Are you still looking for a being that caused a solar eclipse? Well, look no further, because Quetzalcoatl is your guy. While at first a fully zoomorphic feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl would later be represented in his human form. The worship of Quetzalcoatl is wide-reaching, has a rich history, and exemplifies the complex world of Aztec mythology.

Table of Contents

What Was Quetzalcoatl the God Of?

Quetzalcoatl played many roles in ancient Aztec mythology, so it’s difficult to pin down just one. In general, he is considered the god of wisdom, the god of the Aztec ritual calendar, the god of corn and maize, and oftentimes a symbol of death and resurrection.

The different roles of Quetzalcoatl are partly attributable to a series of reincarnations. Like many other Mesoamerican deities, the story of our god sees several reincarnations.

As a god, it’s only logical that such reincarnations would be for the betterment of the earth and its people. This ‘betterment’ meant something different with every new installment, which explains why many Aztec deities are related to different realms.

Initial Worship of Quetzalcoatl

So it should be clear that Quetzalcoatl was, indeed, a great mythical figure. Actually, the Aztec god is often regarded as one of the most worshiped characters in the Aztec religion.

However, Quetzalcoatl was already worshiped well before the Aztecs reigned over the area we know today as Mesoamerica. Or, more appropriately, Abya Yala.

Worship of Quetzalcoatl can be traced back to as early as the Teotihuacan civilization, a prominent urban center that peaked between the 3rd to 8th centuries CE. The Toltecs and Nahuas worshiped the god before he was eventually adopted by the Aztecs.

The Name Quetzalcoatl

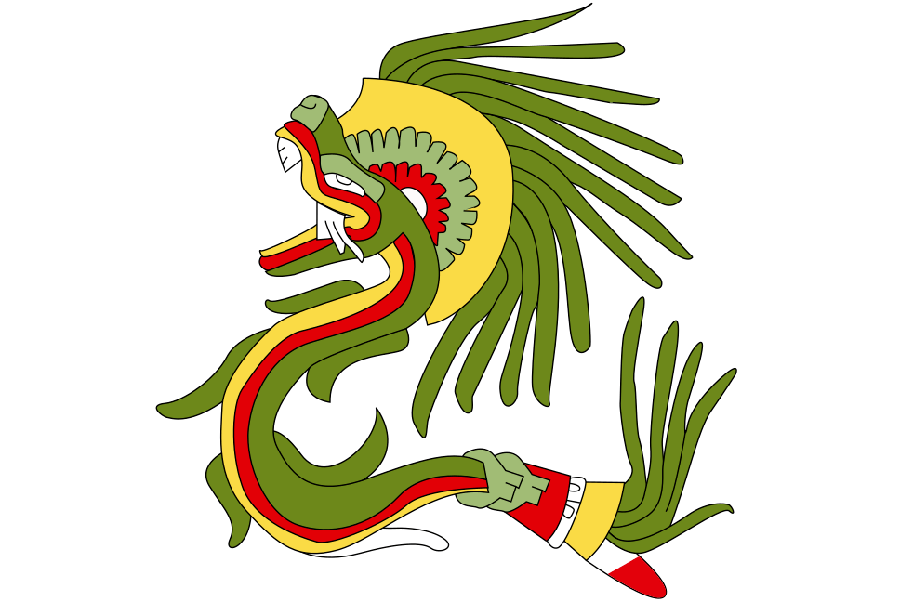

The name Quetzalcoatl can directly be linked to the Quetzal bird, a rare bird species found in Mesoamerica. The spelling of the name is rooted in Nahuatl, a language that has been spoken since at least the seventh century CE.

The first part comes from the Nahuatl word quetzalli, meaning ‘precious green feather.’ The second part of his name, coatl, means ‘serpent’. So Quetzalcoatl is named after the thing he looks like, a feathered serpent deity. It is not a coincidence that Quetzalcoatl is just as often referred to as the Feathered Serpent by his worshipers and historians.

Why is the Feathered Serpent God Important in Aztec Culture?

Quetzalcoatl is but one of the Aztec gods and goddesses that has animal-like characteristics. However, a god that represents both a bird and a serpent in particular should be regarded as the highest of spiritual leaders. Why is that? Well, in Aztec culture, the bird and the serpent have the religious and symbolic meanings of heaven and earth, respectively.

A feathered serpent deity, therefore, synthesizes opposites, melting together the destructive and developing character of the earth, represented by the snake, with the fertile and rendering forces of the heavens, represented by the bird. This, too, can be seen in the birth of Quetzalcoatl.

The Birth of the Feathered Serpent

Quetzalcoatl was a jack of many trades, a truth also reflected in the stories surrounding his birth. Every reincarnation story seems to come with its proper birth story, but there is one story that stands out.

It starts with Tlaloc, the Aztec god of rain. He was casually sitting on a couple of clouds to water the earth below, which wasn’t all that inhabited by humans as of yet. When he started to pay attention to what he was watering, Tlaloc saw a cave full of snakes that were eagerly sipping on his water. All but one.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

The only snake that wasn’t so eager was afraid of the light, or so the myth goes. Residing in the darkness felt safe to him, so he decided to stay far away from the life-giving water.

READ MORE: Water Gods and Sea Gods From Around the World

Tlaloc is Curious

Of course, the odd one out sparked the interest of Tlaloc. In fact, he wanted to tempt him to come out into the light. There was one way that would certainly work, namely by letting it rain so abundantly that the snake simply drifted out of the cave. Indeed, it turned out that this was the only viable option since the snake wasn’t planning on moving for other reasons.

After months of rain, the snake was forced to come out of the cave. And, it wasn’t so bad after all. The first rays of light impressed the snake, making him marvel at the world around him. Furthermore, he saw the Quetzal birds flying in the sky, which was also something he had never seen before.

Amazed by the grace and beauty of the birds, the snake decided his destiny was to fly like them. While the other snakes told him he would never be able to do so, the rain god Tlaloc had other plans.

From Snake to Feathered Serpent

Getting the snake out of the cave had been Tlaloc’s only objective for months on end. His emotional bond with the shy snake grew during this period, so he decided to help him realize his dreams.

Tlaloc blew the snake into the air, to a point where he was higher than the birds. Having been in awe of the sun and its light, the snake decided to fly toward the sun. In fact, he flew straight into it, leading to a total eclipse.

All good eclipses must come to an end, and this happened when the snake evolved into a Feathered Serpent and flew out of the sun again. He was quite a bit bigger than he was before.

Indeed, Quetzalcoatl was born. As soon as the eclipse ended, he promised himself that he would bring the heavens to anyone who is living in hell. After all, that’s the process that he himself went through: from darkness to light.

How Quetzalcoatl Created and Sustained Humans

The eclipse that was caused by the birth of Quetzalcoatl is believed to be the fifth eclipse to ever happen. Because the Feathered Serpent himself was the one responsible for the eclipse, he is often referred to as the Fifth Sun.

READ MORE: Sun Gods: Ancient Solar Deities From Around the World

The four suns before Quetzalcoatl had been destroyed by disastrous events, like floods, fires, and volcanic eruptions. Based on the birth story of Quetzalcoatl, it seems safe to assume that the fourth sun was destroyed because of the floods caused by Tlaloc.

The floods, too, caused great disaster to the earth in general. But, remember, the promise of Quetzalcoatl was to bring heaven to the beings that were living in hell. While in his own story, this was not all too literal, his actions that followed were actually the literal interpretation of his promise.

How Did Quetzalcoatl Create Humans?

After the eclipse of the fourth sun, Quetzalcoatl would go on a trip to the underworld. In the underworld, Quetzalcoatl went all the way to Mictln; the lowest region of the Aztec underworld. Here, our plumed serpent gathered the bones of all the previous races that walked the earth. By adding a bit of his own blood, he allowed a new civilization to emerge.

READ MORE: 10 Gods of Death and the Underworld From Around the World

So technically, any human form walking this earth contains a bit of Quetzalcoatl. For this reason, it is also believed that offers to Quetzalcoatl were one of only a few that should not include human sacrifice. Because, if they did include human sacrifice, basically a part of Quetzalcoatl himself would be killed in order to honor him. What a conundrum.

His representation of heaven and hell is also interpreted in different realms. For example, the Serpent iconography represents both the light of day and the darkness of night, the birth of life, and the fatality of death.

The People of the Corn

Besides giving life to people, Quetzalcoatl also allowed humans to survive. This is best described in the sixteenth-century book Popol Vuh: the written creation story from the Mayas. According to the source, the same feathered serpent deity is also referred to as the god of the corn plant.

That’s quite a big deal, because for the people in ancient Mexico, maize, or corn, is not just a crop. In fact, it is a deep cultural symbol that is intrinsic to daily life. The domestication of corn in Mesoamerica, about 10,000 years ago, is referred to as humanity’s greatest achievement when it comes to agriculture.

A wide range of maize crops are still eaten to this date, both by the Mexicans that have adopted many of the European habits, and the remaining Indigenous peoples of central Mexico. Have you ever eaten blue, white, black, or red corn? Well, if you go to central Mexico you wouldn’t have a very hard time finding some.

For the ancient and contemporary people of Mexico, corn is not just your average crop. It allows for a form of food security, and therefore for peace, and as a result, has taken on not only physical and economic importance but spiritual significance as well. It is believed that the Feathered Serpent was responsible for all of it.

The Legend that Links Quetzalcoatl to Corn

But still, how could that ever be the case? Sure, we understand that corn is all these things, but was Quetzalcoatl just ‘given’ the status of the god of corn in ancient Mesoamerican culture? Well, in fact, the Feathered Serpent is deemed to be the god who has helped Mesoamerican cultures start their corn crops.

Quetzalcoatl became linked with the maize crop thanks to ancient legends. According to stories, Aztec people only ate animals or roots until Quetzalcoatl arrived. Or rather, arrived again.

The Quest for Corn

Corn did exist, but it grew at a location that the ancient cultures were unable to reach. Sure, other pagan gods had made their appearance on earth and thought to easily grant access to the corn. However, each and every god had failed terribly in doing so.

The Aztecs eventually called Quetzalcoatl for help. Remember, he has already been deemed a god. But also, his role and what he represented changed during every installment of his being.

Divine messengers would talk with the god, asking for assistance in reaching the other side of the mountain: the location of the corn. Because of this, the latest reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl would come to earth to do exactly that.

While other gods had relied on brute force for reaching the other side, Quetzalcoatl relied on intelligence in order to reach the maize. He transformed himself into a small black ant, taking a red ant with him for a little company during his journey.

The trip was far from easy, but Quetzalcoatl was able to complete it. Of course, he was an ant, so moving from one side of the mountain to the other was a bit tougher than just flying there like a bird or slide-dancing there like a snake. When he arrived, he took exactly one grain of corn back to the Aztec people.

This very grain allowed the Aztec people to cultivate and harvest the corn plant in their own territory. Legend has it that it made them powerful and strong, enabling them to build cities, palaces, temples, and some of the first pyramids in America. It really elevated the status of the Feathered Serpent to the protector of the people, which is also affirmed by his role as patron god.

Quetzalcoatl and the Tezacatlipocas

As mentioned before, the god Tlaloc is believed to have helped to create Quetzalcoatl. Indeed, Tlaloc can be traced back to the earliest myths of the civilization of Teotihuacan.

The Aztecs weren’t a big fan of chronological order and shook up the world of the gods. They kept the same gods but believed in a new story. While the inhabitants of Teotihuacan were the first ones to worship Quetzalcoatl, the Aztecs reinterpreted him over time.

A Shift in Perception of Quetzalcoatl

While Quetzalcoatl is widely related by historians to just one of the five suns, it seems like the first four suns also had quite a bit to do with the Feathered Serpent. That is, according to the Aztecs.

The relation of Quetzalcoatl with just the latest sun is a result of the mingling of his earliest myths and some new perceptions. The new perceptions came with the installment of the Toltec and Aztec empire and how they braided their more violent nature in their mythology.

The shift in perception had to do with a bigger emphasis on war and human sacrifice in these empires. Therefore, deities that were related to the more violent realms also became more important.

Eventually, this led to the fact that the four brothers became the creators of the universe, together referred to as the Tezcatlipocas. Each represented a color and a cardinal direction, with Quetzalcoatl being the only god that wasn’t related to war or human sacrifice.

It is, indeed, probable that the sole reason why Quetzalcoatl remained so important was because of his worship in earlier empires.

How Quetzalcoatl Became Part of the Tezcatlipocas

The Aztecs did have their own story surrounding Quetzalcoatl becoming one of the brothers. The story of how the ordinary Quetzalcoatl became one of the heavenly brothers goes as followed.

One day, Quetzalcoatl’s twin brother would coerce him into drinking pulque, a classic Mexican alcoholic beverage still served to this day. While drunk, Quetzalcoatl seduced his sister, a celibate priestess. Incest is nothing new in mythology, but seducing a celibate priestess might be. Quetzalcoatl wasn’t all that happy with it, however.

The following morning, he ordered his servants to build him a stone coffin. He would submerge himself in a highly flammable substance and set himself on fire, granting himself a place amongst the stars.

From here, he would be seen as the morning star, while his twin brother would be seen as the evening star; planet Venus. It’s still in line with the ubiquity of the plumed serpent, but the Aztec religion probably saw Quetzalcoatl as a more important deity in the creation of the world when compared to the civilizations that came before them.

Quetzalcoatl as a Priest and a Prophet

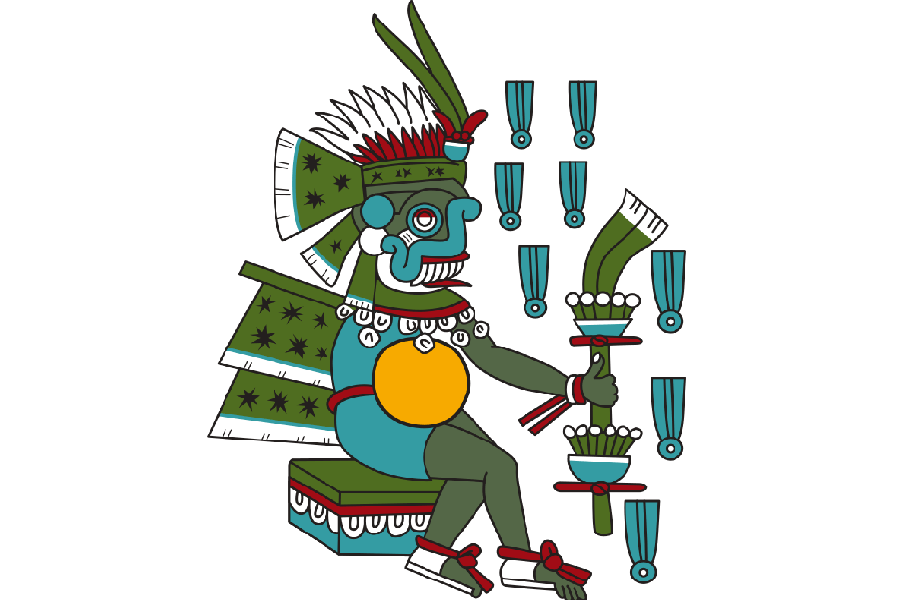

The importance of Quetzalcoatl in the Aztec civilization is, too, emphasized by his relationship with the priests of the empire. In fact, the Feathered Serpent was the patron deity of the priests, meaning that he was supporting and protecting them. Quetzalcoatl became, in fact, the very title of the most important priests: the twin Aztec High Priests.

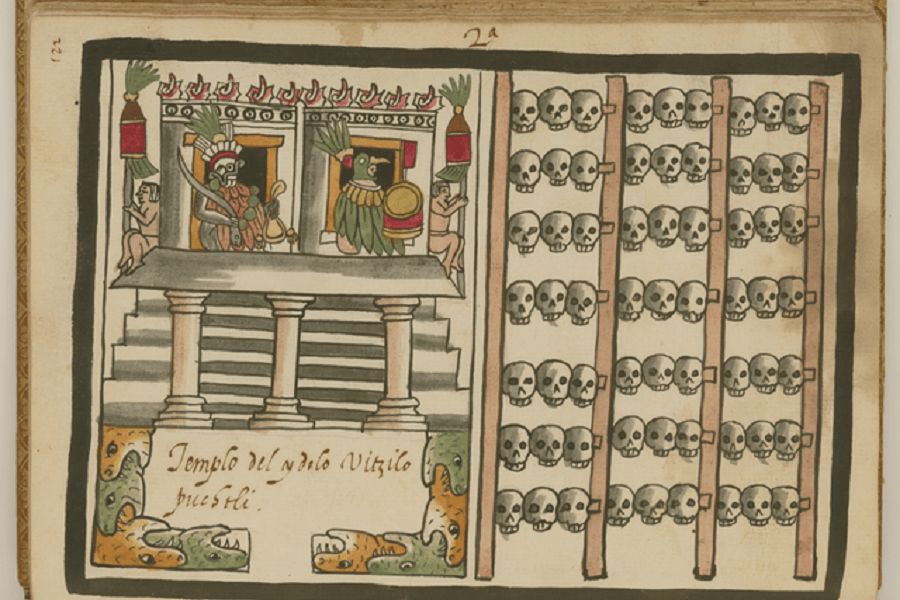

The two priests came to their position after living an exemplary life, with pure and compassionate hearts. They inhabited the top of the Great Pyramid dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. Tlaloc we already know. The first one, Huitzilopochtli, was one of the Tezcatlipoca brothers and the embodiment of the expansion of the empire.

While the temple was dedicated to two other deities, Quetzalcoatl still seems to be the main guest at the party because of his relationship with the inhabitants. The title of the twin Aztec high priests wasn’t just Quetzalcoatl. Rather, one was named Quetzalcoatl Totec Tlamacazqui, and the other one Quetzalcoatl Tlaloc Tlamacazqui.

Depictions of Quetzalcoatl

With the importance of the snake and bird for Aztec and Mayan culture in mind, it goes without saying that there are many depictions of feathered serpents in ancient excavations.

The earliest Aztec and classic Maya serpent iconography can be found in a six-tiered pyramid specifically dedicated to Quetzalcoatl. The temple can be found at Teotihuacan and was erected in the third century. It shows the first signs of a feathered serpent cult amongst ancient civilizations of the region.

Aztec and Maya Serpent Imagery of Quetzalcoatl

The Teotihuacan iconographical depictions are often interpreted as a version where Quetzalcoatl played the role of a fertility-related serpent deity. Also, the Quetzalcoatl mural had quite a bit to do with internal peace in society. This, it is believed, explains why he was looking ‘inwards’ to the city.

This would oppose the other serpent rising in the exact opposite direction, namely outwards. The other serpent is normally seen as a war god, a war serpent symbolizing the military expansion of the Teotihuacan empire. Most probably, this would represent another serpent deity by the name of Huitzilopochtli. Indeed, the same as the one from the Great Pyramid.

Other than Teotihuacán, large worship places can be found in Xochicalco and Cacaxtla.

Quetzalcoatl’s Later Depictions

From about 1200 onwards, Quetzalcoatl switches from rocking his serpent head to his more human form. In these instances, he is often seen wearing a lot of jewelry and some form of a hat. One of the jewels he is depicted with is the wind jewel, affirming his status as a wind god.

To this day, new depictions of the creator deity can be found in Mexico. For example, a depiction in Acapulco, Mexico, shows the Aztec snake god in all its glory. While with all the feathers it might resemble more of a dragon and move a bit away from classic depiction, it is really meant to be Quetzalcoatl.

Quetzalcoatl After the Spanish Conquest

The colonization of Mesoamerica, or rather Abya Yala, has severely impacted the area where Quetzalcoatl was worshiped. Where once feathered snakes were worshiped all over, after the Spanish conquest the locals were forced into worshiping Jesus Christ.

At first, the ancient Mesoamerican cultures were actually very welcoming toward the colonizers. Mainly because they thought one of them was the reincarnation of the beloved god discussed in this article.

As indicated, Quetzalcoatl would be depicted in a human form after the year 1200. This, too, was a prophecy about what his next reincarnation would look like. The invaders looked an awful lot like these late depictions.

Quetzalcoatl-Cortés Connection

Whether Quetzalcoatl would return was out of the question. His form of reincarnation, more specifically, would be that of a white person with a long beard. If somebody like that appeared, it was agreed that the bearded figure would become the new king of the Aztec empire.

It was not just a populist idea that gained interest in Aztec society. In fact, the then-current king himself, Moteuhzoma II, prophesied the return of Quetzalcoatl as a white-bearded person even if it would mean that he’d have to give up his place on the throne.

Hernán Cortés, perhaps the most notorious colonizer, is often identified as this very reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl. However, later sources uncover that already a year before him a similar figure dwelled in the lands of the Aztec territory. He wouldn’t become the new Aztec ruler, however. Nor would he be seen as the reincarnation of the Feathered Serpent god.

Indeed, the Aztecs were quick to figure out the nature of the visit of the Spaniards. This didn’t help a lot to overcome their cruel intentions, however. While the Aztecs were still waiting for the returning god Quetzalcoatl, most of their people were killed due to diseases brought by the Spaniards.

After only a couple of years, the Aztec empire ended due to a combination of foreign diseases and diplomacy. This, too, meant the end of the god Quetzalcoatl.