Medusa is a famous monster from Greek mythology. This fearsome creature with a head of snakes and the power to turn men to stone has been a recurring feature of popular fiction and, in modern consciousness, one of the staples of Greek myth.

But there is more to Medusa than her monstrous gaze. Her history – both as a character and an image – go much deeper than the classic depictions. So, let’s dare to look directly at the Medusa myth.

Table of Contents

Who is Medusa?

Medusa is a mythical creature from ancient Greek mythology. She is one of the Gorgons and is depicted as a monstrous female creature with wings and snakes for hair and the ability to turn anyone who looks at them into stone.

In ancient Greece, Medusa’s image was often used as a protective symbol. Her fearsome visage was thought to ward off evil and protect against danger.

She has also been a popular subject in art throughout history. Her image appears in various sculptures, paintings, and other forms of artwork, often depicting her as a terrifying and powerful figure.

The Origin of Medusa

Medusa was the daughter of the primordial sea deities Ceto and Phorcys, who were in turn the children of Gaia and Pontus. Among the oldest gods of Greek mythology, these sea gods preceded the more noted Poseidon and were each decidedly more monstrous in aspect (Phorcys was generally depicted as a fish-tailed being with crab claws, while Ceto’s name literally translates to “sea monster”).

Her siblings, without exception, were similarly monstrous – one of her sisters was Echidna, the half-woman, the half-serpent creature who was herself the mother of many of the most recognizable monsters in Greek mythology. Another sibling was the dragon Ladon, who guarded the golden apples ultimately taken by Heracles (though some sources make Ladon a child of Echidna, rather than Ceto and Phorcys). According to Homer, the dreaded Scylla was also one of Phorcys’ and Ceto’s children.

READ MORE: Snake Gods and Goddesses: 19 Serpent Deities from Around the World

The Sisters Three

Also among Medusa’s siblings were the Graeae, a trio of hideous sea hags. The Graeae – Enyo, Pemphredo, and (depending on the source) either Persis or Dino – were born with gray hair and shared only a single eye and a single tooth between the three of them (Perseus would later steal their eye, snatching it as they passed it amongst themselves, and holding it hostage in exchange for information that would help him kill their sister).

There are some accounts that describe the Graeae as being only a pair instead of a triplet. But there is a recurring theme of triads in Greek and Roman mythology, chiefly among gods but also among significant figures such as the Hesperides or the Fates. It’s unsurprising, therefore, that iconic figures like the Graeae would be made to conform to that theme.

Medusa herself was part of a similar triad with her remaining two siblings, Euryale and Stheno. These three daughters of Phorcys and Ceto formed the Gorgons, hideous creatures that could turn any who gazed upon them into stone – and who were perhaps some of the most ancient figures in Greek mythology.

The Gorgons

Long before they were connected to Ceto and Phorcys, the Gorgons were a popular feature in the literature and art of ancient Greece. Homer, somewhere between the 8th and 12th Centuries B.C.E., even made mention of them in the Iliad.

The name “Gorgon” translates roughly to “dreadful” and while that was universally true of them, the specific depictions of these early figures could vary substantially. Many times, they would show some connection to serpents, but not always in the obvious way associated with Medusa – some were shown with snakes for hair, but that wouldn’t be a common feature associated with Gorgons until about the 1st Century B.C.E.

And different versions of the Gorgons may or may not possess wings, beards, or tusks. The oldest depictions of these creatures – which extend back into the Bronze Age – could even be hermaphrodites or hybrids of humans and animals.

The only thing that was always true of Gorgons is that they were foul creatures that loathed mankind. This notion of Gorgons would remain constant for centuries, from Homer’s initial reference (and certainly much earlier than that) all the way through the Roman era when Ovid called them “harpies of foul wing.”

Unlike the norm for Greek art, a Gorgoneia (the depiction of a Gorgon’s face or head) generally faced the viewer directly, rather than being depicted in profile like other characters. They were a common decoration not just on vases and other conventional artworks but were frequently used in architecture as well, appearing prominently on some of the oldest structures in Greece.

Evolving Monsters

The Gorgoneia seemed to initially have no association with a specific being. Rather, it seems likely that Medusa and the other Gorgons evolved from the images of the Gorgoneia. The earliest references to the Gorgons even appear to describe them as mere heads, just terrifying visages without any recognizable, developed character attached.

This could make sense – there’s some suspicion that the Gorgoneia are holdovers of the early supplanting of an existing culture by the Hellenes. The terrifying faces of the Gorgons could represent ceremonial masks of ancient cults – it’s already been noted that many Gorgon depictions involved snakes in some fashion, and serpents were commonly associated with fertility.

It’s also worth noting that Medusa’s name seems to derive from the Greek word for “guardian,” reinforcing the notion that the Gorgoneia were protective totems. The fact that they constantly face directly outward in Greek artwork seems to support this idea.

This puts them in similar company as the Onigawara of Japan, fearsome grotesques which are commonly found on Buddhist temples, or the more familiar gargoyles of Europe which frequently adorn cathedrals. The fact that Gorgoneia were often a feature of the oldest religious sites implies a similar nature and function and lends credence to the idea that the Gorgons may have been a mythical character created from these relics of ancient fright-masks.

READ MORE: The History of Buddhism

First Among Equals

It’s also worth noting that the idea of three Gorgons may have been a later invention. Homer mentions only one Gorgon – it’s Hesiod in the 7th Century B.C.E. that introduces Euryale and Stheno – again, conforming myth to the culturally and spiritually significant concept of the triad.

And while the earlier stories of the three Gorgon sisters imagine them as terrifying from birth, that image shifts in favor of Medusa over time. In later accounts such as that found in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Medusa doesn’t start out as a hideous monster – rather, she begins the story as a beautiful maiden and one who, unlike the rest of her siblings and even her fellow Gorgons, was mortal.

Medusa’s Transformation

In these later stories, Medusa’s monstrous attributes come to her only later as the result of a curse by the goddess Athena. Apollodorus of Athens (a Greek historian and rough contemporary of Ovid) claims that Medusa’s transformation was a punishment both for Medusa’s beauty (which enthralled all those around her and even rivaled that of the goddess herself), and for her boastful vanity about it (plausible enough, given the petty jealousies for which the Greek gods were known).

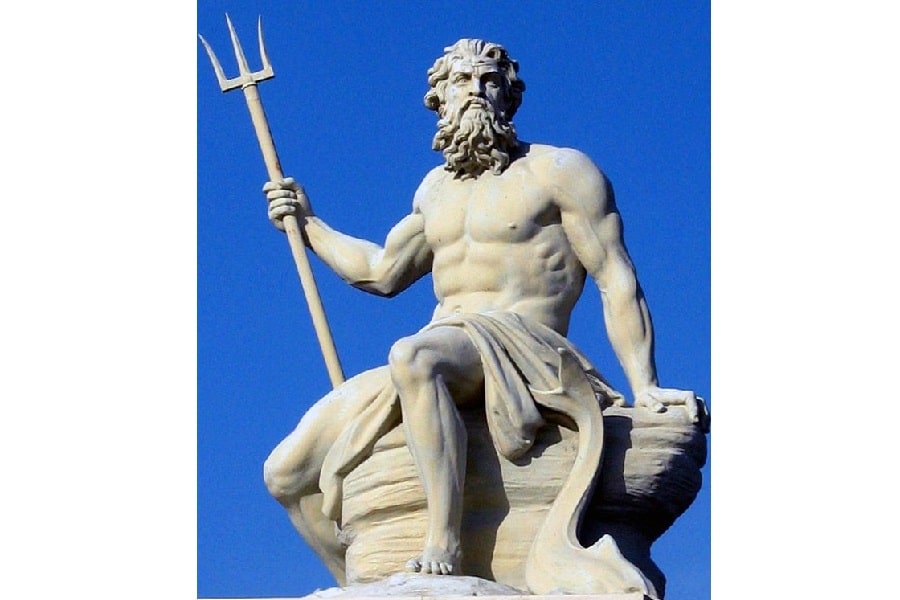

But most versions put the catalyst for Medusa’s curse as something more severe – and something for which Medusa herself may be blameless. In Ovid’s telling of Medusa’s story, she was renowned for her beauty and beset by many suitors, catching even the eye of the god Poseidon (or rather, his Roman equivalent, Neptune, in Ovid’s text).

Fleeing the lecherous god, Medusa takes refuge in the temple of Athena (a.k.a, Minerva). And while there are some claims that Medusa already resided in the temple and was in fact a priestess of Athena, this seems to be based on no original Greek or Roman source and is perhaps a much later invention.

Undeterred by the sacred place (and apparently unconcerned about aggravating his often-contentious relationship with his niece, Athena), Poseidon enters the temple, and either seduces or outright rapes Medusa (though a few sources suggest it was a consensual encounter, this seems a minority opinion). Scandalized by this lewd act (Ovid notes that the goddess “hid her chaste eyes behind her aegis “ to avoid looking upon Medusa and Poseidon) and furious at the desecration of her temple, Athena cursed Medusa with a terrifying form, replacing her long hair with foul snakes.

Unequal Justice

This story raises some sharp questions about Athena – and by extension, the gods in general. She and Poseidon were not on particularly good terms – the two had vied for control of the city of Athens, most notably – and clearly, Poseidon thought nothing of desecrating Athena’s holy place.

Why, then, did Athena’s anger seem to be directed solely at Medusa? Especially when, in almost all versions of the story, Poseidon had been the aggressor and Medusa the victim, why did Medusa pay the price while Poseidon seems to have escaped her wrath entirely?

Callous Gods

The answer may simply lie in the nature of the Greek gods and their relationship with mortals. There’s no shortage of incidents in Greek mythology that demonstrate humans being the gods’ playthings, including in their conflicts with each other.

For instance, in the aforementioned contest for the city of Athens, Athena and Poseidon each gave a gift to the city. The people of the city chose Athena based on the olive tree she provided, while Poseidon’s fountain of salt water – in a coastal city with plenty of seawater at hand – was less well received.

The sea god did not accept this loss well. Apollodorus, in Chapter 14 of his work Library, notes that Poseidon “in hot anger flooded the Thriasian plain and laid Attica under the sea.” This example of what must have been a wholesale slaughter of mortals in a fit of pique says everything one needs to know about how much value the gods place on their lives and welfare. Given how many similar stories one can find in Greek myth – not to mention the blatant favoritism and unfairness which the gods would dole out for sometimes the pettiest of reasons – and Athena’s taking out her anger on Medusa doesn’t seem out of place.

Above the Law

But that still leaves the question of why Poseidon escaped any retribution for the act. He was, after all, the instigator of the blasphemy, so why would Athena not mete out at least some token punishment to him?

The simple answer may be that Poseidon was powerful – the brother of Zeus, he would have rated as among the strongest of the Olympian gods. He brought storms and earthquakes and ruled the seas which Athens, like many coastal Greek cities, depended on for fishing and trade.

When the two had fought over control of Athens, it was Zeus that had stepped in with the idea of a contest to stop the two from fighting over it, fearing that such a struggle between the gods ruling the sky and sea would be unimaginably destructive. And given Poseidon’s established reputation for being temperamental, it’s easy to imagine that Athena felt cursing the object of his lust would be as much punishment as she could dispense without likely causing greater harm.

Perseus and the Medusa

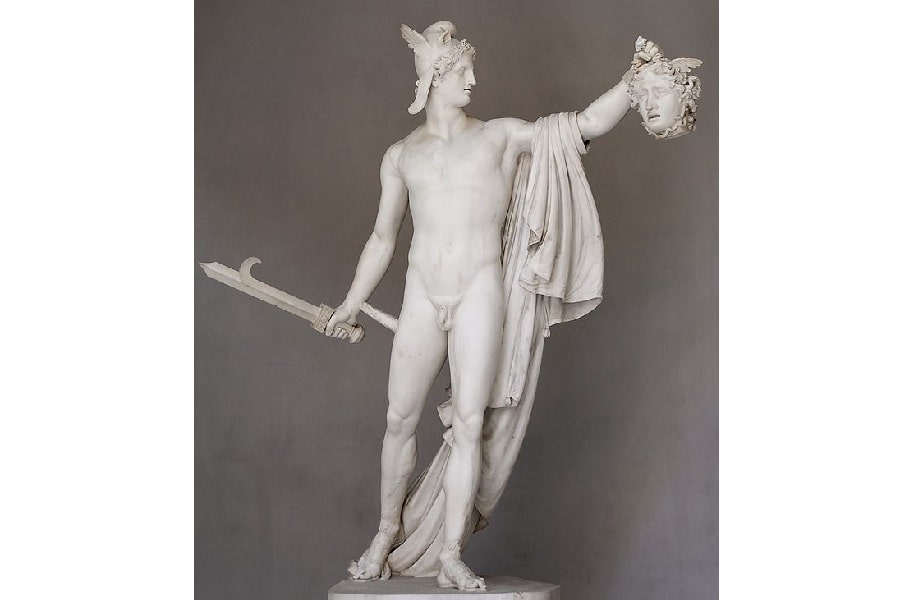

Medusa’s most famous and significant appearance as a mythological character involves her death and decapitation. This tale, like her backstory, originates in Hesiod’s Theogony and is later retold by Apollodorus in his Library.

But though it’s her only significant appearance – at least in her monstrous, post-curse form – she plays a little active role in it. Rather, her end is merely part of the story of her slayer, the Greek hero Perseus.

Who is Perseus?

Acrisius, king of Argos, was foretold in a prophecy that his daughter Danae would bear a son that would kill him. Seeking to prevent this, he locked his daughter away underground in a chamber of brass, safely quarantined from any potential suitors.

Unfortunately, there was one suitor the king could not keep out – Zeus himself. The god seduced Danae, coming to her as a trickle of golden liquid that seeped down from the roof and impregnated her with the prophesied son, Perseus.

Thrown to the Sea

When his daughter gave birth to a son, Acrisius became fearful that the prophecy would be fulfilled. He didn’t dare kill the child, however, for killing a son of Zeus would surely bring a heavy price.

Instead, Acrisius put the boy and his mother into a wooden chest and cast them into the sea, for fate to do with as it pleased. Adrift on the ocean, Danae prayed to Zeus for rescue, as described by the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos.

The chest would wash up on the shores of Seriphos, an island in the Aegean Sea ruled by King Polydectes. It was on this island that Perseus grew to manhood.

The Deadly Quest

Polydectes came to love Danae, but Perseus thought him untrustworthy and stood in the way. Eager to remove this obstacle, the king came up with a plan.

He held a great feast, with each guest expected to bring a horse as a gift – the king had claimed he was about to ask for the hand of Hippodamia of Pisa and needed the horses to present to her. Having no horses to give, Perseus asked what he might bring and Polydectes asked for the head of the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa. This quest, the king felt sure, was one from which Perseus would never return.

The Hero’s Journey

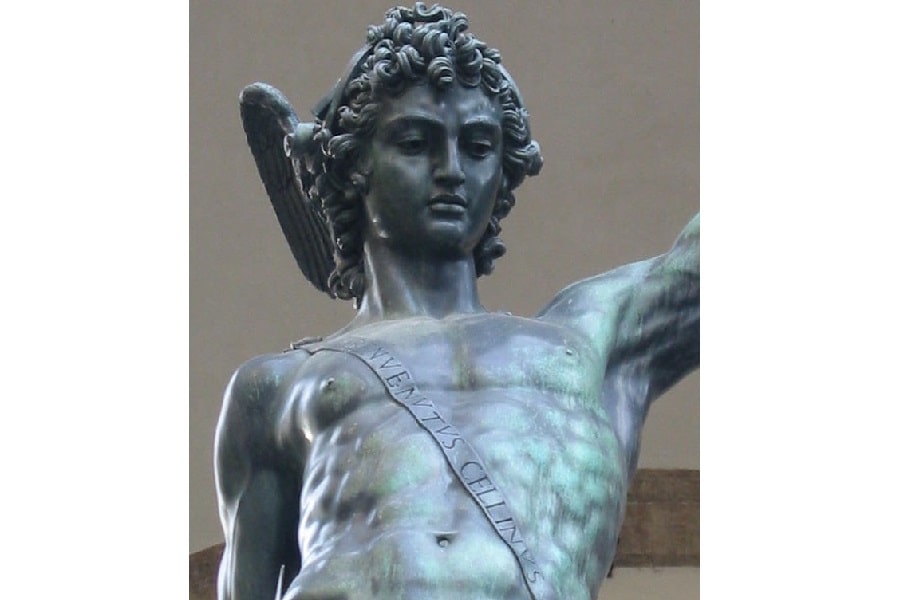

William Smith’s 1849 A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biology and Mythology is a landmark collection of both classic sources and later scholarship. And in this tome, we can find a synopsis of Perseus’ preparations to take on the Gorgon, under the guidance of both the god Hermes and the goddess Athena – the motive for the gods’ involvement is not known, though Athena’s prior connection to Medusa might play a part.

Perseus first sets off to find the Graeae, who kept the secret of where to find the Hesperides, who held the tools he would need. Unwilling to betray their Gorgon sisters, they at first refused to provide this information, until Perseus extorted them by snatching their single, shared eye as they were passing it between them. Once they told him what he needed, he either (depending on the source) returned the eye or threw it into Lake Triton, leaving them blind.

From the Hesperides, Perseus acquired various divine gifts to aid him on his quest – winged sandals which allowed him to fly, a bag (called a kibisis) that could safely contain the head of the Gorgon, and the Hades Helmet which rendered its wearer invisible.

Athena additionally lent him a polished shield, and Hermes gave him a sickle or sword made of adamantine (a form of a diamond). Thus armed, he traveled to the cave of the Gorgons, said to be somewhere near Tartessus (in modern-day southern Spain).

Slaying the Gorgon

While the classic depiction of Medusa gives her snakes for hair, Apollodorus describes the Gorgons Perseus encountered as having dragon-like scales covering their heads, along with boar tusks, golden wings, and hands of brass. Again, these are some of the classic variations of a Gorgoneia and would have been quite familiar to Apollodorus’ readers. Other sources, notably Ovid, give us the more familiar depiction of Medusa’s hair of venomous snakes.

The accounts of the actual slaying of Medusa generally agree that the Gorgon was asleep when Perseus came upon her – in some accounts, she is entangled with her immortal sisters, while in Hersiod’s version, she is actually laying with Poseidon himself (which might, again, explain Athena’s willingness to help).

Looking at Medusa only in the reflection on the mirrored shield, Perseus approached and decapitated the Gorgon, slipping it quickly into the kibisis. In some accounts, he was pursued by Medusa’s sisters, the two immortal Gorgons, but the hero escaped them by donning Hades’ helmet.

READ MORE: Hades: Greek God of the Underworld

Interestingly, there is an artwork by Polygnotus of Ethos from about the 5th Century B.C.E. which depicts the slaying of Medusa – but in a very unusual fashion. On a terracotta pelike or jar, Polygnotus shows Perseus about to decapitate the sleeping Medusa, but depicts her without monstrous features, simply as a beautiful maiden.

It’s hard to dismiss the idea that there was some message in this artistic license, some form of satire or commentary. But with valuable social and cultural context lost to the ages, it’s likely impossible for us to successfully decipher it now.

Medusa’s Offspring

Medusa died carrying two children fathered by Poseidon, who were birthed from her severed neck when she was slain by Perseus. The first was Pegasus, the familiar winged horse of Greek myth.

The second was Chrysaor, whose name means “He who has a golden sword,” described as seemingly a mortal man. He would marry one of the daughters of the Titan Oceanus, Callirrhoe, and two would produce the giant Geryon, later slain by Heracles (in some accounts, Chrysaor and Callirrhoe are also the parents of Echidna).

And Medusa’s Power

It’s worth noting that the terrifying power of the Gorgon to turn men and beasts to stone is not depicted when Medusa is alive. If this fate befell anyone before Perseus beheaded Medusa, it doesn’t appear in Greek myths. It is only as a severed head that Medusa’s fearsome power is displayed.

This again seems like a callback to the origins of the Gorgon, the Gorgoneia – a grotesque face that acted as a protective totem. As with Polygnotus’ artwork, we lack a cultural context that may have been much more evident to contemporary readers and imparted greater meaning to the severed head of Medusa which we no longer see.

As he flew home, Perseus traveled across Northern Africa. There he visited the Titan Atlas, who had refused him hospitality in fear of a prophecy that a son of Zeus would steal his golden apples (as Heracles – another son of Zeus and Perseus’ own great-grandson – would). Using the power of the Gorgon’s head, Perseus turned the Titan to stone, forming the mountain range today called the Atlas Mountains.

Flying over modern Libya with his winged sandals, Perseus inadvertently created a race of venomous snakes when drops of Medusa’s blood fell to earth, each one birthing a viper. These same vipers would later be encountered by the Argonauts and would kill the seer Mopsus.

The Rescue of Andromeda

The most famous use of Medusa’s power would come in modern-day Ethiopia, with the rescue of the beautiful princess Andromeda. Poseidon’s ire had been drawn by Queen Cassiopeia’s boast that her daughter’s beauty rivaled that of the Nereids, and as a consequence, he had flooded the city and sent a great sea monster, Cetus, against it.

An oracle had declared that the beast would be satisfied only if the king sacrificed his daughter by leaving her chained to a rock for the beast to take. Falling in love with the princess on sight, Perseus used Medusa’s head against Cetos in return for the king’s promise of Andromeda’s hand in marriage.

Journey’s End and Medusa’s Fate

Now married, Perseus arrived home with his new wife. Fulfilling Polydectes’ request, he presented him with Medusa’s head, turning the king to stone in the process and freeing his mother from his lustful designs.

He returned the divine gifts he’d been given for his quest, and then Perseus gave Medusa’s head to Athena. The goddess would then place the head upon her own shield – again returning Medusa to the Gorgoneia from which she seems to have evolved.

The image of Medusa would endure – Greek and Roman shields, breastplates, and other artifacts from as late as the 4th Century B.C.E. show that the Gorgon’s image was still being used as a protective amulet. And artifacts and architectural elements have been found everywhere from Turkey to the UK which suggests that the notion of Medusa as a protective guardian was embraced to some degree across the whole of the Roman Empire at its furthest expansion. Even today, her carved image adorns a rock off the coast of Matala, Crete – a guardian regarding all who pass with her terrifying gaze.