William the Conqueror, also known as William I, was a Norman Duke who became King of England after defeating the English army in the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

William’s reign was marked by significant changes in the social, political, and economic structures of England. He introduced a feudal system of land ownership and centralized government, and he also commissioned the Domesday Book, a comprehensive survey of England’s land and property holdings, and much more.

Table of Contents

Who Was William the Conqueror?

William the Conqueror was England’s first Norman king, ascending to the throne in 1066 when he defeated the army of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. Ruling under the name William I, he held the throne for twenty-one years, until his death in 1087 at the age of 60.

But he was no mere placeholder – in the two decades he ruled England, he brought significant cultural, religious, and legal changes to the kingdom. And his rule had measurable and lasting impacts on the relationship between England and Continental Europe.

The Normans

William’s story actually begins well before his birth, with the Vikings. Raiders from Scandinavia came to the area later known as Normandy in the 9th Century CE and eventually began setting up permanent settlements on the coast, exploiting the weakness of the fractured Carolingian Empire, raiding inland as far as Paris and the Marne Valley.

In 911 CE Charles III, also known as Charles the Simple, entered into the Treaty of St Clair sur Epte with the Viking leader Rollo the Walker, ceding much of the territory then called Neustria as a buffer against future waves of Viking raiders. As the land of the so-called Northmen, or Normans, the area came to be called Normandy, and it would be expanded some 22 years later to the full area now recognized as Normandy in a deal between King Rudolph and Rollo’s son, William Longsword.

Was William a Viking?

To establish themselves more firmly in the region, the Viking settlers of Normandy married into the Frankish noble families adopted Frankish customs, and converted to Christianity. There were still pushes for a unique Norman identity – largely to accommodate new waves of settlers – but the overall trend was toward full assimilation.

William was born in 1028 as the 7th Duke of Normandy – though that title seems to have been used interchangeably with the more common Count or Prince. By that time, Normans had been intermarrying with Franks for over a century, and the Norse language was utterly extinct in the region.

The Normans still held onto some aspects of Viking heritages, though these were mostly symbolic (William did use Viking-style longships in his invasion, but this may have been more for their practical utility than for any cultural reasons). For the most part, however, while William was of Viking heritage – he was described as a tall, solidly-built man with reddish hair – in most other respects he would have been largely indistinguishable from any Frankish lord in Paris.

The Young Duke

William was the son of Robert I, called Robert the Magnificent, and his concubine, Herleve, who is also the likely mother of William’s younger sister, Adelaide. While his father remained unmarried, his mother would later marry a minor lord named Herluin de Conteville and bear two half-brothers for William, Odo and Robert.

Robert I set off on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1034, naming William his heir just before departing. Unfortunately, he would never return – he fell ill on the return trip and died in Nicea in 1035, leaving William as Duke of Normandy at the age of 8.

William would normally have been denied succession due to his illegitimacy. Fortunately, he had the support of his family – particularly his great-uncle Robert, Archbishop of Rouen, who also acted as William’s regent until his death in 1037.

Yet William was still branded with the moniker “William the Bastard,” and despite his family’s support, his illegitimacy – along with his youth – still left him in a very weak position. When Archbishop Robert died, it touched off a flurry of feuds and power struggles among the noble families of Normandy which threw the region into chaos.

The young Duke was passed between a number of guardians over the following years, most of whom were slain in apparent attempts to seize or kill William. Despite the support of the King Henry of France (who later knighted William when he was 15), William found himself facing numerous rebellions and challenges that would continue to some degree for almost 20 years after his regent’s death.

Family Feud

The key challenge to William came from his cousin, Guy of Burgundy, as Normandy’s general disarray coalesced into a focused rebellion against William in 1046. Citing a stronger claim to the Duchy as a legitimate heir of their grandfather, Richard II, Guy emerged as the head of a conspiracy against William that at first sought to seize him at Valognes, then met him in battle at the plain of Val-ès-Dunes, near modern-day Conteville.

Buttressed by the larger army of King Henry, William’s forces defeated the rebels, and Guy retreated with a remnant of his army to his castle at Brionne. William besieged the castle for the next three years, finally defeating Guy in 1049, at first allowing him to remain at court but ultimately exiling him the following year.

Securing Normandy

Shortly after Guy’s defeat, Geoffrey Martel occupied the French county of Maine, prompting William and King Henry to join together again to expel him – giving William control over much of the region in the process. Around this same time (though some sources put it as late as 1054), William married Matilda of Flanders – a strategically vital region of France now part of modern-day Belgium. Matilda, a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon House of Wessex, was also a granddaughter of the French King Robert the Pious, and as a result, held a higher status than her husband.

The marriage had supposedly been arranged in 1049 but had been forbidden by Pope Leo IX on the grounds of familial relation (Matilda was William’s third cousin once removed – a breach of the then-stringent rules that forbade marriage within seven degrees of relatedness). It finally went ahead about 1052, when William was 24 and Matilda 20, apparently without papal sanction.

King Henry saw William’s increasing territory and status as a threat to his own rule, and to reassert his dominion over Normandy, he partnered with Geoffrey Martel in 1052 in a war against his former ally. At the same time, William was beset by yet another internal rebellion, as some of the Norman lords were likewise eager to undercut William’s growing power.

Fortunately, the rebels and the invaders were never able to coordinate their efforts. Through a combination of skill and luck, William was able to both put down the rebellion and then face the dual invasion by Henry and Geoffrey’s armies, vanquishing them in the Battle of Mortemer in 1054.

That was not the end of the conflict, however. In 1057 Henry and Geoffrey invaded again, meeting defeat this time at the Battle of Varaville when their armies were split during a river crossing, leaving them vulnerable to William’s assault.

Both the king and Geoffrey would die in 1060. Just the year before, Pope Nicholas II had finally legitimized William’s marriage to his high-born wife with a papal dispensation, which – coupled with the death of his greatest opponents, left William finally in a secure position as Duke of Normandy.

The Fall of the House of Wessex

In 1013, the Viking king of Denmark Sweyn Forkbeard had seized the throne of England, deposing the Anglo-Saxon king Ethelred the Unready. Ethelred’s wife, Emma of Normandy, had fled to her homeland with her sons Edward and Alfred, with Ethelred following soon after.

Ethelred was able to return briefly when Sweyn died in early 1014, but Sweyn’s son Cnut invaded the following year. Ethelred died in 1016, and his son from a previous marriage, Edmund Ironside, successfully managed a stalemate with Cnut – but he died just seven months after his father, leaving Cnut as King of England.

READ MORE: In Search of Origins: Who Invented England and How?

Once again, Edward and Alfred went into exile in Normandy. This time, however, their mother stayed behind, marrying Cnut on the condition (as stated in 11th Century Encomium of Queen Emma) that he would name no heir except a son of hers – likely a way to not only retain her family’s status but protect her other sons as well – and later bearing him a son of his own, Harthacnut.

Family Ties

Emma was the daughter of Richard I of Normandy – the son of William Longsword and grandson of Rollo. When her sons returned to exile in Normandy, they stayed under the care of her brother, Richard II – William’s grandfather.

William’s father Robert had even attempted to invade England and restore Edward to the throne in 1034, but the effort failed. And when Cnut died the following year, the crown went instead to Edward’s half-brother Harthacnut.

Initially, Harthacnut stayed in Denmark while a half-brother, Harold Harefoot, ruled England as his regent. Edward and Alfred returned to England to visit their mother in 1036 – supposedly under Harthacnut’s protection, though Harold captured, tortured, and blinded Alfred, who died soon after, while Edward managed to slip back to Normandy.

In 1037, Harold usurped the throne from his half-brother, sending Emma fleeing once again – this time to Flanders. He ruled for three years until his death when Harthacnut returned and finally took the English throne.

King Edward

Three years later, the childless Harthacnut invited his half-brother Edward back to England and named him as his heir. When he died just two years later at the age of 24 from an apparent stroke, Edward became king, and the House of Wessex ruled once more.

At the time Edward took the throne, he’d spent most of his life – over twenty years – in Normandy. While he was Anglo-Saxon by blood, he was undoubtedly the product of a French upbringing.

This Norman influence did nothing to endear him to the powerful Earls with whom he had to contend. The influence of the House of Wessex had waned sharply during Danish rule, and Edward found himself in a prolonged political (and occasionally military) struggle to keep his power.

After over twenty years on the throne, Edward died, childless, at the age of 61. The last king of the House of Wessex, his death set off a struggle to determine England’s future.

The Contenders

Edward’s mother had been William’s great-aunt, and while the House of Wessex had largely withered, the Normandy side of Edward’s family was thriving. Coupled with Edward’s strong personal connection to Normandy, it’s not unreasonable to think he’d intended William to succeed him.

And William made that exact claim – that in 1051, Edward had designated him as heir to the throne. That was the same year Edward had sent his wife, Earl Godwin’s daughter, Edith, to a nunnery for failing to produce a child. It was also the year William supposedly visited Edward, according to the account for that year in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

But if Edward did use that visit to name William his heir, there is no mention of it. More to the point, Edward named someone else as his heir six years later in 1057 – a nephew called Edward the Exile, though he died the following year.

Edward didn’t name anyone else after his nephew died, so it’s at least possible that he had in fact named William, changed his mind when another descendant of Ethelred became available, and simply defaulted back to William when that didn’t work out. But whatever the case, William’s claim on the throne wasn’t the only one being made – there were a handful of other contenders, each with their own rationales for their succession.

Harold Godwinson

Edward’s brother-in-law, Harold had taken over as Earl of Wessex after his father died in 1053. The family’s power had grown significantly in the following years, as Harold’s brothers took over the earldoms of Northumbria, East Anglia, and Kent.

Edward had become more and more detached from the work of governing, leaving Harold in an increasingly powerful position. His only significant rival, his brother Tostig, Earl of Northumbria, had been beset by rebels and ultimately forced into exile – an outcome the king had actually sent Harold to help prevent, but the Earl of Wessex either couldn’t help his brother or chose not to, leaving Harold without peer.

Edward is said to have instructed Harold to look after the kingdom on his deathbed, but what he meant by that is unclear. Harold had by that time played a major role in running the government for quite a while, and Edward may simply have wanted him to continue to be a stabilizing force without necessarily offering him the crown – something he easily could have specified if it was what he intended.

Edgar Atheling

When Edward’s half-brother Edmund Ironside died, his sons Edward and Edmund were sent to Sweden by Cnut. Swedish King Olaf, a friend of Ethelred, had sent them on to safety in Kiev, from which they ultimately went to Hungary in about 1046.

Edward the Confessor had negotiated the return of his nephew, now called Edward the Exile, in 1056 and named him heir. Unfortunately, he died shortly thereafter but left a son – Edgar Atheling – who would have been about five or six at the time.

Edward never named the boy his heir nor gave him either titles or land, despite his bloodline. This suggests that Edward may have had reservations about putting such a young heir on the throne given his own difficulty dealing with the earls.

Harald Hardrada

Harthacnut had held the thrones of both England and Denmark, and around 1040 had negotiated a peace with King Magnus of Norway which declared that whichever of them died first would be succeeded by the other. When Harthacnut died in 1042, Magnus intended to invade England and claim the throne but died himself in 1047.

His successor in Norway, Harald Hardrada, considered himself to have inherited Magnus’ claim to the throne. He had additional encouragement from the exiled Tostig, brother of Harold Godwinson, who seems to have invited Harald to invade England to stop his half-brother Harold from taking the crown.

The Battle for the Throne

The witan, or king’s council, at least nominally selected the next king under Anglo-Saxon law (though how much they could overrule the last king’s wishes is questionable). Immediately after Edward’s death, they named Harold King. He would rule for about nine months as Harold II, prompting invasions by both William and Harald Hardrada.

Hardrada and Earl Tostig arrived first, landing in Yorkshire in September of 1066, and meeting up with Tostig’s Scottish ally, Malcolm III. After seizing Yorkshire, they headed south, expecting only light resistance.

But unbeknownst to them, Harold was already on the way and arrived just miles from their landing site the same day they captured York. His forces surprised the invaders at Stamford Bridge, and in the resulting battle the invading forces were routed, and Harald Hardrada and Tostig were both slain.

With what was left of the broken Danish forces fleeing back to Scandinavia, Harold turned his attention to the south. His army marched non-stop to meet William, who had crossed the channel with an army of some 11,000 infantry and cavalry and had now ensconced himself in East Sussex.

The forces met on October 14th near Hastings, with the Anglo-Saxons setting up a shield wall on Senlac Hill which managed to hold for most of the day until breaking formation to pursue some retreating Normans – a costly mistake since it exposed their lines to a devastating assault by William’s cavalry. Harold and two of his brothers fell during the fighting, but the now-leaderless English forces still held out until nightfall before finally being scattered, leaving William unopposed as he marched to London.

In the aftermath of Harold’s death, the witan debated naming Edgar Atheling as king, but support for that idea melted away as William crossed the Thames. Edgar and the other lords surrendered to William at Berkhamsted, just northwest of London.

William’s Reign

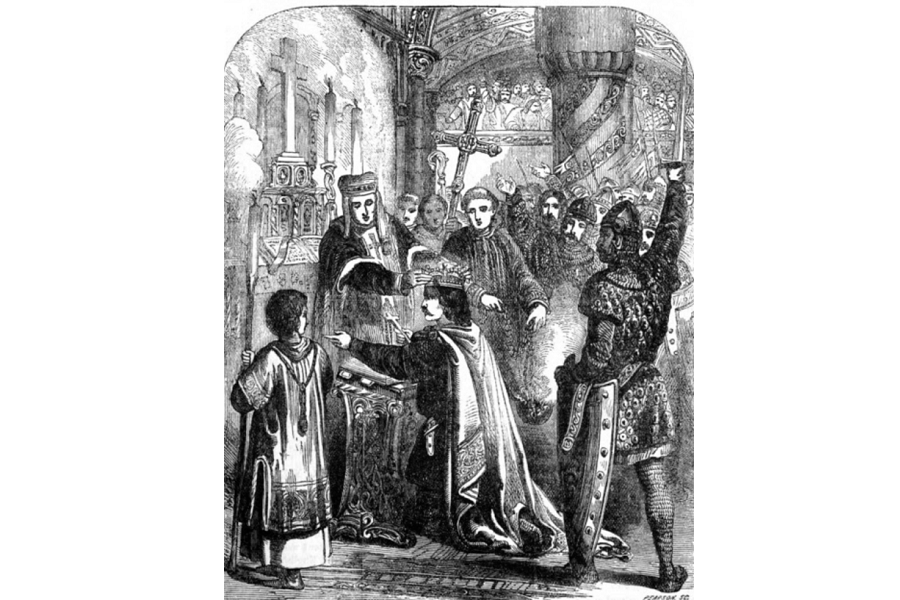

William’s coronation as William I – now known also as William the Conqueror – was held in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day of 1066, with the proceedings announced in both Old English and Norman French. Thus began the era of Norman domination of England – though continued threats to his position in Normandy meant William wouldn’t be present for much of it.

He returned to Normandy just a few months later, leaving his new acquisition in the hands of two loyal co-regents – William FitzOsbern and William’s own half-brother Odo, now Bishop of Bayeux (who likely also commissioned the famous Bayeux Tapestry depicting William’s conquest of England). His hold on England wouldn’t be secure for years due to various rebellions, and William made dozens of trips back and forth across the channel juggling the challenges of his two realms.

The Heavy Hand

The rebellions William faced in England came to a head in 1069. In the north, Mercia and Northumbria revolted in 1068, at about the same time that the sons of Harold Godwinson began making raids on the southwest.

The following year Edgar Atheling, the last surviving claimant to the throne, attacked and occupied York. William, who had returned to England briefly in 1067 to put down a revolt in Exeter, returned once more to march on York, though Edgar escaped and, in the fall of 1069 alongside Sweyn II of Denmark and a collection of rebellious lords, took York once again.

William again returned to retake York, then negotiated some sort of settlement with the Danes (likely a large payment) which sent them back to Scandinavia, and Edgar took refuge with Tostig’s old ally, Malcolm III, in Scotland. William then took drastic steps to pacify the north once and for all.

He invaded Mercia and Northumbria, destroying crops, burning churches, and leaving the region devastated for years to come depriving both rebels and Danish invaders of resources and support. William also dotted the landscape with castles – simple motte and bailey constructions with wooden palisades and towers on earthen mounds, later replaced by formidable stone fortresses – which he placed near cities, villages, strategic river crossings, and anywhere else they had defensive value.

A second rebellion, known as the Revolt of the Earls occurred in 1075. Led by the Earls of Hereford, Norfolk, and Northumbria, it quickly failed due to a lack of support from the Anglo-Saxon people and betrayal by the Earl of Northumbria, Waltheof, who revealed the plan to William’s allies.

William himself was not in England at the time – he had been in Normandy for two years at that point – but his men in England defeated the rebels quickly. It was the last significant revolt against William’s rule in England.

And the Reforms

But there was more to William’s rule than military action. He also made substantive changes to England’s political and religious landscape as well.

Much of the English aristocracy had died in the battles of the invasion, and William confiscated the lands of many more – especially the remaining relatives of Harold Godwinson and their supporters. He parceled out this land to his knights, Norman lords, and other allies – by the time of William’s death, the aristocracy was overwhelmingly Norman, with only a few estates still in English hands. But William didn’t just redistribute land – he changed the rules of land ownership as well.

Under the Anglo-Saxon system, nobles held land and provided a fyrd, similar to a militia, composed of freemen or mercenaries. Part-time soldiers usually provided their own equipment, and the fyrd was exclusively infantry – and while the king could call up a national army, the troops from different shires often struggled to coordinate their movements or operations.

By contrast, William introduced a true feudal system, in which the king owned everything, granting land to loyal lords and knights in return for swearing to provide a set number of troops for the king’s use – not farmers and other workers as in the fyrd, but a corps of trained, equipped soldiers – cavalry as well as infantry. He also introduced the concept of primogeniture, in which the eldest son inherited their father’s entire estate rather than have it divided among all the sons.

And as part of organizing land grants, William ordered the creation of the Book of Winchester, later known as the Domesday Book. Created between 1085 and 1086, it was a meticulous survey of English land holdings, including the tenant’s name, tax assessments of their land, and various details of properties and towns.

Religious Conversion

Deeply pious himself, William also enacted a number of ecclesiastical reforms. Most bishops and archbishops were replaced with Normans, and the church was reorganized into a stricter, more centralized hierarchy that brought it more in line with the European church.

He abolished the sale of ecclesiastical privileges, known as simony. And he replaced Anglo-Saxon cathedrals and abbeys with new Norman constructions, as well as rebuilt the simple wooden churches – common in parishes across England – with stone. The number of churches and monasteries grew significantly in this Norman construction boom, and the number of monks and nuns quadrupled.

William’s Legacy

In 1086, William left England for the last time. Just three years later, he would fall from his horse during a siege in the county of Vexin, for which he and French King Philip I contended. Said to have become quite heavy in later life, William succumbed to a combination of the heat and his injuries, and died on September 9th, 1087, at the age of 59.

But his impact on England lived on. French was the language of the elite in England for some three centuries after the Norman invasion, and Norman castles and monasteries still cover the English landscape, including the famous Tower of London.

William and the Normans introduced the Anglo-Saxon country to the concept of surnames, and imported Norman words like “beef,” “purchase,” and “noble.” They even successfully bred rabbits on the island for the first time. And the political and religious reforms he brought shaped the course of England for centuries to come.