A cool spring breeze whispers through the tall trees. The waves of the Mississippi River lap lazily against the bow of the boat — the one you helped to design.

There are no maps to guide you and your party, for what lies ahead. It is land unknown and should you continue deeper in, that will only become more true.

There is the sudden sound of oars splashing as one of the men fights against the current, helping to move the heavily laden craft further upstream. Months of planning, training, and preparation have gotten you to this point. And now the journey is underway.

In the quiet — only broken by the rhythmic thrum of the oars — the mind begins to wander. Flickers of doubt creep in. Is there enough of the correct supplies packed to see this mission through? Were the right men chosen to help achieve this goal?

Your feet rest solidly upon the deck of the boat. The last remnants of civilization are disappearing behind you and all that separates you from your goal, the Pacific Ocean, is the wide open river… and thousands of miles of uncharted land.

There may be no maps right now, but when you return to St Louis — if you return — anyone who makes the journey after you will benefit from what you are about to accomplish.

If you don’t return, nobody is going to come looking for you. Most Americans may never even know who you were or what you gave your life to accomplish.

⬖

This is how the voyage of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, along with a small group of volunteers also known as “The Corps of Discovery” began.

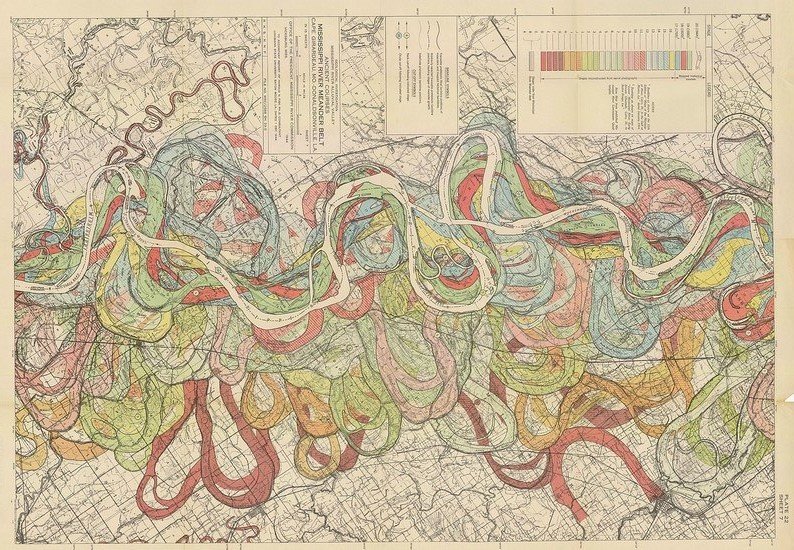

They had their objective — cross North America and reach the Pacific Ocean — and a best guess on how to accomplish it — follow the Mississippi River north from New Orleans or St. Louis and then chart navigable rivers westward — but the rest was unknown.

There was the possibility of encountering unknown diseases. Stumbling across indigenous tribes that were equally likely to be hostile or friendly. Getting lost in the expansive uncharted wilderness. Starvation. Exposure.

Lewis and Clark planned and equipped the Corps to the best of their ability, but the only certainty was that there was no guarantee of success.

Despite these dangers, Lewis, Clark, and the men following them pushed on. They wrote a new chapter in the history of American exploration, opening the door to westward expansion.

Table of Contents

What Was the Lewis and Clark Expedition?

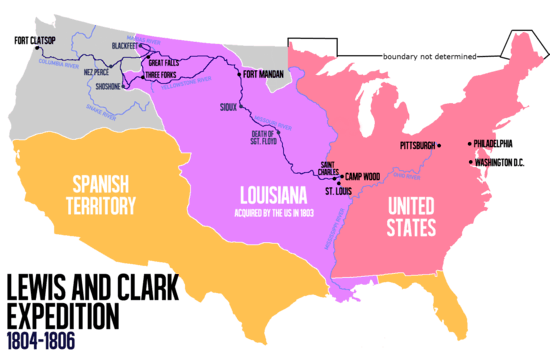

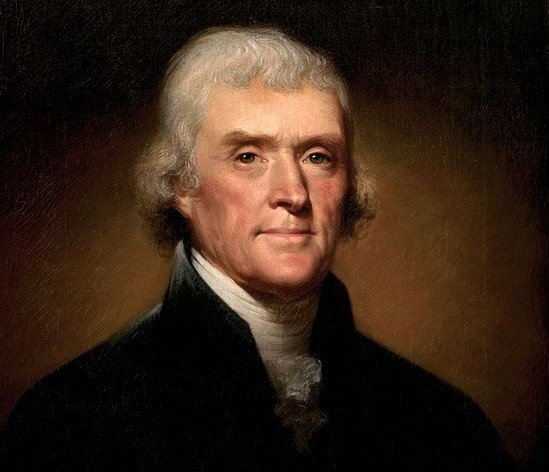

What Lewis and Clark set out to do was find and chart out a water route that could connect the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. It was commissioned by then-president, Thomas Jefferson, and was technically a military mission. Sounds simple enough.

The expedition left St. Louis in 1804 and returned in 1806, after having made contact with countless Native American tribes, documenting hundreds of plant and animal species, and mapping the way to the Pacific — although they found no water route that took them all the way there, as was their original intention.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

Although the mission sounds straightforward, there were no detailed maps that could possibly help them in understanding the challenges they might face during such a task.

There was sparse and undetailed information available regarding the enormous plains that lie ahead and no knowledge or expectation of the vast range of the Rocky Mountains even farther west.

Imagine that — these men set out across the country before people knew that the Rockies existed. Talk about uncharted territory.

Even so, two men — Meriwether Lewis and William Clark — were chosen based on their experience and, in the case of Lewis, their personal connection to President Thomas Jefferson. They were tasked to lead a small band of men into the unknown and return to enlighten people in the already settled eastern states and territories to what possibilities lay in the West.

Their responsibilities included not only charting out a new trade route, but also to gather as much information as they possibly could about the land, plants, animals, and indigenous peoples present.

A tall task, to say the least.

Who Were Lewis and Clark?

Meriwether Lewis was born in Virginia in 1774, but at the age of five his father passed away and he moved with his family to Georgia. He spent the next several years absorbing all that he could about nature and the great outdoors, becoming a skilled hunter and extremely knowledgeable. Much of this came to an end at the age of thirteen, when he was sent back to Virginia to get a proper education.

He apparently applied himself as much to his formal education as he had to his natural upbringing, as he graduated at the age of nineteen. Shortly thereafter, he enrolled in the local militia and two years later joined the official United States Army, receiving a commission as an officer.

He gained rank over the next couple of years and served, at one point, under the command of a man named William Clark.

As fate would have it, just after leaving the army in 1801, he was asked to become the secretary of a former Virginia associate — the newly elected president, Thomas Jefferson. The two men got to know each other very well and when President Jefferson needed someone he could trust to lead an important expedition, he asked Meriwether Lewis to take command.

William Clark was four years older than Lewis, having been born in Virginia in 1770. He was raised by a rural and agricultural slave-holding family that profited from maintaining several estates. Unlike Lewis, Clark never received a formal education, but loved to read and was, for the most part, self-educated. In 1785, the Clark family relocated to a plantation in Kentucky.

In 1789, at the age of nineteen, Clark joined a local militia that was tasked with pushing back the Native American tribes that desired to maintain their ancestral homelands near the Ohio River.

A year later, Clark left the Kentucky militia to join the Indiana militia, where he received a commission as an officer. He then left this militia to join another military organization known as the Legion of the United States, where he again received an officer’s commission. When he was twenty-six years old, he left military service to return to his family’s plantation.

That service must have been somewhat remarkable, though, as, even after having been out of the militias for seven years, he was quickly chosen by Meriwether Lewis to be second in command of the newly forming expedition into the uncharted West.

Their Commission

President Jefferson hoped to know much more about the new territory the United States had just acquired from France, during the Louisiana Purchase.

He tasked Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to chart a suitable route that crossed through the lands west of the Mississippi River and ended in the Pacific Ocean, to open the area for future expansion and settlement. It would be their responsibility to not only explore this strange new land, but to map it out as accurately as they could.

If possible, they also hoped to make peaceful friendships and trading relationships with any native tribes they may encounter along the way. And there was also a scientific side to the expedition — in addition to mapping their route, the explorers were responsible for recording natural resources, as well as any plant and animal species they encountered.

This included a particular interest of the president’s, to do with his passion for paleontology — the search for creatures he still believed to exist (but were actually long extinct), such as the mastodon and giant ground sloth.

This journey was not only exploratory, however. Other nations still held interest in the undiscovered country, and borders were loosely defined and agreed upon. Having an American expedition cross the land would help to establish an official presence of the United States in the area.

Preparations

Lewis and Clark started by establishing a special unit within the United States Army called the Corps of Discovery, and the latter was tasked with finding the best men for the almost unimaginable job ahead.

This would not be easy to accomplish. The men chosen would have to be willing to volunteer for an expedition into an unknown land with no tangible conclusion planned in advance, understanding the hardships and potential deprivations inherent in such an operation. They would also need to know how to live off the land and handle firearms for both hunting and defense.

These same men would also have to be the roughest, toughest type of adventurers available, but also amicable, dependable, and willing enough to take orders that most people would never be able to fulfill.

In the remote land ahead of them, loyalty was paramount. There would most certainly be unforeseen situations to arise that required quick action without time for discussion. The young democracy in the newly created United States was a wonderful institution, but the Corps was a military operation and its survival depended on it running like one.

Therefore, Clark carefully chose his men among the active and well-trained soldiers in the United States military; tried and true veterans of the Indian Wars and the American Revolution.

And with their training and preparations as complete as they could be, with their party standing at 33 men strong, the only sure date was May 14, 1804: the start of their expedition.

Lewis and Clarke Timeline

The full journey is covered in detail below, but here’s a brief overview of the timeline of the Lewis and Clark expedition

1803 – Wheels in Motion

January 18, 1803 – President Thomas Jefferson requests $2,500 from Congress to explore the Missouri River. Congress approves the funding on February 28th.

July 4, 1803 – The United States completes its purchase of the 820,000 square miles west of the Appalachian Mountains from France for $15,000,000. This is known as the Louisiana Purchase.

August 31, 1803 – Lewis and 11 of his men paddle their newly constructed 55 foot keelboat down the Ohio River on its maiden voyage.

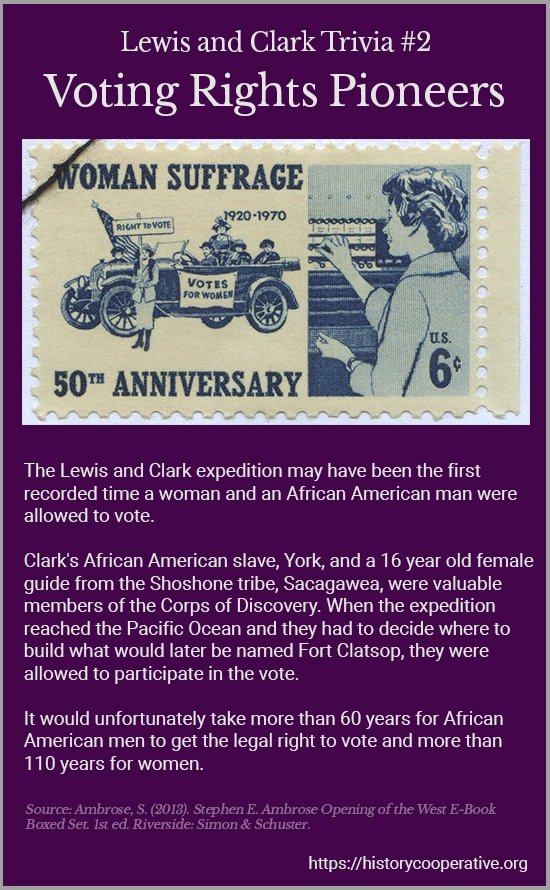

October 14, 1803 – Lewis and his 11 men are joined in Clarksville by William Clark, his African-American slave York, and 9 men from Kentucky

December 8, 1803 – Lewis and Clark setup camp for the winter in St. Louis. This allows them to recruit and train more soldiers as well as stock up on supplies

1804 – The Expedition is Underway

May 14, 1804 – Lewis and Clark depart Camp Dubois (Camp Wood) and launch their 55 foot keelboat into the Missouri River to begin their journey. Their boat is followed by two smaller pirogues laden with additional supplies and support crew.

August 3, 1804 – Lewis and Clark hold their first council with Native Americans – a group of Missouri and Oto chiefs. The council is held near the present-day city of Council Bluffs, Iowa.

August 20, 1804 – The first member of the party dies only three months after setting sail. Sergeant Charles Floyd suffers a burst appendix and is unable to be saved. He’s buried near present-day Sioux City, Iowa. He is the only member of the party to not survive the journey.

September 25, 1804 – The Expedition encounter their first major obstacle when a band of Lakota Sioux demand one of their boats before allowing them to proceed any further. This situation is diffused with gifts of medals, military coats, hats, and tobacco.

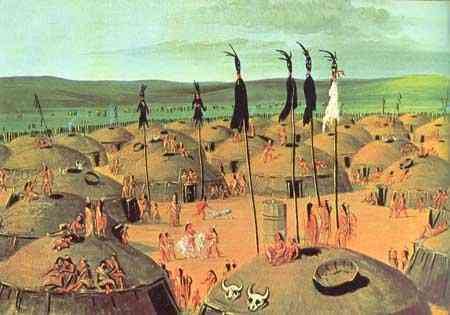

October 26, 1804 – The Expedition discovers the first large Native American village of their journey – the earth-lodge settlements of the Mandan and Hidatsas tribes.

November 2, 1804 – Construction begins on Fort Mandan on a site across the Missouri River from the Native American villages

November 5, 1804 – A French-Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife Sacagawea, who have been living amongst the Hidatsas, are hired as interpreters.

December 24, 1804 – Construction of Fort Mandan is complete and the Corps take refuge for the winter.

1805 – Deeper into the Unknown

February 11, 1805 – The youngest member of the party is added when Sacagawea gives birth to Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. He’s nicknamed “Pompy” by Clark.

April 7, 1805 – The Corps continue the journey from Fort Mandan up the Yellowstone River and down the Marias River in 6 canoes and the 2 pirogues.

June 3, 1805 – They reach the mouth of the Marias River and reach an unexpected fork. Unsure of which direction is the Missouri River, they make camp and scouting parties are sent down each branch.

June 13, 1805 – Lewis and his scouting party sight the Great Falls of Missouri, confirming the correct direction to continue the expedition

June 21, 1805 – Preparations are made to complete an 18.4 mile portage around the Great Falls, with the journey taking until July 2.

August 13, 1805 – Lewis crosses the Continental Divide and meets Cameahwait, the leader of the Shoshone Indians and returns with him across Lemhi Pass to establish Camp Fortunate to hold negotiations

August 17, 1805 – Lewis and Clark successfully negotiate the purchase of 29 horses in return for uniforms, rifles, powder, balls, and a pistol after Sacagawea reveals that Cameahwait is her brother. They will be guided over the Rocky Mountains on these horses by a Shoshone guide named Old Toby.

September 13, 1805 – The journey across the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass and Bitterroot Mountains depleted their already meager rations and, starving, the Corps were forced to eat horses and candles

October 6, 1805 – Lewis and Clark meet the Nez Perce Indians and exchange their remaining horses for 5 dugout canoes to continue their journey down the Clearwater River, Snake River, and Columbia River to the ocean.

November 15, 1805 – The Corps finally reach the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Columbia River and decide to camp on the south side of the Columbia River

November 17, 1805 – The construction of Fort Clatsop begins and is completed December 8. This is the winter home for the Expedition.

1806 – The Voyage Home

March 22, 1806 – The Corps leave Fort Clatsop to begin their journey home

May 3, 1806 – They arrive back with the Nez Perce tribe but are unable to follow the Lolo Trial over the Bitterroot Mountains due to snow still remaining in the mountains. They establish Camp Chopunnish to wait out the snow.

June 10, 1806 – The Expedition is led on 17 horses by 5 Nez Perce guides to Travellers Rest via Lolo Creek, a route that was some 300-miles shorter than their westward path .

July 3, 1806 – The Expedition is split into two groups with Lewis taking his group up the Blackfoot River and Clark leading his through Three Forks (Jefferson River, The Gallatin River, and the Madison River) and up the Bitterroot River.

August 12, 1806 – After exploring different river systems, the two parties reunite on the Missouri River near present-day North Dakota.

August 14, 1806 – The reach Mandan Villiage and Charbonneau and Sacagawea decide to remain.

September 23, 1806 – The Corps arrive back in St. Louis, completing their journey in two years, four months, and ten days.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition in Detail

The trials and tribulations of a two and a half year journey through uncharted and unexplored territory cannot be described adequately in a short point-by-point form.

Here is a comprehensive breakdown of their challenges, discoveries, and lessons:

The Journey Begins in St. Louis

With motors having yet to be invented, the boats belonging to the Corps of Discovery ran purely on man-power, and the trip upstream — against the strong torrents of the Missouri River — was slow going.

The keelboat that Lewis had designed was an impressive craft that was aided by sail, but even so, the men had to rely on paddles and the use of poles to push their way northward.

The Missouri river, even today, is known for its uncompromising currents and hidden sandbars. A few hundred years ago, traveling by small boats that were loaded down with men, enough food, equipment, and the firearms deemed necessary for the long voyage would have been difficult enough to maneuver traveling downstream; the Corps had persisted north, fighting all the way against the river.

This task alone took a great deal of strength and perseverance. The progress was slow; it took the Corps twenty-one days to reach the last known White settlement, a very small village named La Charrette, along the Missouri River.

Beyond this point, it was uncertain whether or not they would encounter another English-speaking person.

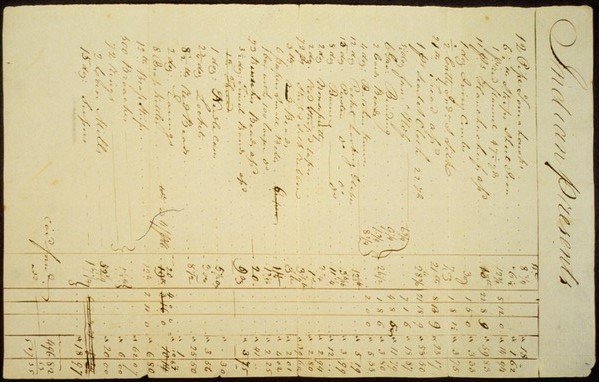

The men on the expedition were made aware, long before the journey began, that part of their responsibilities was going to be that of establishing relations with any Native American tribes they came across. In preparation for these inevitable encounters, packed with them were many gifts, including special coins called “Indian Peace Medals” that were minted with the likeness of President Jefferson and included a message of peace.

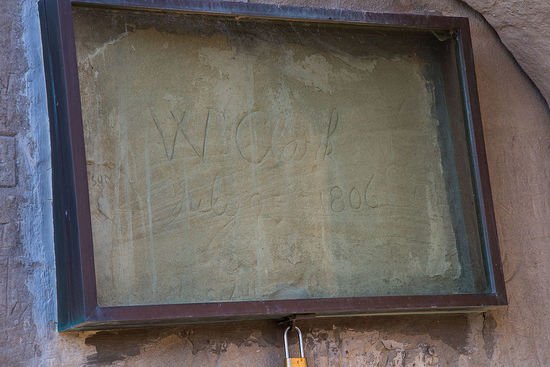

Cliff / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

And, just in case these items were not enough to impress those they met, the Corps was equipped with some unique and powerful weaponry.

Each man was equipped with the standard issue military flintlock rifle, but they also carried with them a number of prototype “Kentucky Rifles” — a type of long-gun that fired a .54 caliber lead bullet — as well as a compressed air-fired rifle, known as the “Isaiah Lukens Air Rifle”; one of the more interesting weapons they possessed. The keelboat, on top of carrying additional pistols and sporting rifles, was also equipped with a small cannon that could fire a lethal 1.5 inch projectile.

A lot of firepower for a peaceful mission of exploration, but defense was an important aspect to seeing their quest to fruition. Though, Lewis and Clark hoped that these weapons could primarily be used to impress the tribes they encountered, handling the weapons to avoid conflict instead of handling them for their intended purpose.

Early Challenges

On August 20th, after months of travel, the Corps reached an area now known as Council Bluffs in Iowa. It was on this day that tragedy struck — one of their men, Sergeant Charles Floyd, was suddenly overcome and fell violently ill, dying from what is thought to be a ruptured appendix.

But this wasn’t their first loss in manpower. Only a few days before, one of their party, Moses Reed had deserted and turned to trek back to St. Louis. And to add insult to injury, in doing so — after lying about his intentions and abandoning his men — he stole one of the company’s rifles along with some gunpowder.

William Clark sent a man by the name of George Drouillard back to St. Louis to retrieve him, as a matter of military discipline that was recorded in their official expedition log. The order was carried out and, soon, both men returned — only days before the death of Floyd.

As punishment, Reed was ordered to “run the gauntlet” four times. This meant passing through a double line of all other active Corps members, who were each ordered to strike him with clubs or even some small bladed weapons as he passed.

With the number of men in the company, it is likely that Reed would have received more than 500 lashes before being officially discharged from the expedition. This may seem a harsh punishment, but during this time, the typical punishment for Reed’s actions would have been death.

Although the incidents of Reed’s desertion and Floyd’s death occurred within only days of each other, the real troubles had yet to begin.

For the next month, each new day brought with it exciting discoveries of unrecorded plant and animal species, but as the end of September drew near, instead of encountering new flora and fauna, the expedition encountered a inhospitable tribe of the Sioux Nation — the Lakota — who demanded to keep one of the Corps’ boats as payment to continue their journey up the river.

The following month, in October, the party suffered another loss and was once again reduced in number as member Private John Newman was tried for insubordination and subsequently relieved of his duty.

He must have had an interesting time, during his journey alone back to civilization.

The First Winter

By the end of October, the expedition was well aware that winter was fast approaching and that they would need to establish quarters to wait out the harsh, freezing temperatures. They encountered the Mandan tribe near present-day Bismark, North Dakota, and marvelled at their earthen-log structures.

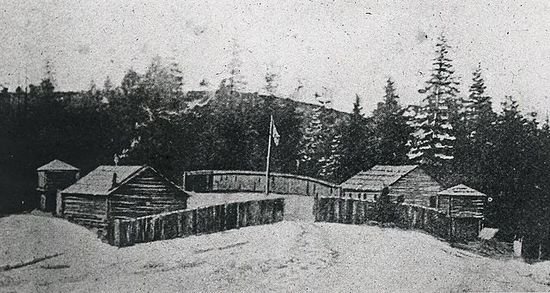

Received in peace, the Corps was allowed to make winter quarters across the river from the village, and build their own structures. They dubbed the encampment “Fort Mandan” and spent the next few months exploring and learning about the surrounding area from their newfound allies

Perhaps the presence of an English speaking man named Rene Jessaume, who had been living with the Mandan people for many years and could serve as an interpreter, made the experience of living next to the tribe easier.

It was during this time that they also encountered another friendly group of Native Americans, known as the Hidatsa. Within this tribe was a Frenchman named Toussaint Charbonneau — and he wasn’t a solitary man. He lived with his two wives, who came from the Shoshone Nation.

Women by the names of Sacagawea and Little Otter.

Spring, 1805

The spring thaw arrived in April and the Corps of Discovery once again ventured off, heading towards the Yellowstone River. But the number of the company had grown — Toussaint and Sacagawea, who had just given birth to a baby boy only two months earlier, joined the mission.

Eager to have local guides as well as someone to help communicate so as to build friendly relations with any Native American tribes they encountered, Lewis and Clarke were likely very happy with the additions to their party.

Having survived nearly a year — and the first winter — into their journey, the men of the expedition were confident in their abilities to survive their exploration of the frontier. But as is probable to happen after extended periods of success, the Corps of Discovery perhaps happened to be a little too confident.

A sudden and strong storm blew up as they traveled along the Yellowstone River, and the expedition — rather than seek shelter — chose to continue moving forward, confident they had the skills to navigate the bad weather.

This decision was nearly catastrophic. A sudden wave dumped one of their canoes over, and many of their valuable and irreplaceable supplies, including all of the Corps’ journals, found themselves sinking with the boat.

Whatever happened next isn’t recorded in detail, but somehow the boat and supplies were recovered. In his personal journal, William Clark gave credit to Sacagawea for quickly rescuing the items from being lost.

This close call may be partially responsible for the precautions the Corps later took throughout the rest of their journey; showing that the real threat they had been facing was their own overconfidence.

The men began storing a few morsels of essential supplies, hidden in various places along their route, as they entered more difficult and perhaps more treacherous terrain. They hoped this would help to provide some measure of safety and security on their journey home, equipping them with any supplies necessary for their survival.

After the dramatic events of the storm, they continued. It was slow going, and as they approached the heavier rapids along the mountain rivers, they decided it was time to try and assemble one of their pre-planned projects — that of an iron boat.

As if the journey wasn’t already challenging to begin with, the entire voyage, they had been carrying with them an assortment of heavy sections of iron, and now was the time to put them to use.

These cumbersome parts were designed to build a rigid boat that could endure the danger of the raging rapids the Corps were soon to encounter.

And it probably would have been a great solution, had it worked.

Unfortunately, everything didn’t quite fit together as it was designed to. After nearly two weeks of work to assemble the craft, and after only a single day of use, it was determined that the iron boat was a leaking mess and not safe for the journey, before it was then disassembled and buried.

Making Friends

As the old saying goes, “It’s better to be lucky than good.”

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, despite its crew possessing a large combined knowledge base and skillset, was in need of some good fortune.

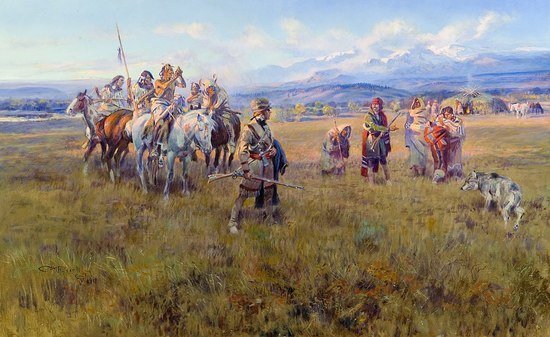

They struck upon just that when they arrived in the territory of the Shoshone Indian Tribe. Traveling through a wilderness as vast as the one they found themselves in, the chances of encountering other people were rather low to begin with, but there, in the middle of nowhere, they stumbled across none other than Sacagawea’s brother.

The fact that Sacagawea had joined their number only to encounter her own brother on the frontier seems an act of tremendous fortune, but it may not have been only luck — where the village was located was along a river (a reasonable place to settle), and it’s likely that Sacagewea led them there on purpose.

Regardless of how it came to be, meeting the tribe and being able to establish peaceful friendship with them was a great relief from the series of unfortunate events that the Corps of Discovery had endured.

The Shoshone were wonderful horsemen, and, seeing an opportunity, Lewis and Clark reached an agreement with them to trade some of their supplies for a number of their horses. These animals, the expedition thought, would make their journey forward much more amenable.

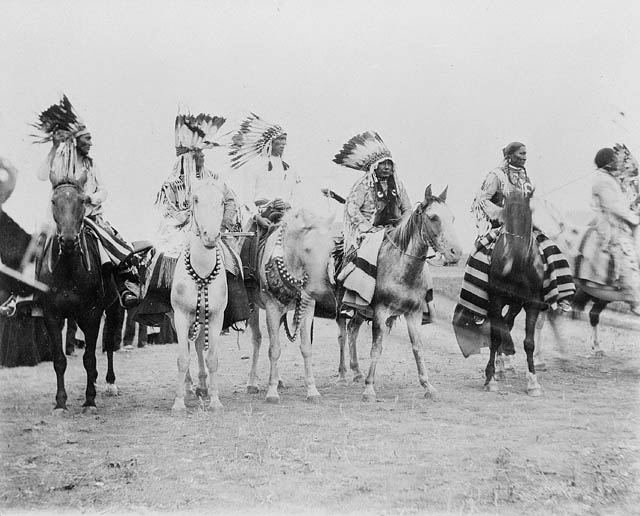

c1912

Ahead of them lay the Rocky Mountains, a terrain the party had very little knowledge of, and if not for meeting the Shoshone, the outcome of their journey across them may have ended very differently.

Summer, 1805

The further the Corps journeyed west, the more the land sloped upward, bringing with it cooler temperatures.

Neither Meriwether Lewis nor William Clark expected the Rocky mountain range to be as vast or as challenging to pass as it had revealed itself to be. And their trek was about to become an even more difficult struggle — between man, terrain, and unpredictable weather.

Treacherous to traverse through, with loose rock and dangerous storms that arrive with little notice; no sources of heat, and game for hunting becoming very scarce above the tree-line, mountains have been a source of wonder and fear to people for thousands of years.

For Lewis and Clark, with no maps as a guide — tasked with being the first to create them — they had no idea how steep and dangerous the land ahead of them would be, or if they were walking into a dead end marked by surrounding insurmountable cliffs.

Had they been forced to try and make this crossing on foot, the expedition may have been lost to history. But, thanks to the agreeable nature of the Shoshone people and their willingness to trade away several valuable horses, the Corps stood at least a slightly better chance of surviving the harsh geography and weather that lay ahead.

Plus, besides being beasts of burden, the horses served the expedition well in a land of little sustenance as a source of emergency nourishment for a starving group of explorers. Wild game and other foods were relatively scarce in the higher altitudes. Without those horses, the bones of the Corps of Discovery could have ended up hidden and buried out in the wilderness.

But that legacy was not what was left behind, and it is most likely due to the graciousness of the Shoshone Tribe.

The sheer amount of relief felt by each member of the expedition can be imagined as they witnessed — after weeks of exhausting travel — the mountain terrain open up into not only the majestic vistas from the western side of the Rockies, but also the view of a downward slope winding into forests below.

The return of that tree-line offered hope, as once again there would be wood for warmth and cooking, and game to hunt and eat.

With months of hardship and deprivation behind them, the comparably hospitable landscape of their descent was welcomed.

Fall, 1805

As October of 1805 rolled around and the party descended the western slope of the Bitterroot Mountains (near the borders of present-day Oregon and Washington state), they met with members of the Nez Perce tribe. The remaining horses were traded to over, and canoes were carved from the large trees that marked the landscape.

This put the expedition back on the water again, and with the current now flowing in the direction they were traveling, the going was much easier. Over the next three weeks, the expedition navigated the fast-flowing waters of the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia Rivers.

It was during the first week of November that their eyes finally took in the rolling blue waves of the Pacific Ocean.

The joy that filled their hearts at finally seeing the coastline for the very first time, after fighting tooth and nail against the elements for more than a year, is unimaginable. To have spent so long away from civilization, the sight had to bring many emotions to the surface.

The victory of reaching the ocean was tempered a bit by the reality that they had only reached the half-way point; they still had to turn around and make the return journey. The mountains loomed, just as they had a few weeks before.

Wintering Along the Pacific Coast

Now armed with the experience and knowledge of the area they would be returning through, the Corps of Discovery made the wise decision to spend the winter next to the Pacific, rather than head back into the Rocky Mountains ill-prepared.

They established a camp at the junction of the Columbia River and the ocean, and, during this short stay, the company set about preparations for the return trip — hunting for food saves and much needed clothing materials.

In fact, during their winter stay, the Corps spent time crafting up to 338 pairs of mocassins — a type of soft leather shoe. Footwear was of the utmost importance, especially in the face of crossing the snowy mountain terrain once again.

The Journey Home

The company departed for home in March of 1806, acquiring a suitable number of horses from the Nez Perce tribe and setting out, back over the mountains.

The months passed, and, in July, the group decided to take a different approach on their return trip by splitting into two groups. Why they did this isn’t totally clear, but it’s probable that they wanted to take advantage of their still strong numbers, covering more area by splitting up.

Navigation and survival was a strength among these men; the entire Corps met back up in August. Not only were they able to rejoin ranks, they were also able to locate what was left of the supplies they had buried a year earlier, including their failed iron boat.

They arrived back in St. Louis on September 23, 1806 — minus Sacagawea, who chose to remain behind when they reached the Mandan village she had left a year earlier.

Their experiences included creating and maintaining peaceful relationships with around twenty-four individual Native American tribes, documenting the numerous plant and animal life they encountered, and recording a route from the eastern coast of the United States all the way to the Pacific Ocean, thousands of miles away.

It would be Lewis and Clark’s detailed maps that paved the way for generations of explorers to come; those that eventually settled and “conquered” the West.

The Expedition That May Have Never Been

Remember that little word “luck” that seemed to travel alongside the Corps of Discovery?

It turns out that, at the time of the expedition, the Spanish had become well established in the New Mexico Territory and they were not very pleased with the idea of this journey to the Pacific Ocean through disputed territories.

Determined to make sure it never happened, they sent out several large armed parties with the goal of capturing and imprisoning the entire Corps of Discovery.

But these military detachments apparently were not held by the same fortune as their American counterparts -— they never managed to come in contact with the explorers.

There were also other, actual encounters along the expedition’s travels that could have ended far differently and potentially changed the outcome of their entire mission.

Reports from trappers and others familiar with the land — before the journey — informed Lewis and Clark of several tribes that potentially posed a threat to the expedition, should they come across them.

One of these tribes — the Blackfoot — they did happen to stumble across in July, 1806. A successful trade was said to have been negotiated between them, but the next morning, a small group of Blackfoots attempted to steal the expedition’s horses. One of them turned towards William Clark aiming an old musket, but Clark managed to fire first, and shoot the man in the chest.

The rest of the Blackfoot fled and the party’s horses were retrieved. When it was over, the man who had been shot lay dead, as well as another who was stabbed during the altercation.

Understanding the danger they were in, the Corps quickly packed up their camp, leaving the area before any more violence erupted.

Another tribe, the Assiniboine, held a certain reputation for being hostile towards intruders. The expedition encountered many signs that the Assiniboine warriors were close, and went to great lengths to avoid any contact with them. At times, they would alter their course or halt the entire journey, sending out scouts to ensure their safety before continuing.

The Costs and the Rewards

In the end, the total cost of the expedition totalled about $38,000 (the equivalent of nearly a million US dollars, today). A fair sum in the opening years of the 1800’s, but probably nowhere near what such an undertaking would cost if this expedition were to take place in the 21st century.

In recognition of their accomplishments over the two and a half year long journey, and as a reward for their success, both Lewis and Clark were awarded 1,600 acres of land. The rest of the Corps received 320 acres each, and double pay for their efforts.

Why Did the Lewis and Clark Expedition Happen?

Early European settlers in America had spent much of the 17th and 18th centuries exploring the east coast from Maine to Florida. They established cities and states, but the more they moved westward, closer to the Appalachian Mountains, the fewer the settlements and the fewer the number of people there were.

The land west of this mountain range was, at the turn of the 19th century, the wild frontier.

The borders of many states may have extended as far west as the Mississippi River, but the population centers of the United States all trended towards the comfort and safety afforded by the Atlantic Ocean and its coastline. Here, there were ports frequented by ships that brought all manner of goods, materials, and news from the “civilized” European continent.

Some people were content with the land as they knew it, but there were others who had great ideas for what may lay beyond those mountains. And because there was so much unknown about the West, secondhand stories and outright rumors provided average Americans the opportunity to dream of a time when they could own their own land and experience true freedom.

The tales also inspired visionaries and wealth-seekers with plenty of resources to seek out a much greater future. Thoughts of overland and waterway trading routes that could reach the Pacific Ocean occupied the minds of many.

One such person was the third, and newly elected, President of the United States — Thomas Jefferson.

The Louisiana Purchase

At the time of Jefferson’s election, France was in the middle of a great war that was being led by a man by the name of Napoleon Bonaparte. On the American continent, Spain had traditionally controlled the area west of the Mississippi River that later became known as the “Louisiana Territory.”

After some negotiations with Spain, in part brought on by protests in the West — most notably the Whiskey Rebellion — the US managed to gain access to the Mississippi River and the lands to the west. This allowed goods to flow into and out of its far and remote borders, increasing trade opportunities and the ability for the US to expand.

However, soon after Jefferson’s election in 1800, word arrived in Washington D.C. that France had gained the official claim from Spain to this vast region due to its military successes in Europe. This acquisition by France brought a sudden and unexpected end to the friendly trade agreement between the United States and Spain.

Many businesses and traders already engaged in utilizing the Mississippi River for their livelihood began urging the country towards a war, or at the very least armed confrontations, with France to gain control of the territory. As far as these people were concerned, the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans must remain in the operational interest of the United States.

However, President Thomas Jefferson had no desire to go up against the well-supplied and expertly-trained French army. It was imperative to find a solution to this growing problem without becoming entangled in another bloody war, especially against the French, who had, only a few years prior, helped the United States gain victory over England during the American Revolution.

Jefferson also knew that France’s protracted war had exacted quite a toll on the country’s finances; Napoleon diverting a large portion of his fighting force to defend the newly-acquired North American territory might have likely appeared to be a tactical disadvantage.

All of this equated to an excellent opportunity for resolving this crisis diplomatically, and in a way that would favor both sides.

So, the president set his ambassadors into action to find some way of finding a peaceful solution to this potential conflict, and what followed was a rapid series of brilliant diplomatic decision making and immaculate timing.

Thomas Jefferson went into the process having authorized his ambassadors to offer up to $10,000,000 for the purchase of the territory. He had no idea if such an offer would find amicable reception in France, but he was willing to try.

In the end, Napoleon was surprisingly receptive to the offer, but he too was highly skilled at the art of negotiation to take it without some discourse on his end. Seizing upon the opportunity to rid himself of the distraction of a divided fighting force — as well as to get some much needed financing for his war — Napoleon settled on the final figure of $15,000,000.

The ambassadors agreed to the deal and, suddenly, the United States had doubled in size without a single shot being fired in anger.

It was soon after acquiring the territory that Jefferson commissioned an expedition to explore and map it, so that it could one day be organized and settled — which we now know as the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

How Did the Lewis and Clark Expedition Impact History?

The initial and lasting impacts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition are probably much more debated today than they were in the first few decades after the expedition arrived safely home.

Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny

For the United States, this expedition proved that such a journey was possible and ushered in a time of westward expansion, fueled by the idea of Manifest Destiny — the collective belief that it was the inevitable future of the United States to extend from “sea to shining sea,” or from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This movement inspired a great number of people to flock to the West.

These newcomers to the land were spurred on by reports of a great bounty to be had in both lumber and trapping. Money was to be made in the vast new territory and both companies and individuals alike set out to make their fortunes.

The great era of westward growth and expansion was a great economic boon to the United States of America. It seemed the abundant resources of the West were nearly inexhaustible

However, all of this new territory forced Americans to confront a key issue in its history: slavery. Specifically, they would have to decide if the territories added to the United States would permit human bondage or not, and the debates over this issue, fueled also by territorial gains from the Mexican-American War, dominated 19th century Antebellum America and culminated in the American Civil War.

But at the time, the success of Lewis and Clark’s Expedition helped to encourage the establishment of numerous trail and fort systems. These “highways to the frontier” brought an ever-increasing number of settlers westward, and this undoubtedly had a profound impact on economic growth in the United States, helping turn it into the nation it is today.

Displaced Natives

As the United States expanded throughout the 19th century, the Native Americans who called the lands home were displaced and this resulted in a profound change in the demographics of the North American continent.

Natives who weren’t killed by disease, or in wars waged by the expanding United States, were corralled and forced into reservations — where the land was poor and economic opportunities were few.

And this was after they had been promised opportunities in the US country, and after the United States Supreme Court had ruled that the removal of Native Americans was illegal.

This ruling — Worcester vs. Jackson (1830) — occurred during Andrew Jackson’s presidency (1828–1836), but the American leader, who is often revered as one of the nation’s most important and influential presidents, defied this decision made by the nation’s highest court and forced Native Americans off their land anyway.

This led to one of the greatest tragedies in American history — “The Trail of Tears” — in which hundreds of thousands of Native Americans died while being forced from their lands in Georgia and onto reservations in what is now Oklahoma.

Today, very few Native Americans remain, and those that do are either culturally repressed or suffering from the many challenges that come from life on a reservation; mainly that of poverty and substance abuse. Even as recently as 2016/2017, the US government was still unwilling to recognize Native American rights, ignoring their arguments and claims made against the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The way in which the United States government has treated Native Americans remains one of the great stains on the country’s story, on par with that of slavery, and this tragic history began when first contact was made with the native tribes of the West — both during and after the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Environmental Degradation

The collective view of the land acquired from the Louisiana Purchase as a well-spring of material and income generation was taken advantage of by many people with very closed minds. Little thought was given to any possible long-term impacts — such as the destruction of Native American tribes, soil degradation, and the depletion of wildlife — that sudden and rapid westward expansion would bring about.

And as the West grew, larger and more remote areas became safer for commercial exploration; mining and lumber companies entered the frontier, leaving behind a legacy of environmental destruction. With each passing year, old growth forests were completely erased from the hills and mountain sides. This devastation was coupled with careless blast and strip mining that resulted in massive erosion, water pollution, and habitat loss for local wildlife.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition in Context

Today, we can look backwards in time and think about the many events that took place after the US acquired the land from France and after Lewis and Clark explored it. We can wonder how things may be different, if more strategic and long-term planning had been considered.

It is easy to look at the American settlers as nothing more than greedy, racist, uncaring foes to both the land and the native people. But while it is true that there was no shortage of this as the West grew, it is also true that there were many honest, hard working individuals and families who just wanted an opportunity to support themselves.

There were many settlers who traded openly and honestly with their indigenous neighbors; a number of those indigenous people saw value in the lives of these newcomers and so tried to learn from them.

The story, as usual, is not as cut and dry as we might like.

History is in no way short of stories from around the globe of expanding populations overcoming the lives and traditions of the people they encountered as they grew. The expansion of the United States from the East coast to the West is another example of this phenomenon.

JERRYE AND ROY KLOTZ MD / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

The impacts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition can still be seen and felt today in the lives of millions of Americans, as well as in Native tribes that managed to survive the turbulent history their ancestors experienced after the Corps of Discovery paved the way for settlers. These challenges will continue to write upon the legacy of Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, the entire expedition, and President Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a greater America.

enjoyed it and learned a lot of information I had not known before. nice work.