Chinese mythology refers to the myths, legends, and folklore of the collective regions that make up modern China. Originating from rich oral tradition, Chinese mythology and the vibrant history surrounding it are eons old. Today, most of China practices some form of folk religion, Buddhism, or Taoism. Other mainstay religions include Christianity and Islam.

Table of Contents

What is Chinese Mythology?

Chinese mythology denotes the collections of myths and legends found throughout today’s Greater China regions. The mythology of ancient China survived through oral traditions and, later, through written literature. Many Chinese myths have been preserved over the centuries alongside Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism in Chinese folk religion.

What is Chinese Mythology Called?

Chinese mythology is called 中国神话, or Zhōngguó shénhuà in Pinyin. Archaic mythology has also been referred to as the ancient Chinese religion or, simply, Chinese myths and legends.

How Old is Chinese Mythology?

Chinese mythology is believed to have been established sometime in the 12th century BCE. This would align with the rule of the Shang Dynasty, China’s “first” dynasty (if we don’t count the semi-mythological Xia). While various cultures emerged from the Huang He Valley civilization, the Shang Dynasty provides the earliest archaeological evidence of a centralization of power. Therefore, the very vestiges of Chinese mythology had been cemented since the inception of Chinese civilization.

Although not the oldest mythology in the world (shout out to the ancient Sumerians), Chinese mythology is over 3,000 years old. It is amongst some of the oldest belief systems from around the world. When looking at the Xia Dynasty, one can even find evidence of a deluge myth!

READ MORE: The 10 Most Important Sumerian Gods

In case anyone was wondering, the 12th-century BCE further included the fall of Troy and the beginnings of the Olmecs. It was on the heels of the infamous Late Bronze Age collapse, which devastated the Eastern Mediterranean and surrounding regions. Despite ushering in the Greek Dark Ages, Eastern Asia appeared unaffected by the collapse of the Late Bronze Age.

Timeline of Chinese Mythology

The whole of Chinese mythology spans from 36,000 years before the creation of the Earth to around 2000 BCE. Meanwhile, some deities, specifically the Baxian, were said to have been born sometime between the Tang and Song Chinese dynasties. Ancient China only saw ten rulers across those eons, with the longest ruler being Pangu.

Celebrated Chinese Myths and Legends

Chinese mythology is the host of various, stunning tales from across the Greater China region. Myths act as a means to explain natural phenomena, give insight into human nature, explain geography, or warn of potential dangers. Every aspect of a myth from its setting to its characters further enforces the intended message. The most celebrated Chinese myths and legends have exemplary figures center stage whose virtues elevate them to national heroes.

The most famous Chinese myths and legends have been passed down over generations. Select heroes and heroines have become household names. Some tales – like the legend of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King – have become internationally known, while other myths have not yet achieved such notoriety.

- Chang’e, Hou Yi, and the Jade Rabbit

- Nuwa Saves the World

- Pangu and the Cosmic Egg

- The Eight Immortals and the Dragon King

- The Legend of Nezha

- The Legend of Nuwa and Fu Xi

- The Lotus Lantern

- Yu the Great Tames the Great Flood

What are the 4 Chinese Myths?

The myths that makeup China’s 4 Great Folktales include:

- Lady Meng Jiang

- The Butterfly Lovers

- The Legend of the White Snake

- The Weaver Girl and the Cowherd

The above myths are amongst the most well-known of the folktales that make up Chinese culture. However, they are just a small sample of the brilliant myths found throughout Chinese history. The Four Great Folktales were brought front and center in between 1918 and 1926 during the Modern Chinese Folklore Movement. From then on, scholars from around the globe have recognized the value of the Four Great Folktales in broader Chinese culture.

Important Locations in Chinese Mythology

One doesn’t have to be a writer, educator, or creative to know that settings are an integral part of storytelling. That being said, locations in Chinese mythology offer invaluable insights into ancient Chinese understandings of the world around them. From sacred mountains to mystical islands, the locations of Chinese myths were thought to be real, accessible places.

Several places in mythology are thought to represent real locations. Much like other ancient civilizations, places beyond easy reach were interpreted as being shrouded in mystery; fanciful depictions tend to triumph over fact. However, as with any other world mythology, Chinese culture includes locations that are generally only accessible once certain conditions are met (such as dying). Nowadays, the consensus is that the Chinese believed in three primary cosmic domains: the Heavens, Earth, and the Underworld.

- Diyu

- Youdu

- Fusang

- Guixu

- Penglai

- Queqiao

- The Black River

- The Eight Pillars

- The Four Seas

- The Moving Sands

- The Red River

- The Weak River

- Tiān

- Xuanpu

- Yaochi

Gods and Goddesses of the Chinese Pantheon

Chinese mythology is filled with distinguished deities, spirits, and otherworldly beings alike. They appear in myths and Chinese literature, fulfilling the roles of both heroes and antagonists. Many stories actually dispel the mystery around how some gods become gods, such as the tale of Chang’e, thereby achieving what many mythologies struggle with acknowledging that deities were somewhat human, too.

Chinese gods and goddesses were known to be powerful, but not wholly invincible. Despite their divine nature, they had been bested several times. Most, if not all, Chinese deities were immortal and eternally youthful (unless stated otherwise). It is immortality that led to the ascension of several key deities in the pantheon, most famously the Baxian.

A fraction of the illustrious Chinese pantheon and four significant collections as they are known in mythology include:

- Bi Gan

- Bixia

- Caishen

- Chang’e

- Changxi

- Lei Gong

- Dianmu

- Doumu

- The Dragon King

- Erlang Shen

- Guanyin

- Jiutian Xuannu

- Lu Ban

- Mazu

- Meng Po

- Nezha

- Nuba

- Pangu

- Shennong

- Sun Wukong

- Wenchang Wang

- Wufang Shangdi

- Xihe

- Xiwangmu

- Yan Wang

- Yue Lao

- Yu Shi

- Zao Jun

- Zhong Kui

- Zhu Rong

The Sanguan Dadi

In Chinese mythology, the Sanguan Dadi are three officials appointed by the Jade Emperor to rule over Earth. Each was assigned their own piece of Earth to oversee. In their respective realms, they have complete control. They watch over mankind and their domains, reporting back to the Jade Emperor when necessary.

In Taoism, the Sanguan Dadi are believed to hold immense power, largely due to their Fates-like ability to see the lifespans of all mortals. However, they were distinct from the Three Pure Ones, who were quite literally embodiments of the past, present, and future. The Sanguan Dadi have also been known as the Three Officials.

- Tian Guan (Ruler of Heaven)

- Di Guan (Ruler of Earth)

- Shui Guan (Ruler of Water)

The Menshen

The Menshen are two deities or spirits that act as the guardians of doorways. Traditionally, they protect occupants from demons, evil spirits, and bad omens. Each one would flank one side of a traditional double-door entrance into residences. After the practice gained popularity throughout China, a third deity was added to guard a home’s back door.

The imagery of the Menshen can be found in private dwellings and temples alike. More often than not, they are depicted alongside fearsome tigers that are described as their pets. Far from cute cats, the tigers were said to be sustained off the bodies of those evil-doers ensnared by the Menshen. It’s safe to say trespassing had some dire consequences.

- Yu Lei

- Shen Tu

- Zhong Kui

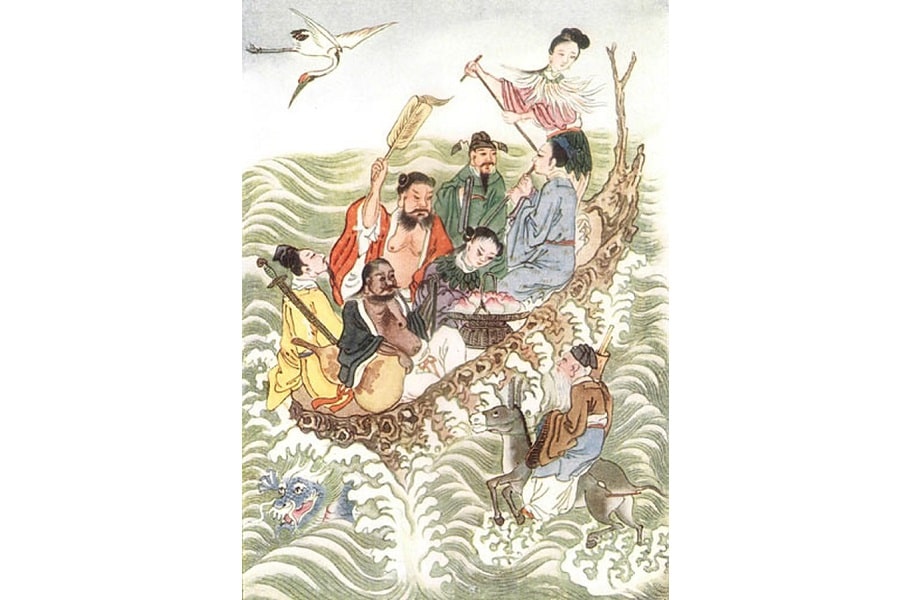

The Eight Immortals

The Eight Immortals are eight individuals that ascended to godhood post-mortem. Now, they aren’t the only ones to have achieved immortality after facing a mortal death in Chinese history. They are, however, the most ready to offer assistance to those seeking it.

- Zhongli Quan

- He Xiangu

- Lu Dongbin

- Zhang Guo Lao

- Cao Guojiu

- Han Xiang Zi

- Lan Caihe

- Li Tai Guai

The Three Pure Ones

In Taoism, the Three Pure Ones are considered the three most powerful deities. It was said they could each manipulate time in various ways. So much so, they were thought to embody the past, present, and future.

Daode Tianzun is considered to be an incarnation of the great philosopher Laozi and each Pure One is counted as a physical manifestation of the Tao. Usually, the Three Pure Ones are depicted as elderly sages seated upon thrones; the oldest being Daode Tianzun. From their divine thrones, they each oversaw the functionings of three different heavens: Yu-Qing, Shang-Qing, and Tai-Qing, respectively. Taoism dictates that there were 36 heavens (called tiān) that were organized into six separate levels.

- Yuanshi Tianzun

- Lingbao Tianzun

- Daode Tianzun

READ MORE: History’s Most Famous Philosophers: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and More!

How Many Chinese Gods are There?

There are well over 200 Chinese gods. In ancient Chinese culture, there was a devoted veneration of gods, spirits, and ancestors. Thus, ancient Chinese religion was extensively polytheistic, with various regions having their own divine hierarchy and religious practices.

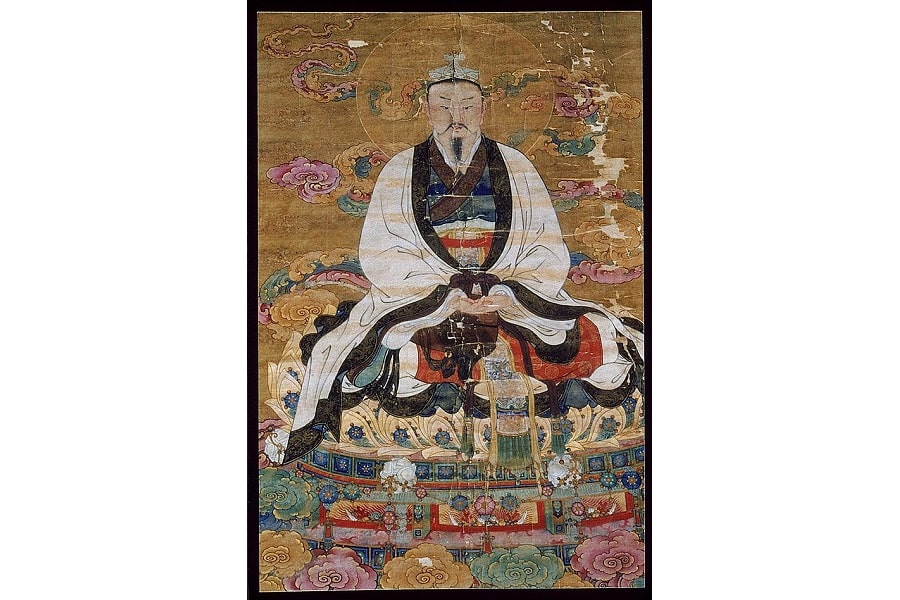

Who is the Main God of China?

The main god of Chinese folk religion is the Jade Emperor. The Jade Emperor has not always been the supreme deity of the Chinese pantheon, however. There have been at least two other supreme deities throughout the long history of Chinese mythology.

The first of which, Shang Di, was the god of weather and victory. He was the chief deity during the Shang Dynasty of ancient China. Yuanshi Tianzun rose to preeminence thereafter, sometime in the Zhou Dynasty. Meanwhile, the Jade Emperor became the supreme deity during the rule of the Song.

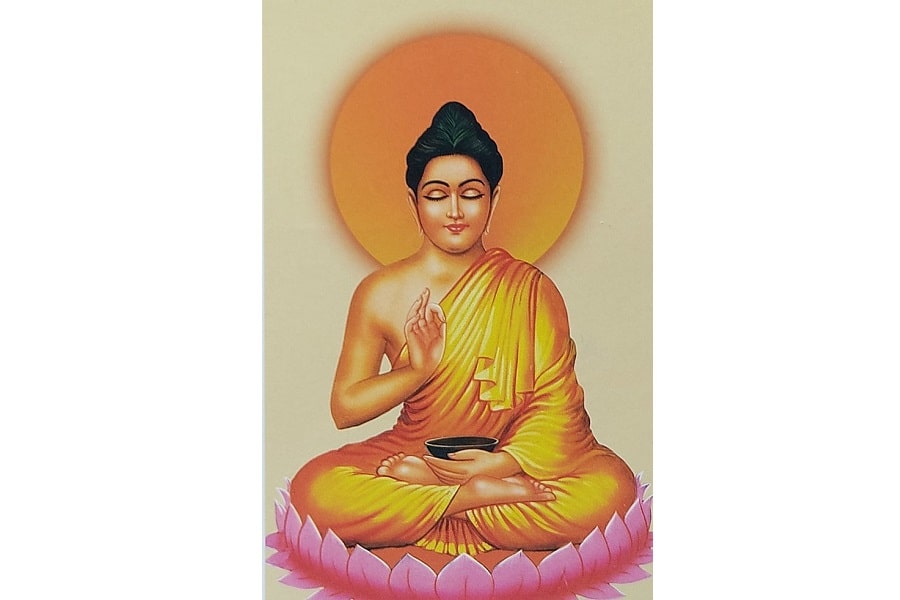

There has also been much discussion among scholars and theologists on beings that are higher than the gods, such as the Buddhas. Entities that are entirely enlightened and thus naturally above any sort of deity. Part of this discourse is explored in Journey to the West, in which the Jade Emperor goes toe-to-toe with the Buddha and loses significantly.

For anyone wondering, that isn’t a normal day for them: the antics of a certain Monkey King are to thank for that skirmish.

Who is the Most Powerful Being in Chinese Mythology?

By most accounts, the Jade Emperor is the most powerful being in Chinese mythology. The god is known as the chief deity of the pantheon, having been the only one powerful enough to triumph over evil. However, with the inclusion of Buddhism, Gautama Buddha is a more powerful being than the Jade Emperor.

All things considered, the most powerful Chinese god is the Jade Emperor. The Buddha, and incarnations of the Buddha, are not generally considered to be gods. Since he’s disqualified from godhood, Buddha can’t be the most powerful Chinese god, but he’s still counted as the most powerful being.

Religious Practices and Beliefs of Ancient China

The religious practices and beliefs of the Huang He Valley civilization helped shape early Chinese culture. Early, extensive interaction between Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and folk beliefs have all played a significant role in developing the religious profiles of ancient Chinese people. Markers of ancient folk beliefs have survived into today’s religious traditions found throughout Greater China.

Festivals

Festivals of ancient China would have been celebrated across the Chinese lunar calendar. In fact, while most of China today adheres to the Gregorian calendar, all traditional festivals, holidays, and celebrations are still dictated by the lunar calendar. These celebrations are relegated to certain days or, considering Ghost Month, throughout a specific month.

- The Spring Festival/Chinese New Year/Lunar New Year(春節)

- The Yuan-Xiao Festival/Lantern Festival (元宵节)

- The Monkey King Festival (齊天大聖千秋)

- The Qingming Festival (清明節)

- The Hungry Ghost Festival (中元节)

- The Dragon Boat Festival (端午節)

- The Chongyang Festival (重陽節)

- The Qixi Festival (七夕)

- The Cheung Chau Bun Festival (包山節)

- The Moon Festival (中秋節)

- The Dongzhi Festival (冬至)

Cults and Mysteries in Ancient China

Religious cults hold immense social and political sway in all societies they have manifested in. In the religious tradition of ancient Chinese societies, cults were both state and regional collectives. Some even grew to the point of gaining enough martial power to threaten government structure and national stability.

Within the ancient Chinese civilization, theological schools of thought were usually divided between Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and animistic folk religions. As Homer H. Dubs asserts in “An Ancient Chinese Mystery Cult” per the 1942 Harvard Theological Review, not all beliefs viewed one another as equal. That does not discount their cooperation and influence on wider Chinese religion.

Cults in ancient China were built around the worship of specific, powerful deities. The cult of the Queen Mother of the West, Xiwangmu, was especially popular as she was a deity that had no clear beginning and no obvious end. She was prayed to for longevity, fertility, and rain, and had a seemingly popular following as a goddess within Taoist belief.

Sacrifices

Chinese folk religion has an extensive, complex history with sacrifices. Based on the earliest records available to academics, sacrifices date back to the Shang Dynasty. The Shang Dynasty has the most abundant evidence of ritual sacrifices, particularly found inscribed on oracle bones. Such is not to say that earlier cultures before dynastic rule did not participate in sacrifices; there’s simply not a firm answer.

Human sacrifices were common throughout the Shang Dynasty, where burial practices were routinely practiced among Shang elites. Usually, two types of human sacrifices were performed: those buried in mass graves with little-to-no grave goods (rensheng) and those sacrificed as companions for the deceased (renxun). Those sacrificed as rensheng were oftentimes beheaded before burial, with their heads buried separately from their bodies. Puppies were also frequently sacrificed in middle-class Shang burials.

Translated evidence from oracle bones confirms that livestock such as oxen and sheep were sacrificial favorites. Interestingly enough, diviners were oftentimes charged with asking spirits what their preferred sacrifice was when given choices. After all, sacrifices ensured appeasement. One would certainly need to know if their sacrificed sheep would satiate the entity they are seeking guidance from.

The most common sacrifices that are detailed in Chinese mythology are meal sacrifices, which are especially highlighted in the Hungry Ghost Festival, the Chongyang Festival, and the Qingming Festival. Sacrifices of food are exclusive to ancestral veneration. Traditional foods and meals that were favored by the deceased are popular offerings. Alongside meal sacrifices, joss paper (alternatively, incense) is also commonly burned.

Heroes and Legendary Figures of Chinese Legend

Within Chinese mythology, heroes – and heroines – are found in many important myths. They are recognizable for the standout traits that have grown to define them. The traits that legendary heroes embody are still reflected in modern Chinese cultural values. These values affect everything from interpersonal relationships to foreign policy.

The most iconic heroes of Chinese mythology are those individuals who are exemplars of morality. Traits that align with the Confucian Eight Virtues (loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, love, honesty, justice, harmony, and peace) are oftentimes found in Chinese heroes of eld. The Four Cardinal Principles (propriety, integrity, righteousness, and shame) are also featured in various myths and legends.

- Cangjie

- Chiyou

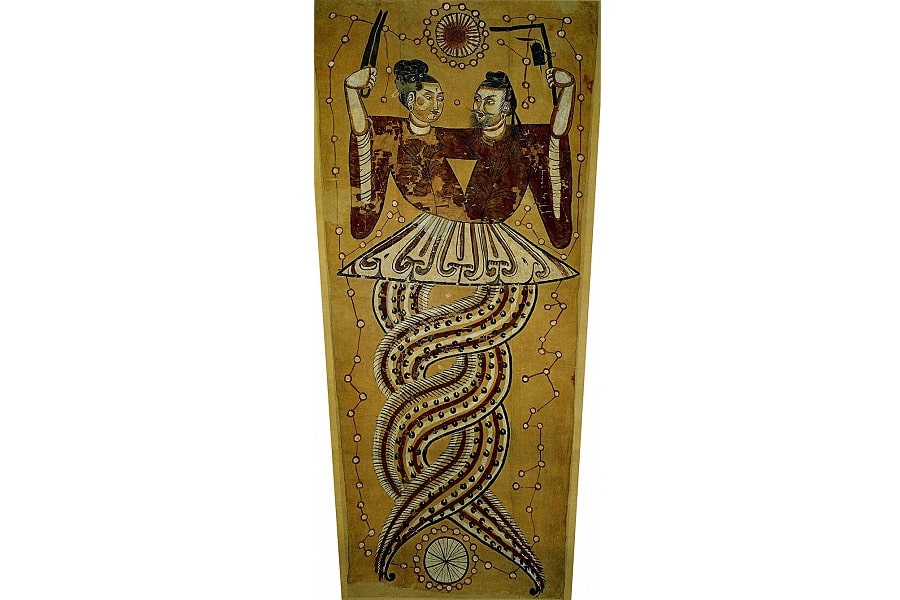

- Fu Xi and Nuwa

- Gun

- Hou Ji

- Hou Yi

- Hua Mulan

- Ji Gong (Daoji)

- Wenshu (Bodhisattva Manjushri)

- Yue Fei

Additional legendary figures in Chinese myth and legend include the legendary emperors’ Di Jun and Da Yu. These emperors are featured in vital myths, such as the origin story of the sun and the founding of the Xia Dynasty.

Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors

The Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors ruled in the time before the Xia Dynasty. Since we aren’t even sure that the Xia existed, it is unlikely that these mythological figures walked the earth. Nonetheless, they are crucial aspects of Chinese mythology and act to explain the state of the world as the Chinese people knew it.

Ancient myths recount Three Sovereigns – mythological rulers that were either demi-gods or deified kings – who ruled during periods of peace. They also are said to have wielded great divine power, apparently enabled through the Tao. Different sources identify different beings as Sovereigns. While Fu Xi, Nuwa, and Shennong are oftentimes the ones believed to be the Three Sovereigns. All potential Sovereigns below include:

- Earthly Sovereign

- Fu Xi

- Gong Gong

- Heavenly Sovereign

- Human Sovereign

- Nuwa

- Shennong

- Suiren

- The Yellow Emperor

- Zhurong

On top of the Three Sovereigns, there are also myths regarding the Five Emperors. These mythological characters were cited as having offered major contributions to society. Again, there’s conflict in sources as to just who was considered one of the Five Emperors. All potentials include:

- Emperor Ku

- Emperor Yao

- Jin Tian

- Shun

- The Yan Emperor

- The Yellow Emperor

- Zhuanxu

Heroes of the Three Kingdoms Era

There have been no heroes as fanatically discussed and dissected across the globe as the heroes of China’s Three Kingdoms Period. Various literature and media that has been released over the years showcasing the heroes of the Three Kingdoms, with the most recent addition being the video game Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty.

The Three Kingdoms era historically took place between 222 and 280 CE. On the heels of the Eastern Han Dynasty, the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu emerged. Though later absorbed into the Western Jin Dynasty and lasting less than 60 years, the Three Kingdoms left a lasting impact on the Chinese people. The events of the Three Kingdoms Period are famously immortalized in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong.

- Guan Yu

- Liu Bei

- Zhang Fei

- Cao Cao

- Zhuge Liang

- Sun Quan

- Zuo Ci

- Lu Bu

Who is the Most Famous Chinese Hero?

The most famous Chinese hero is Yue Fei, the legendary general turned national hero during the Song Dynasty. Heroes in Chinese culture are often seen as the pinnacle of moral uprightness. Indeed, Chinese heroes of ancient times were bestowed with certain virtues – so much so, that many evolved into embodiments of these traits.

Yue Fei, who is also known by his courtesy name Pengju, led the Song army in the Jin-Song Wars (1125-1234 CE). Twenty-one years after his death, a temple and mausoleum in Hangzhou were erected in his honor. He is synonymous with fealty; posthumous honors are emphasized thus, with Yue earning the title of Wumu (“Martial and Stern”). If that isn’t enough to convince you of this man’s loyalty, legends say he also had a pretty sick back tattoo that read “serve the country with the utmost loyalty” (盡忠報國).

Mythological Creatures in Chinese Mythology

Mythical creatures are among the most famous aspects of Chinese legends. Some are auspicious in their existence, with their presence being enough to bring good fortune. Others thrived in chaos and acted as harbingers. The most prominent mythological creatures found in Chinese folk beliefs are:

- Ao

- Bi Xi

- Dapeng

- Dai

- Fenghuang

- Huli jing

- Huxian

- Jin Chan

- Jiutou Niao

- Kui

- Longma

- Pixiu

- Qilin

- Sons of the Dragon*

- The Fu Dog

- Xiezhi

- Zhulong

*The Sons of the Dragon are the nine mythological offspring of the legendary Dragon King; they include dragons Bi’an, Bixi, Chaofeng, Chiwen, Pu Lao, Qiuniu, Suanni, Xixi, and Yazi

The Four Celestial Animals and the Five Heavenly Beasts

The Four Celestial Animals and the Five Heavenly Beasts are celestial mythical creatures that appear predominantly in Chinese mythology. The Five Heavenly Beasts expand upon the Four Celestial Animals by adding one to the central point: the Yellow Dragon.

Chinese celestial animals are found in the constellations within Chinese astronomy. They are associated with the four cardinal directions and have their own symbolic colors. The Four Celestial Animals are further known as the “Four Auspicious Beasts.” Usually, these mythical creatures are found within the principles of Feng Shui.

- Baihu (White Tiger of the West)

- Qinglong (Azure Dragon of the East)

- Zhuque (Vermilion Bird of the South)

- Xuanwu (Black Tortoise of the North)

- Qilin (Yellow Dragon of the Center)

Monsters of Chinese Myth

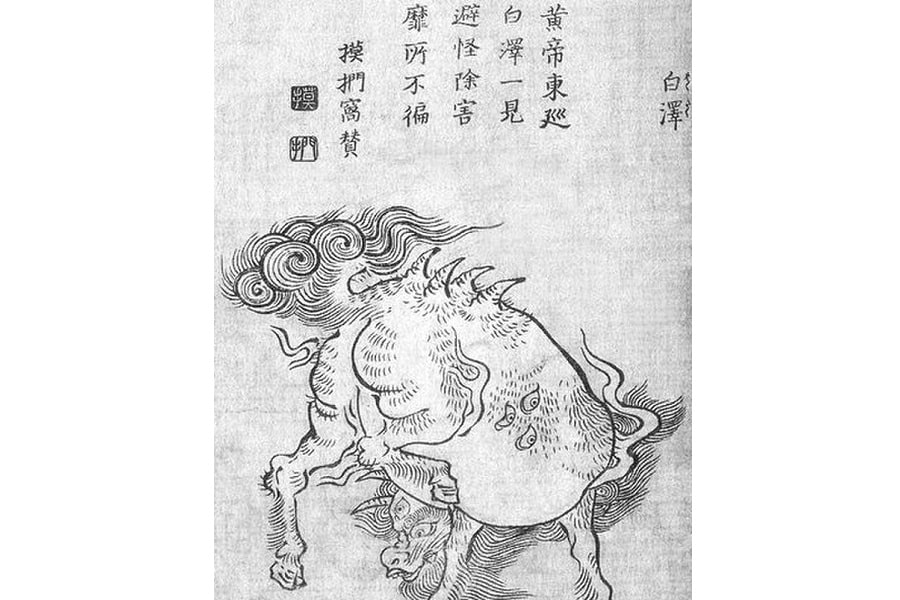

The monsters of Chinese myth are some of the most frightening creatures to come from world mythologies. Though many appear as restless ghosts and spirits of those who died a violent death, others are straight-up monstrosities. Oh, there are vampires, too!

In Chinese mythology, monsters were a means to explain the frightening, the unknown, and the unexplainable. They also were a means to further philosophical and theological doctrines, such as offering a look into the afterlife.

- Ba Jiao Gui

- Bai Ze

- Bashe

- Di Fu Ling

- Diao Si Gui

- Feng

- Guei

- Gui Po

- Huodou

- Jiangshi

- Mogui

- Nan Gui

- Nian

- Nu Gui

- Shen

- Shui Gui

- The Four Perils*

- Yaogui

- You Hun Ye Gui

*The Four Perils are Hundun, Taotie, Qiongqi, and Taowu; they are malevolent and are in direct opposition to the Four Auspicious Beasts

Legendary Items from Chinese Mythology

The legendary items from Chinese mythology add a lot to its already rich lore. They raise the stakes in any confrontation and can turn the tide of wars at a drop of a hat. However, not all mythical artifacts are weapons. For example, the Peaches of Immortality grant a long life to those who consume them, while the Tea of Forgetfulness allows spirits to be reincarnated with a clean slate.

Many items are described in larger detail in great literary works like Investiture of the Gods and Journey to the West. Given the absolute heights that the Three Kingdoms Period has been lifted thanks to Romance of the Three Kingdoms, some of those heroes’ weapons are on our list, too. Now before we jump to it, note that a ton of legendary artifacts from Chinese mythology belong to either Laozi, Sun Wukong, or Nezha. You know, the young warrior god had a bit of a reputation for hoarding, so it’s no surprise, really.

- Five Flavored Tea of Forgetfulness

- Jiang Ziya’s Fengshen Bang

- Nezha’s Armillary Sash

- Nezha’s Leopard Skin Bag

- Peaches of Immortality

- The Axe of Pangu

- The Bajiao Shan of the Princess of the Iron Fan

- The Da Shen Bian

- The Dragon Binding Rope

- The Golden Chalice of Primordial Chaos

- The Guan Dao

- The Huohuan Bu of Mount Kunlun

- The Lotus Lantern

- The Ocean Calming Pearls

- The Shanhe Sheji Tu of Nuwa

- The Somersault Cloud of Sun Wukong

- The Tree of Seven Treasures

- The Twin Swords of Liu Bei

- The Wheels of Fire and Wind

- Xirang (Swelling Earth)

Famous Literature Featuring Chinese Mythology

Surprisingly, the most famous writings that deal with Chinese mythology aren’t books. Oracle bones dated back to the 2nd millennium BCE are the earliest evidence of Chinese religious ideas as expressed in a script. That being said, serious literary undertakings didn’t quite come underway until the invention of paper by Cai Lun in 105 CE. Afterward, religious attestations were documented and later printed, en masse.

- Journey to the West (1592)

- I Ching/Book of Changes (9th Century BCE)

- Fensheng Yanyi/Investiture of the Gods (16th Century CE)

- Romance of the Three Kingdoms (14th Century CE)

- Dream of the Red Chamber (1791)

- Shan Hai Jing/The Classic of Mountains and Seas (between 4th-century BCE and 14th-century CE)

- Table of Peerless Heroes (1694)

- Romance of the Three Kingdoms (1522)

- The Spring and Autumn Annals (722-481 BCE)

Ancient Chinese Mythology Artwork

Unsurprisingly, the belief systems within a culture significantly impacted the art that was created. Akin to the artistic traditions of the Western world, religion heavily influenced literature, art, and architecture in ancient China. Ridge beasts are a staple in the Forbidden City of Beijing, while more clear-cut Chinese mythology art could be found in paintings like the Peach Festival of the Queen Mother of the West.

The earliest art that emerged from the cultures of the Huang He Valley civilization were artifacts made of stone and various ceramics. In fact, the oldest piece of Chinese artwork is a 13,500-year-old bird figurine made out of blackened bone. The Bronze Age was in full swing by the Shang Dynasty, which saw the craftsmanship of exquisite metal works, like this ritual hu among others.

The Theater Behind Chinese Mythology

Chinese theater has an extensive history, dating back thousands of years. Most performances are musically rich as reflected in xiqu, or traditional Chinese opera. Although an integral piece of ceremonies and worship, Chinese theater didn’t wholly develop into what we know it until the 12th century CE.

At its inception, theatrical performances were staged to please the gods. There were shamanic performances, dances for rain, and performances to celebrate victories in battle. Theater later grew into entertainment; first for nobility, then for the common man. As Chinese theater developed, so did the messages it attempted to convey. What was once exclusively used for prayer became a means of pleasure as comedies, tragedies, and dramas grew in popularity.

Regions throughout Greater China have unique operatic forms. Variations can be found in the music, delivery, costume, and other stylistic approaches of the theater. The few operatic traditions that rose to national fame include Peking opera, Henan opera, Yue opera, Huangmei opera, and Pingju opera. The She Xi ritual opera is staged to specifically honor the gods, whether during festivals, celebrations, or divine birthdays by reenacting certain famous myths.

Chinese Myths and Legends as Seen in Popular Media

Nowadays, one can find Chinese myths and legends anywhere from the big screen to their television. Some of the most popular myths have multiple adaptations, such as the legendary Ballad of Hua Mulan, whose Disney adaptations have stirred up controversy more than once. It’s also impossible to forget hit Chinese dramas, like Legend of Nine Tails Fox (2016) and Legend of the White Snake (2019), whose beautiful settings and costumes immerse the viewer in the many myths found in Chinese history.

- Journey to the West (2013)

- Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2021)

- Journey to the West (1996 television series)

- Seventh Moon (2008)

- I Am Nezha (2016)

- Jiang Ziya (2020)

It goes without saying, familiar stories are the ones that gain the most traction. And, what tends to be the case with most mythological retellings, the cream of the crop tends to be the ones made by folks with a solid understanding of the material. When it comes down to Chinese mythology and its representation in popular media, we can look to Chinese creators for the most faithful depictions.