Roman baths were much more than mere bathing facilities; they were integral to ancient Roman society, serving as places of hygiene, socialization, and even healing. These magnificent structures were meticulously designed, with grand architectural features that showcased the prowess and opulence of the Roman Empire.

Table of Contents

What are Roman Baths?

Roman baths were large, multi-story buildings with impressive architectural designs, and they played a significant role in Roman society and culture, serving as places for hygiene, socialization, and healing. They could be found in nearly all Roman cities, and their design and operation were influenced by earlier Greek and Hellenistic bathing traditions.

Today, the remainings of ancient Roman baths can be found all over Europe and in some parts of North Africa. They are valuable archaeological sites and popular tourist attractions offering insights into the ancient Roman way of life.

Architecture and Design of Roman Baths

One remarkable architectural element of Roman baths was the extensive use of columns. Columns, often made of marble or granite, adorned the entrances, courtyards, and halls of the bath complexes [3]. These columns showcased different architectural orders such as Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, adding a sense of elegance and sophistication to the overall design.

Another notable architectural feature of Roman baths was the inclusion of large windows and skylights to maximize natural light. These windows, often adorned with decorative grilles, allowed sunlight to illuminate the interior spaces of the baths, creating a bright and welcoming atmosphere. The natural light not only enhanced the aesthetic appeal but also provided a sense of openness and connection with the surrounding environment. The Baths of Diocletian in Rome showcased this architectural design with its vast windows and open-air courtyards, creating a harmonious blend of indoor and outdoor spaces [6].

Roman baths were also renowned for their intricate mosaic artwork. Mosaics adorned the floors, walls, and ceilings of the bath complexes, showcasing scenes from mythology, nature, and daily life. The mosaics were created using small colored tiles called tesserae, arranged to form intricate patterns and detailed images. These stunning mosaics added a touch of luxury and artistry to the bathing experience. The House of the Faun in Pompeii, with its famous Alexander Mosaic depicting the Battle of Issus, is a remarkable example of the intricate mosaic artistry found in Roman baths [1].

The use of water features and fountains was another prominent aspect of Roman bath architecture. Water, symbolizing purity and rejuvenation, played a central role in the bathing rituals. Elaborate water systems were designed to supply the baths with an abundant and constant flow of fresh water. Fountains, often adorned with sculptures and decorative elements, created a soothing and serene ambiance. The Baths of Caracalla featured magnificent water cascades, pools, and fountains that added a sense of tranquility and beauty to the bathing experience.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

Layout and Features of a Typical Roman Bath Complex

Upon entering the baths, visitors would first disrobe in the apodyterium, the changing room. This communal space allowed individuals to remove their clothing and store their belongings securely. It was customary for bathers to assign their garments to a designated slave or attendant, ensuring their safe keeping during their visit to the baths [6].

The proceeding hall, known as the frigidarium, served as a transition space from the outside world to the interior of the baths [1]. It was a spacious and airy area, providing a visually striking introduction to the grandeur of the bath complex.

From the frigidarium, bathers would progress to the tepidarium, a warm room where they could relax and acclimate to the gradually increasing temperatures. The tepidarium often featured heated benches or lounging areas, providing a comfortable space for bathers to socialize, read, or simply unwind [2]. The walls of the tepidarium were sometimes decorated with frescoes or paintings, adding to the aesthetic appeal of the space.

The heart of a Roman bath complex was the caldarium, the hot room. This central area housed the main hot baths and was the focal point of the bathing experience. The caldarium featured pools or large basins of hot water, often supplemented by steam rooms or sudatoria [3]. The hypocaust heating system was used to maintain a constant and luxurious temperature, providing bathers with a relaxing and therapeutic bathing experience.

Adjacent to the caldarium were smaller rooms dedicated to specific activities. The sudatorium, a steam room similar to a sauna, allowed bathers to experience intense heat and perspiration, believed to have purifying and cleansing effects on the body. The laconicum, inspired by the Greek sweat baths, provided a dry and intensely heated environment for sweating and relaxation [5].

Additional spaces within a Roman bath complex included the natatio, an outdoor swimming pool, or a large basin for swimming and aquatic exercises. The natatio often featured decorative elements such as statues, water jets, and surrounding gardens, creating a serene and refreshing environment.

The architecture and design of Roman baths combined functionality, aesthetics, and technological innovations to create immersive and luxurious spaces. The meticulous planning, impressive architectural elements, and thoughtful incorporation of various features contributed to the allure and enduring legacy of Roman bath complexes [4].

The Roman Bathing Rituals and Practices

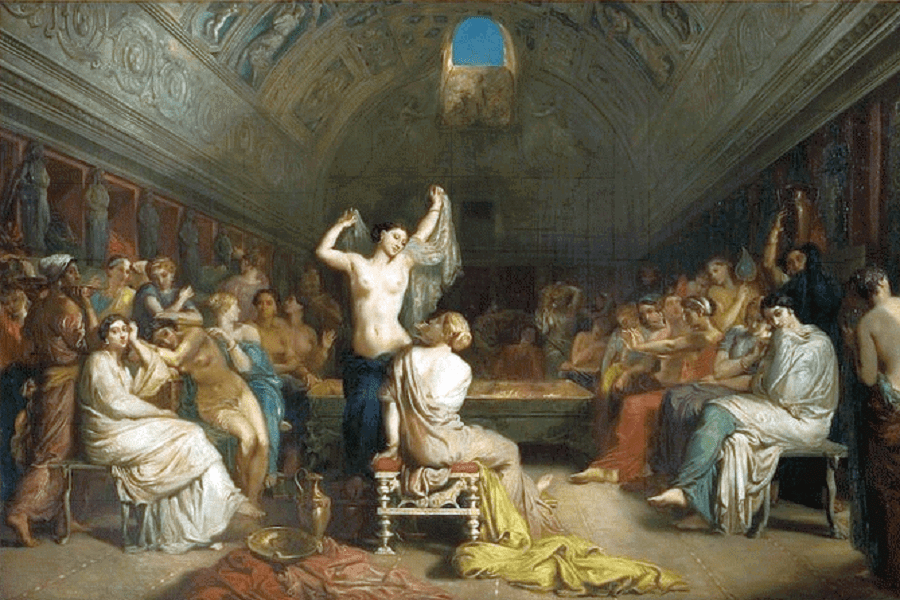

Roman baths were more than just places for bathing; they were cultural and social institutions deeply ingrained in the daily lives of the ancient Romans [1]. The rituals and practices associated with Roman baths added depth and significance to the experience, creating a holistic and immersive bathing ritual.

Social and Cultural Significance of Roman Baths

One of the primary reasons behind the social importance of Roman baths was their accessibility to all members of society. Regardless of social status or wealth, individuals could partake in the communal experience of bathing [3]. The baths provided a common ground where senators, merchants, soldiers, and even Roman slaves could come together and engage in shared activities, blurring the lines of social hierarchy.

Within the baths, people would engage in conversations, discussions, and debates on a wide range of topics. The tepidarium, with its heated benches and comfortable atmosphere, acted as a gathering place for leisurely chats and intellectual exchanges. Scholars, poets, and famous philosophers often frequented the baths, providing an opportunity for bathers to engage in stimulating conversations and gain knowledge from esteemed intellectuals [2].

Moreover, the natatio, or the open-air swimming pool, was a space where individuals could partake in friendly competitions, water games, or swimming races. These activities fostered a sense of camaraderie and created bonds among bathers. People from different walks of life would interact, support each other, and celebrate together, contributing to a stronger sense of community [2].

Cultural Practices and Activities that Took Place in Roman Baths

Roman baths were not only places for physical cleansing but also centers of cultural activities and practices. These cultural elements added depth and richness to the bathing experience, making the baths vibrant and multifaceted spaces.

One notable cultural practice in Roman baths was the presence of libraries and reading rooms. These facilities housed an extensive collection of books and scrolls, attracting intellectuals and avid readers. Bathers could immerse themselves in literature, poetry, philosophy, and historical texts while enjoying the therapeutic environment of the baths. The presence of libraries promoted intellectual pursuits and provided an avenue for self-improvement and enlightenment [4].

Artistic performances also found a place within the Roman baths. Some bath complexes had dedicated theaters or performance spaces where plays, musical recitals, and poetry readings took place [1]. Acclaimed actors, musicians, and poets would entertain the bathers with their talents, enhancing the cultural ambiance of the baths and offering moments of artistic delight [3].

Additionally, physical exercise and sporting events were common in Roman baths. The palaestra, an exercise area within the bath complex [4], featured spaces for wrestling, boxing, ball games, and other physical activities. Bathers could engage in these activities to maintain fitness, showcase their skills, and participate in friendly competitions. The palaestra served not only as a place for physical training but also as a venue for social bonding and camaraderie among athletes and spectators [3].

Religious practices also played a significant role in the Roman baths. Some bath complexes incorporated temples or shrines dedicated to Roman gods associated with health, healing, and water. Bathers would offer prayers, make votive offerings, or seek blessings from the deities before or after their bathing rituals, believing in divine protection and favor for their well-being [1].

READ MORE: Roman Religion

Therapeutic and Medicinal Aspects of Roman Baths

One of the key aspects of Roman baths was the use of different temperature zones. Bathers would start in the tepidarium to gradually raise their body temperature and induce perspiration. This process was believed to open up the pores, cleanse the skin, and eliminate toxins from the body. The caldarium, a hot room, provided intense heat that could alleviate muscle aches and promote relaxation [5]. The high humidity in the caldarium also had a positive impact on the respiratory system, potentially helping individuals with respiratory conditions breathe more easily.

The transition from the hot rooms to the frigidarium was an integral part of the bathing ritual. The sudden change in temperature was thought to stimulate blood circulation and invigorate the body [2]. This contrast between hot and cold water was believed to have a toning effect on the blood vessels, potentially improving circulation and reducing inflammation.

Mineral-rich waters were another essential element of Roman baths. Many bath complexes were built around natural springs or had water sources infused with minerals such as sulfur, iron, and calcium [2]. These minerals were believed to have specific healing properties. For instance, sulfur-rich waters were thought to be beneficial for treating skin conditions like eczema and psoriasis. Iron-rich waters were associated with improving blood circulation and overall vitality. Bathers would immerse themselves in these mineral-rich waters, believing that the minerals would be absorbed through the skin, providing therapeutic benefits [4].

Connection Between Roman Baths and Ancient Roman Medicine

Ancient Roman physicians recognized the therapeutic benefits of baths and often prescribed bathing as a form of treatment for various ailments. They believed that the combination of water, heat, and minerals could help restore the balance of bodily humor, which was believed to be responsible for maintaining health. The humoral theory, influenced by Greek medicine, suggested that imbalances in the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) could lead to illness. Bathing was seen as a way to restore harmony and equilibrium among these humors [4].

Hygiene and cleanliness were highly valued in Roman society, and regular bathing was considered essential for maintaining good health. Roman physicians emphasized the importance of bathing in preventing the accumulation of bodily impurities and removing toxins from the system [1]. They believed that regular bathing could purify the body and prevent diseases.

The communal nature of Roman baths also played a role in the connection between bathing and medicine. Bath complexes provided spaces where physicians, patients, and individuals interested in health and wellness could interact and exchange medical knowledge [1]. Discussions on medical treatments, herbal remedies, and therapeutic techniques took place within the baths [1], contributing to the dissemination of medical knowledge throughout the Roman Empire.

The Decline and Legacy of Roman Baths

One significant factor contributing to the decline of Roman baths was the decline of urban centers. With the fall of the Roman Empire, many cities experienced a decrease in population and economic activity. As a result, the maintenance and operation of public amenities, including baths, became increasingly difficult [2]. The decline of urban life meant that fewer people had access to bathhouses, leading to their neglect and abandonment.

The collapse of centralized authority in the Western Roman Empire also played a role in the decline of Roman baths. The empire’s fragmentation and the subsequent loss of strong political and administrative structures meant that there was less support and resources available for the upkeep of public infrastructure. With the decline of imperial power, the funding and maintenance of bath complexes became unsustainable, and many fell into disrepair [2].

READ MORE: The Fall of Rome: When, Why and How Did Rome Fall?

The rise of Christianity and its influence on Roman society further contributed to the decline of Roman baths. Early Christians viewed the public bathing practices in Roman baths as associated with immorality and excess [5]. The emphasis on personal purity and the spiritual aspects of Christianity led to a shift in attitudes toward communal bathing. As Christianity became the dominant religion, public bathing gradually lost favor, and private bathing became more prevalent [6].

READ MORE: How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact

Historical Impact and Legacy of Roman Baths on Western Bathing Culture

The architectural and engineering achievements of Roman baths left an indelible mark on subsequent bathing structures. The use of vaulted ceilings, heated floors, intricate mosaic designs, and water distribution systems pioneered by the Romans set the foundation for later bathing establishments [5]. For example, the ancient Roman bath concept influenced the design of medieval European bathhouses and later Renaissance baths, where similar architectural elements and features were incorporated.

The communal and social aspects of Roman baths also shaped Western bathing culture. The Roman baths served as social hubs where people from all walks of life gathered to bathe, relax, and socialize [1]. This tradition of communal bathing persisted throughout history and can be seen in the development of public bathhouses in medieval Europe, Turkish hammams, and Japanese onsen. Even today, the concept of spa resorts and wellness retreats, where people come together to enjoy shared bathing experiences, draws inspiration from the communal bathing practices of ancient Roman baths [5].

Moreover, the therapeutic and medicinal aspects of Roman baths left a lasting legacy. The Romans believed in the healing properties of water, and they utilized natural springs and mineral-rich waters in their bathing rituals [6]. This understanding of the therapeutic benefits of bathing influenced subsequent cultures and laid the foundation for hydrotherapy practices. Bathing in mineral-rich waters and thermal springs, similar to the Roman bathing traditions, became popular in various regions, such as the spa towns of Europe, where people sought the rejuvenating effects of mineral baths [6].

Modern-Day Roman Baths: Preservation and Restoration Efforts

Preserving and restoring Roman bath sites is a vital endeavor to safeguard the historical and architectural legacy of these ancient structures. Numerous organizations, archaeological authorities, and local communities are actively involved in ongoing efforts to protect and restore Roman baths around the world.

Preservation initiatives begin with thorough archaeological research and excavation. Expert archaeologists carefully unearth the remains of Roman bath complexes, meticulously documenting and analyzing each discovery [4]. This process helps reconstruct the original layout, understand the engineering techniques employed, and gain insights into the cultural significance of the baths [1].

Once excavated, the preservation process involves structural stabilization and conservation techniques. Dilapidated walls, damaged mosaics, and weakened foundations are painstakingly restored to their former glory [6]. Skilled craftsmen use traditional methods and materials to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the structures while employing modern conservation practices to prevent further deterioration.

Efforts are also directed toward enhancing the visitor experience. Interpretive displays, informational panels, and interactive exhibits are installed to provide historical context and engage visitors in the rich history of Roman baths. Virtual reconstructions, aided by advanced technology, offer immersive experiences by recreating the grandeur of these baths in their prime, allowing visitors to visualize how they would have looked and functioned [3].

The Roman Baths in Bath, England, serve as an exemplary model of successful preservation and restoration. The site showcases well-preserved Roman bathing facilities, including the Great Bath, intricate mosaic floors, and the original Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva. Ongoing conservation efforts, such as the restoration of the Roman Temple courtyard, ensure that visitors can continue to appreciate the magnificence of these ancient baths [6].

References

- Fagan, G. G. (1999). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. University of Michigan Press.

- Cunliffe, B. W. (2012). The Roman Baths and Social History. Routledge.

- DeLaine, J., & Johnston, D. E. (Eds.). (2000). Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Roman Baths. Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Yegül, F. K. (2009). Bathing in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press.

- Todd, M. 2005. ‘Baths or Baptistries? Holcombe, Lufton and their Analogues.’ Oxford Journal of Archaeology

- Rook, T. (2008). Roman Baths in Britain. Shire Archaeology.