It’s April 18, 1775, in Boston, Massachusetts. The eve of the American Revolution, although you don’t know it yet.

It’s been five years since you arrived with your family to the North American colonies, and while life has been tough, especially during the first years when you worked as an indentured servant to pay for your voyage, things are good.

You met a man at church, William Hawthorne, who runs a warehouse down by the docks, and he offered you a paying job loading and unloading the ships that entered Boston Harbor. Hard work. Modest work. But good work. Much better than no work.

Recommended Reading

Louisiana Purchase: Date, Cost, Importance, and Results

The American Revolution: The Dates, Causes, and Timeline in the Fight for Independence

How Old Is the United States of America?

For you, the evening of April 18th was a night like any other. The children were fed until filled – thanks to God – and you’d managed to spend an hour sitting with them by the fire reading from the Bible and discussing its words.

Your life in Boston is not glamorous, but it’s peaceful and prosperous, and this has helped you to forget all that you left behind in London. And while you remain a subject of the British Empire, you’re also now an “American.” Your trip across the Atlantic has given you the chance to reshape your identity and to live a life that was once nothing more than a dream.

In recent years, radicals and other outspoken folk have been raising a ruckus in protest of the king. Leaflets are passed around in the streets of Boston, and people hold secret meetings all across the American colonies to discuss the idea of revolution.

A man once stopped you on the side of the road, asking, “What say you to the tyranny of the Crown?” and pointing to a newspaper article announcing the passage of the Coercive Acts — a punishment dealt out thanks to Sam Adams and his gang’s decision to throw thousands of pounds of tea into Boston Harbor in protest of the Tea Act.

In keeping with your quiet, honest ways, you pushed past him. “Leave a man in peace to walk home to his wife and children,” you grumbled, scowling and trying to keep your head down.

As you walked away, though, you wondered if the man would now count you as a loyalist — a decision that would have put a target on your back in such an era of tension.

In truth, you’re neither a loyalist nor a patriot. You’re just trying to get by, grateful for what you have and wary of wanting what you don’t. But like any human being, you can’t help but think of what’s to come. Your dock job pays enough for you to save, and you hope to one day buy some property, maybe out by Watertown, where things are quieter. And with property comes the right to vote and participate in the affairs of the town. But the Crown is doing all it can to hold back the right to self-rule in America. Maybe a change would be nice.

“Ay! Here I go again,” you say to yourself, “letting my mind run amok with ideas.” With that, you push your revolutionary sympathy from your mind and blow out the candle before bed.

This inner debate has gone on for some time, and it’s gotten more pronounced as the revolutionaries gain more support around the American colonies.

But as your divided mind rests on your straw pillow on the night of April 17, 1775, there are men out there making a decision for you.

Paul Revere, Samuel Prescott, and William Dawes Prescott are mobilizing to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who are staying in Lexington, Massachusetts, of the British Army’s plans to arrest them, a maneuver that led to the first shots of the American Revolution and the outbreak of the Revolutionary war.

This means that by the time you wake up on April 18, 1776, you will no longer be able to stand in the middle, content with your life and tolerant of the “tyrant” king. You will be forced to make a choice, to pick sides, in one of the most shocking and transformative experiments of human history.

The American Revolution was far more than an uprising of discontented colonists against the British king. It was a world war that involved multiple nations fighting battles on land and sea around the globe.

Table of Contents

The Origins of the American Revolution

The American Revolution cannot be linked to a single moment such as the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Rather, it was a gradual shift in popular thinking about the relation between ordinary people and government power. April 18, 1775, was a turning point in history, but it’s not as if those living in the American colonies just woke up that day and decided to try and overthrow arguably one of the most powerful monarchies in the world.

Instead, Revolution Stew had been brewing in America for many decades, if not more, which made the shots fired on Lexington Green not much more than the first domino to fall.

The Roots of Self Rule

Imagine yourself as a teenager sent off to summer camp. While being so far from home and left to fend for yourself might be nerve wracking at first, once you get over the initial shock, you soon realize you’re freer than you’ve ever been.

No parents to tell you when to go to bed, or hounding you to get a job, or commenting on the clothes you wear. Even if you’ve never had this experience, you can surely relate to how good it would feel — to be able to make your own decisions, based on what you know to be right for yourself.

But when you return home, likely the week before school, you would find yourself once again within the grasp of tyranny. Your parents might respect the fact you’re now more independent and self-sufficient, but they are not likely to let you roam free and do as you please as you did while far away from the confines of home.

Your parents might feel conflicted at this point. On the one hand, they’re happy to see you grow, but you’re now causing them more problems than ever (as if raising a regular teenager wasn’t already enough).

And this is exactly how things went down before the outbreak of the American Revolution — the king and Parliament had been content to give the American colonies freedom when it was profitable, but when they decided to tighten up and try to take more from their teenage children across the pond, the kids fought back, rebelled, and eventually ran straight away from home, never stopping to look back.

Jamestown and Plymouth: The First Succesful American Colonies

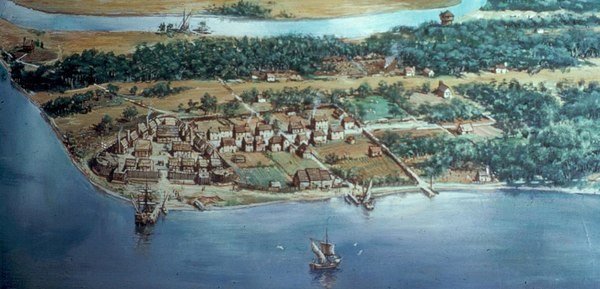

King James I started this mess when he created the London Company by royal charter in 1606 to settle the “New World.” He wanted to grow his empire, and he could only do so by sending out his supposedly loyal subjects to seek new lands and opportunities.

Initially, his plan seemed doomed to fail, as the first settlers in Jamestown nearly died from the harsh conditions and hostile natives. But over time, they learned how to survive, and one tactic was to cooperate.

Surviving in the New World required settlers to work together. First, they needed to organize a defense from the local populations who rightly saw Europeans as a threat, and they also needed to coordinate the production of food and other crops that would serve as the base for their sustenance. This lead to the formation of the General Assembly in 1619, which was meant to govern all the lands of the colony eventually known as Virginia.

The folks in Massachusetts (who settled Plymouth) did something similar by signing the Mayflower Compact in 1620. This document essentially said that the colonists sailing on the Mayflower, the ship used to transport Puritan settlers to the New World, would be responsible for governing themselves. It established a majority-rule system, and by signing it, the settlers agreed to follow the rules made by the group for the sake of survival.

The Spread of Self-Rule

Over time, all the colonies in the New World developed some system of self-government, which would have changed the way they perceived the role of the king in their lives.

Of course, the king was still in charge, but in the 1620s, it’s not like there were cell phones equipped with email and FaceTime for the king and his governors to use to monitor the actions of their subjects. Instead, there was an ocean that took approximately six weeks (when the weather was good) to cross in between England and its American colonies.

This distance made it difficult for the Crown to regulate activity in the American colonies, and it empowered the people living there to take greater ownership in the affairs of their government.

However, things changed post-1689, after the Glorious Revolution and the signing of the Bill of Rights of 1689 in England. These events changed England and its colonies forever because they established Parliament, and not the king, as the head of the British administration.

This would have tremendous, although not immediate, consequences in the colonies because it brought up a key issue: the American colonies had no representation in Parliament.

At first, this wasn’t a big deal. But over the course of the 18th century, it would be at the center of revolutionary rhetoric and eventually push the American colonists to take drastic action.

“Taxation Without Representation”

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the British Empire’s colonial experiment in North America went from being a near giant “whoops” to a huge success. People from all over overcrowded and stinky Europe decided to up and move across the Atlantic in search of a better life, leading to steady population and economic growth in the New World.

Once there, those who made the journey were met with a hard life, but it was one that rewarded hard work and perseverance, and that also gave them considerably more freedom than they had back at home.

Cash crops such as tobacco and sugar, as well as cotton, were grown in the American colonies and shipped back to Great Britain and to the rest of the world, making the British Crown a pretty penny along the way.

READ MORE: Who Invented the Cotton Gin? Eli Whitney and Cotton Gin Impact on America

The fur trade was also a major source of income, especially for the French colonies in Canada. And of course, people were also getting rich in the trade of other people; the first African slaves arrived in the Americas in the early 1600s, and by 1700, the international slave trade was in full force.

So unless you were an African slave — ripped from your homeland, shoved in the cargo hold of a ship for six weeks, sold into bondage, and forced to work the fields for free under threat of abuse or death — life in the American colonies was probably pretty good. But as we know, all good things must come to an end, and in this case, that end was brought on by history’s favorite fiend: war.

The French and Indian War

American Indian tribes were divided over whether to support Great Britain or the Patriots during the American Revolution. Aware of the riches available in the New World, Britain and France began fighting in 1754 to control territory in modern-day Ohio. This lead to an all-out war in which both sides built coalitions with native nations to help them win, hence the name “French and Indian War.”

Fighting took place between 1754 and 1763, and many consider this war to be the first part of a larger conflict between France and Britain, most commonly known as the Seven Years’ War.

For the American colonists, this was significant for a number of reasons.

The first is that many colonists served in the British army during the war, as one would expect from any loyal subject. However, instead of receiving a thank you hug and a handshake from the king and Parliament, the British authority responded to the war by levying new taxes and trade regulations they claimed were going to help pay for the growing expense of “guaranteeing colonial safety.”

‘Yeah, right!’ exclaimed the colonial merchants in unison. They saw this move for what it was: an attempt to extract more money from the colonies and line their own pockets.

The British government had been trying this since the early years of colonialism (the Dominion of New England, the Navigation Acts, the Molasses Tax… the list goes on), and it always met fierce protest from the American colonies, which forced the British administration to repeal its laws and maintain colonial freedom.

However, after the French and Indian War, the British authority had no choice but to try harder to control the colonies, and so it went all-out with taxes, a move that ultimately had disastrous effects. Frontier warfare during the American Revolution was particularly brutal and numerous atrocities were committed by settlers and native tribes alike.

The Proclamation of 1763

Perhaps the first thing to really tick the colonists off and set the wheels of revolution in motion was the Proclamation of 1763. It was made the same year as the Treaty of Paris — which ended fighting between the British and the French — and it basically said that colonists could not settle west of the Appalachian Mountains. This prevented many colonists from moving onto their hard earned lands, awarded to them by the king for their service in the Revolutionary war, which would have been irritating, to put it mildly.

The colonists took up in protest of this proclamation, and after a series of treaties with Native American nations, the boundary line was moved considerably farther west, which opened up most of Kentucky and Virginia to colonial settlement.

Yet, even though the colonists eventually got what they wanted, they didn’t get it without a fight, something they wouldn’t forget in the coming years.

After the French and Indian War, the colonies gained much more independence due to salutary neglect, which was the British Empire’s policy of allowing the colonies to violate strict trade restrictions to encourage economic growth. During the Revolutionary War, Patriots sought to gain formal acknowledgment of this policy through independence. Confident that independence lay ahead, Patriots isolated many fellow colonists by resorting to violence against tax collectors and pressuring others to declare a position in this conflict.

Here Come the Taxes

In addition to the Proclamation of 1763, Parliament, in an attempt to make more money off the colonies in accordance with the approach of mercantilism, and also to regulate trade, began imposing taxes on the American colonies for basic goods.

The first of these acts was the Currency Act (1764), which restricted the use of paper money in the colonies. Next came the Sugar Act (1764), which placed a tax on sugar (duh), and was meant to make the Molasses Act (1733) more effective by reducing the rate of and improving collection mechanisms.

However, the Sugar Act went further by limiting other aspects of colonial trade. For example, the act meant that colonists needed to buy all their lumber from Britain, and it required ship captains to keep detailed lists of the goods they carried onboard. Should they be stopped and inspected by naval ships when at sea, or by port officials after arriving, and the contents on board did not match their list, these captains would be tried in imperial courts rather than colonial ones. This raised the stakes, as colonial courts tended to be less strict on smuggling than those controlled directly by the Crown and Parliament.

This brings us to an interesting point: many of the people who were the most opposed to the law passed by Parliament throughout the final half of the 18th century were smugglers. They were breaking the law because it was more profitable to do so, and then when the British government tried to enforce those laws, the smugglers claimed they were unfair.

As it turns out, their dislike of these laws proved to be the perfect opportunity to provoke the British. And when the British responded with more attempts to control the colonies, all that did was spread the idea of revolution to even more parts of society.

Of course, it also helped that the philosophers in America at the time used those “unfair laws” as an opportunity to wax prophetically about the ills of a monarchy and to fill people’s heads with the idea that they could do it better on their own. But it’s worth wondering how much affect all of this had on the lives of those who were just trying to make an honest living — how would they have felt about a revolution if these smugglers had decided to just follow the rules?

(Maybe the same thing would have happened. We’ll never know, but it’s interesting to remember how this was a part of the nation’s founding. Some could say that the culture of today’s United States tends to try and work around its law and its government, which could very well be a remnant from the nation’s beginnings.)

After the Sugar Act, in 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which required printed materials in the colonies to be sold on paper printed in London. To verify the tax had been paid, the paper had to have a revenue “stamp” on it. By now, the issue had spread beyond just smugglers and merchants. Every day people were starting to feel the injustice and they were getting closer and closer to taking action.

Protesting the Taxes

The Stamp Tax, although quite low, angered the colonists greatly because it, like all other taxes in the colonies, had been levied in Parliament where the colonists had no representation.

The colonists, who had been used to self-ruling for many years, felt their local governments were the only ones who had the right to raise taxes. But the British Parliament, who saw the colonies as no more than corporations under the control of the government, felt they had the right to do as they pleased with “their” colonies.

This argument obviously did not sit well with the colonists, and they began organizing in response. They formed the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, which met to petition the king and was the first example of colonial-wide cooperation in protest of the British government.

This congress also issued the Declaration of Rights and Grievances to Parliament to formally announce their dissatisfaction with the state of affairs between the colonies and the British government.

The Sons of Liberty, a group of radicals who would protest by burning effigies and intimidating members of court, also became active during this period, as well as the Committees of Correspondence, which were shadow governments formed by the colonies that existed throughout all of Colonial America that worked to organize resistance to the British government.

In 1766, the Stamp Act was repealed due to the government’s inability to collect it. But Parliament passed the Declaratory Act at the same time, which stated that it had the right to tax the colonies in the exact same way it could back in England. This was effectively a giant middle finger to the colonies from across the pond.

The Townshend Acts

Although the colonists had been fiercely protesting these new taxes and laws, the British administration didn’t really seem to care all that much. They figured they were in the right doing as they were doing, and continued to push forward with their attempts to regulate trade and increase revenue from the colonies.

In 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts. These laws imposed new taxes on items such as paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea, established a Customs Board in Boston to regulate trade, set up new courts to prosecute smugglers that did not include a local jury, and gave British officials the right to search colonists’ homes and businesses with little probable cause.

Those of us looking back at this time now see this happening and say to ourselves, ‘What were you thinking?!’ It feels kind of like when the protagonist of a scary movie decides to walk down the dark alley even though everyone knows doing so will get them killed.

Things were no different for the British Parliament. Up until this point, no tax or regulation imposed on the colonies had been welcomed, so why Parliament thought upping the ante would work is a mystery. But, just as English speaking tourists respond to people who don’t speak English by shouting the same words more loudly and waving their hands, the British government responded to colonial protests with more taxes and more laws.

But, shockingly, this time, the colonial response was much stronger. Samuel Adams, along with James Otis Jr., who by now had become prominent figures of the anti-British movement, wrote the “Massachusetts Circular Letter” which made its way to other colonial governments. This document, along with John Dickinson’s “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” expressed the urgency in responding to these new laws, and encouraged North American colonists to take action. The response was an eager and widespread boycott of British goods.

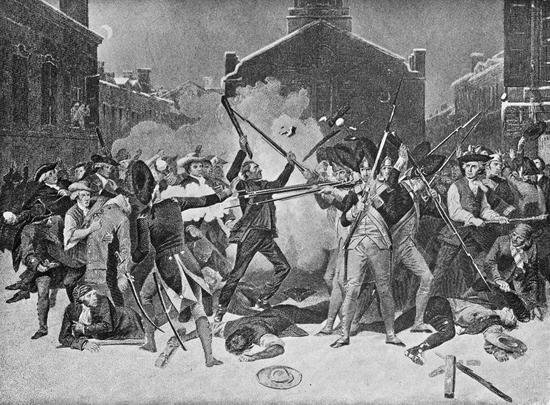

The Boston Massacre | The Incident on King’s Street

In 1770, an American named Edward Garrick came to the Custom House on King Street in Boston to complain that a British officer had left his bill unpaid at his master’s wig shop. Insults were exchanged, with each side reportedly telling your momma jokes and discussing the strength of their big brothers, before a rowdy crowd gathered and turned the night violent.

British soldiers ended up firing into the crowd of colonists, despite never receiving a direct order to do so, immediately killing three people and seriously wounding eight others. An investigation ensued and six soldiers were indicted for murder. John Adams, a lawyer in Boston at the time (and later the second President of the United States), served as their defense.

The real battle took place in the newspapers after the event, where both sides attempted to depict it in a way that would benefit their cause. Rebellious colonists used this as an example of British tyranny and chose the name “massacre” to exaggerate the brutality of the British administration. Loyalists, on the other hand, used it as an example to show the radical nature of those protesting the king and how they stood to disrupt peace in the colonies. Loyalists, also called Tories or Royalists, were American colonists who supported the British monarchy during the American Revolutionary War.

In the end, the radicals won the hearts of the public, and the Boston Massacre became an important rallying point for the movement for American independence, which, in 1770, was just beginning to grow legs. The American Revolution was rearing it’s head.

The Tea Act

The growing discontent within the colonies about the taxes and laws surrounding trade continued to fall on deaf ears, and the British Parliament, drawing upon their immense creativity and compassion, reacted by imposing even more taxes on their New World neighbors. If you’re thinking, ‘What? Seriously?!’ just imagine how the colonists felt!

The next major act was the Tea Act of 1773, which was passed in an attempt to help improve the profitability of the British East India Company. Interestingly, the act did not impose any new taxes on the colonies but rather granted the British East India Company a monopoly on the tea sold within them. It also waived the taxes on the Company’s tea, which meant it could be sold for a reduced rate in the colonies as compared to tea imported by other merchants.

This enraged the colonists because it once again interfered with their ability to do business, and because, once again, the law had been passed without consulting the colonists to see how it would affect them. But this time, instead of writing letters and boycotting, the increasingly radical rebels took drastic action.

The first move was to block the unloading of tea. In Baltimore and Philadelphia, the ships were denied entry into the port and sent back to England, and in other ports, the tea was unloaded and left to rot on the dock.

In Boston, the ships were denied entry to the port, but the governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, in an attempt to enforce British law, ordered the ships to not go back to England. This left them stranded in the harbor, vulnerable to attack.

North Carolina responded to the Tea Act of 1773 by creating and enforcing non-importation agreements that forced merchants to drop trade with Britain. In the following year, when Massachusetts was punished by Parliament for the destruction of a shipload of tea in Boston Harbor, sympathetic North Carolinians sent food and other supplies to its beleaguered northern neighbor.

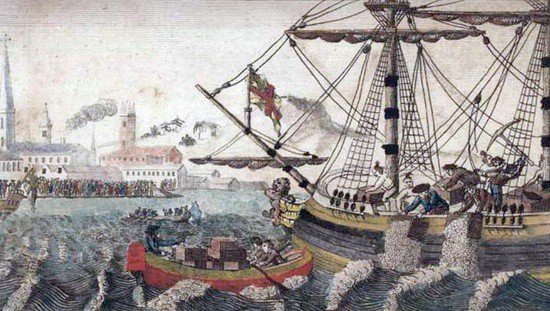

The Boston Tea Party

To send a message loud and clear to the British government that the Tea Act and all this other taxation without representation nonsense would not be tolerated, the Sons of Liberty, led by Samuel Adams, executed one of the more famous mass protests of all time.

They organized themselves and dressed up as Native Americans, sneaked into Boston harbor on the night of December 6, 1773, boarded the ships of the British East India Company, and dumped 340 chests of tea into the sea, the estimated value of which is about $1.7 million in today’s money.

This dramatic move absolutely infuriated the British government. The colonists had quite literally just dumped years worth of tea into the ocean — something that was celebrated by people around the colonies as a valiant act of defiance in the face of the repeated abuse dealt to them by Parliament and the king.

The event did not get the name “Boston Tea Party” until the 1820s, but it instantly became an important part of the American identity. To this day, it still remains a key part of the story that is told about the American Revolution and the rebellious spirit of 18th-century colonists.

In 21st century America, right-wing populists have used the name “Tea Party” to name a movement they claim seeks to restore the ideals of the American Revolution. This represents a rather romantic version of the past, but it speaks to how present the Boston Tea Party still is in today’s collective American identity.

In the course of England’s long and failed attempt to suppress the American Revolution the myth arose that its government had acted in haste. Accusations passed on at the time held that the nation’s political leaders had failed to understand the gravity of the challenge. In actual sense, the British cabinet first considered resorting to military might as early as January 1774, when word of the Boston Tea Party reached London.

The Coercive Acts

In keeping with tradition, the British government reacted harshly to the destruction of so much property and this blatant defiance of British law; the response coming in the form of the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts.

This series of laws was meant to directly punish the people of Boston for their insurrection and to intimidate them into accepting the power of Parliament. But all it did was poke the beast and encourage more sentiment for the American Revolution, not only in Boston but in the rest of the colonies as well.

The Coercive Acts consisted of the following laws:

- The Boston Port Act closed the port of Boston until the damage done during the Tea Party was repaid and restored. This move had a crippling effect on the Massachusetts economy and punished all people of the colony, not just those who had been responsible for the tea’s destruction, something North American colonists saw as harsh and unfair.

- The Massachusetts Government Act removed the colony’s right to elect its local officials, meaning they would be chosen by the governor. It also banned the colony’s Committee of Correspondence, although it continued to function in secret.

- The Administration of Justice Act allowed the governor of Massachusetts to move the trials of British officials to other colonies or even back to England. This was an attempt to ensure a fair trial, since Parliament could not trust the North American colonists to provide one for British officials. However, the colonists widely interpreted this as a way of protecting British officials who abused their power.

- The Quartering Act required Boston residents to open their homes and house British soldiers, which was just straight up intrusive and not cool.

- The Quebec Act expanded the boundaries of Quebec in an attempt to increase loyalty to the Crown as New England became more and more rebellious.

Totally not surprising that all these acts did was enrage the people of New England even more. Their creation also urged the rest of the colonies into action as they saw Parliament’s response as heavy-handed, and it showed them how few plans Parliament had for honoring the rights they felt they deserved as British subjects.

In Massachusetts, patriots wrote the “Suffolk Resolves” and formed the Provincial Congress, which began organizing and training militias in the event they would need to take up arms.

Also in 1774, each colony sent delegates to participate in the First Continental Congress. The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from a number of American colonies at the height of the American Revolution, who acted collectively for the people of the Thirteen Colonies that eventually became the United States of America. the First Continental Congress sought to help repair the broken relationship between the British government and its American colonies while also asserting the rights of colonists. North Carolina Royal Governor Josiah Martin opposed his colony’s participation in the First Continental Congress. However, local delegates met at New Bern and adopted a resolution that opposed all Parliamentary taxation in the American colonies and, in direct defiance of the governor, elected delegates to the Congress. The First Continental Congress passed and signed the Continental Association in its Declaration and Resolves, which called for a boycott of British goods to take effect in December 1774. It requested that local Committees of Safety enforce the boycott and regulate local prices for goods.

The Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, proclaiming that the 13 colonies were now independent sovereign states, devoid of British influence.

During this meeting, delegates debated how to respond to the British. In the end, they decided to impose a colony-wide boycott of all British goods starting in December of 1774. This did nothing to cool tensions, and within months, fighting would begin.

Latest US History Articles

Who Invented the Assembly Line? Henry Ford and the History of the Assembly Line

Who Invented the Cotton Gin? Eli Whitney and Cotton Gin Impact on America

The Most Famous Outlaws of the Wild West: Jesse James to Robert Leroy Parker

The American Revolution Begins

For more than a decade before the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, tensions had been building between North American colonists and the British authorities. The British authority had time and again shown it had no respect for the colonies as British subjects, and the colonists were a powder keg about to explode.

Protests continued throughout the winter, and in February 1775, Massachusetts was declared to be in an open state of rebellion. The government issued arrest warrants for key patriots such as Samuel Adams and John Hancock, but they had no intention of going quietly. What followed were the events that finally pushed the American forces over the edge and into war.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord

The first battle of the American Revolution took place in Lexington, Massachusetts on April 19, 1776. It began with what we now know as “Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride.” Although the details of this have been exaggerated over the years, much of the legend is true.

Revere rode through the night to warn Sam Adams and John Hancock, who were staying in Lexington at the time, that British troops were coming (‘The Redcoats are coming! The Redcoats are coming!’) to arrest them. He was joined by two other riders, also intending to ride to Concord, Massachusetts to ensure a store of weapons and ammunition had been hidden and dispersed, while British troops planned on capturing these supplies at the same time.

Revere was eventually captured, but he managed to get word to his fellow patriots. The citizens of Lexington, who had been training as part of a militia since the year before, organized and stood their ground on the Lexington Town Green. Someone — from which side no one is sure — fired the “shot heard ‘round the world” and the fighting began. It signaled the start of the American Revolution and led to the creation of a new nation. The outnumbered American forces were quickly dispersed, but word of their bravery made it to the many towns between Lexington and Concord.

Militias then organized and ambushed the British troops on the road to Concord, inflicting heavy damages and even killing several officers. The force had no choice but to retreat and abandon their march, assuring American victory at what we now call the Battle of Concord.

More Hostilities

Shortly after, the Massachusetts militias turned on Boston and drove royal officials out. Once they had taken control of the city, they established the Provincial Congress as the official government of Massachusetts. The Patriots, led by Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, as well as Benedict Arnold, also managed to capture Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, a huge moral victory that demonstrated support for the rebellion outside Massachusetts.

The British responded by attacking Boston on June 17, 1775, at Breed’s Hill, a battle now known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. This time, the British troops managed to secure a victory, driving the Patriots from Boston and retaking the city. But the Patriots managed to inflict heavy losses on their enemies, giving hope to the rebel cause.

During this summer, the Patriots attempted to invade and capture British North America (Canada) and failed miserably, though this defeat did not deter the colonists who now saw American independence on the horizon. Those in favor of independence began speaking more passionately about the topic and finding an audience. It was during this time that Thomas Paine’s forty-nine page pamphlet, “Common Sense,” made it onto the colonial streets, and people ate it up faster than the new release of a Harry Potter book. Rebellion was in the air, and the people were ready to fight.

The Declaration of Independence

In March of 1776, the Patriots, under the leadership of George Washington, marched into Boston and retook the city. By this point, the colonies had already begun the process of creating new state charters and discussing the terms of independence.

The Continental Congress provided guidance during the American Revolution and drafted the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.Thomas Jefferson was the primary author, and when he presented his document to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, it was passed with a majority and the United States was born. The Declaration of Independence argued for government by consent of the governed on the authority of the people of the thirteen colonies as “one people”, along with a long list indicting George III as violating English rights.

Of course, just declaring American independence from Britain wasn’t going to be enough. The colonies were still an important source of income for the Crown and Parliament, and losing a huge chunk of its overseas empire would have dealt a major blow to Great Britain’s great ego. There was plenty of fighting still to come.

The American Revolution in the North

In the beginning, the American Revolution appeared to be one of the biggest mismatches in history. The British Empire was one of the largest in the world, and it was held together with an army that was among the strongest and most well-organized on the planet. The Rebels, on the other hand, were not much more than a fiery band of misfits ticked off about having to pay taxes to their overbearing oppressors. When the guns fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775, there was not yet even a Continental Army.

As a result, one of the first things Congress did after declaring independence was create the Continental Army and name George Washington as the Commander. The United States’ first settlers adopted the British militia system, which required all able-bodied men between 16 and 60 to bear arms. Some 100,000 men served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. The infantry regiment was the single most distinguishable unit throughout the course of the Revolutionary War. While brigades and divisions were used to group units into a larger cohesive army, regiments were far and away the primary fighting force of the Revolutionary War.

Though the tactics utilized during the American Revolutionary War may seem rather obsolete today, the unreliability of the smoothbore muskets, usually only accurate out to about 50 yards or so, required close range and proximity to the enemy. As a result, discipline and shock were the trademark of this style of combat, with concentrated fire and bayonet charges deciding the outcome of a battle.

On July 3, 1775, George Washington rode out in front of the American troops gathered at Cambridge common in Massachusetts and drew his sword, formally taking command of the Continental Army.

But just saying you have an army doesn’t mean you actually do, and this soon showed. Despite this, the resilience of the Rebels paid off and won them some key victories in the early part of the American Revolutionary war, making it possible for the independence movement to stay alive.

The Revolutionary War in New York and New Jersey

Facing off against British forces at New York City, Washington realized that he needed advance information to deal with disciplined British regular troops. On August 12, 1776, Thomas Knowlton was given orders to form an elite group for reconnaissance and secret missions. He later became the head of the Knowlton Rangers, the army’s premier intelligence unit.

On August 27, 1776, the first official battle of the American Revolution, the Battle of Long Island, took place in Brooklyn, New York, and it was a decisive victory for the British. New York fell to the Crown and George Washington was forced to retreat from the city with the American forces. Washington’s army escaped across the East River in dozens of small riverboats to New York City on Manhattan Island. Once Washington was driven out of New York, he realized that he would need more than military might and amateur spies to defeat the British forces and made efforts to professionalize military intelligence with the aid of a man called Benjamin Tallmadge.

They created the Culper spy ring. A group of six spymasters whose achievements included exposing Benedict Arnold’s treasonous plans to capture West Point, along with his collaborator John André, Britain’s head spymaster and later they intercepted and deciphered coded messages between Cornwallis and Clinton during the Siege of Yorktown, leading to Cornwallis’s surrender.

Later that year, though, Washington struck back by crossing the Delaware River on Christmas Eve, 1776, to surprise a group of British soldiers stationed in Trenton, New Jersey, (riding gallantly at the bow of his riverboat exactly as depicted in one of the most famous paintings of the revolution). He defeated them handedly, or, as some would put it, badly, and then followed up his victory with another one at Princeton on January 3, 1777. The British strategy in 1777 involved two main prongs of attack aimed at separating New England (where the rebellion enjoyed the most popular support) from the other colonies.

These victories were small potatoes in the overall war effort, but they showed that the Patriots could beat the British, which gave the Rebels a big morale boost at a time when many were feeling they’d bit off more than they could chew.

The first major American victory came the following fall in Saratoga, in Northern New York. The British sent an army south from British North America (Canada) that was supposed to meet with another army moving north from New York. But, the British commander in New York, Wiliam Howe, had his phone turned off and missed the memo.

As a result, American forces at Saratoga, New York, led by still-rebellious Benedict Arnold, defeated the British forces and forced them to surrender. This American victory was significant as it was the first time the they had beaten the British into submission this way, and this encouraged France, who had been a behind-the-curtains ally at this point, to come out on-stage in full support of the American cause.

Washington entered his winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, on January 6, though a prolonged attrition conflict continued. Howe made no attempt to attack, much to Washington’s consternation.

The British attempted to fight back up north, but they could never make significant progress against the American forces, though the Patriots themselves found that they couldn’t advance on the British either. 1778 brought a major change in British strategy, the campaign to the north had essentially reached a stalemate, and to try and win the American Revolutionary war, British forces began focusing on the Southern colonies, which they perceived to be more loyal to the Crown and therefore easier to beat. The British grew increasingly frustrated. The loss at Saratoga, New York, was embarrassing. Capturing the enemy’s capital, Philadelphia, did not bring them much advantage. As long as the American Continental Army and state militias remained in the field, British forces had to keep on fighting.

The American Revolution in the South

In the South, Patriots benefitted from early victories at Fort Sullivan and Moore’s Creek. After the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey, the war in the North stalemated into raids, and the main Continental Army watched the British army in New York City. By 1778, the French, Spanish, and Dutch — all interested in seeing the downfall of the British in the Americas — had decided to officially team up against Great Britain and help the Patriots. The French-American Alliance, made official by treaty in 1778, proved to be the most significant to the war effort.

They contributed money, and definitely more importantly, a navy, as well as experienced military personnel who could help organize the ragtag Continental Army and turn it into a fighting force capable of defeating the British.

Several of these individuals, such as Marquis de Lafayette, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, and Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, to name a few, wound up being Revolutionary war heroes without which the Patriots may never have survived.

On December 19, 1778, Washington’s Continental Army entered the winter quarters at Valley Forge. Poor conditions and supply problems there resulted in the deaths of some 2,500 American troops. During Washington’s winter encampment at Valley Forge, Baron von Steuben – a Prussian who later became an American military officer and served as Inspector General and a Major General of the Continental Army -, introduced the latest Prussian methods of drilling and infantry tactics to the entire Continental Army. For the first three years until after Valley Forge, the Continental Army was largely supplemented by local state militias. At Washington’s discretion, the inexperienced officers and untrained troops were employed in attrition warfare rather than resorting to frontal assaults against Britain’s professional army.

The British Push South

The decision by British commanders to move the Revolutionary war to the South appeared to be a smart one at first. They laid siege to Savannah, Georgia and captured it in 1778, managing to win a series of smaller battles throughout 1779. At this point, the Continental Congress was struggling to pay its soldiers, and morale was dipping, leaving many to wonder if they had not made the biggest mistake of their free lives.

But considering surrender likely would have turned the thousands of Patriots fighting for independence into traitors, who could be sentenced to death. Few people, especially those leading the fight, gave serious consideration to abandoning the cause. This steadfast commitment continued even after British troops won more decisive victories — first at the Battle of Camden and later with the Capture of Charleston, South Carolina — and it paid off in 1780 when the Rebels managed to win a series of smaller victories throughout the South that reinvigorated the Revolutionary war effort.

Before the Revolution, South Carolina had been starkly divided between the backcountry, which harbored revolutionary partisans, and the coastal regions, where Loyalists remained a powerful force. The Revolution provided an opportunity for residents to fight over their local resentments and antagonisms with murderous consequences. Revenge killings and the destruction of property became mainstays in the savage civil war that gripped the South.

Prior to the war in the Carolinas, South Carolina had sent sent wealthy rice planter Thomas Lynch, lawyer John Rutledge, and Christopher Gadsden (the man who came up with the ‘Don’t tread on me’ flag) to the Stamp Act Congress. Gadsden led the opposition and although Britain removed the taxes on everything except tea, Charlestonians mirrored the Boston Tea Party by dumping a shipment of tea into the Cooper River. Other shipments were allowed to land, but they rotted in Charles Town storehouses.

American victory at the Battle of King’s Mountain in South Carolina ended British hopes of invading North Carolina, and successes at the Battle of Cowpens, the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, and the Battle of Eutaw Springs, all in 1781, sent the British army under the command of Lord Cornwallis on the run, and it gave the Patriots their chance to deliver a knockout blow. Another British mistake was burning the Stateburg, South Carolina, home and harassing the incapacitated wife of a then inconsequential colonel named Thomas Sumter. Because of his fury over this, Sumter became one of the fiercest and most devastating guerrilla leaders of the war, becoming known as “The Gamecock”.

Throughout the course of the American Revolutionary War, over 200 battles were fought within South Carolina, more than in any other state. South Carolina had one of the strongest Loyalists factions of any state. About 5000 men took up arms against the United States government during the revolution, and thousands more were supporters who avoided taxes, sold supplies to the British, and who had avoided conscription.

The Battle of Yorktown

After suffering a string of defeats in the South, Lord Cornwallis began moving his army north into Virginia, where he was trailed by a coalition army of Patriots and French led by the Marquis de Lafayette.

The British had dispatched a fleet from New York under Thomas Graves to rendezvous with Cornwallis. As they approached the entry to the Chesapeake Bay on September, French warships engaged the British in what came to be known as the Battle of the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781, and forced British troops to retreat. The French fleet then sailed south to blockade the port of Yorktown, where they met the Continental Army.

At this point, the force led by Cornwallis was completely surrounded by both land and sea. The American-French army laid siege to Yorktown for several weeks, but despite their fervor didn’t manage to inflict much damage, as neither side was willing to engage. After nearly three weeks of siege, Cornwallis remained thoroughly surrounded on all sides, and when he learned that General Howe would not be coming down from New York with more troops, he figured all that was left for him there was death. So, he made the very wise yet humiliating choice to surrender.

Prior to the surrender of British Army General Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown, King George III still had hoped for victory in the South. He believed a majority of American colonists supported him, especially in the South and among thousands of black slaves. But after Valley Forge, the Continental Army was an efficient fighting force. After a two-week siege at Yorktown by Washington’s army, a successful French fleet, French regulars and local reinforcements, the British troops surrendered on October 19, 1781

This was checkmate for the American forces. The British had no other major army in America, and continuing the Revolutionary war would have been costly and likely unproductive. As a result, after Cornwallis surrendered his army, the two sides began negotiating a peace treaty to bring an end to the American Revolution. The British troops remaining in America were garrisoned in the three port cities of New York, Charleston, and Savannah.

The American Revolution Ends: Peace and Independence

After American victory at Yorktown, everything changed in the story of the American Revolution. The British administration switched hands from the Tories to the Whigs, two of the dominant political parties at the time, and the Whigs — who had traditionally been more sympathetic to the American cause — encouraged more aggressive peace negotiations, which took place almost immediately with the American envoys living in Paris.

Once the Revolutionary war was lost, some in Britain argued that it had been unwinnable. For generals and admirals who were defending their reputations, and for patriots who found it painful to acknowledge defeat, the concept of foreordained failure was alluring. Nothing could have been done, or so the argument went, to have altered the outcome. Lord Frederick North, who led Great Britain through most of the American Revolutionary War, was condemned, not for having lost the war, but for having led his country into a conflict in which victory was impossible.

The US sought full independence from Great Britain, clear boundaries, a repeal of the Quebec Act, and rights to fish the Grand Banks off British North America (Canada), along with several other terms that were ultimately not included in the peace treaty.

Most terms were set between the British and the Americans by November 1782, but since the American Revolution was technically fought between the British and the Americans/French/Spanish, the British would not and could not agree to peace terms until they’d signed treaties with the French and the Spanish.

The Spanish used this as an attempt to retain control over Gibraltar (something they continue to try to do to this day as a part of Brexit negotiations), but a failed military exercise forced them to abandon this plan.

Eventually, the French and Spanish both made peace with the British, and the Treaty of Paris was signed on January 20, 1783, two years after Cornwallis’ surrender a document which officially recognized the United States of America as a free and sovereign nation. And with that, the American Revolution finally came to a close.To an extent, the Revolutionary War had been undertaken by the Americans to avoid the costs of continued membership in the British Empire, the goal had been achieved. As an independent nation the United States was no longer subject to the regulations of the Navigation Acts. There was no longer to be any economic burden from British taxation.

There was also the issue of what to do with the British loyalists after the American Revolution. Why, the revolutionaries asked, should those who sacrificed so much for independence welcome back into their communities those who had fled, or worse, actively aided the British?

Despite the calls for punishment and rejection, the American Revolution—unlike so many revolutions throughout history—ended relatively peacefully. That achievement alone is something worthy of note. People got on with their lives, choosing at the end of the day to ignore past wrongs. The American Revolution created American national identity, a sense of community based on shared history and culture, mutual experience, and belief in a common destiny.

Remembering the American Revolution

The American Revolution has often been portrayed in patriotic terms in both Great Britain and the United States of America that gloss over its complexity. The Revolution was both an international conflict, with Britain and France vying on land and sea, and a civil war among the colonists, causing over 60,000 loyalists to flee their homes.

It’s been 243 years since the American Revolution, yet it is still alive today.

Not only are Americans still fiercely patriotic, but politicians and social movement leaders alike constantly evoke the words of the “Founding Fathers” when advocating for the defense of American ideals and values, something needed now more than ever. The American Revolution was a gradual change in popular thinking about the relation between ordinary people and government power.

It’s important to study the American Revolution and to look at it with a grain of salt — one example being the understanding that most independence leaders were largely wealthy, White property owners who stood to lose the most from British taxation and trade policies.

It is important to mention that George Washington lifted the ban on black enlistment in the Continental Army in January 1776, in response to a need to fill manpower shortages in America’s rookie army and navy. Many African Americans, believing that the Patriot cause would one day result in an expansion of their own civil rights and even the abolition of slavery, had already joined militia regiments at the beginning of the war.

Furthermore, independence did not mean freedom for the millions of African slaves who had been ripped from their homeland and sold into bondage in the Americas. African American slaves and freedmen fought on both sides of the American Revolutionary War; many were promised their freedom in exchange for service. As a matter of fact, Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in United States history. Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to all slaves who would fight for the British during the Revolutionary War. Hundreds of slaves escaped to join Dunmore and the British Army. The US Constitution, which went into effect in 1788, protected the international slave trade from being banned for at least 20 years.

South Carolina had also gone through bitter internal conflict between Patriots and Loyalists during the war. Nevertheless, it adopted a policy of reconciliation that proved more moderate than any other state. About 4500 white Loyalists left when the war ended, but the majority remained behind.

On several occasions, the U.S. military destroyed settlements and murdered American Indian captives. The most brutal example of this was the Gnadenhutten Massacre in 1782. Once the Revolutionary war ended in 1783, tensions continued to remain high between the United States and the region’s American Indians. Violence continued as settlers moved into the territory won from the British in the American Revolution.

Its also important to remember the role women played in the American Revolution. Women supported the American Revolution by making homespun cloth, working to produce goods and services to help the army, and even serving as spies and there is at least one documented case of a woman disguising herself as a man to fight in the Revolutionary war.

After the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the Daughters of Liberty was formed. Established in 1765, the organization was comprised solely of women who sought to demonstrate their loyalty to the American Revolution by boycotting British goods and making their own. Martha Washington, wife of George Washington, was one of the most prominent Daughters of Liberty.

This created a paradox in the American experiment: the founders sought to build a nation around the freedom of all, while simultaneously denying segments of the population fundamental human rights.

This behaviour seems appalling, but the way the United States operates today is not all that different. So while the United States of America’s origin story makes good theater, we must remember that the oppression and abuses of power that we’ve seen since before the birth of the country are still alive and well in 21st-century United States of America.

Nevertheless, the American Revolution sparked a new era in human history, one based on democratic and republican ideals. And although it took the United States more than a century to work through its growing pains and emerge as a prosperous country, once it hit the world stage, it took control like no other nation before it. The American Revolution committed the United States of America to ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship and made them the basis of a new political order.

The lessons offered by the British experience in the American Revolutionary War for modern military strategy and logistics planning and operations are numerous. Strategic lift of forces and supplies into the theater of operations remains the most immediate concern for a deploying army. Current U.S. military strategy is based on force projection, which often rests on the assumption that there will be sufficient time to build up supplies and combat power before hostilities begin. The British troops did not have sufficient time to build up supplies, given the limitations of their logistics organization, and British generals never felt that they had sufficient stores to campaign effectively against the rebels.

The American Revolution showed that revolutions could succeed and that ordinary people could govern themselves. Its ideas and examples inspired the French Revolution (1789) and later nationalist and independence movements. However, these ideals were put to test years later when the American Civil war erupted in 1861.

Today, we live in an era of American hegemony. And to think — it all began when Paul Revere and his good pals decided to take a midnight ride one quiet night, in April 1775.

READ MORE: The XYZ Affair

Explore More US History Articles

Pearl Harbor: A Day in Infamy

Battle of Guadalcanal: Significance, Location, Outcome, and More!

US History Timeline: The Dates of America’s Journey

“Without a Second’s Warning” The Heppner Flood of 1903

The 1948 Vanport Flood: A Personal Recollection

History of Florida: Early History, Exploration, Colonization, Becoming a State, and More!

Bibliography

| Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America. Knopf, 2014. Macksey, Piers. The War for America, 1775-1783. University of Nebraska Press, 1993. McCullough, David. 1776. Simon and Schuster, 2005. Morgan, Edmund S. The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89. University of Chicago Press, 2012. Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. WW Norton & Company, 2016. |