Like the Magna Carta, the US Constitution, or the Rights of Man, the Twelve Tables are rightly considered one of the foundational bits of legislation for Western law and legal practice. Spawned from a class conflict that was raging in Republican Rome, they outlined the rights of every citizen of the ancient state.

Table of Contents

What Were the Twelve Tables?

The Twelve Tables were a set of 12 tablets inscribed with Roman law that were displayed in the forum for everybody to see. Whilst they may have initially been made of wood, they were later remade in copper to be more durable.

They are considered to be the earliest document of Roman law and the first true bit of regularized legislation for the Roman civilization. The statutes in the Twelve Tables consolidated earlier traditions and customs into a definitive set of laws that outlined the rights of every citizen.

Displaying a relatively simple legal framework, they outline the proper procedure and punishment for various crimes, including fraud, theft, vandalism, murder, and improper burial. Examples of these crimes are listed with particular situations, and then punishments are prescribed in consequence.

They also go into some detail about court procedure and protocol and have a particular focus on the rights of defendants or litigants.

Why Were the Twelve Tables Written?

The Twelve Tables were commissioned as part of the effort to end the “Conflict of the Orders” between the Patricians and Plebeians. After the Roman citizens had thrown out their (mostly) tyrannous kings early in their history, the citizenry consisted of both the upper class (Patricians) and lower class (Plebeians), both of whom were free and could own slaves.

However, at this stage, only the Patricians could hold political or religious office, meaning that they monopolized the ability to make laws and enforce rules. They could therefore manipulate the law to their advantage, or completely deprive the poorer plebeian citizens of their rights, which many would have been unaware of anyway.

Whilst this state of affairs was in some ways very lucrative for the Patricians, the Plebeians made up the labor force of the early Roman civilization. When pushed to insurrection then, the Plebeians could completely interrupt the primitive economy of the day and cause a lot of problems for the aristocracy in turn.

And indeed, the total unbalance of power led to a series of “secessions” by the Plebeians who walked out of the city in protest of their oppression. By the middle of the 6th century BC, two had already occurred and caused alarm to the aristocrats of early Rome.

As part of an enduring attempt to address this then, the idea was brought about to establish the rights of all Roman citizens and have them publicized and displayed in a public space. That way, abuses could be curtailed, and everybody could be aware of their legal rights when they came into question. Hence, the Twelve Tables were commissioned to fulfill this need.

Background and Composition of the Tables

The historical sources claim that in 462 BC a representative of the Plebeians, called Terentius Harsa, requested that the customary laws that had so far prevailed be properly recorded and made publicly available for all to be aware of.

The request came at a moment of heightened tensions between the different social classes and was seen as a hopeful solution to the problems that beset the Early Republic. Whilst it seems as though the Patricians initially rejected to acquiesce to these requests, apparently after 8 years of civil strife, they relented.

We are told then that a three-person commission was sent to Greece in order to study the laws of the Greeks, particularly those of the Athenian lawgiver Solon – a renowned figure of Greek antiquity.

READ MORE: Ancient Greece Timeline: Pre-Mycenaean to the Roman Conquest

Upon returning to Rome, a board of ten Patrician magistrates, known as the decemviri legibus scribundis, was set up in order to commission a written legal code for the first time in their civilization’s history. We are told that in 450 BC, the commission published 10 sets of laws (tables).

However, the content of these was quickly considered unsatisfactory by the public. Consequently, another two tablets were added, making the complete set of twelve in 449 BC. Accepted by everyone, they were then inscribed and posted up in a public place (believed to be in the middle of the forum).

Did Anything Precede Them, in Terms of Legislation or Law?

As alluded to above, the Twelve Tables were the first piece of official, written legislation commissioned by the Roman state to cover all of its citizens and their daily life.

Before this, the patricians had preferred a more informal, ambiguous, and flexible system of law that could be adapted as they saw fit and administered by political or religious officials they could control.

Individual matters would be discussed in assemblies, and both the Plebeians and Patricians possessed their own, although the Patriciate assembly was the only one with real power. Legal resolutions could be passed on specific matters, but these were decided on a case-by-case basis.

Judicial decision-making was closely tied to the religious and ethical system of Early Rome, so priests (known as Pontifices) would often be the arbitrators of judicial disputes if something could not be resolved easily amongst a family or set of families.

Such a case would be significant, as Rome began as (and remained) a patriarchal and patrilineal society, wherein family disputes would often be judged and resolved by the patriarch. Its social structure was also heavily oriented around different tribes and families, with plebeian families each having the patrician family that they effectively served.

The heads of Plebeian familia could therefore adjudicate on internal issues amongst themselves, but if the issue was bigger than a simple family dispute, it would fall to the Patrician Pontifices instead. This meant that abuse of the law was rife as poorer, illiterate, and uneducated plebeians stood little chance of having their cases heard fairly.

Nonetheless, some customary laws and a basic legal framework were supposed to exist, although it was often exploited by tyrannous kings or Patrician oligarchs. Moreover, the Patricians could hold multiple offices that affected the everyday administration of the city, whereas the Plebeians only possessed The Tribune of the Plebs that could seriously influence events.

This position was borne out of an earlier episode of The Conflict of the Orders, wherein the Plebeians collectively walked out of the city and away from their work in protest. This “First Secession of the Plebs” shook up the Patricians, who subsequently granted the Plebeians their own Tribune who could speak for their interests to the Patricians.

How Do We Know about the Twelve Tables?

Given how old the tables are, it is remarkable that we still know about them – although it is certainly not in their original format. The original tables were thought to be destroyed during the sack of Rome by the Gauls, led by Brennus, in 390 BC.

They were subsequently drawn up again from the knowledge of their original contents, but it is likely that some of the wording was slightly changed. However, these subsequent renditions do not survive either, as is the case with much of the ancient city’s archaeological record.

Instead, we know about them through the comments and quotations of later lawyers, historians, and social commentators, who no doubt tweaked their language further, with each new rendition. We learn from Cicero and Varro that they were a central part of an aristocratic child’s education, and many commentaries were written on them.

Additionally, we know about the events surrounding their composition because of historians such as Livy who recounted the story, as he understood it, or wished for it to be remembered. Later historians such as Diodorus Siculus then adapted the accounts for their own ends and their contemporary readers.

Moreover, many of the legal statutes mentioned in the Twelve Tables are quoted at length in the later Digest of Justinian which accumulated and collated the whole corpus of Roman law that existed up until its composition in the 6th century AD. In many ways, the Twelve Tables were an integral precursor to the later Digest.

Should We Believe the Accounts of Their Composition?

Historians now are skeptical about some aspects of Livy’s account of the Twelve Tables and their composition, as well as the remarks of later commentators. For one, the story that the three-man commission toured Greece to investigate their legal systems, before returning to Rome, seems suspect.

Whilst it remains possible that this was the case, it is more likely to be a familiar attempt to connect the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome. At this time, there is little to no evidence that Rome, as a fledgling civilization, had any interaction with the Greek city-states across the Adriatic Sea.

Instead, it is much more likely, and now widely believed, that the laws are heavily influenced by the Etruscans and their religious customs. Besides this, the idea that the first ten tables were published, only to be rejected is doubted in some circles.

There is also the obvious issue that Livy was not contemporary of the events and instead wrote more than four centuries after the events. The same issue is therefore accentuated by later writers such as Diodorus Siculus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and Sextus Pomponius.

Regardless of these issues, however, the account of the Tables’ composition is generally held to be a reliable outline of events by modern analysts.

The Content of the Twelve Tables

As discussed, the twelve tables in their content, helped to establish social protection and civil rights for every Roman citizen. Whilst they cover a variety of different societal themes and subjects, they still reflect the relative simplicity of Rome at this time, as a localized, almost wholly agrarian city-state.

It is therefore far from complete, and as we shall see, was not sufficient to cover all of the areas of jurisprudence that the future civilization was to incorporate. Instead, most of the laws are reiterations and clarifications of common and recurrent customs that were already observed or understood by areas of society before the tables were written.

On top of this, the language and phrasing used are sometimes difficult to understand or properly translate. This is in part because of the incomplete record we have of them, as well as the fact that they would have been initially written in a very primitive form of Latin, before being recurrently revised and adjusted – not always faithfully.

Cicero, for example, explains that some of the statutes people did not really understand and were unable to interpret properly for legal matters. Much then could fall to interpretation, with one judge’s perspective differing a lot from the next.

For the most part, private law is covered, including provisions for family relations, wills, inheritance, property, and contracts. Therefore, a lot of the judicial procedure for these kinds of cases was covered, as well as the ways decisions were supposed to be enforced.

More specifically, the Tables covered the following subjects:

1. Normal Court Procedure

In order to standardize the way that cases were heard and conducted, the first of the Tables covered court procedure. This revolved around the way that a plaintiff and defendant were supposed to conduct themselves, as well the options for different circumstances and situations, including when age or illness prevented somebody from turning up to trial.

It similarly covered what was to be done if the defendant or plaintiff did not turn up, as well as how long trials were supposed to take.

2. Further Court Proceedings and Financial Recommendations

Following on from the first Table, Table II further delineated aspects of court procedure, as well as outlining how much money should be spent on different types of trials. It also covered other expedient solutions to unfortunate situations, such as the impairment of the judge, or the illness of the defendant.

If the illness was so severe that they were unable to attend, the trial could be postponed. Finally, it also adumbrated the rules of how evidence should be presented, and by whom.

3. Sentences and Judgments

Having established the proper procedure and order of events, the third Table then outlined the usual sentences and execution of judgments.

This included the penalty for stealing something of value from somebody (usually double its value), as well as how long somebody was given to pay the debt (usually 30 days); if they chose not to pay within that time, they should be arrested and brought into court.

If they were still unable to pay, they could be held for sixty days and perhaps made to do hard labor, after which they could subsequently be sold to slavery if they were still unable to pay their debt.

4. The Rights of Patriarchs

The next Table then covered the specific rights of patriarchs within their family network or familia. It mainly covers various conditions of inheritance – for example, that sons will be the inheritors of their father’s estate. Additionally, it covered the conditions by which the patriarch could effectively divorce his wife.

In an early sign of the disablism that was endemic to Roman society, this Table also declared that fathers should euthanize badly deformed children themselves. This tradition of “discarding” deformed babies was also prominent in certain Greek states, particularly Ancient Sparta.

In a society where manhood and even late childhood were molded by toilsome work or war, deformed children were cruelly seen as liabilities that families could not support.

5. Women’s Estates and Guardianship

As one would expect from an early civilization in which the public and private politics of the day were dominated by men, women’s rights of ownership and freedom were heavily restricted. Women themselves were in many ways conceptualized as objects that had to be properly guarded and looked after.

The Fifth Table, therefore, outlined the procedure for guardianship of women, usually by the father, or their husband if they had been married. The only exception to this was for Vestal Virgins, who played a very important religious role throughout the duration of Roman history.

READ MORE: The Complete Roman Empire Timeline: Dates of Battles, Emperors, and Events

6. Ownership and Possession

In the Sixth Table, the fundamental principles of ownership and possession are outlined. This covered anything from timber (which is discussed explicitly in this Table) to women again, as it is detailed that when a woman resides in the house of a man for more than three days, she becomes his legal wife.

To escape this situation, the wife was supposed to “absent herself for three days” again, to reverse the procedure, although it is not clear how this aligns with the other claims of ownership that males would usually exercise of their female counterparts.

7. Further Detail on Property

Having already established some of the basics about the ownership of materials and wives, the Seventh Table then looked at the specifications and conditions of the property further. The Table itself is very incomplete, but from what we can tell it details different types of households and how their land is supposed to be managed.

This included the width of roads and their repair, as well as the branches of trees and how they should be properly pruned. It also covered the proper conduct for dealing with boundaries between neighbors, to the extent that it covered what could happen if a tree had caused damage to a boundary.

It also covered some aspects of freeing or “manumitting” slaves, if it was covered in an owner’s will.

8. Magic and Crimes Against Other Roman Citizens

In line with the fact that the Roman religion encompassed a broad swathe of different mythological, mystical, and magical beliefs about the ancient world, the Eighth Table prohibited many acts of magic or incantation. The penalties for transgressing such laws were often severe – singing or composing an incantation that could cause dishonor or disgrace to another person permitted the death penalty.

The rest of the Table covers various different crimes one could commit against another, including breaking another citizen’s limb or bone, breaking another freedman’s bone, felling another person’s tree, or burning another’s property – all with the designated penalties to go along with the crime.

In fact, this Table is one of the most complete we have, or at least it appears to be, perhaps because of the large list of crimes and their punishments that are detailed. Theft, damage, and assault are all explored in different categories and situations, with particular items like a loincloth or platter given as examples.

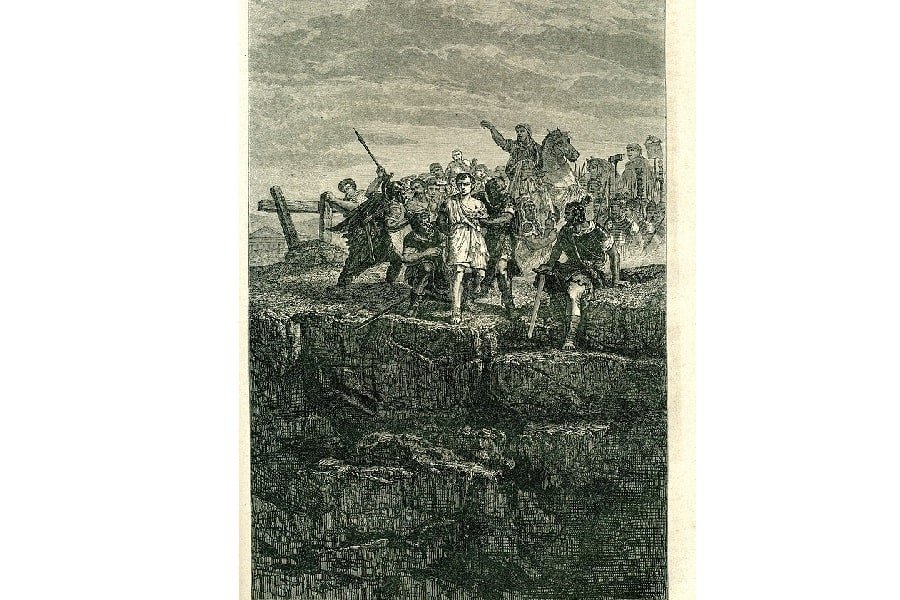

The crime of giving false testimony is also covered, wherein the criminal “shall be flung from the Tarpeian Rock.” “Nocturnal meetings” are not allowed in the city and the improper administering of drugs is warned against as well.

9. Public Law

The Ninth Table then covers more public forms of law, including the requirements for passing capital punishment – it was only to be passed by the “Greatest Assembly.” This careful approach to capital punishment is further emphasized in another section of the table which stresses that nobody shall be put to death without a trial.

This fundamental law remained important throughout the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, even though it was often ignored by tyrannous statesmen and capricious emperors. The famous statesman Cicero had to doggedly defend his decision to execute the public enemy Catiline without a trial.

The ninth Table also covers the punishment for a judge or arbiter involved in a legal case who has taken a bribe – the punishment being death. Anybody who aids a public enemy, or betrays a citizen to a public enemy shall also, according to the Table, be punished capitally.

10. Sacred Law around Burials

Another of the Tables which we have more remaining than the others is the Tenth Table, which covers various aspects of sacred or religious law, with a particular focus on burial customs. One of the very interesting statutes states that a dead person may not be buried or cremated inside the city itself.

Whilst this may have had some religious significance, it is also believed this was enforced in order to combat the spread of disease. What follows are various restrictions on what can be buried with the corpse, and what cannot be poured on it – for example, a myrrh-spiced drink.

Women’s behavior around death was also curtailed, as they were prohibited from “tearing their cheeks” or making a “sorrowful outcry” at a funeral or because of one. Additionally, the expenses involved in a funeral were curtailed – although this definitely became obsolete for later figures.

11. Additional Laws, Including Patrician-Plebeian Intermarriage

Whilst these Twelve Tables no doubt helped to assuage the hostility and alienation between the Patricians and Plebeians it is clear from one of the statutes in the Eleventh Table that things were far from friendly.

The two classes were forbidden from intermarrying in this Table, clearly in an effort to keep each class pure as possible. Whilst this did not last permanently, and the two classes remained in existence throughout the empire (although to a much-lessened degree), for a long time they did keep themselves separate, and the “Conflict of the Orders” was far from properly over.

Besides this, the Eleventh Table is largely lost, except for a statute regulating the days that were permissible for legal proceedings and judgments.

12. Further Additional and Miscellaneous Laws

This final Table (as well as the Eleventh) really seems more like appendices added to the first ten because of their lack of a unifying theme or subject. Table XII covers very precise laws such as one surrounding the punishment for a person who agrees to pay for a sacrificial animal, but then does not actually pay.

It also covers what happens when a slave commits a theft or damages a property, although that statute remains incomplete. Perhaps most interestingly, there is a statute ordering that “whatever the people decide last shall be legally valid.” This seems to suggest that agreement had to be made for a binding decision between the assemblies of people organized.

The Significance of the Twelve Tables

The significance of the Twelve Tables still reverberates into the modern world and its multifarious legal systems. For the Romans as well, they remained the only attempt by that civilization to publish a comprehensive set of laws that was supposed to cover all of society, for almost a thousand years.

Although legal reforms did follow soon after their publication, the Tables remained the foundation through which ideas such as justice, punishment, and equality were disseminated and developed in the Roman world. For the Plebeians specifically, they also helped to curb the abuse of power that the patricians held over them, making a fairer society for every citizen.

It was not really until the 6th century AD, and The Digest of Justinian I, that a comprehensive body of law was published again in the Roman/Byzantine world. For their part, the Tables were also very influential in molding the Digest and are often quoted inside.

Many of the principles contained within the Tables are also pervasive throughout the Digest and really, through every other legal text of the Western tradition.

This is not to say however, that laws, or statutes, were not subsequently passed by the senate, assemblies, or emperor, but the statutes that were passed were not a body of laws for the whole of society. Instead, the statutes covered very specific things that happened to be causing issues at that particular time.

Moreover, all of these worked off the legal foundations laid out in the Twelve Tables, often by interpreting the principles that pervaded the original legislation. In this sense, the Romans have commonly been accused of demonstrating a distinct disinclination to move too far away from these traditional customs and legal precepts.

For them, these Twelve Tables helped to embody many aspects of the traditional body of Roman ethics and religion, which should not be too far revised or disrespected. This tied into a deeply held respect that the Romans held for their ancestors, as well as their customs and ethics.

Did the Twelve Tables Help End the Conflict of the Orders?

As has been alluded to in various places above, the Twelve Tables themselves did not end the Conflict of the Orders. In fact, the Twelve Tables, besides their significance for Roman law more generally, are seen as more of a stopgap, or early stage of appeasement for the plebeians than anything that substantially altered events.

Whilst they did codify and publish the rights that every Roman was supposed to be due, they still heavily favored the Patricians, who retained their monopoly on religious and political positions. Decision-making was therefore still very much in the hands of the privileged class.

This also meant that there would no doubt still have been a considerable amount of unfair legal proceedings, to the detriment of the plebeian class. Moreover, there were a whole host of other laws that were subsequently passed before the conflict was considered over.

Indeed, the Conflict of the Orders is held to have lasted until 287 BC – more than a century and a half after the Twelve Tables were completed. During this time, the plebeians remained completely unequal to the Patricians, until the gulf inequality began to be slowly eroded.

It was not until Plebeians could actually hold different offices (besides from Tribune of the Plebs) and that their assemblies could actually have some power over Patrician affairs, that a form of equality was ever really held.

Even then, up until the late 2nd and early 3rd century onwards, the label of Patrician still retained an air of haughty superiority over their Plebeian counterparts.

The arrival of the Roman emperors however, from around 27BC onwards, began a steady erosion of their significance, as it began to matter much more how close you were to the emperor, or how important you were more locally, in the empire’s vast provinces.

READ MORE: The Worst Roman Emperors

The Later Legacy of the Twelve Tables

As mentioned above, they have also possessed a lot of significance for modern legal systems. For example, James Madison – one of the Founding Fathers of America – stressed the importance of the twelve tables in crafting the United States Bill of Rights.

The idea of private property was also given enduring and explicit expression in the Tables, paving the way for its broad conceptualization in the modern world. In most legal firms and organizations, having some knowledge of the Twelve Tables is often a preliminary part of training.

Moreover, the whole notion behind the Twelve Tables, as a law common to all, or a jus commune, was foundational for the later inceptions and developments of “common law” and “civic law”. These two types of legal frameworks constitute the bulk of the world’s legal systems today.

Whilst their value for later legal systems has been eclipsed by the comprehensive Digest of Justinian mentioned above, they are without a doubt a foundational bit of legislation for the western legal tradition.

They also help to express the ethos of early Rome and display its relatively organized and coherent approach to societal harmony and values.