Huitzilopochtli was a significant deity in Aztec mythology and religion. He was one of their principal gods and held a central role in their religious beliefs and practices.

Worshiped as the god of war, Huitzilopochtli was associated with conquest and military prowess, and the Aztecs believed that through his favor, they would succeed in battles and maintain their dominance over other city-states and tribes in the region.

Table of Contents

Who is Huitzilopochtli?

Huitzilopochtli was a major deity in the Aztec pantheon. Of all the Aztec gods, he was considered the most powerful simply because he controlled the most important elements in life.

Huitzilopochtli was also considered the patron god of Tenochtitlan, the capital city for all the Aztecs and one that holds much importance in the pages of history.

The reasons behind his dominance over the Aztec people were much justified. He is deeply rooted in the foundations of the empire, culture, and the very core of their faith.

Myths featuring him (among other Aztec gods) generally include the Codex Zumarraga, Codex Florentine, Codex Ramirez, and the Codex Azcatitlan.

What is Huitzilopochtli the God Of?

Huitzilopochtli, also known as the “Hummingbird” or “The Turquoise Prince,” was the primary sun god in Aztec tales, but his powers also tethered him to war, fury, stars, and human sacrifices.

Since the Aztecs believed him to be such an important symbol of defense due to his origin myth, he is also one of the few making sure that life continues to persist for the Aztec empire.

As a result, he needed to be constantly nourished and invoked through whatever means necessary.

Who is the Strongest Aztec God?

It is, without a doubt, Huitzilopochtli. He is beyond all other Aztec gods, simply due to his flashy roles in keeping the empire alive. He is the sun itself, after all.

He is considered the strongest because his only weakness is that he needs to be replenished every 52 years. Besides this, the hummingbird remains dominant across the universe in perpetuity, defending the Aztec empire from their celestial enemies, come hell or high water. Plus, he doesn’t like to laze around; he is here for business.

Almost all of Huitzilopochtli’s lifetime is about chasing away his 400 siblings (the stars in the sky) and existing defensively in the thin line between looming darkness and eternal night.

In fact, the Aztecs believed that the day Huitzilopochtli fell would be the day the empire would end.

And that belief was held so strongly amongst the people that they were ready to do anything to appease their sun god, including the “art” of human sacrifice.

Why is Huitzilopochtli Important to the Aztecs?

The fall of Huitzilopochtli would spell doom for the Aztec empire.

In the minds of the believers, this statement was more than enough for them to ensure Huitzilopochtli remained nourished throughout his battle against evil.

On top of this, it was because of him that life existed. Without his heat and light, everything would be shrouded in obscurity. Without his blessings, the Aztecs would lose in every war, and fallen warriors would crumble in shame, having done nothing for their empire.

And that is exactly why Huitzilopochtli was so important to his people and the strongest god in the Aztec pantheon; he was the meaning of life.

In the Name: What Does Huitzilopochtli Mean?

The name of any Aztec god is a double-edged sword.

They are almost always hard to pronounce, but it’s super interesting to dive deep into their names and come up with their origins. In Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli is known as the “Southern Hummingbird,”; a name that may sound cute and cuddly, but make no mistake, this god is no pushover.

The hummingbird aspect of his name is derived from the Nahuatl words “huitzilin,” meaning hummingbird, and “opochtli,” meaning left or south. This makes sense as hummingbirds were fierce warriors in the Aztecs’ eyes, and the south symbolized warmth and light.

Meet the Family

Huitzilopochtli’s family is quite a colorful bunch. His mother, Coatlicue, was a goddess of fertility and the earth, known for her serpent skirt (don’t judge ancient fashion). His father, Mixcoatl, was a god of hunting and the Milky Way.

According to the Codex Zumarraga, his siblings are thought to be Quetzalcoatl, the god of Wisdom, Xipe-Totec, the god of Spring, and Tezcatlipoca, the deity overlooking the night sky and storms.

But hold on to your hats because Huitzilopochtli’s family drama doesn’t end there. He also had a sister named Coyolxauhqui, a moon goddess and definitely not his biggest fan. In fact, their sibling rivalry reached epic proportions.

Is Huitzilopochtli Evil?

Ah, the million-dollar question.

In the Aztec world, Huitzilopochtli was seen as a protector and a vital force for life. Sure, he demanded human sacrifices to keep the sun shining, but you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, right?

The Aztecs believed his role in maintaining the delicate balance of life and death was essential. So, while he might seem a little… intense, he’s not all bad – just a bit misunderstood, at least from the perspective of the Aztecs.

Symbols of Huitzilopochtli

Given how much of a hotshot he is, Huitzilopochtli was often connected with various symbols that highlighted his power and significance within Aztec society. Some of the key symbols associated with him include:

- The sun: As the sun god, Huitzilopochtli was responsible for ensuring the sun’s daily journey across the sky.

- The hummingbird: As we mentioned earlier, the hummingbird symbolizes ferocity and determination in battle.

- The Xiuhcoatl was a mythical, serpent-like creature with a fiery tail representing Huitzilopochtli’s divine weapon. Imagine wielding a fire serpent as your primary armament.

- The teocuitlatl: A divine golden ornament representing life’s preciousness and the sun’s divine origin.

Huitzilopochtli Appearance

For a furious deity, Huitzilipochtli sure did have a fresh wardrobe.

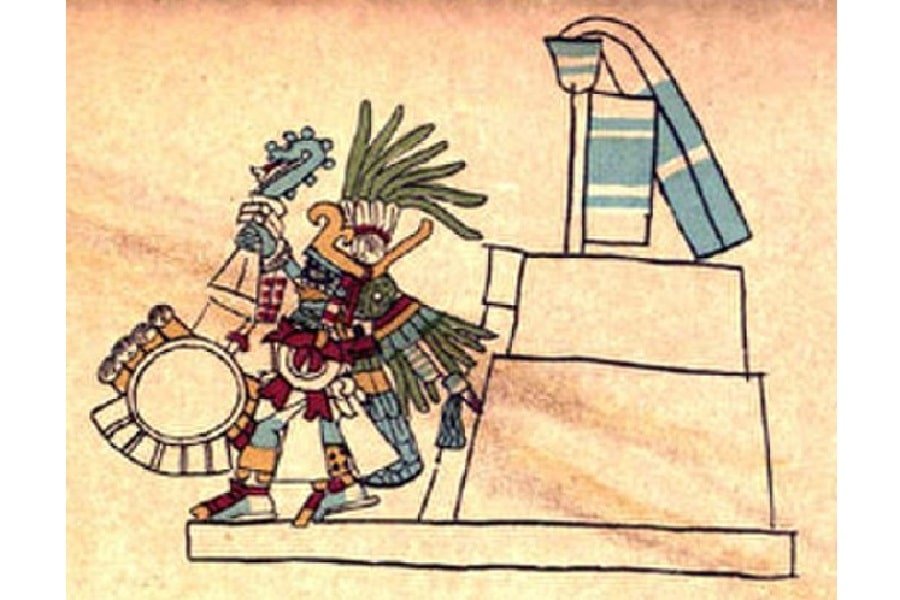

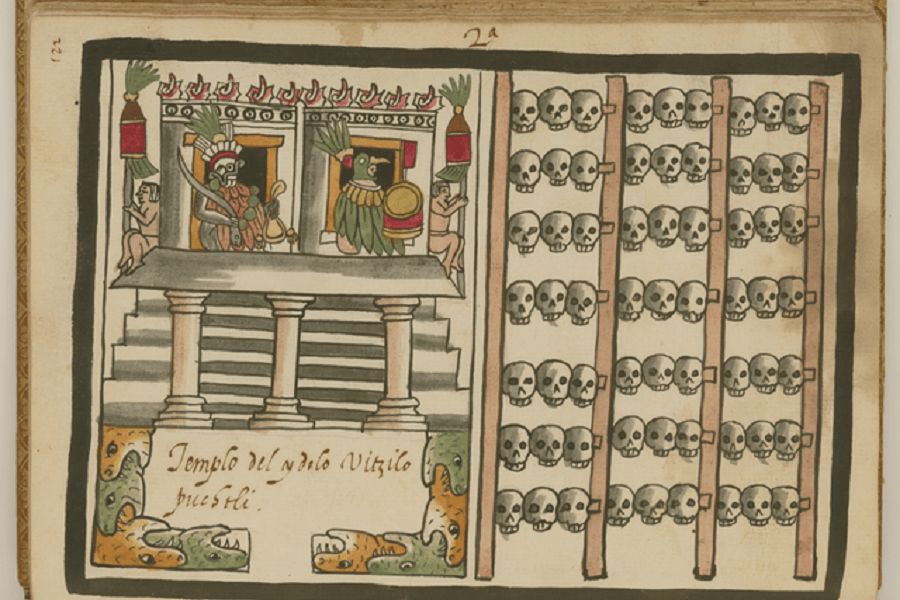

In various iconography (such as the Codex Tovar and the Codex Telleriano-Remensis), Huitzilipochtli is depicted in his human form carrying a red shield and his iconic weapon, Xiuhcoatl, a fire-spitting serpent.

The Codex Borbonicus has a more fantastical representation of him, where Huitzilopochtli stands on top of the serpent hill dressed in colorful battle garb.

The Florentine Codex depicted him as colored in blue stripes and adorned with jewels. On top of this, hummingbird feathers and helmets were common props for Huitzilopochtli’s appearance.

The Origin Myth of Huizilopochtli

The Impregnation of Coatlicue

The origin story of Huitzilopochtli is as wild and fantastical as they come. One day, the goddess Coatlicue, Huitzilopochtli’s mother, was sweeping a temple when a ball of feathers fell from the sky.

Intrigued, she picked it up and placed it in her waistband. To her surprise, this simple act resulted in her becoming pregnant with Huitzilopochtli.

Rogue Children

Coatlicue’s other children, including the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui and the Centzon Huitznahua (Four Hundred Southerners), weren’t too pleased about their mother’s sudden pregnancy.

Given how they figured their brother would be conceived through unnatural means, they decided to take matters into their own hands and put an end to this unborn threat.

So together, the 400 southerners, led by Coyolxauqui, joined hands in raiding their mother to kill Huitzilopochtli.

The Explosive Birth of Huitzilopochtli

Just as Coyolxauhqui and her siblings were about to attack their pregnant mother, Huitzilopochtli sprang to life and made his grand entrance into the world.

Fully armed and ready for battle, Huitzilopochtli emerged, burst forth from his mother’s womb, donning his hummingbird helmet and Xiuhcoatl, and immediately began defending his mother from his treacherous siblings.

Huitzilopochtli’s birth proved to be an endgame for Coyolxauhqui.

With flaming eyes and bulging muscles, the blue hummingbird challenged his sister to a fight for the ages.

Huitzilopochtli and Coyolxauhqui

Coyolxauhqui was no match for her newly-born brother.

In a fierce battle, Huitzilopochtli swiftly defeated her, cutting off her head and limbs before hurling her body down the side of the snake hill.

READ MORE: Snake Gods and Goddesses: 19 Serpent Deities from Around the World

Talk about sibling rivalries not ending too well.

This grisly event was later reenacted in Aztec rituals to honor Huitzilopochtli and ensure his continued protection.

To the Stars and Never Back

As for the Centzon Huitznahua, Huitzilopochtli chased them into the sky, where they became the stars of the southern sky. This battle is portrayed in the Florentine Codex.

From that day on, the hummingbird dedicated himself to defending the sun and the Aztec people from these celestial enemies.

This would forever engage him in a constant battle involving him chasing these four hundred stars perpetually. In the eyes of the Aztecs, this was the explanation for the stars moving in the night sky, with their gradual disappearance as soon as the sun rose in the sky.

Other Origin Stories of Huitzilopochtli

While the tale of Coatlicue’s impregnation and Huitzilopochtli’s explosive birth is the most well-known version of his origin story, other versions have been passed down through the generations.

In some accounts, Huitzilopochtli is said to have been born from the union of the gods Ometeotl and the goddess Omecihuatl. In other stories, he’s portrayed as a divine hero, flaming in the sky, who leads his people to victory against various foes.

Huitzilopochtli Myths

If you thought that was the end of Huitzilopochtli’s adventures, buckle up because there’s more to where that came from.

Throughout Aztec mythology, the hummingbird’s antics are the stuff of legend. Whether he’s guiding his people on a great migration, duking it out with his sorceress sister Malinalxochitl, or founding the great city of Tenochtitlan, Huitzilopochtli is always at the center of the action.

He’s like the Aztec version of James Bond if James Bond wore feathers and demanded human sacrifices.

The Great Migration

Alright, it’s time to dive deep into the roots of Mexico City and see how it relates to our loving Aztec god of war through myths about him.

Once upon a time, in a land called Aztlán, the Aztecs lived under the rule of the ritzy “Azteca Chicomoztoca.” But Huitzilopochtli, the ever-so-wise patron god, had a grand vision for his people.

He told the Aztecs, “Folks, it’s time to embrace your inner wanderlust! Let’s hit the road and find ourselves a shiny new home!” He ordered them to leave Aztlán in search of a new home and change their name to “Mexica” just to shake things up.

So, with Huitzilopochtli as their divine tour guide, the Mexica embarked on an epic journey, leaving behind the comforts of their old home and stepping into the unknown.

Huitzilopochtli and Malinalxochitl

Now, Huitzilopochtli needed a little “me time” to recharge his divine batteries, so he handed the leadership baton to his sister, Malinalxochitl.

She founded a place called Malinalco, but the Mexica quickly realized they preferred Huitzilopochtli’s leadership. They gave him a ring and said, “Hey, big bro, we miss you! Can you come back and show us the way?”

Huitzilopochtli, always up for a good adventure, took charge again. He put his sister to sleep and told the Mexica to swiftly exit before she awoke. When Malinalxochitl finally woke up, she was fuming because of her brother’s sudden change of plans.

She decided to channel her anger into raising a son named Copil, who would grow up with vengeance in his heart. Copil eventually faced off against Huitzilopochtli, but alas, Huitzilopochtli had to strike him down. In a dramatic finale, he hurled Copil’s heart into Lake Texcoco.

The Founding of Tenochtitlan

Years later, Huitzilopochtli thought it was high time for the Mexica to put down roots.

He sent them on a divine scavenger hunt to find Copil’s heart and build their city upon it. The sign they were to look for was an eagle perched on a cactus, casually snacking on a serpent like it was the hottest new appetizer in town.

After years of wandering and more than a few wrong turns, the Mexica finally found their treasure: an island in the middle of Lago Texcoco. This was the destined location for their new home and the birthplace of the illustrious city of Tenochtitlan.

And so, with a dash of humor, a heaping spoonful of drama, and a generous helping of divine intervention, the Mexica founded Tenochtitlan, an abode that would become the beating heart of the Aztec civilization and the roots of the future Mexico City.

The Fall of Huitzilopochtli

Fire in the Basement

During the reign of Moctezuma II, the temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli caught fire, and it wasn’t because of an overzealous ceremony.

The flames raged through the sacred structure, causing considerable damage and leaving a mark on the Aztec people.

And, as with anything in mythology, there’s always a story behind the story.

The Serpent Shadow

When the fire broke out, some believed it was the result of a divine serpent’s shadow passing through the temple.

Was this a sign from Huitzilopochtli himself, or simply a terrible accident? The truth may be lost to the ages, but one thing is for sure: the Aztecs didn’t take this lightly. They saw it as an ominous event, a warning that perhaps their sun god was displeased with them.

Moctezuma II’s Reaction

Moctezuma II was no ordinary ruler. He was the kind of emperor who knew how to keep the balance between divine wrath and the people’s morale. So, when the fire happened, Moctezuma II took it upon himself to appease Huitzilopochtli.

This meant more sacrifices, more ceremonies, and a whole lot of damage control. After all, no one wants to be on the wrong side of an angry sun god.

But even through all of this, people had that unsettling feeling under their skin about imminent doom.

The Spanish Invasion and Huitzilopochtli

You know that awkward moment when uninvited guests show up at your party and completely ruin the vibe?

Well, that’s kind of what happened when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Aztec empire. Hernán Cortés led the Spanish invasion, which threw the Aztec world into chaos.

However, Moctezuma II, initially thought Cortés was a friend when he initially heard reports about the Spanish landing on his shores.

But it wasn’t long before Moctezuma, and the Aztecs realized that Cortés was no divine savior, and the war for their homeland was on. The Spanish forces might’ve deemed the Aztec sacrifices and rituals for their gods to be particularly manic.

As one thing led to another, total war was on the horizon.

The Fall of the Aztec Empire

As much as we’d like to imagine Huitzilopochtli swooping in hummingbird style to save the day, the fall of the Aztec empire was a tragic and brutal affair.

Between the superior weaponry of the Spanish forces, the devastating impact of European diseases, and the alliances Cortés formed with disgruntled indigenous groups, the odds were stacked against the Aztecs.

Despite their fierce resistance and unwavering faith in their sun god, the Aztec empire eventually crumbled under the weight of the Spanish conquest. But even in the face of defeat, the spirit of Huitzilopochtli and the Aztec culture would live on, their resilience and strength echoing through the ages.

Worship of Huitzilopochtli

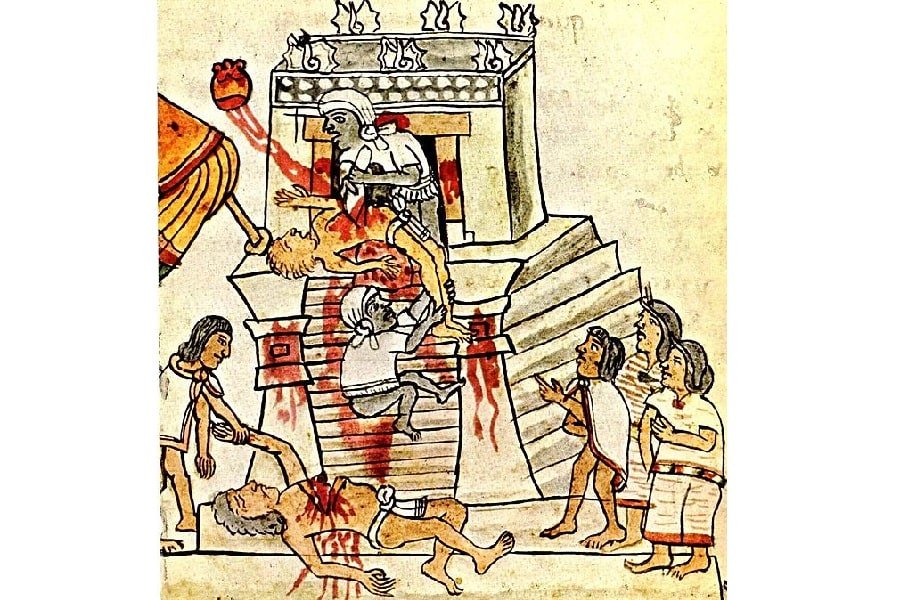

Human Sacrifices

Imagine being an Aztec priest tasked with keeping Huitzilopochtli content. If he’s displeased, the sun won’t rise, and eternal night awaits!

The solution? Human sacrifices! It sounds grim, but there was a lighter side to it.

The “lucky” chosen ones were either war captives or volunteers. Yes, volunteers! They were treated like royalty before their big day, enjoying luxury before the grand finale.

Aztec sacrifices were a spectacle, with elaborate processions, vibrant costumes, and theatrical rituals. Think Oscars, but with a literal red carpet.

Sacrifice methods varied, but for Huitzilopochtli, a priest would skillfully remove the still-beating heart from the offering. A sun god loves a fresh, warm heart!

While shocking to modern folks, the Aztec tradition of human sacrifice was deeply spiritual. So, next time you see a sunrise, remember their audacious way of ensuring the sun kept rising.

READ MORE: Aztec Religion

Huitzilopochtli in Aztec Warfare

As the Aztec war god, Huitzilopochtli played a pivotal role in the empire’s military affairs. He wasn’t just some distant divine figure; he was their go-to deity for protection, guidance, and a sprinkling of divine mojo to ensure victory on the battlefield.

Aztec warriors knew that Huitzilopochtli had their backs and made sure to give him the credit he deserved.

Before heading off to combat, Aztec soldiers would’ve probably gathered for a little pre-game pep talk with Huitzilopochtli. Through rituals and prayers, they would’ve asked for his blessing and guidance to help them defeat their enemies with style and finesse.

Adorning their shields with hummingbird feathers and invoking his name would’ve also been popular. After all, when you’ve got a war god on your side, why settle for anything less than a spectacular victory?

The Aztec Priesthood and Huitzilopochtli

The priesthood of Huitzilopochtli had all the potential to be an elite group within Aztec society.

These priests were entrusted with the sacred duty of maintaining god’s favor and ensuring the continued prosperity of the empire. The priests performed rituals, led ceremonies, and offered sacrifices to satisfy Huitzilopochtli.

The highest-ranking priest, known as the Tlatoani, would even don the god’s ceremonial attire and act as a conduit between the divine and the mortal realms, further cementing Huitzilopochtli’s connection to the Aztec people.

The Templo Mayor

The Templo Mayor, or “The Great Temple,” located in the heart of Tenochtitlan, was the most important temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. This architectural marvel stood as a testament to the god’s power and the Aztec’s devotion.

The temple was the focal point of religious life with its twin pyramids, one dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and the other to the rain god Tlaloc.

READ MORE: Pyramids in America: North, Central, and South American Monuments

Counterparts of Huitzilopochtli: Sun Gods from Around the World:

Huitzilopochtli may have been the Aztec god of war and the rising sun, but he’s far from the only sun deity in the mythological arena. Let’s take a lighthearted look at some of his sun god counterparts from different cultures:

- Ra (Egyptian Mythology): If Huitzilopochtli were to throw a sun god party, Ra would definitely be on the VIP guest list. This ancient Egyptian sun god has style, with his falcon head and sun disk headdress. Plus, he travels across the sky in a solar boat, giving a whole new meaning to “cruising in style.”

- Helios (Greek Mythology): Hailing from sunny Greece, Helios is the personification of the sun. He drives a golden chariot pulled by fiery horses across the sky daily. While he might not have the warrior aspect of Huitzilopochtli, Helios has a flair for the dramatic, making him a worthy counterpart.

- Surya (Hindu Mythology): Surya, the Hindu sun god, boasts a resume that includes giving light, warmth, and life to the world. He’s often depicted riding a chariot with seven horses, representing the colors of the rainbow. With his sun salutation yoga pose and penchant for curing diseases, Surya’s got the whole “mind-body-spirit” thing down.

- Inti (Inca Mythology): Hailing from the Andean highlands, Inti is the Inca god of the sun. As the patron deity of the Inca Empire, Inti was a big deal. He’s often shown as a golden disk with a human face, representing the sun’s life-giving force. Inti and Huitzilopochtli would surely have some interesting conversations about their respective empires.

- Amaterasu (Japanese Mythology): Amaterasu is the Shinto goddess of the sun and the divine ancestor of the Japanese imperial family. Known for her beauty and compassion, she brings a touch of elegance to the sun god scene. Despite her gentle demeanor, she’s no pushover, as proven by her ability to hide the sun when upset, plunging the world into darkness.

Legacy of Huitzilopochtli

While the Aztec Empire may have fallen long ago, the influence of Huitzilopochtli and other deities from the Aztec pantheon can still be observed in modern Mexican culture.

Huitzilopochtli’s story and symbolism have been incorporated into various artistic mediums, such as literature, visual arts, and music, as a reminder of Mexico’s rich cultural heritage.

In fact, the modern Mexican flag pays homage to this legend with its central emblem: an eagle perched on a nopal cactus, holding a snake in its beak and talon. The flag consists of three vertical stripes—green, white, and red—with the coat of arms placed in the center of the white stripe.

The green stripe represents hope, the white represents unity, and the red symbolizes the blood of national heroes. The emblem of the eagle, cactus, and snake is a visual reminder of the Aztec foundation myth and the role of Huitzilopochtli in guiding the Mexica to their promised land.

Conclusion

As the sun sets on Huitzilopochtli, let us reflect, for a moment, on the indelible mark he left on the Aztec people and their culture.

Like the sun’s rays that stretch across the sky, the flutters of the hummingbird’s feathers reached every corner of the empire, illuminating their lives with a sense of purpose, power, and devotion.

And for us, as we look back at a civilization long destroyed by the human thirst for war, we can only sit and marvel at the dreamy stories of a forgotten god of war.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: 16 Oldest Known Cultures From Around The World

References

Carrasco, D. (1999). City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-7719-8.

Smith, M. E. (2003). The Aztecs. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23016-8.

Aguilar-Moreno, M. (2006). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533083-0.

Boone, E. H. (1989). Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 79(2), i-107.

Brundage, B. C. (1979). Huitzilopochtli: World Age and Warfare in the Mexica Cosmos. History of Religions, 18(4), 295-318.

Archaeology held by the University of Cambridge Centre of Latin American Studies, August 1972. University of Texas Press, 1974.