Valkyries are powerful female mythical beings from Norse mythology. They were considered handmaidens of Odin, the All-Father and chief god in Norse mythology.

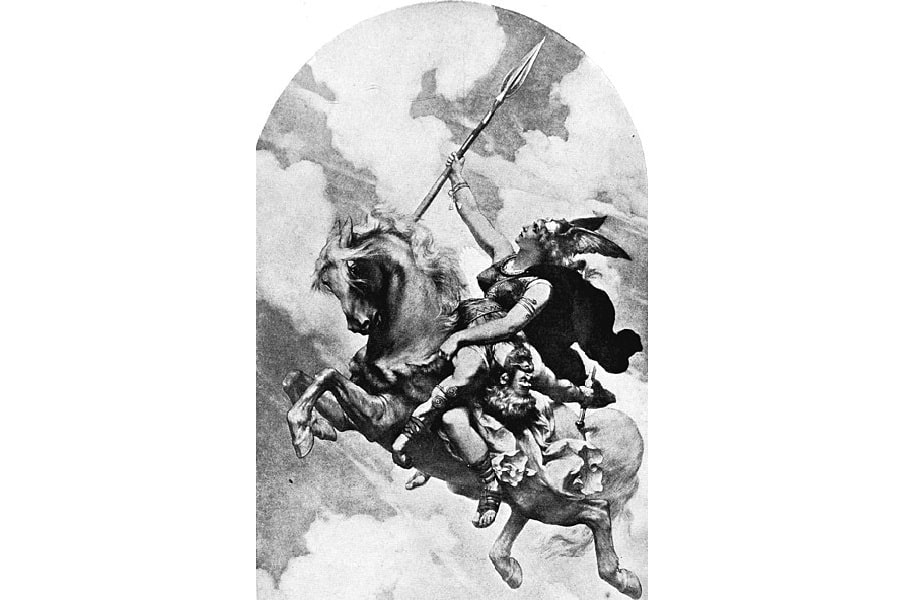

Valkyries were often depicted as fierce and beautiful women, often riding winged horses and wearing armor. They were skilled warriors in their own right, and some stories suggest they would also join the battle themselves.

Table of Contents

What are Valkyries?

The shortest, simplest answer is that the Valkyrie (or in Old Norse, Valkyrja) was a female warrior who traveled to a battlefield to choose who among the fallen was worthy to be brought to Valhalla – and ultimately fight alongside the Norse gods at Ragnarok. Like most short, simple answers, however, that one doesn’t tell the full story.

The consistent traits of Valkyries, at least in the later depictions, were that they were beautiful women. They could fly, change shape in at least a limited capacity, and were exceptional warriors.

The Valkyries would most commonly arm themselves with a spear. They could ride horses – Brynhildr was said to ride a winged horse similar to Pegasus – but it was not uncommon to depict a Valkyrie riding a wolf or boar as well.

But while the Valkyries were said to ferry the slain heroes to the afterlife in Norse mythology, there was more to who they were. And in Old Norse literature there was a surprising amount of diversity in their natures, abilities, and even their origins.

Gods and Mortals

The question of exactly who or what the Valkyries are isn’t a straightforward one. Their exact nature could vary across Norse literature, changing from one poem or story to another.

Classically, Valkyries are female spirits, neither gods nor mortals, but creations of Odin. In other depictions, however, the Valkyries seem to be classified as jötunn, and in others actual daughters of Odin himself. In many accounts, however – especially in later accounts – they are depicted as human women given supernatural powers when they take on this important role.

The Valkyrie Sigrún, for example, is encountered in the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, where she is described as the daughter of King Högni (and further described as a reincarnation of another Valkyrie, Sváva). She marries the hero of the tale, Helgi (named after the earlier hero Helgi Hjörvarðsson), and when he dies in battle, Sigrún dies of grief – only to again be reincarnated, this time as the Valkyrie Kára.

Likewise, the Valkyrie Brynhildr was described as being the daughter of King Budli. And other Valkyries are described as not only having mortal parents but taking mortal husbands and bearing children.

Maidens of Fate?

In the Gylfaginning from the Prose Edda, on the other hand, the Valkyries are said to be sent out by Odin to the scenes of battles where they actually decide which men will or won’t die and which side will prevail. That’s a change from the classic depiction, in which the Valkyries merely gather those dead who are deemed worthy of Valhalla, but don’t take an active role in the battle itself and may be an early conflation of the Valkyries with the weavers of fate, the Norns.

Compelling evidence of this is found in the Njáls saga, which tells the story of a man named Dörruð who witnesses twelve Valkyries entering a stone hut. Sneaking closer to spy on them, he sees them weaving on a loom while deciding who will live and die in an upcoming battle. This is a clear similarity to the Norns, and indeed, one of the Valkyries in the Gylfaginning was named Skuld – the same name as one of the Norns. She was even referred to in the story as “the youngest Norn”).

How Many Valkyries Were There?

It’s already been shown that, with mythology born in orally transmitted tales over a fairly broad region, consistency isn’t always a strong suit of Norse myths. The exact number of Valkyries – like the nature of the Valkyries – can change radically from story to story.

Part of this may well reflect that the strict definition and concept of Valkyries weren’t always consistent. Some saw them as a small council of Odin’s servants, others as an army in their own right. The varying notions we’ve already touched on regarding exactly what they were – and could do – clearly demonstrate that Valkyries were often interpreted and imagined differently, and this extends to the simple question of their numbers.

An Imprecise Count

An example of just how much variation there can be in the count of Valkyries comes in the Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar, from the Poetic Edda. In line 6, a young man (later named the hero Helgi) watches nine Valkyries riding by – yet later in line 28 of the same poem Helgi’s first mate is flying with the jötunn Hrimgerth, who notes that three times that many Valkyries watch over the hero.

In another poem, the Völuspá, a female seer (called a völva among the Norse) describes a group of six Valkyries by name, telling the god they were coming from some distant place and ready to ride over the earth. This reference is of note because it seems to suggest its list of six specific Valkyries is a complete set (almost in the vein of the Four Horsemen), rather than just a sample of some greater pool of available Valkyries.

More interestingly, it describes them as servants of the War Lord (or perhaps a War Goddess – though it’s possible this is just a reference to yet another Valkyrie). This, again, is an example of how the roles and functions of Valkyries went well beyond just collecting the worthy dead for Odin – and in this case, may connect to older Germanic traditions in which female spirits served a war god.

Yet another list is given in the poem Grímnismál, in which a disguised Odin is being kept as the prisoner of King Geirröth. When the king’s son comes to offer the prisoner kindness in the form of a drink, the disguised god lists some thirteen Valkyries who serve ale to the heroes in Valhalla. Again, this is not only a specific list – though in this case, there’s no indication it’s a complete one – but also describes another function of the Valkyries – serving the honored dead of Valhalla.

An Unknowable Number

Traditional sources describe the Valkyries as a set of nine or thirteen divine maidens (Richard Wagner’s opera Die Walküre, or “the Valkyrie” – from which the famous piece “Ride of the Valkyries” derives – takes its cue from this and lists nine). However, the references we’ve already seen – and there are many more – strongly suggest that these numbers aren’t sufficient (though some sources suggest the nine or thirteen numbers as being leaders of the Valkyries, rather than a complete count).

All told, there are some 39 specific names associated with Valkyries across the breadth of Norse mythology, including Hrist (mentioned by Odin as an ale-server), Gunnr (one of the six “war Valkyries” listed by the seer), and the most famous of the Valkyries, Brynhildr. Yet some sources put the count of Valkyries as high as 300 – and in the beliefs of everyday Norsemen, the number might have been much higher or indeed limitless.

Valkyries of Note

While many Valkyries were little more than names – and many times, less than that – some of them are much more developed. These Valkyries stand out not just because they have a greater presence in the myths in which they appear, but because they often take on roles or abilities beyond those of the typical Valkyrie.

Sigrún

As already mentioned in passing, Sigrún was the daughter of King Högni. She met and fell in love with the hero Helgi despite being betrothed to a hero named Hothbrodd, the son of a king named Granmarr – a problem Helgi solved by invading Ganmarr’s country and slaying everyone who opposed Helgi marrying her instead.

Unfortunately, this included Sigrún’s own father and one of her brothers. Her surviving brother, Dagr, was spared after swearing fealty to Helgi, but – honor bound to avenge his father – later slew the hero with a spear he’d been gifted by Odin.

Helgi was entombed in a burial mound, but one of Sigrún’s servants saw him and his retinue, in ghostly form, riding toward the barrow one evening. She informed her mistress, who went immediately to spend one last night with her beloved before he returned to Valhalla at dawn.

She sent her servant to watch the burial mound again the next night, but Helgi never returned. Sigrún, bereft, died of her grief – though the lovers were said to be later reincarnated as the hero Helgi Haddingjaskati and the Valkyrie Kára.

It’s interesting to note how little Sigrún’s status as a Valkyrie plays into her story. She rode on air and water, but beyond that detail, her tale would unfold much the same if she were just a mortal princess in the mold of the Greek Helen.

Thrud

The Valkyrie Thrud stands out not so much for what she does, but who she’s related to. One of the Valkyries described as serving ale in Valhalla to the honored dead, she shares a name with the daughter of Thor.

Given how often Valkyries were depicted as mortal women elevated by their role as Valkyries, this is a departure. Thrud was a goddess in her own right, making the position of Valkyrie – especially in the aspect of celestial barmaid – something of a demotion. It is possible that the name is a coincidence, but it seems unlikely that the name of a goddess – even a relatively minor one – would be applied to a Valkyrie by happenstance.

Eir

The classic role of Valkyries was to act as psychopomps – guides for the dead – to the bravest and best warriors destined for Valhalla. But the Valkyrie known as Eir (whose name literally means “mercy” or “help”) took on a very different, even contradictory role – healing the wounded and even raising the dead on the battlefield.

Adding to Eir’s uniqueness is that she, like Thrud, is conflated with a goddess. Eir is counted as a goddess of healing among the Aesir – though the very same source later lists her as a Valkyrie. Whether she fulfilled the conventional roles of a Valkyrie – or acted only in her unique role as a battlefield medic – is unknown.

Hildr

The Valkyrie known as Hildr (“Battle”) also had the ability to raise the dead, though she used it in a somewhat different manner than Eir. Also, unlike Eir, Hildr was a mortal woman, the daughter of King Högni.

While her father was away, Hildr had been taken in a raid by another king named Hedinn, who made her his wife. Furious, Högni pursued Hedinn all the way to the Orkney Islands near Scotland.

Hildr and her husband attempted to make peace with King Högni – Hildr offering him a necklace and Hedinn offering a large amount of gold – but the king would have none of it. The two armies prepared and a battle raged until nightfall when the two kings retreated to their respective camps.

During the night, Hildr went about the battlefield reviving all the dead who had fallen in the battle. The next morning the armies – again at full strength – fought throughout the day, and the next evening Hildr revived the fallen.

Seeing this as excellent training for Valhalla, Odin allowed it to continue – and it did. The unending Battle of the Heodenings, or Hjadning’s Strife, still rages each day, with Hildr restoring the dead each night.

This is, obviously, a far cry from bringing fallen warriors to their reward, and it paints Hildr as a much darker figure in Norse mythology. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Hildr was one of the six “war Valkyries” listed in the Völuspá.

Brynhildr

But no Valkyrie stands out as much as Brynhildr (or Brunhilda), whose story (the Germanic version) remains prominent due to being popularized by Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (“The Ring of the Nibelung”). Not only did her tale provide the original framework for the story of Sleeping Beauty, but it is perhaps the most fleshed-out myth regarding an individual Valkyrie.

As told in the Völsunga saga, the hero Sigurd, after slaying a dragon, comes upon a castle in the mountains. There he finds a beautiful woman, wearing armor so fitted it seems molded into her skin, asleep within a ring of fire. Sigurd cuts the woman free of the chainmail, which causes her to awaken.

Brynhildr’s Sin

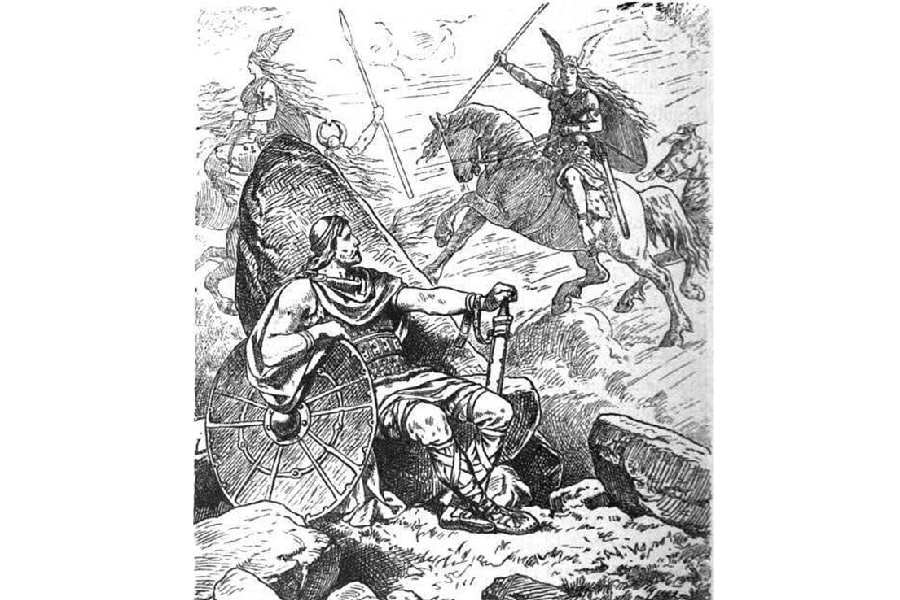

She reveals that her name is Brynhildr, daughter of Budli, and she had been a Valkyrie in the service of Odin. She had been sent to a battle between the kings Hjalmgunnar and Agnar, and ordered to decide the outcome (again, showing an aspect of Valkyrie mythology as not just psychopomps for the dead but actual agents of fate).

Odin’s preference had been for Hjalmgunnar, yet Brynhildr had decided to side instead with his opponent, Agnar. This is another tantalizing tidbit in Valkyrie lore – the notion of agency, that a Valkyrie has at least the capacity to make their own judgments even in defiance of Odin’s wishes.

This defiance was not without a price, however. To punish Brynhildr for her disobedience, Odin set her into a deep sleep, surrounding her in the ring of fire to remain until a man came to rescue and marry her. Brynhildr, for her part, swore she would marry only a man who never knew fear.

Sigurd’s Proposal

Smitten by the lovely Brynhildr, Sigurd was all too eager to fulfill the conditions of her release. And by braving the fire that surrounded her, he had proved himself worthy of doing so and proposed.

Brynhildr returns to the home of her sister, Bekkhild, who had married a great chief named Heimir. While she remained there, Sigurd also came to Heimir as he was traveling through, and he and Brynhildr spoke again.

The Valkyrie tells Sigurd that he would marry Gudrun, the daughter of King Giuki. This the hero vigorously refuted, saying that no king’s daughter could beguile him to forsake her.

Among his possessions was the magical ring Andvaranaut – a ring initially crafted by the dwarves which had been in the dragon’s hoard, and which aided its wearer in finding gold. Sigurd gifted this ring to Brynhildr as a sign of his proposal, and the two renewed their vow to marry before the hero departed.

Treacherous Magic

When Sigurd came to Guiki’s castle – still carrying the great treasure he’d accumulated – he was warmly received. He appears to have spent some time there, especially seeming to bond with Guiki’s sons, Gunnar and Hogni.

And in the course of that time, Sigurd spoke openly and lovingly about Brynhildr to his hosts. And this particularly caught the attention of Guiki’s wife, a sorceress named Grimhild.

Grimhild knew that Sigurd would make a great addition to their house if he married Guiki’s daughter, Gudrun – and likewise, that Brynhildr would make an excellent wife for Gunnar. So, she contrived a plan to use her magic to achieve both ends.

She created a potion to make Sigurd forget all memories of Brynhildr and served it to the hero at dinner. Meanwhile, she sent Gunnar to find Brynhildr.

Sigurd, his love or Brynhildr forgotten, married Gudrun exactly as the Valkyrie had feared. But Gunnar’s marriage to Brynhildr was not so easily accomplished.

The Test

Brynhildr was heartbroken at the news Sigurd had abandoned her, but she had still sworn to marry only a man without fear – a man who could brave the ring of fire that had held her. Gunnar made the attempt but could find no way through. He tried again with Sigurd’s own horse, thinking perhaps it would allow him to pass, but again he failed.

Grimhild worked her magic again. Under her spell, Sigurd shape-shifted into Gunnar, and the hero rode through the flames as before. Now believing that Gunnar had passed the test, she agreed to wed him.

The two spent three nights together, but Sigurd (still in his guise as Gunnar) kept a sword between them so the marriage was never consummated. When they parted, Sigurd took back Andvaranaut, which he passed to Gunnar before returning to his own form, leaving Brynhildr believing she had married the son of Guiki.

Tragic Ending

Inevitably, the ruse was discovered. In a quarrel between Brynhildr and Gudrun over whose husband was braver, Gudrun revealed the ruse by which Sigurd had passed through the flames that Gunnar could not.

Enraged, Brynhildr lied to Gunnar, telling him that Sigurd had slept with her after marrying her in disguise, and urged her husband to kill him for his betrayal. Both Gunnar and Hogni had sworn oaths to Sigurd, however, and were, therefore, afraid to act against him – instead, they gave their brother Gutthorm a potion that left him in a blind rage, during which he killed Sigurd in his sleep.

Brynhildr then killed Sigurd’s young son as Sigurd lay on his funeral pyre. Then, in despair, she threw herself on the pyre, and the two passed together into the domain of Hel.

Freyja the Valkyrie?

While the popular understanding is that the Valkyries were the ones to collect the dead, they were not the only ones. The sea-goddess Ran pulled down sailors to her underwater realm, and of course, Hel took the sick and elderly and those others who failed to die in battle.

But even the battlefield dead weren’t the exclusive right of the Valkyries. In some accounts, they only collected half of them, with the other half being collected by Freyja to be taken to Fólkvangr, a field she ruled over.

It was generally understood that Valhalla was for heroes and warriors of importance, and Fólkvangr was the destination for the common soldiers. But this seems a thin distinction. The possibility that Fólkvangr and Valhalla are not necessarily distinct locations raises the question of whether the goddess Freyja was a Valkyrie, or more closely connected to them than one might think.

Aside from collecting the battlefield dead, it’s also noted that Freyja had a cloak of feathers (which Loki stole on more than one occasion). Given that one of the most consistent aspects of Valkyries is their ability to fly, this seems like one more strand of connection.

But perhaps the greatest evidence comes from The Story of Hethin and Hogni, an old Icelandic story. The tale centers on Freyja, who at different points in the text seems to use the name Gondul – one of the known names of a Valkyrie – suggesting that the goddess might be counted among them, likely as their leader.

Source Material

The modern perception of Valkyries is largely a product of the Norse, especially in the Viking Age. It’s difficult to ignore their similarities in many ways to the shield maidens – female warriors who fought alongside men. Scholarship remains divided on whether they actually existed, but there’s no doubt that they were popular figures of Norse myth.

But other elements of Valkyries clearly evolved from earlier bits of Germanic lore, and many of those elements could still be seen in later Valkyrie myths. Chiefly, there are unmistakable hints of Valkyries in the German myths of swan maidens.

These maidens wore a swan’s skin or coat of feathers (similar to that belonging to Freyja, interestingly) which allowed them to transform into swans. Wearing them, a swan maiden could fly away to evade any prospective suitor – only by first capturing their coat, usually as they bathed, could the maiden be captured by a prospective husband.

It’s worth noting that Valkyries were said to transform into swans when they traveled to the battlefields of the mortal world, as Odin supposedly forbade them from being seen by mortals in human form (despite the numerous instances in the mythology of mortals doing just that). It was said that, if a mortal saw a Valkyrie, not in her swan form, she would lose her powers and be trapped in a marriage to the mortal – a fate which can be easily paralleled to the process of capturing a swan maiden in Germanic lore.

Dark Beginnings

But while Valkyries eventually came to be depicted as beautiful, often winged women (a likely element of Christian influence at the time the myths were finally written down), they do not seem to have begun that way. Some of the earliest descriptions of Valkyries are much more demonic in nature and hint that they would devour the dead on the battlefield.

This, again, ties to earlier Germanic lore and the idea of female spirits commanded by a war god – an idea that seems to be preserved in the seer’s vision from the Völuspá. And Valkyries were frequently associated with ravens and crows – carrion birds common on battlefields – which also ties them to the Irish badb, a seer who foretold the fates of warriors in battle who was likewise associated with such birds.

But the true origin of the “choosers of the slain” may be more prosaic. In his account of traveling in 10th Century Rus, the Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan describes a woman whose station was to oversee the killing of selected prisoners as a sacrifice. The idea that the myth of Valkyries began as priestesses overseeing sacrifices or battlefield divination is tantalizing, and it seems quite possible that such priestesses were the true prototype for the mythical beings who were later described as delivering the dead to Odin.