As the last of the apple blossoms were swept away by the groundskeepers, and the slight chill that had been in the Michigan air for over 6 months was finally gone, hundreds of young men scrambled this way and that, desperately trying to make it to their final exams.

A young man named James H. Kidd, possessed of entirely common features, and standing five feet, nine inches tall, and weighing about 140 pounds, with eyes that reflected both a light-hearted by solemn spirit, rushed among them.

Taking a shortcut through the square that formed the University of Michigan’s school of law, Kidd was caught off guard by the sound of hundreds of feet rapidly hitting the stone, causing a sound nearly akin to rapid gunfire, a sound which Kidd would soon find all too familiar.

Recommended Reading

Nathan Bedford Forrest: Life and Service of the Military Genius

The Right Arm of Custer: Colonel James H. Kidd

The Paradoxical President: Re-imagining Abraham Lincoln

Born in 1840, James H. Kidd was the eldest child of James M. Kidd and his wife, Jane Stevenson Kidd. Living a rather normal life in Ionia Michigan, James was an academic boy, and no one was surprised when he went off to a university at age 18.

Ending up at the University of Michigan after graduating from the Ypsilanti Union Seminary, Kidd enrolled in the classical course, the most popular majors at that time. This strenuous course included all of the classical literatures of western civilization, mathematics, and numerous foreign languages.

READ MORE: Who Invented Math? The History of Mathematics

Towards the end of Kidd’s junior year the Civil War broke out. Kidd decided to stay in school until he graduated, though a number of his friends marched off to war. In the meantime, Kidd joined the Tappan Guards, a militia unit consisting entirely of university students.

Kidd’s natural common sense and leadership ability quickly gained him the rank of second lieutenant. Here Kidd learned the basics of soldiering, and more importantly, of command. When President Lincoln called for 300,000 additional troops on July 2nd, 1862, Kidd was anxious to sign up.

Trying to join a prestigious mounted unit then forming, Kidd was turned away because the unit had reached its maximum number of men. Soon his father, an influential merchant and local politician, intervened, and with a letter to Congressman F. W. Kellogg, and secured a commission for young James along with authorization to raise a company of cavalry. Kidd wasted no time in forming his unit.

With great energy and ingenuity Kidd soon raised enough men, and on Tuesday, September 16th, the day before the bloodiest day in American history, one hundred and five strong Michigan men met in Ionia to take the oath of service to the United States government. From that day forward, they would be known as Company [E of the 6th Michigan Cavalry.

At the regimental rendezvous in Grand Rapids, the farmers, mechanics, merchants, and laborers learned their new trade, and when the regiment embarked a few months later on the train to Washington, they had become soldiers. Arriving in the nation’s capitol about the same time Burnside was smashing his army against Lee’s impenetrable wall 50 miles south, the Michigan men were amazed at the sights and sounds of such a large city, whose population had doubled, then doubled again in the last year.

They soon learned that they were to be brigaded together with other regiments from Michigan, the 5th and 7th Michigan Cavalry Regiments, which had both formed at the same time that the 6th mustered in. Later, the veteran 1 st Michigan Cavalry would be added to their ranks. Additionally, the men of the 5th and 6th were soon issued state-of-the-art Spencer Repeating rifles.

These seven- shot weapons could be loaded from the breach, and could fire more rounds than any gun carried at that time by any soldier, North or South. The Michigan men spent the next months drilling and parading, but seeing little action.

READ MORE: The History Guns

At this time, Brigadier General J. T. Copeland, formerly of the 5th Michigan Cavalry, became the commander of the brigade, which was part of General Casey’s Division, all under Maj. Gem Samuel P. Heintzelman, who commanded the Department of Washington. Kidd, with his regiment, made a number of fruitless raids into the neighboring area, where nothing was accomplished but the toughening of men and horses to the rigors of campaign.

At this time, Kidd admitted that the only way he was able to survive these hard marches was due to the bag of coffee he had received from home.

In June, after arriving back in Washington after another one of these fruitless raids, Kidd and his regiment were suddenly told to strike their tents and get ready to march. Lee’s army was on the move north, and Brig. Gen. Julius Stahels independent cavalry division, to which the Michigan cavalry brigade belonged, as ordered north in pursuit as part of the Army of the Potomac.

In a strenuous, but pleasant march, Kidd, with the Michigan Cavalry brigade, passed to the front of the Federal Army, and on Sunday, June 28th, 1863, Kidd, with the 5th and 6th Michigan Cavalry, all under General Copeland, moved into the quiet town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and received a true hero’s welcome from the townspeople.

That night Kidd commanded Companies E and H as they picketed the road to Cashtown. Little could any of those troopers imagine that in just a few days two-thirds of the Army of Northern Virginia would be swarming down that very road. The next day the regiments returned to Emmitsburg, and Kidd learned that some major changes had taken place.

First, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, General Joseph Hooker, had been replaced by 5th Corps commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the third man to command the Army of the Potomac in 1863. More importantly, however, General Stahel had been relieved, and in his place a fiery young brigadier general named Judson Kilpatrick had been assigned.

Along with Kilpatrick came two new brigade commanders in what was now known as the 3rd Division, the brilliant and capable Elon J. Farnsworth, and Monroe, Michigan native, George A. Custer, both of whom had just been promoted from Cavalry Corps commander General Alfred Pleasonton’s staff.

Under this new leadership, Kidd and the rest of the regiment set out find Stuart’s cavalry, and received their baptism of fire in the Battle of Hanover, Pennsylvania, fought on June 30, 1863. Here Kidd first saw his new brigade commander, and years after the war described that first impression: “An officer superbly mounted and who sat on his charger as if to the manor born.

Tall, lithe, active, muscular, straight as an Indian and as quick in his movements he was as fair as a school girl…” Kidd continued for at least two dozen lines describing his new commander, showing more than any words could the esteem he held the “Boy General” in. Through the subsequent days of fighting Kidd and his troopers would be in some of the toughest fighting, first on desperate field of Rummers farm, where the flower of the South wrecked itself on the lines of Gregg and Custer, and then through the hellish midnight fighting in a rainstorm at Monterey Pass, and all along the line of retreat of the shattered Army of Northern Virginia.

Finally finding the rebel army pinned against the Potomac River at Falling Waters, General Kilpatrick ordered an assault against the rebel lines. The Michigan Brigade bore the brunt of this attack, the brigade’s numbers dwindling, but still full of vigor and ferocity. Kidd was everywhere along his line, sometimes in the thickest of the fighting.

Latest Civil War Biographies

Ann Rutledge: Abraham Lincoln’s First True Love?

The Paradoxical President: Re-imagining Abraham Lincoln

The Right Arm of Custer: Colonel James H. Kidd

After dismounting and while directing the alignment of his company in a skirmish line, a bullet tore through Kidd’s foot, making what a Washington surgeon called “The prettiest wound I ever saw.” Kidd couldn’t walk, and was out of the fight. After being escorted to a field hospital, Kidd spent many agonizing days with other wounded men until finally being moved to Washington.

After recovering sufficiently, Kidd, along with Lieutenant C. E. Storrs, headed home to Michigan to recuperate. After three months, during which time Kidd was commissioned Major, and commander of the 6th Michigan cavalry, a promotion which Kidd’s natural modesty caused him to quickly pass over in his memoirs. Recovered, James Kidd returned to the war.

Arriving on the 12th of October at his camp, Kidd missed what he called “one of the most exciting, if not brilliant engagements of the war,” the Fourth Battle of Brandy Station. Here, Kidd met face to face with General Custer for the first time, and found him to be “a man who made a business out of his profession; who went about the work of fighting battles and winning victories, as a railroad superintendent goes about running trains.” Commanding his regiment in battle for the first time, Kidd felt an even greater burden of responsibility on his shoulders.

READ MORE: Who Invented the Railroad? Exploring the Fascinating History of Railroads

In the coming months Kidd led his regiment through the bitter fights whose names are lost to history, but will live on in the annals of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade forever. Names such as Buckland Mills, Mine Run, and the Dahlgren Raid will always be remembered as costly affairs to the blue-coated troopers who fought so desperately there.

During this time the Wolverines also began to receive new recruits, and through strenuous drill and discipline, these “fresh fish” were soon integrated into the four proud regiments that made up the brigade. Also during this time Kidd’s regiment, and the other regiments of the brigade began a long friendship with the 1 st Vermont Cavalry, a bond that grew so strong that soon that regiment was known as the “8th Michigan Cavalry.”

During Grant’s overland campaign of 1864, Kidds 6th Michigan, and the rest of the Michigan brigade would fight in some of the most costly battles of the war. At the Wilderness, the 6th Michigan held the right of the brigade’s line against three times its number for half an hour, and then took part in the counter attack that would have cleared the way for Generals Gibbon and Barlow of the 2nd corps to add their weight to Hancock’s attack.

Unfortunately, the infantrymen remained in their trenches. Again at Yellow Tavern on May 11, the Wolverines made a gallant charge, and one man of the 5th Michigan killed the fabled General Stuart with a long range shot, thus depriving the South of one of its greatest commanders. In early June Kidd learned that he had been promoted to full Colonel, and was now in official command of the regiment.

His first battle in the new rank would also be his toughest, Trevilian Station, fought June 11-12, 1864. The fight was tough and spirited all along the line. With cavalrymen fighting both on horseback and dismounted, and the two lines hopelessly intermixed at close quarters, combat was the rule of the day. Custer and his men found the flank and rear of the enemy, but then found themselves scattered and disorganized.

During a spirited charge down a road, Kidd found himself alone, a new thoroughbred horse having carried him further than any of his men. He was quickly surrounded and captured by the enemy, but was rescued by a spirited charge by one of his regiment’s squadrons, which liberated him just in time. Later, Kidd procured what was said to be “the finest horse in the 7th Georgia cavalry,” and would own that mount for many years to come.

Soon after the unsuccessful raid that culminated in the battle of Trevilian Station, Sheridan was given command of a new army being formed in the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan took with him two of his favorite divisions of cavalry, and along with another division, already operating in the valley, he made a corps of three divisions that would be led by Generals Wesley Merritt, William Averell, and James H. Wilson.

In a number of battles and skirmishes around Winchester and Shepherdstown, Kidd and the 6th distinguished themselves and were the victors of every field. On the eve of the final battle for Winchester, Kidd found himself terribly sick with Jaundice and went to Custer to get a pass for a few days of rest.

Custer refused his lieutenant, saying that he could not spare him in the coming fight, and the next day Kidd led his regiment gallantly in a charge on foot, until he collapsed upon reaching the enemy’s vacated lines. Returning to his senses, Kidd got back in his saddle, and was soon ravenously hungry, eating any food he could get from his men. He would say after the war, “the battle of Winchester cured my Jaundice.”

While leading his men in one of the final attacks of the day, a bullet took off a large chunk of skin on Kidd’s thigh, but the wound was not so severe as to take him out of the fight. More severe was a shell fragment that wounded his horse, taking it out of the war forever and giving it a wound it would carry until its dying day (in 1888.)

A few days later, Kidd and his regiment participated in the great battle at Cedar Creek, but the regiment and most of the other commands in the cavalry corps sat as spectators to the battle until evening, when a great cavalry charge swept the enemy off the field, and bagged the Michigan men nearly as many prisoners as they had in the ranks.

After these costly fights Custer was promoted to division command and given command of the 3rd Division, of which the Michigan Brigade was not a part. This caused much sorrow in the ranks of the Wolverines, as they were each parting with a dear friend.

To fill Custer’s vacancy, his senior regimental commander, James Kidd, was promoted to command of the entire brigade. Kidd would serve as brigade commander until a permanent replacement was found a few months later. The winter months of 1864-1865 were spent in Winchester on court martial duty, a job Kidd detested.

Kidd spent the last days of the war in Winchester, though he tried nearly half a dozen times to get assigned back to the field. Arriving in Richmond a few days after Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Kidd wasted no time in making friends with the men who had been enemies just weeks before.

Kidd also accompanied the cavalrymen that accepted the surrender of John S. Mosby and his partisan rangers. Here the wartime story of most of the soldiers, north and south would have ended, but not for James Kidd and the Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Only a month after hostilities ended the Michigan Cavalry Brigade was sent west to become part of the Powder River expedition.

At a time when most men were finally resting in their own beds after four years of war, the Wolverines were out on terrible marches through blistering weather in chase of an invisible foe. Thankfully, in 1866 their enlistments expired, and the 6th Michigan Cavalry went home. By this time all the parades were over and all of the celebrations had stopped.

James H. Kidd was discharged from service on November 7th, 1865, 8 months after the war had ended. He started for home the week before Christmas, the young cavalryman finally laid down his sword.

After the war Kidd dabbled in many different hobbies and professions. Always a restless spirit, Kidd became a member of countless veterans’ organizations, gentleman’s clubs, a baseball team, and even joined the Michigan National Guard, in which he attained high rank.

Explore More US History Articles

Chicano Movement: Young Mexican Americans Seeking Change

Leisler’s Rebellion: A Scandalous Minister in a Divided Community 1689-1691

Pyramids in America: North, Central, and South American Monuments

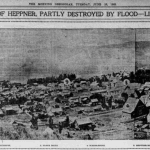

“Without a Second’s Warning” The Heppner Flood of 1903

The American Civil War: Dates, Causes, and People

Who Invented the Assembly Line? Henry Ford and the History of the Assembly Line

One of Kidd’s most important accomplishments was the realization of the dream he had carried with him for years. In 1887 Kidd became the owner and editor-in-chief of the Ionia Sentinel, where for years he put his gift for the written word on paper.

During this time Kidd also wrote a memoir, the “Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman with Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade in the Civil War.” This memoir should definitely be ranked among the greatest of all that came from the veterans of the Civil War.

On March 19th, 1913, the loyal cavalryman died at the age of 73. The guns had been silent for nearly 50 years, but James H. Kidd was only now finally at rest.

By Dan Waumbaugh