Sarmatians and Carpi, during which he first split the empire with Maximian, who he elevated to co-emperor in the west (whilst Diocletian controlled the east).

Apart from his constant campaigning and construction projects, Diocletian also massively expanded the state bureaucracy. Moreover, he carried out extensive tax and pricing reforms, as well as large-scale persecution of Christians across the empire, who he saw as a pernicious influence within it.

As with Diocletian, Maximian spent much of his time campaigning along the frontiers. He also had to suppress rebellions in Gaul but failed to suppress a full-scale revolt led by Carausius who took over Britain and north-western Gaul in 286 AD. Subsequently, he delegated the confrontation of this threat to his junior emperor Constantius.

Constantius was successful in defeating this latest breakaway state, after which Maximian confronted pirates and Berber invasions in the south before retiring to Italy in 305 AD (although not for good). In the same year, Diocletian also abdicated and settled along the Dalmatian coast, building himself an opulent palace to live out the rest of his days.

READ MORE: Diocletian

READ MORE: Maximian

Constantius I (305 AD – 306 AD) and Galerius (305 AD – 311 AD)

Constantius and Galerius were the junior emperors of Maximian and Diocletian, respectively, who both rose to full Augusti when their predecessors retired in 305 AD. Galerius seemed intent on securing the empire’s continued stability by appointing two new junior emperors – Maximinus II and Severus II.

His co-emperor Constantius did not live for long, and whilst campaigning against the Picts in Northern Britain, he died. Upon his death, there was a splintering of the Tetrarchy and its overall legitimacy and durability, as a number of claimants came to the fore. Severus, Maxentius, and Constantine were all acclaimed emperors around this time, to the ire of Galerius in the east, who had just expected Severus to become emperor.

READ MORE: Constantius Chlorus

READ MORE: Galerius

Severus II (306 AD – 307 AD) and Maxentius (306 AD – 312 AD)

Maxentius was the son of Maximian, who had previously been co-emperor with Diocletian and was persuaded to retire in 305 AD. Clearly unhappy about doing so, he elevated his son to the position of the emperor against the wishes of Galerius who had promoted Severus to that position instead.

Galerius ordered Severus to march against Maxentius and his father at Rome, but the former was betrayed by his own soldiers, captured, and executed. Maximian was soon after elevated to co-emperor with his son.

Subsequently, Galerius marched into Italy attempting to force the father and son emperors into a battle, though they resisted. Finding his efforts fruitless he withdrew and called together his old colleague Diocletian to try and resolve the issues now pervading the administration of the empire.

As discussed below, these failed, and Maximian foolishly tried to overthrow his son and was in turn murdered in exile with Constantine.

READ MORE: Severus II

READ MORE: Maxentius

The End of the Tetrarchy (Domitian Alexander)

Galerius had called together an imperial meeting in 208 AD, in order to resolve the issue of legitimacy that now plagued the empire. In this meeting, it was decided that Galerius would rule in the east with Maximinus II as his junior emperor. Licinius would then rule in the west with Constantine as his respective junior; Maximian and Maxentius were both declared illegitimate and usurpers.

However, this decision quickly broke down, not only with Maximinus II rejecting his junior role but through the acclamations of Maximian and Maxentius in Italy and Domitius Alexander in Africa. There now were seven nominal emperors in the Roman Empire and with Galerius’s death in 311 AD, any formal structure linked to the Tetrarchy fell apart and a civil war between the remaining emperors broke out.

Before this Maximian had tried to overthrow his son, but misjudged the sentiment of his soldiers, fleeing to Constantine I in the aftermath, where he was murdered in 310 AD. Not long after Maxentius sent an army to confront Domitian Alexander who had risen up as de facto emperor in Africa. The latter was subsequently defeated and killed.

Bringing back stability required the strong and decisive hand of Constantine the Great to dissolve the failed experiment of the Tetrarchy and establish himself as sole ruler again.

Constantine and the Civil Wars (308 AD – 324 AD)

From 310 AD onwards Constantine went about outmaneuvering and defeating his rivals, first allying himself with Licinius and confronting Maxentius. The latter was defeated and killed at the battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD. It was not long before Maximinus, who had secretly been allied with Maxentius, was defeated by Licinius at the Battle of Tzirallum, dying soon after.

This left Constantine and Licinius in charge of the empire, with Licinius in the East and Constantine in the West. This peace and state of affairs did not last for too long and broke out into a number of civil wars – the first coming as early as 314 AD. Constantine was successful in brokering a truce after defeating Licinius at the Battle of Cibalae.

It was not long before another war broke out, as Licinius propped up Valerius Valens as a rival emperor to Constantine. This also ended in failure at the Battle of Mardia and the execution of Valerius Valens.

The uneasy peace that followed lasted until antagonisms led to a full-scale war in 323 AD. Constantine, who by this time now championed the Christian faith, defeated Licinius at the Battle of Chrysopolis, shortly after which he was captured and hung. Before his defeat, Licinius had tried in vain to prop up Martinian as another opposing emperor to Constantine. He too was executed by Constantine.

READ MORE: Magnus Maximus

READ MORE: Licinius

The Constantine/Neo-Flavian Dynasty (306 AD – 364 AD)

After bringing both the Tetrarchy and the civil wars that followed to an end, Constantine established his own dynasty, initially centering power on himself exclusively, without co-emperors.

He also propelled the Christian religion to the center of power throughout the empire, which had profound effects on subsequent history globally. Whilst Julian the Apostate stood out amongst Constantine’s successors for disavowing the Christian religion, all the other emperors mostly followed in the footsteps of Constantine in this religious regard.

Whilst political stability was restored under Constantine, his sons soon broke out into civil war and probably doomed the success of the dynasty. Invasions continued to happen and with the empire divided and at odds with itself, it became increasingly harder to withstand the immense pressures that were growing.

Constantine the Great (306 AD – 337 AD)

Having risen up to be the sole emperor experiencing a lot of military action, as well as political disarray, Constantine was instrumental in reforming both the administration of the state and the army itself.

He reformed the latter institution by developing new mobile units that could respond more quickly to barbarian invasions. Economically, he also reformed the coinage and introduced the solid gold Solidus, which stayed in circulation for another thousand years.

As has already been mentioned, he was also instrumental in promoting the Christian faith, as he funded the construction of churches throughout the empire, settled religious disputes, and gave many privileges and powers to regional as well as local clergy.

He also moved the imperial palace and administrative apparatus to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople (this arrangement was to last for another thousand years and remained the capital of the later Byzantine Empire). He died near this new imperial capital, famously being baptized before his death.

READ MORE: Constantine

Constantine II (337 AD – 340 AD), Constans I (337 AD – 350 AD), and Constantius II (337 AD – 361 AD)

After Constantine’s death, the empire was split between three of his sons – Constans, Constantine II, and Constantius II, who subsequently had much of the extended family executed (so as to not get in their way). Constans was given Italy, Illyricum, and Africa, Constantine II received Gaul, Britannia, Mauretania, and Hispania, and Constantius II took the remaining provinces in the east.

This violent start to their joint rule set a precedent for the empire’s future administration. Whilst Constantius remained preoccupied with conflict in the east – mostly with the Sassanid ruler Shapur II – Constans I and Constantine II began to antagonize each other in the West.

This led to Constantine II’s invasion of Italy in 340 AD, which resulted in his defeat and death at the Battle of Aquileia. Left in charge of the western half of the empire, Constans continued to rule and repelled barbarian invasions along the Rhine River frontier. His conduct made him unpopular, however, and in 350 AD, he was killed and overthrown by Magnentius.

READ MORE: Constantine II

READ MORE: Constans

READ MORE: Constantius II

Magnentius (350 AD – 353 AD), Nepotianus (350 AD), and Vetranio (350 AD)

On the death of Constans I in the west, a number of individuals rose up to claim their place as emperor. Both Nepotianus and Vetranio did not last the year however, whilst Magnentius managed to secure his rule over the western half of the empire, with Constantius II still ruling over the east.

Constantius who had been busy forwarding the policies of his father, Constantine the Great, knew he eventually had to confront the usurper Magnentius. In 353 AD the decisive battle came at Mons Seleucus where Magnentius was badly defeated, prompting his subsequent suicide.

Constantius continued to rule past the brief reigns of these usurpers but eventually died during the rebellion of the next usurper Julian.

READ MORE: Magnentius

Julian “The Apostate” (360 AD – 363 AD)

Julian was a nephew of Constantine the Great and served under Constantius II as an administrator of Gaul, with marked success. In 360 AD he was acclaimed emperor by his troops in Gaul, prompting Constantius to confront him – he died however before he got the chance.

Julian was subsequently established as the sole ruler and became famous for trying to reverse the Christianization that his predecessors had implemented. He also embarked upon a large campaign against the Sassanid Empire which initially proved successful. However, he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Samarra in 363 AD, dying soon after.

READ MORE: Julian the Apostate

Jovian (363 AD – 364 AD)

Jovian had been part of the imperial bodyguard of Julian before becoming emperor. His reign was very short and was punctuated by a humiliating peace treaty he signed with the Sassanid Empire. He also made initial steps to return Christianity to the fore, through a series of edicts and policies.

After putting down a riot in Antioch, which infamously involved burning down the Library of Antioch, he was found dead in his tent on the way to Constantinople. After his death, a new dynasty was founded by Valentinian the Great.

READ MORE: Jovian

The Valentinian (364 AD – 394 AD) and Theodosian (379 AD – 457 AD) Dynasties

After the death of Jovian, at a meeting of civil and military magistrates, Valentinian was eventually decided upon as the next emperor. Along with his brother Valens, he established a dynasty that ruled for nearly a hundred years, along with the dynasty of Theodosius, who actually married into the Valentinian line.

Together the dual dynasties maintained relative stability over the empire and oversaw its permanent split into the Western and Eastern (later Byzantine) Empires. The Theodosian side outlived the Valentinian side and ruled mostly in the east, whereas the latter ruled mostly over the western half of the empire.

Even though they collectively represented a surprisingly stable period of the Roman Empire in Late Antiquity, the empire continued to be beset by recurrent invasions and endemic issues. After the demise of both dynasties, it was not long before the empire fell in the west.

Valentinian I (364 AD – 375 AD), Valens (364 AD – 378 AD), and Procopius (365 AD – 366 AD)

After being named emperor, Valentinian noticed the precariousness of his situation and consequently acclaimed his brother Valens as co-emperor. Valens was to rule over the east, whilst Valentinian focused on the west, naming his son Gratian as co-emperor with him there (in 367 AD).

Described in quite unfavorable terms, Valentinian was depicted as a humble and militaristic man, who spent much of his reign campaigning against different German threats. He also was forced to address “The Great Conspiracy” – a rebellion that arose in Britain coordinated by a conglomeration of different tribes.

Whilst arguing with an envoy of the German Quadi, Valentinian had a fatal stroke in 375 AD, leaving the western half of the empire to his son, Gratian.

The reign of Valens in the east was characterized in much the same way as Valentinian’s, constantly being embroiled in conflicts and skirmishes along the eastern frontiers. He was depicted as a capable administrator, but a poor and indecisive military man; no wonder then, he met his death against the Goths at The Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD.

He had been opposed by Procopius, who led a rebellion against Valens in 365 AD, declaring himself emperor in the process. This however did not last long before the usurper was killed in 366 AD.

READ MORE: Valentinian

READ MORE: Valens

Gratian (375 AD – 383 AD), Theodosius the Great (379 AD – 395 AD), Magnus Maximus (383 AD – 388 AD), Valentinian II (388 AD – 392 AD), and Eugenius (392 AD – 394 AD)

Gratian had accompanied his father Valentinian I on many of his military campaigns and was therefore well prepared to face the growing barbarian threat across the Rhine and Danube frontiers when he became emperor. However, to help him with this endeavor, he named his brother Valentinian II as the junior emperor of Pannonia, to watch over the Danube specifically.

After the death of Valens in the east, Gratian promoted Theodosius who had married his sister to the position of co-emperor in the east, in what turned out to be a wise decision. Theodosius managed to hold onto power for some time in the east, signing peace treaties with the Sassanid empire and holding back a number of major invasions.

He was also remembered as a capable administrator and champion of the Christian faith. When Gratian and his brother Valentinian II died in the east, Theodosius marched west to first confront Magnus Maximus and later Eugenius, defeating them and uniting the empire for the last time under one emperor.

Magnus Maximus led a successful revolt in Britain in 383 AD, making himself emperor there. When Gratian confronted him in Gaul, he was roundly defeated and killed soon after. The usurper was then recognized for a time by Valentinian II and Theodosius before being defeated and killed by the latter in 388 AD.

Because of Theodosius’s strict enforcement of Christian doctrine (and concomitant enforcement against the pagan practice) across the empire, discontent grew, especially in the west. This was capitalized upon by Eugenius who rose up with the help of the senate in Rome to become emperor in the west in 392 AD.

However, his rule was not recognized by Theodosius, who marched west again and defeated the usurper at the Battle of Frigidus in 394 AD. This left Theodosius as the sole and undisputed ruler of the Roman world, until his death a year later in 395 AD.

READ MORE: Gratian

READ MORE: Theodosius

READ MORE: Magnus Maximus

READ MORE: Valentinian II

Arcadius (395 AD – 408 AD) and Honorius (395 AD – 423 AD)

As sons of the relatively successful Theodosius, both Honorius and Arcadius were very underwhelming emperors, dominated by their ministers. The empire also experienced recurrent incursions into its territory, especially by a marauding band of Visigoths under Alaric I.

Having been manipulated throughout his reign by his court ministers and wife, as well as the guardian of his brother Stilicho, Arcadius passed away in uncertain circumstances in 408 AD. Honorius however, was to suffer greater ignominy, as in 410 AD the Goths sacked the city of Rome – the first time it had fallen since 390 BC.

Following this, Honorius continued to rule as an ineffective emperor away from Rome in Ravenna, as he struggled to deal with the usurper emperor Constantine III. He died in 423 AD having outlived Constantine, but leaving the empire in the west in disarray.

READ MORE: Arcadius

READ MORE: Honorius

Constantine III (407 AD – 411 AD) and Priscus Attalus (409 AD – 410 AD)

Both Constantine and Priscus Attalus were usurping emperors who capitalized on the chaos of Honorius’s reign in the west, around the time of Rome’s sack in 410 AD. Whilst Priscus – who was propped up by the senate and Alaric the Goth – did not last long as emperor, Constantine managed to temporarily hold onto large portions of Britain, Gaul, and Hispania.

Eventually, however, he was defeated by Honorius’s armies and subsequently executed in 411 AD.

READ MORE: Constantine III

Theodosius II (408 AD – 450 AD), the Usurpers in the West (Constantius III (421 AD) and Johannes (423 AD – 425 AD)), and Valentinian III (425 AD – 455 AD)

Whilst Theodosius II followed in his father’s footsteps upon the latter’s death, things in the west did not proceed as smoothly. Honorius had made his general Constantius his co-emperor in 421 AD, however, he died in the same year.

After Honorius’s own death, a usurper named Johannes was acclaimed emperor before Theodosius II could decide on a successor. Eventually, he selected Valentinian III in 425 AD, who marched westwards and defeated Johannes that same year.

The subsequent joint reigns of Theodosius II and Valentinian III mark the last moment of political continuity across the empire before the empire began to disintegrate in the west. Much of this cataclysm in fact occurred during Valentinian’s reign, with the emperor portrayed as incompetent and indulgent, more focused on pleasure than patrolling the empire.

During his reign, much of the western part of the empire fell out of Roman control, at the hands of various invaders. He was able to repel the invasion of Attila the Hun but failed to stem the flow of invasions elsewhere.

Theodosius for his part was more successful and managed to repel a number of different invasions as well as develop legal reforms and the fortification of his capital at Constantinople. He died from a riding accident in 450 AD, whilst Valentinian was assassinated in 455 AD, with much of the empire in disarray.

READ MORE: Theodosius II

READ MORE: Valentinian III

Marcian (450 AD – 457 AD)

After the death of Theodosius II in the east, the soldier and official Marcian was nominated as emperor and acclaimed in 450 AD. He quickly reversed many of the treaties his predecessor has made with Attila and his armies of Huns. He also defeated them in their own heartland in 452 AD.

After Attila’s death in 453 AD, Marcian settled many Germanic tribes in Roman lands in the hope of bolstering the empire’s defenses. He also went about revitalizing the economy of the east and reforming its laws, as well as weighing in on some important religious debates.

In 457 AD Marcian died (reportedly of gangrene), having refused to acknowledge any emperor in the west since the death of Valentinian III in 455 AD.

READ MORE: Marcian

The Last Emperors of the West (455 AD – 476 AD)

After the death of Marcian in the east, Leo was propped up by members of the army who believed he would prove to be a puppet ruler, easy to manipulate. However, Leo proved adept at the ruling and stabilized the situation in the east, whilst coming close to salvaging something out of the chaos that the west was embroiled in.

Alas, he was ultimately unsuccessful in this endeavor, as the Roman Empire in the west fell two years after his death. Before this, it had seen a catalog of different emperors who all failed to stabilize the frontiers and recover the vast tracts of land that had fallen out of the empire’s grip during the reign of Valentinian III.

Many of them were controlled and manipulated by the powerful magister militruml of Germanic descent, named Ricimer. During this fateful period, the emperors in the west had effectively lost control of all regions except for Italy, and soon that was to fall as well, to German invaders.

READ MORE: Leo the Great

Petronius Maximus (455 AD)

Petronius had been behind the murder of Valentinian III and his prominent military commander Aëtius. He had subsequently taken the throne by bribing senators and palace officials. He married his predecessor’s widow and refused the betrothal of their daughter to a Vandal prince.

This infuriated the Vandal prince who subsequently sent an army to besiege Rome. Maximus fled, being killed in the process. The city was sacked for the next two weeks, with the Vandals destroying a considerable amount of infrastructure.

READ MORE: Petronius Maximus

Avitus (455 AD – 465 AD)

After the ignominious death of Petronius Maximus, his head general Avitus was proclaimed emperor by the Visigoths, who had intermittently aided or opposed Rome. His reign failed to receive legitimization from the east, just as had occurred for his predecessor.

Moreover, whilst he won a couple of victories against the Vandals in Southern Italy, he failed to obtain real favor within the senate. His ambiguous relationship with the Visigoths is blamed, as he allowed them to capture portions of Hispania ostensibly for Rome, but really for their own interests. He was deposed by a rebel faction of senators in 465 AD.

READ MORE: Avitus

Majorian (457 AD – 461 AD)

Majorian was proclaimed emperor by his troops after successfully repulsing an Alemannic army in Northern Italy. He was accepted by his counterpart in the east Leo I, granting him a level of legitimacy that his last two predecessors had lacked.

He was also the last emperor in the west who tried to properly address its precipitous fall, by taking back the territory it had recently lost and by reforming its imperial administration. He was initially successful in this effort, having defeated the Vandals, Visigoths, and Burgundians and taken back large portions of Gaul and Hispania.

However, he was eventually betrayed by commander Ricimer, who was a very influential and pernicious force in the dying days of the Western Roman Empire. In 461 AD Ricimer captured him, deposed, and decapitated him.

READ MORE: Majorian

Libius Severus (461 AD – 465 AD)

Libius was propped up by the nefarious Ricimer who had murdered his predecessor. It is believed that Ricimer held much of the power during his reign, which was itself marked by calamity and regression. All of the territory recaptured by Majorian was lost, and both the Vandals and Alans raided Italy, which was the only region still nominally under Roman control.

In 465 AD he died, under obscure circumstances.

READ MORE: Libius Severus

Anthemius (467 AD – 472 AD) and Olybrius (472 AD)

As the Vandals were laying waste to coastlands throughout the Mediterranean, Leo I, Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, appointed Anthemius to the throne in the west. The new emperor was a distant relation of Julian “the Apostate” and was determined to break the stranglehold the Germanic general Ricimer had over the western half of the empire.

He also worked with his counterpart Leo to try to reverse the territorial losses suffered in the west. They were both unsuccessful in this, first in North Africa and then in Gaul. Antagonisms between Anthemius and Ricimer also came to a head in 472 AD, leading to Anthemius’ deposition and decapitation.

Ricimer subsequently placed Olybrius on the throne, shortly before the former’s death. Olybrius did not rule for long and was most probably controlled by Ricimer’s cousin Gundobad, just as Olybrius’s predecessors had been controlled by Ricimer. The new puppet emperor died in late 472 AD, reportedly of dropsy.

READ MORE: Anthemius

READ MORE: Olybrius

Glycerius (473 AD – 474 AD) and Julius Nepos (474 AD – 475 AD)

Glycerius was propped up by Germanic general Gundobad after the death of Olybrius. Whilst his armies had managed to repel an invasion of barbarians in Northern Italy, he was opposed by Leo I in the east, who sent Julius Nepos with an army to depose him in 474 AD.

Having been abandoned by Gundobad, he abdicated in 474 AD, allowing Nepos to take the throne. Nepos’s reign in Ravenna (the capital of the empire in the west) was short-lived however, as he was opposed by the latest magister militum Orestes, who forced Nepos into exile in 475 AD.

READ MORE: Glycerius

READ MORE: Julius Nepos

Romulus Augustus (475 AD – 476 AD)

Orestes placed his young son Romulus Augustus on the throne of the Roman Empire but effectively ruled in his stead. Before long however, he was defeated by the barbarian general Odoacer, who deposed Romulus Augustus and failed to name a successor, thus bringing to a close the Roman Empire in the west (although Julius Nepos was still recognized by the eastern empire until his death in exile in 480 AD).

Whilst the writing had been on the wall for some time in the west, the last series of emperors had been especially hampered by the nefarious schemes of their magister militums, particularly Ricimer.

Although the empire lived on for centuries in the east, morphing into the Byzantine Empire, the fall of the Roman Empire in the west was complete, and its emperors were no more.

READ MORE: Romulus Augustus