The history of cameras is not defined by slow-moving evolution. Rather, it was a series of world-changing discoveries and inventions followed by the rest of the world catching up. The first camera to take a permanent photograph was invented a hundred years before the portable camera was available to the middle class. A hundred years after that, the camera has become a part of daily life.

Today’s camera is a small, digital addition to the incredible computer that is our smartphone. For the professional, it may be the digital SLR, capable of taking high-definition video or thousands of high-resolution photos. For the nostalgic, it might be a take on the instant cameras of yesteryear. Each of these represent a single leap forward in camera technology.

Table of Contents

When was the camera invented?

The first camera was invented in 1816 by French inventor Nicephore Niepce. His simple camera used paper coated with silver chloride, which would produce a negative of the image (dark where it should be light). Because of how silver chloride works, these images were not permanent. However, later experiments using “Bitumen of Judea” produced permanent photos, some of which remain today.

Who invented the first camera?

French inventor Nicephore Niepce may have created the first photograph in 1816, but his experiments with camera obscura, an ancient technique for capturing an image using a small hole in the wall of a dark room or box, had been occurring for years. Niepce had left his post as Administrator of Nice in 1795 in order to return to his family’s estate and begin scientific research with his brother, Claude.

Nicephore was particularly fascinated with the concept of light and was a fan of early lithographs using the “Camera Obscura” technique. Having read the works of Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Johann Heinrich Schulze, he knew that silver salts would darken when exposed to light and would even change properties. However, like these men before him, he never found a way to make these changes permanent.

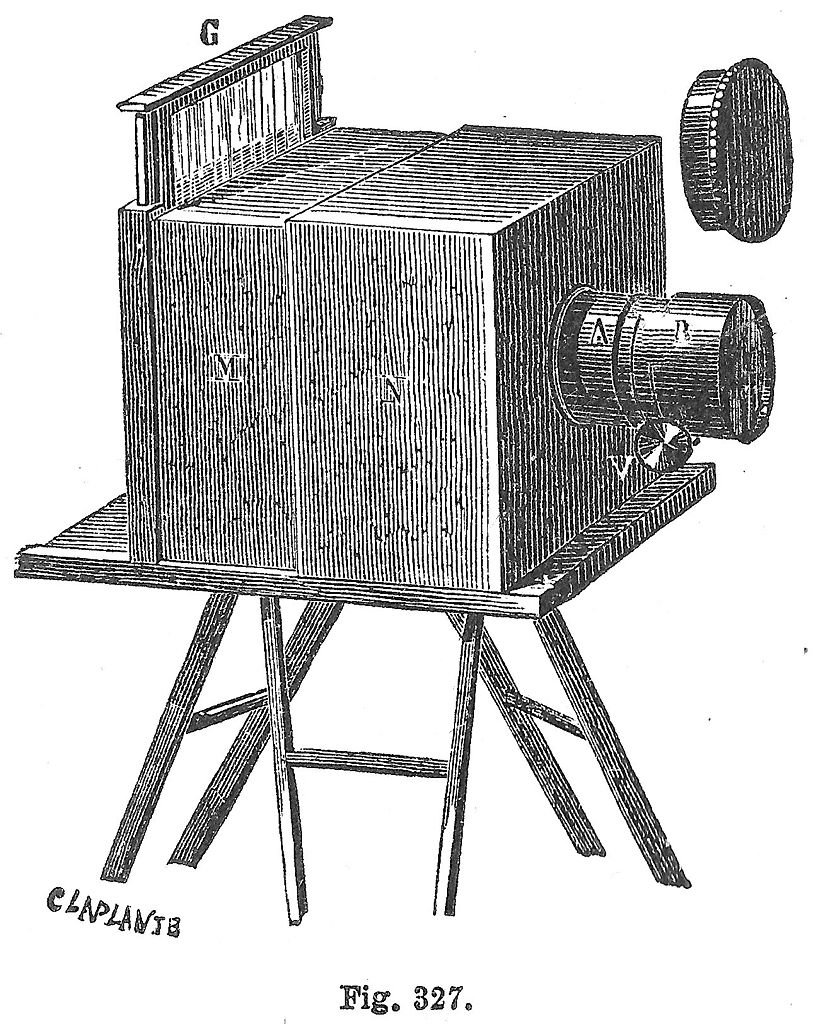

Nicephore Niepce experimented with a range of other substances before turning towards a “film” made from “Bitumen of Judea.” This “bitumen,” sometimes also known as “Asphalt of Syria,” is a semi-solid form of oil that appears like tar. Mixed with pewter, it was found to be the perfect material for Niepce to employ. Using the wooden camera obscura box he had, he could create a permanent image on this surface, though it was quite blurred. Niepce referred to this process as “heliography”.

Excited about further experiments, Niepce began corresponding with his good friend and colleague Louis Daguerre more often. He continued to experiment with other compounds and was confident that somehow the answer lied in silver.

Unfortunately, Nicephore Niepce passed away in 1833. However, his legacy remained as Daguerre continued the work that the french genius had started, eventually producing the first mass-produced device.

What is Camera Obscura?

Camera Obscura is a technique used to create an image by using a small hole in a wall or piece of material. The light entering this hole can project an image of the world outside it onto the opposite wall.

If a person sits in a dark room, camera obscura could allow a hole the size of a pin to project an image of the garden outside on their wall. If you made a box with a hole on one side and thin paper on the other, it could capture the image of the world on that paper.

The camera obscura concept has been known for millennia, with even Aristotle having used a pinhole camera to observe solar eclipses. During the 18th century, the technique led to the creation of portable “camera boxes” that the bored and wealthy would use to practice drawing and painting with. Some art historians argued that even beloved masters like Vermeer took advantage of “cameras” when creating some of their works.

It was such a “camera” that Niepce experimented with when using silver chloride, and the devices would become the basis for his partner’s next great invention.

Daguerreotypes and Calotypes

Louis Daguerre, the scientific partner of Niepce, continued working after the latter genius’ passing. Daguerre was an apprentice of architecture and theater design and obsessed with finding a way to create a simple device to create permanent images. Continuing to experiment with silver, he eventually came across a relatively simple method that worked.

What is a Daguerreotype?

A Daguerreotype is an early form of photo camera, designed by Louis Daguerre in 1839. A plate with a thin film of silver iodide was exposed to light for minutes or hours. Then, in darkness, the photographer would treat it with mercury vapor and heated saltwater. This would remove any silver iodide that the light had not changed, leaving behind a fixed camera image.

Though technically a mirror image of the world it captured, Daguerreotypes produced positive images, unlike the “negatives” of Niepce. While the first daguerreotypes required long exposure times, technological advances decreased this period within a few years so that the camera could even be used to create family portraits.

The daguerreotype was extremely popular, and the French government purchased the rights to the design in exchange for a life pension for Louis and his son. France then presented the technology, and the science behind it, as a gift “free to the world”. This only increased the interest in the technology, and soon every wealthy household would take advantage of this new device.

What is a Calotype?

A Calotype is an early form of photo camera developed by Henry Fox Talbot in the 1830s and presented to the Royal Institute in 1839. Talbot’s design used writing paper soaked in table salt and then brushed lightly with silver nitrate (which was called a “film”). Capturing images due to chemical reactions, the paper could then be “waxed” to save the image.

Calotype images were negatives, like Niecpe’s original photographs, and produced more blurred pictures than the daguerreotype. However, Talbot’s invention required less exposure time.

Patent disputes and blurrier images meant that the Calotype was never as successful as its French counterpart. However, Talbot remained an important figure in the history of cameras. He continued experimenting with chemical processes and eventually developed the early techniques required to create multiple prints from a single negative (as well as progressing our understanding of the physics of light itself).

What was the first camera?

The first mass marketed camera was a daguerreotype camera produced by Alphonse Giroux in 1839. It cost 400 francs (approximately $7,000 by today’s standards). This consumer camera had an exposure time of 5 to 30 minutes, and you could purchase standardized plates in a range of sizes.

The daguerreotype would be replaced in 1850 by a new “colloid process”, which required treating the plates before using them. This process produced sharper images and would require a shorter exposure time. So fast was the exposure time required that they needed the invention of a “shutter” that could quickly expose the plate to light before blocking it again.

However, the next significant advancement in camera technology came in the creation of “film.”

What was the first Roll Film Camera?

American entrepreneur George Eastman created the first camera that used a single roll of paper (and then celluloid) film, called “The Kodak” in 1888.

The Kodak camera could capture negative pictures much like the Calotype. These pictures, however, were sharp like daguerreotypes, and you could measure exposure time in fractions of a second. The film would need to remain in the dark box camera, which would be sent in its entirety back to Eastman’s company for the images to be processed. The first Kodak camera had a roll that could hold 100 pictures.

The Kodak Camera

The Kodak cost only $25 and came with the catchy slogan, “You press the button… we do the rest.” The Eastman Kodak Company became one of the largest companies in America, with Eastman himself becoming one of the richest men. In 1900, the company created the most simplistic, high-quality camera available to the middle class – The Kodak Brownie. This American box camera was relatively inexpensive. Being so accessible to the middle class helped popularize the use of photography as a way to commemorate birthdays, vacations, and family gatherings. As development costs decreased, people could take photos for any reason, or no reason at all.

By the time of his death, his philanthropy was only rivaled by Rockefeller and Carnegie. His donations included $22 Million to MIT to continue investigating new technology. His company, Kodak, continued to dominate the camera market until the rise of digital camera technology in the 1990s.

Thanks to the popularity of Kodak products and the introduction of other portable cameras, film cameras made using image plate processes obsolete.

What is a 35 mm Film?

35mm, or 135 Film was introduced by the Kodak camera company in 1934 and quickly became the standard. This film was 35mm wide, with each “frame” having a height of 24mm for a 1:1.5 ratio. This allowed for the same “cassette” or “roll” of film to be used in the cameras of a different brand and quickly became the norm.

35mm film would come in a cassette shielding it from light. The photographer would place it into the camera and would “wind” it onto a spool within the device. The film was wound back into the cassette as each photograph was taken. When they opened the camera once more, the film would be back safely in the cassette, ready for processing.

A standard cassette of 135 film would have 36 exposures (or photos) available, while later films contained 20 or 12.

The 35mm film was popularized with the production of the famous Leica camera, but other cameras soon followed suit. 35mm is now the most commonly used film in analog photography. Disposable cameras use 135 film encased within the cheap camera rather than within a cassette that could be replaced. While it may be challenging to find a nearby processor, many photographers still use 135 film.

The Leica

The Leica (a portmanteau of “Leitz Camera”) was first designed in 1913. Its thin and lightweight design quickly gained popularity, and the addition of collapsible and detachable lenses turned it into the handheld camera all other manufacturers attempted to copy.

When Ernst Leitz took over the directorship of the Optical Institute in 1869, the German engineer was only 27. The institute made its money selling lenses, primarily in the form of microscopes and telescopes.

However, Leitz had been trained in watchmaking and other small engineering projects. He was a leader who believed success came from designing the next technology and encouraged his employees to experiment more often. In 1879, the company changed names to reflect its new director. The company moved to binoculars and more complex microscopes soon after.

In 1911, Leitz hired a young Oskar Barnack, who was obsessed with creating the perfect portable camera. Encouraged by his mentor, he was given significant funding and resources to do so. The result, which arrived in 1930, was The Leica One. It had a screw-thread attachment to change lenses, of which the company offered three. It sold three thousand units.

The Leica II arrived only a couple of years later, with the company adding a range finder and separate viewfinder. The Leica III, produced in 1932, included a shutter speed of 1/1000th of a second and was so popular they were still being made in the mid-fifties.

The Leica set a new standard, and the influence of its design can be seen in the cameras of today. While Kodak’s cameras may have been the most popular of the day, Leica’s changed the industry permanently. Kodak themselves replied with the Retina I, while a fledgling camera company in Japan, Canon, produced its first 35mm in 1936.

What was The First Movie Camera?

The first movie camera was invented in 1882 by Étienne-Jules Marey, a French inventor. Called the “chronophotographic gun,” it took 12 images a second and exposed them on a single curved plate.

At the most superficial level, a movie camera is a regular photographic camera that can take repeated images at a high rate. When used in movies, these images are referred to as “frames.” The most famous early movie camera was the “Kinetograph,” a device created by engineer William Dickson in Thomas Edison’s laboratories, the same place where the first lightbulb was invented. It was powered by an electric motor, used celluloid film, and ran at 20 to 40 frames per second.

This 1891 invention signaled the beginning of cinematography, and early sheets of film from the camera are still in existence. Modern movie cameras are digital and can record tens of thousands of frames a second.

The First Single-lens Reflex Cameras (SLRs)

Thomas Sutton developed the first camera to use single-lens reflex (SLR) technology in 1861. It employed the technology used before in camera obscura devices – reflex mirrors would allow a user to look through the camera’s lens and see the exact image recorded on film.

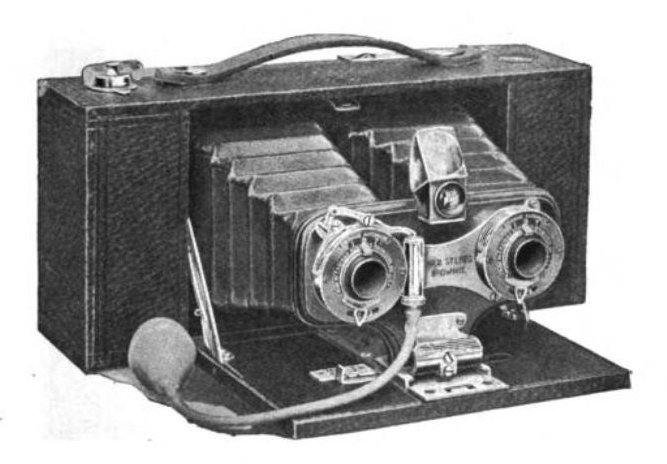

Other cameras at the time used “Twin-lens reflex cameras,” in which the user would see through a separate lens and see a slightly different image than what was recorded on the plate or film.

While single-lens reflex cameras were the superior choice, the technology behind them was complex for nineteenth-century camera manufacturers. When companies such as Kodak and Leica produced their own economically viable mass marketed cameras, they also avoided single-lens reflex cameras because of the costs. Even today, disposable cameras rely on the twin-lens camera instead.

However, the single-lens reflex camera was essential for those with money who were serious about developing their passion for technology. The first 35mm SLR was the “Filmanka,” which came out of the Soviet Union in 1931. However, this had only a short production run and used a waist-level viewfinder.

The first mass-marketed SLR that properly utilized the design we know today was the Italian “Rectaflex,” which had a run of 1000 cameras before production was halted due to World War II.,

The SLR camera soon became the camera of choice for hobbyists and professional photographers. New technology allowed the reflexive mirror to “flip up” when the shutter opened, meaning the image through the viewfinder was perfectly like that captured on film. As Japanese camera companies started to produce high-quality devices, they focussed entirely on SLR systems. Pentax, Minolta, Canon, and Nikon are now considered the most competitive camera companies globally, almost wholly due to their perfection of the SLR. Newer models included light meters and range-finders within the viewfinder, as well as easily-adjustable settings for shutter speed and aperture sizes.

What was The First Auto-focus Camera?

Before 1978, a camera lens would need to be manipulated so that the clearest picture would reach the plate or film. The photographer would do this by making slight movements to change the distance between the lens and the film, usually by turning the lens mechanism.

The first cameras had a fixed focus lens that could not be manipulated, which meant that the camera needed to be at an exact distance from the subjects, and all subjects had to be at that same distance. Within years of the first daguerreotype camera, inventors realized they could create a lens that could be moved to suit the distance between device and subject. They would use primitive rangefinders to determine how the lens needed to be changed for the clearest photo.

During the eighties, camera manufacturers were able to use additional mirrors and electronic sensors to determine the ultimate placement of the lens and small motors to manipulate them automatically. This auto-focus capability was first seen in the Polaroid SX-70, but by the mid-eighties was standard in most high-end SLRs. Auto-focus was an optional feature so that professional photographers could choose their own setting if they wanted the image to be clearer away from the center of the photograph.

The First Color Photography

The first color photograph was created in 1961 by Thomas Sutton (the inventor of the single-lens reflex camera). He made the photograph by using three separate monochrome plates. Sutton created this photo specifically to use in the lectures of James Maxwell, the man who discovered that we could make any visible color as a combination of Red, Green, and Blue.

The first photographic camera presented its images in monochrome, showing black and white images in final form. Sometimes, the single color might be blue, silver, or gray – but it would only be one color.

From the beginning, inventors wanted to find a way to produce images in the colors we see as humans . While some found success in using multiple plays, others tried to find a new chemical with which they could coat the photographic plate. A relatively successful method used color filters between the lens and plate.

Eventually, through much experimentation, inventors were able to develop a film that could capture colorBy 1935, Kodak was able to produce “Kodachrome” film. It contained three different emulsions layered on the same film, each “recording” its own color. The creation of the film, as well as the processing of it, was an expensive task and so was out of reach for the middle-class users that were beginning to take up photography as a hobby.

It was not until the middle of the 1960s that color film became as financially accessible as black-and-white. Today, some analog photographers still prefer black and white, insisting that the film produces a clearer picture. Modern digital cameras use the same three-color system to record color, but the results depend more on recording the data.

The Polaroid Camera

The instant camera can produce the photograph within the device, rather than requiring the film to be developed later. Edwin Land invented it in 1948, and his Polaroid Corporation cornered the market for the next fifty years. Polaroid was so famous that the camera has undergone “genericization”. Photographers today may not even know that Polaroid is a brand, not the instant camera itself.

The instant camera worked by having the film negative taped to the positive with a film of processing material. Initially, the user would peel the two pieces, with the negative discarded. Later versions of the camera would peel away the negative from within and eject only the positive. The most popular photographic film used for instant cameras was approximately three inches square, with a distinctive white border.

Polaroid cameras were quite popular during the seventies and eighties but suffered near obsolescence due to the rise of the digital camera. Recently, Polaroid has seen a resurgence in popularity on a wave of “retro” nostalgia.

What Were The First Digital Cameras?

While digital photography was theorized as early as 1961, it wasn’t until Kodak engineer Steven Sasson put his mind to it that engineers created a working prototype. His 1975 creation weighed four kilograms and captured black and white images onto a cassette tape. This digital camera also required a unique screen to be looked at and could not print the pictures.

Sasson made this first digital camera possible thanks to the “charged-coupled device” (CCD). This device used electrodes that would change voltage when exposed to light. The CCD was developed in 1969 by Willard S. Boyle and George E. Smith, who later earned the Nobel Prize in physics for their invention.

Sasson’s device had a resolution of 0.01 megapixels (100 x 100) and took 23 seconds of exposure to record an image. Today’s smartphones are over ten thousand times clearer and can take pictures in the smallest fractions of a second.

The first commercially available handheld camera which used digital photography was the 1990 Dycam Model 1. Created by Logitech, it used a similar CCD to Sasson’s original design but recorded the data onto the internal memory (which came in the form of 1 megabyte of RAM). The camera could then be connected to your personal computer and the image could be “downloaded” onto it for viewing or printing.

Digital manipulation software arrived on personal computers in 1990, which increased the popularity of digital cameras. Now images could be processed and manipulated at home without the need for costly materials or a dark room.

Digital single-lens Reflex Cameras (DSLRs) became the next big thing, and Japanese camera companies were especially excited. Nikon and Canon soon cornered the market with their high-quality devices that included digital viewfinders that could look at previous pictures. By 2010, Canon controlled 44.5% of the DSLR market, followed by Nikon with 29.8% and Sony with 11.9%.

The Camera Phone

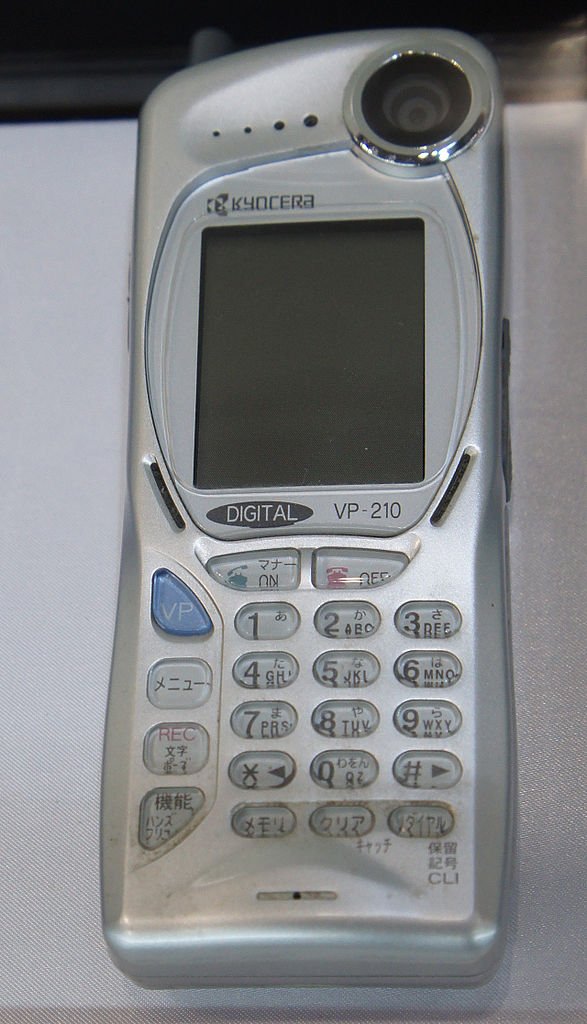

The first camera phone was the Kyocera VP-210. Developed in 1999, it included a 110,000-pixel camera and a 2-inch color screen to view the photos. It was quickly followed up by digital cameras from Sharp and Samsung.

When Apple released their first iPhone, camera phones became a helpful tool rather than a fun gimmick. The iPhone could send and receive images via a cellular network and used new complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) chips. These chips replaced CCDs by being less energy-intensive and offering a more specific data recording.

It would be hard to imagine a mobile phone that did not include a digital camera today. The iPhone 13 has multiple lenses and works as a video camera with 12 megapixels of resolution. That is 12,000 times the resolution of the original device created in 1975.

Modern Photography

While most of us today have digital cameras in our pockets, high-quality SLRs still have a role to play. From professional wedding photographers to cinematographers looking for lightweight film cameras, devices like the Canon 5D are a necessary tool. In a wave of nostalgia, hobbyists are returning to 35mm film, claiming it “has more soul” than its digital counterparts.

The history of the camera is long, with many great leaps forward followed by years of perfecting the technology. From the first camera to the modern smartphone, we have come a long way in searching for the perfect picture.

Sorry next thought “Camera Obscura”?

How was the Camera Obscura originally inspired, though?