Roman women were the silent wives, the mothers, the daughters, and the priestesses in the background. Even when they were queens, their voices came after the men around them. So what were the Roman women like? What kind of lives did women live in the Roman Empire? What kind of laws and policies did ancient Rome have that related to women?

Table of Contents

Who Were Roman Women?

Roman women played various roles in the ancient Roman Empire. Other than the dutiful daughter, wife, and mother, they also had careers such as shopkeeping or being a midwife or priestess. Roman goddesses were immensely respected, but Roman women not so much and they didn’t have a voice in public life. Even their history comes to us from men, other than the writings of a few female philosophers and writers. Whether they were free women or slaves, their lives and narratives were controlled by the men around them.

Place in the Family

In Roman society, as in many ancient civilizations, the value of a woman was mostly in relation to her father or husband. It was her duty to marry well and to take care of the household and her children after marriage. Roman girls were married off by their teens. After her marriage, her devotion to her husband was the stick by which she was measured.

Pliny the Younger wrote most affectionately of his young bride Calpurnia, who at 15 was some 25 years younger than him. Her attempt to memorize his writings apparently endeared her to him. Other writers, such as Ovid and Cicero, were not as kind to Roman women. They wrote scathingly of their primitive nature, their high sex drives, and their lack of sound judgment, things Romans believed were fact. Most Roman men especially looked upon a mother-in-law with loathing.

A Roman woman was primarily brought up indoors. The house, not public life, was her domain. The skills they were allowed to acquire revolved around running a household and raising children. The model Roman women were those who spun their own cloth, oversaw the domestic affairs of their family, and provided their husbands with many children, food, and a smoothly run household. They also had to be suitably modest. The Roman household was headed by the ‘materfamilias,’ which meant ‘mother of the family.’

Women in ancient Rome did not even have a right to their own, unique names. Most of the time, their names were a variation of their fathers’ names. Thus, a man named Julius would have a daughter named Julia. He might even have multiple daughters named Julia: Julia Major, Julia Minor, and Julia Tertia.

Wealthy Roman Women

Wealthy women and poorer women lived different lives in ancient Rome. While both were brought up primarily indoors, the home continued to be the domain of wealthy women into their adult lives. A poor woman or a slave, by contrast, would have to go out to work to support their families. Poor women could work as shopkeepers, midwives, wet nurses, servants, scribes, and courtesans.

A wealthy Roman woman had a much easier life. She did not need to do much household work herself, since she had servants to do it for her. She only needed to instruct the servants on their chores and make sure everything was being run smoothly. Wealthy women were sometimes taught to read and write and do accounts. Once they had children, the children would be turned over to the care of wet nurses and slaves.

Wealthy Roman women often spent their time planning parties and networking with their contemporaries. The women from the wealthiest and most influential families might have had some influence on their husbands and sons. That was the means by which they snatched power. However, no woman could vote, whether rich or poor or slave.

Religion Afforded Freedom

Religion often served as an escape in ancient Rome. Two of the most important Roman deities were women – Juno and Minerva. Being a priestess was considered a position of great honor and one where the woman in question could not be married off to a man much older than her. Even a woman from a wealthy and influential family could become a priestess.

Some of the most important people in ancient Rome were the Vestal Virgins – the priestesses of the goddess Vesta. These were six young women who had sacred duties like preserving the fire in the temple of Vesta. They also safeguarded the wills of important Roman citizens like Julius Caesar. This gave them immense power and prestige and they could use it to negotiate with powerful men if they wished to. The Vestal Virgins did use their power when they stepped in to save young Julius Caesar from the dictator Sulla.

To become Vestal Virgin, Roman women needed to be appointed before puberty and remain chaste for 30 years. Girls had to be free of any physical or mental disabilities, had to be the daughter of a free-born resident of Rome, and had to have two living parents to enter the order. They were elected into positions as Vestal Virgins. They could not marry or have children.

What Was the Roman Ideal of Female Beauty?

When we come to ancient Roman beauty standards, it is a slippery slope. Women presided over the household and were meant to be the face of the home. Their appearance reflected on their husbands, thus it would not do for them to be shabbily dressed and made up. But being overly dressed up and trying to look more youthful than one was would lead to critique. However, all of these accounts come to us from men, so it isn’t actually clear what the women’s ideas on beauty were.

From the statues and art that we have, it seems evident that women in ancient Rome paid attention to their appearance. Wealthy Roman women had hairdressers to style their hair in extremely elaborate fashion. Natural cosmetics and beauty products like rose petals and honey were used to take care of the skin. Clothes were spun and sewn at home and reflected one’s status in society.

What Rights Did Women Have Under Early Roman Law?

When we speak of ancient Rome, we refer to both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. Laws and political decrees differed greatly from one to the other. From the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus, the change in the status of women was significant. In some ways, their legal status became worse, since the laws punishing adulterous women were toughened. But in other ways, the status of Roman women improved, since the Julian laws allowed a woman who had had at least three children to be exempt from the guardianship of a man. This allowed them to emerge from the shadows a little bit. The wife of Augustus, Livia, was one of the most powerful Roman women to ever live.

Education

In Roman times, daughters were usually taught the skills of the household. Rich Roman women might learn some reading and writing. But there were also some exceptions. The Roman Republic was more permissive about women’s education than the early empire under Augustus. One Republican woman who was highly educated was Hortensia, the daughter of Cicero’s rival Hortensius. She was also a brilliant orator and made several public speeches, which was usually the province of men. All of this changed with the Roman Empire, which was much stricter with its rules.

As per the later laws, Roman girls were taught reading, writing, and mathematics. These skills would equip them to manage the expenses of the home and be an entertaining companion to their husband. Girls could not be taught more than these fundamentals because the Romans believed that would make them dangerous. The more learning a woman had, the more pretentious and sexually promiscuous she would become. Thus, Roman society became even more misogynistic under the Empire, an interesting contrast to the Roman empresses trying to grasp power within the Imperial household.

READ MORE: Who Invented Math? The History of Mathematics

Marriage and Divorce

Under Emperor Augustus, a new law stated that Roman women who were not married by the age of 20 would face legal penalties and marginalization. Girls were usually married off by the age of 14 or 15. Interestingly enough, divorce could still take place in Roman society and a woman could divorce her husband.

Divorce did not have any special legal procedures. One of the spouses could simply ask for a divorce on the grounds that they wanted one. Divorces in political marriages were especially common when one party decided that they did not need the political support of the other party anymore. Fathers could ask for their daughters to divorce their husbands and the daughter would need to return to her father’s house.

Custody of children was often given to the husband and the wife had to leave her children behind when she returned to her father’s house. In abusive cases, men often tried to keep their wives’ dowries after a divorce. They might make accusations of adultery in such a case and demand the dowry as compensation.

Politics

When it came to politics, Roman women usually had no say in public life. The only way for women to have some influence in the Roman Empire or Republic was to carve a space for themselves alongside their husbands or sons.

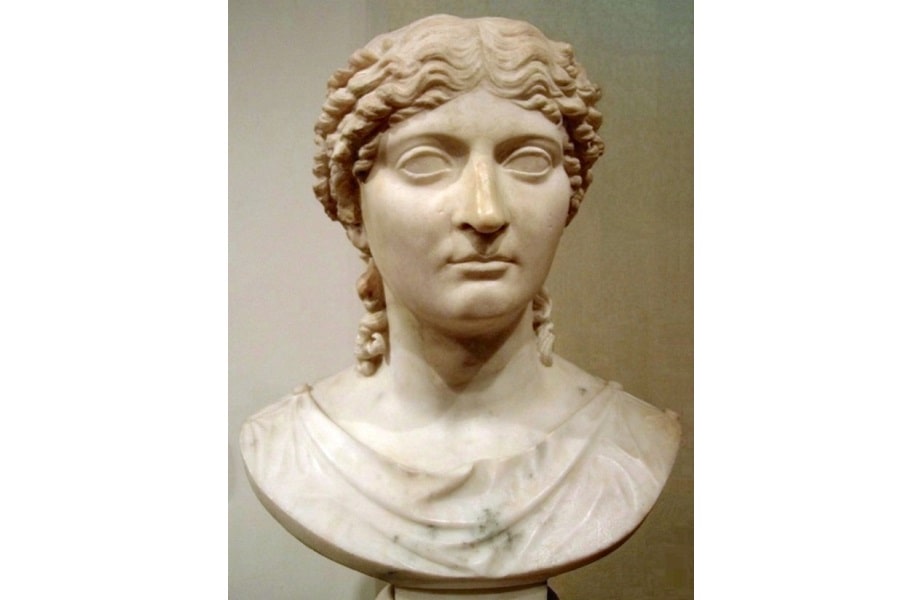

One example of this would be Cornelia, daughter of the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. Cornelia was well-educated and had a lot of military and political knowledge since her father held political office. She was widowed at a young age and emerged as a powerful and intellectual presence even during her marriage. After the death of her husband, Cornelia refused several marriage offers. One of these was from the Egyptian pharaoh, Ptolemy VIII.

Cornelia raised her three children alone. Her two sons, the Gracchi brothers, eventually embarked on a series of populist reforms. In public, Cornelia backed them. But in private, it is believed that she wrote them several letters to scold them for their actions. Both brothers were later assassinated. But Cornelia enjoyed great respect and awe for her duality of immense learning and devotion to her family.

Faustina the Younger was another figure who was greatly revered. She was married at 15 to the future emperor Marcus Aurelius and bore him 14 children. She accompanied him on his military campaigns, was cherished as the ‘mother of the camp,’ and was granted the high title of Augusta.

Did Roman Women Have Power?

Despite this, it would not be correct to say that Roman women had much of a voice in their society. Yes, some empresses and female relatives of senators may have been well respected. But they were not the norm. They were the exceptions to the rule. It is the ordinary people of society who decide the nature of that society. Studies show that Roman society was a male-dominated and extremely misogynistic society where ordinary women did not have much power.

Still, In ancient Rome, a few women had some official political power. And we should look at these women for a well-rounded study of the culture. How much influence women did have over their husbands and sons who were part of the Roman senate is an interesting question. Were they reviled for this by other powerful men? Were they seen as wise matriarchs or grasping, power-hungry tyrants? Alas, it seems the answer is the latter.

Ambitions and Backlash

In ancient Rome, most of the Roman Empresses who exercised any influence over their menfolk were hounded by rumors of poisoning and murder schemes. This is probably because the men around them were nervous about their closeness to the Roman Emperors and wished to discredit them. A woman in a position of power was to be feared.

Thus, it was better to spread rumors about people like the wife of the first Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar, Livia Drusilla. There is no evidence that Livia poisoned her husband, although she did make sure that her son Tiberius was named the Emperor after the death of Emperor Augustus. Livia was said to wield a terrifying amount of power over the aging Augustus and was supposedly responsible for the poisoning and exile of his grandsons.

Julia Agrippina was another such woman who faced great backlash. She was the mother of Nero and his staunch defender. She had married (and possibly poisoned) her way to power and had received the title of Augusta, bestowed on very few Roman Empresses. She placed young Nero on the throne and acted as his regent. She is also said to have murdered Nero’s stepbrother Brittanicus and Nero’s stepfather, Claudius, her third husband. Nero himself is said to have conspired to kill his mother, as well as his own wife Poppaea, who also exercised considerable influence over him.

Some powerful women who were not dogged by rumors of backstabbing and poisoning were Fulvia, Octavia Minor, and Helena. Fulvia was married to three extremely influential men, the third being Mark Antony. All of her husbands were supporters of Julius Caesar and had very promising political careers. Fulvia gained power and wealth through her first two husbands and used this to raise troops for Mark Antony in opposition to Octavian (who later became Emperor Augustus). Octavian won and Fulvia subsequently died of illness. After her death, the two men publicly reconciled and blamed Fulvia for their disagreements. Mark Antony was then married to Octavia Minor, Octavian’s older sister.

Octavia was something of a role model for Roman women. She was a loyal wife, intelligent, and beautiful. She helped Mark Antony and her brother reconcile their differences and took care of his children from his former marriage, even after he ran off with Cleopatra and divorced her. Octavia still tried to rally troops for Mark Antony and soothe things between the two men. On his death, she was granted full custody of all of his children, even those by Fulvia and Cleopatra. By all accounts, she welcomed them to her household very kindly.

READ MORE: How Did Cleopatra Die? Bitten by an Egyptian Cobra

Helena was the mother of Emperor Constantine. She was a lower-class woman and quite possibly Greek by birth. Yet, she had enormous influence over her son. She could convince him to pardon people who were to be executed and her conversion to Christianity was a big reason for Constantine becoming the first Christian king. Now, Helena is considered a saint and called Saint Helena by the Christians.

READ MORE: How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact