Dionysus is one of the most popular ancient Greek gods both today and in ancient times. We associate him with wine, theater, and “the bacchanalia,” aka rich Roman orgies. In academic circles, the role he played in Greek mythology was complex and sometimes contradictory, but his followers played crucial roles in the evolution of Ancient Greece. Many of his mysteries remain a secret forever.

Table of Contents

Who is Dionysius?

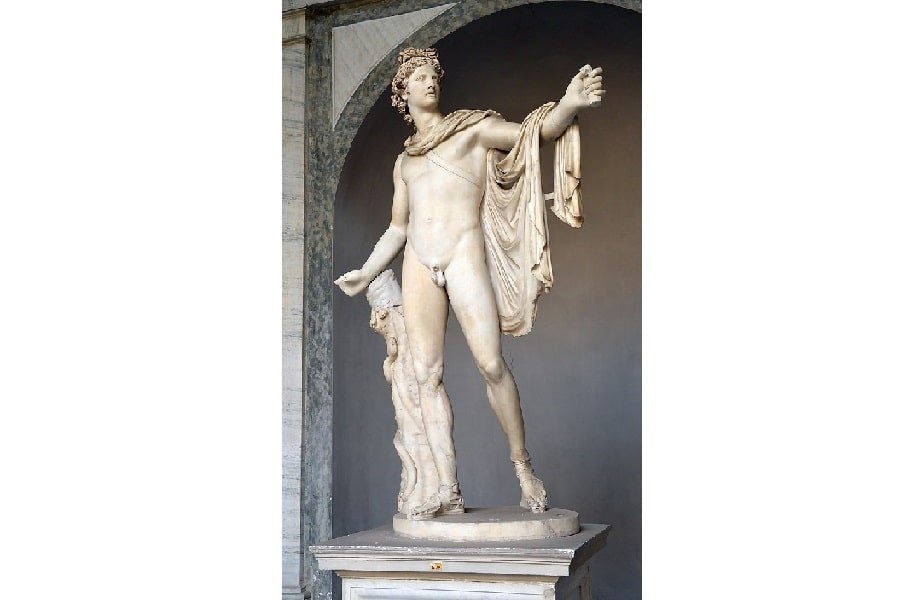

Dionysus is the god of wine, fertility, and revelry in Greek mythology. He is one of the twelve Olympian gods and is often associated with the joyous celebration of life and the grape harvest. Dionysus is the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and the mortal princess Semele.

Dionysus is often depicted as a youthful, long-haired figure, crowned with grapevines and holding a thyrsus (a staff wrapped in ivy or vine leaves).

The worship of Dionysus played a significant role in ancient Greek culture, particularly through festivals such as the Dionysia and the rural Dionysia, which included dramatic performances and revelries. These festivals honored Dionysus and served as an outlet for catharsis and emotional release for the ancient Greeks.

Dionysus’ mythology and worship have inspired numerous works of art, literature, and theater throughout history, making him an enduring and influential figure in both ancient and modern cultures.

The Stories of Dionysus

The mythological story of Dionysus is exciting, beautiful, and full of meaning that is still relevant today. The child Dionysus only reached adulthood thanks to the work of his uncle, while the adult god suffers great loss before discovering wine. He travels the whole of civilization, leads armies, and even visits the underworld on multiple occasions. He mourns without crying and rejoices at the reversal of fate. The story of Dionysus is a compelling one, and it is difficult to do it the justice it deserves.

The (Twice) Birth of Dionysus

The first birth of Dionysus was in Crete, born of Zeus and Persephone. Those of Crete said that he formed the islands later known as the Dionysiadae. Little is known about this first incarnation other than that Orpheus, the infamous Greek seer, said he was torn into pieces by the Titans during their conflict with Zeus. Zeus was about to save his spirit, however, and offered it later as a drink to his lover, Semele.

Semele was a princess of Thebes and a priestess of Zeus. Upon seeing her bathe as he was roaming the world as an eagle, Zeus fell in love with the woman, who he quickly seduced. She insisted he gives her a child and soon fell pregnant. Zeus’ own wife, Hera, heard of the event and went into a rage. She began her plans to kill the woman and her unborn child.

So happy he was with his lover that, one day along the River Styx, Zeus offered Semele a boon – whatever she asked he would give to her. Tricked by a disguised Hera, and unaware of the consequences, Semele made this very request:

“Come unto me in all

the splendor of thy glory, as thy might

is shown to Juno [Hera], goddess of the skies”. (Metamorphoses)

Semele did not understand that no mortal could see the form of a god and live. Zeus, however, knew. He knew and he was scared. He did his best to avoid the inevitable outcome – he produced the smallest lightning and attempted to create the calmest of thunders.

It was not enough. The instant Semele saw the great god, she burned up and died.

The unborn child, however, was still alive. Quickly, Zeus gathered up the fetus and sewed it into his thigh. Zeus carried the fetus in his leg until it was ready to be born, giving him a pronounced limp for the months to follow.

While some followers would call the child “Demeter,” or “twice-born,” he was given the name “Dionysus,” which mythology recorded as meaning “Zeus-limp”. According to the Suda, “Dionysus” means “for those who live the wild life.” In Roman literature, he was known as “Bacchus” and later works would use this name interchangeably. At times, the Romans would also use the name “Liber Pater,” though this analogous god would sometimes take on stories and qualities of other Olympian gods as well.

The Exodus of Child Dionysus

While he was rarely presented as such in art, the baby Dionysus was thin and horned, but soon grew into a handsome child. Hera was unhappy that he had survived and vowed to kill him. So, Zeus’ entrusted the infant god with his brother, Hermes, who spirited him away to be placed under the care of river nymphs. Finding him easily, Hera turned the nymphs to madness, and they attempted to kill the boy. Hermes once more saved him, and this time put him in the hands of Ino.

Ino was Semele’s sister, sometimes called “The Queen of the Sea.” She raised the son of Zeus as a girl, in the hope to hide him from Hera, and her maidservant Mystis taught him the mysteries, those sacred rituals that would be repeated for millennia by his followers. Being of a mortal parent, the infant Dionysus was not considered worthy of the protection afforded to the other 12 Olympian gods, and it was not a title he would claim until an older age.

Hera caught up once more, and Hermes fled with the boy to the mountains of Lydia, a kingdom in what is now central Turkey. Here, he took the form of an ancient god called Phanes, who even Hera would not cross. Giving up, Hera returned home, and Hermes left the young Dionysus in the care of his grandmother Rheia.

Dionysus and Ampelos

The young man, now free from being pursued, spent his adolescence swimming, hunting, and enjoying life. It was during such happy times that the young god met Ampelos, his first love and perhaps the most important character in the story of Dionysus.

Ampelos was a young human (or sometimes a Satyr) from the Phrygian hills. He was one of the most beautiful people in Greek mythology, described in great flowering detail in many of the texts.

“From his rosy lips escaped a voice breathing honey. Spring itself shone from his limbs; where his silvery foot stept the meadow blushed with roses; if he turned his eyes, the gleam of the bright eyeballs as soft as a cow’s eye was like the light of the full moon.” (Nonnus)

Ampelos was explicitly Dionysus’ lover, but also his best friend. They would swim and hunt together and were rarely apart. One day, however, Ampelos wanted to explore a nearby forest and went alone. Despite his visions of dragons taking the young boy away, Dionysus did not follow him.

Unfortunately, Ampelos, now quite well known for his connection to the god, was discovered by Ate. Ate, sometimes called “the death-bringing spirit of Delusion,” was another child of Zeus, and looking for the blessings of Hera. Previously, Ate had helped the goddess ensure her child Eurystheus received the royal blessings of Zeus instead of Heracles.

After discovering the beautiful young boy, Ate pretended to be another youth and encouraged Ampelos to attempt to ride a wild bull. Unsurprisingly, this ruse was to be the death of Ampelos. It is described that the bull bucked him off, after which he broke his neck, was gored, and decapitated.

The Mourning of Dionysus and the Creation of Wine

Dionysus was distraught. While unable to physically cry, he railed against his father and screamed at his divine nature — unable to die, he would never join Ampelos in Hades‘ realm. The young god stopped hunting, dancing, or reveling with his friends. Things began to look very grim.

The mourning of Dionysus was felt the world over. The oceans stormed, and fig trees moaned. The Olive trees shed their leaves. Even the gods cried.

Fate intervened. Or, more accurately, one of the Fates. Atropos heard the lamentations of Zeus’ son and told the young man that his mourning would “undo the inflexible threads of unturning Fate, [and] turned back the irrevocable.”

Dionysus witnessed a miracle. His love rose from the grave, not in human form but as a large grapevine. His feet formed roots in the ground, and his fingers became small branches outstretched. From his elbows and neck grew bunches of plump grapes and from horns on his head grew out new plants, as he slowly continued to grow across as an orchard.

The fruit ripened quickly. Untaught by anyone, Dionysus plucked the ready fruit and squeezed it in his hands. His skin became covered in purple juice as it fell into a curved ox-horn.

Tasting the drink, Dionysus experienced a second miracle. This was not the wine of the past, and it could not be compared to the juice of apples, corn, or figs. The drink filled him with joy. Collecting more grapes, he laid them out and danced on them, creating more of the intoxicating wine. Satyrs and various mythical beings joined the drunken god and celebrations lasted weeks.

READ MORE: Who Invented Wine? Unveiling the Ancient Origins

From this point on, the story of Dionysus changes. He began involving himself more in the affairs of humans, traveling through all of ancient civilization and being especially interested in the people of the east (India). He led battles and offered boons, but all the time brought with him the secret of wine, and the festivities held around its offering.

Alternatives to the Creation of Wine Myth

There are other versions of the wine-creation myth associated with Dionysus. In some, he is taught the ways of viniculture by Cybele. In others, he created the vine as a gift for Ampelos, but when he cut the branches they fell and killed the young man. Of the many myths that are found in Greek and Roman writings, all agree that Dionysus was the creator or discoverer of intoxicating wine, with all previous wine being without these powers.

Underworld Dionysus

Dionysus had entered the underworld at least once (although perhaps more, if you believe some scholars, or include his appearance in the theater). In mythology, Dionysus was known to have traveled to the underworld in order to retrieve his mother, Semele, and take her to her rightful place in Olympus.

On his trip to the underworld, Dionysus needed to pass Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the gates. The beast was restrained by his half-brother Heracles, who had previously dealt with the dog as part of his labors. Dionysus was then able to retrieve his mother from a lake that was said to have no bed, and depths unfathomable. For many, this was proof to gods and humans that Dionysus was truly a god, and his mother worthy of status as a goddess.

The retrieval of Semele was commemorated as part of the Dionysian mysteries, with an annual night-time festival held in secret.

Dionysus in Other Famous Mythology

While most of the stories surrounding Dionysus focus entirely on the god, he does crop up in other stories of mythology, some of which are well-known today.

Perhaps the most famous of these is the story of King Midas. While even the children of today are taught about the king who wished to “turn everything he touched into gold,” and the warning to “be careful what you wish for,” few versions remember to include that this wish was a reward, offered up by Dionysus himself. Midas had been rewarded for having taken in a strange old man who had become lost – a man discovered to be Silenus, the teacher and father figure to the god of wine.

In other stories, he appears as a boy captured by pirates who then turned them into dolphins, and was responsible for Theseus’ abandonment of Ariadne.

In what might be the most surprising story, Dionysus even plays a role in saving his evil stepmother, Hera. Hephaestus, the blacksmith of the gods, was a son of Hera cast out for his deformity. To seek revenge, he created a golden throne and sent it to Olympus as “a gift”. As soon as Hera sat on it, she became caught, unable to move. No other gods could remove her from the contraption, and only Hephaestus would be able to undo the machines that kept her there. They implored Dionysus who, in a better mood than usual, went to his step-brother and proceeded to get him drunk. He then brought the inebriated god to Olympus where they freed Hera once more.

Dionysus’ Children

While Dionysus had many children with multiple women, there are only a few that are worth mentioning:

- Priapus — A minor god of fertility, he is represented by a large phallus. His story is one of lust and disturbing rape scenes but he is now best known for giving a name to the medical condition Priapism, which is essentially an uncontrollable erection caused by spinal damage.

- The Graces – or Charites — Handmaidens to Aphrodite, sometimes they are referred to as daughters of Zeus. Worth mentioning as cults sprang up around them alone, devoted to concepts of fertility.

Sources of the Dionysus Mythology Today

Most of the story offered up in this article comes from a single source, perhaps the most important text when it comes to the study of Dionysus. The Dionysiaca, by the Greek poet Nonnus, was an epic spanning over twenty thousand lines. Written in the fifth century AD, this is the longest surviving poem from antiquity. The story could be seen as a compilation of all the most commonly known works about the god at the time. Nonnus is also known for a well-received “paraphrase” of the gospel of John, and his work was considered relatively well-known for the time. Little about the man himself, however, is known.

The next most important work when discussing the mythology that surrounds Dionysus would be that of Diodorus Siculus, a first-century BC historian, whose Bibliotheca Historica included a section dedicated to the life and exploits of Dionysus.

The Bibliotheca Historica was an important encyclopedia for the time, covering history as far back as the myths, all the way to the contemporary events of 60 BC. Diodorus’ work regarding recent history is now considered to be mostly an exaggeration in the name of patriotism, while the remainder of the volumes is considered a compilation of the works of previous historians. Despite this, the work is seen as important for its records of geography, detailed descriptions, and discussions of historiography at the time.

For contemporaries, Diodorus was revered, with Pliny the Elder regarding him as one of the most venerated of ancient writers. While the encyclopedia was considered so important as to be copied for generations, we no longer have a full collection intact. Today, all that remains are volumes 1-5, 11-20, and fragments found quoted in other books.

Besides these two texts, Dionysus makes appearances in many famous works of classical literature, including Gaius Julius Hyginus’s Fabulae, Herodotus’ Histories, Ovid’s Fasti, and Homer’s Iliad.

Minor details of Dionysus’ story are gathered together from ancient artworks, Orphic and Homeric Hymns, as well as later references to oral histories.

Analogous Divinities

Since as early as the fourth century BC, historians have been fascinated with the connections between religions. For this reason, there have been countless attempts to connect Dionysus to other gods, even within the Greek pantheon.

Among the divinities most associated with Dionysus, the most common are the Egyptian god, Osiris, and the Greek God, Hades. There is good reason for these connections, as works and pieces have been found connecting the three gods in one way or another. Sometimes, Dionysus was called “the subterranean,” and some cults believed in a holy trinity, combining Zeus, Hades, and Dionysus. For some ancient Romans, there were not two Dionysus’, but the younger was named Hades.

It would come as no surprise to modern readers that Dionysus has also been compared to the Christian Christ. In The Bacchae, Dionysus must prove his divinity in front of King Pentheus, while some scholars have attempted to argue that “The Lord’s Supper” was, in fact, one of the Dionysian mysteries. Both gods went through death and rebirth, with their birth being of supernatural nature.

There is, however, little to support these arguments. In the play, the King is torn to shreds, while the story of Christ ends with the god’s execution. Hundreds of gods around the world have had similar death-rebirth stories, and there is simply no evidence that the mysteries contained a ritual similar to the Lord’s Supper.

The Dionysian Mysteries and Cult of Dionysus

Despite questions as to when Dionysus was considered one of the Olympians, the god clearly played a major role in the religious life of the ancient Greeks. The Cult of Dionysus can be traced back nearly fifteen hundred years before Christ, with his name appearing on tablets that date back to that time.

Little is known about the precise rituals that occurred as part of the original mysteries, although the drinking of alcoholic wine played a central role. Modern scholars posit that other psychoactive substances may have also been involved, as early depictions of the god included poppy flowers. The role of wine and other substances was to help the followers of the god, Dionysus, to reach a form of religious ecstasy, freeing themselves from the mortal world. Contrary to some popular stories of today, there is no evidence of human sacrifices, while offerings to the Greek god were more likely to include fruit than meat.

Rites were based on the theme of seasonal death and rebirth. Musical instruments and dancing played major roles. The Orphic Hymns, a collection of chants and psalms dedicated to Greek gods, includes a number to Dionysus that were likely used during the mysteries.

Individual cults of Dionysus would sometimes appear, which followed separate mysteries and rituals. There has been evidence that some practiced monotheism (the idea that Dionysus was the only god),

While the original cult of Dionysus was filled with mysteries and esoteric knowledge, the popularity of the god soon led to more public celebrations and festivals. In Athens, this culminated in the “City of Dionysia,” a festival that lasted days or weeks. It was thought to have been established sometime around 530 BC and is today considered the birthplace of Greek drama and European theater as we now know it.

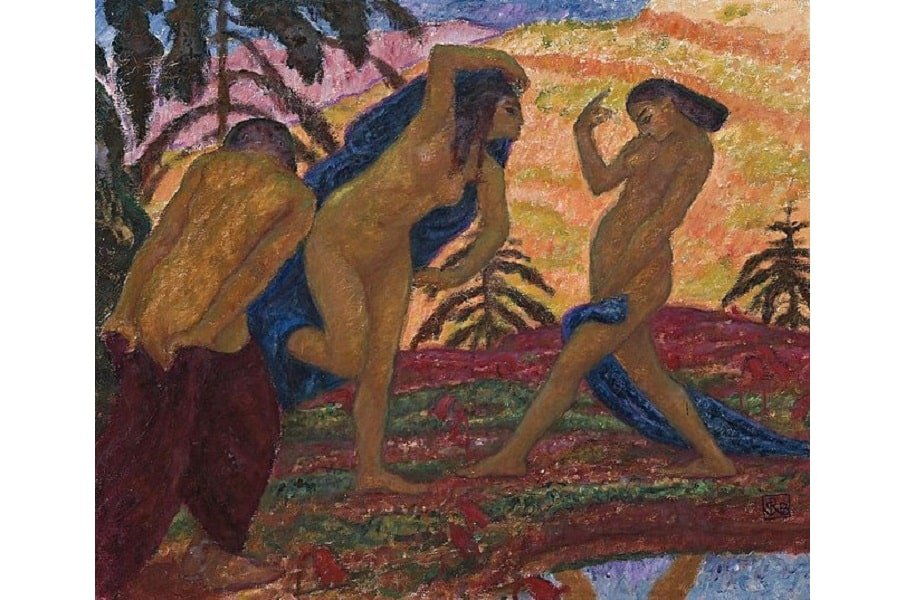

Maenads

Maenads, Bacchae, or “the raving ones” have a strange history. While the word was used in ancient Greece to signify followers of the Dionysian mysteries, the word was also used to refer to the women in the retinue of the Greek god. They are referred to in many contemporary artworks of the time, often dressed scantily, and feeding on the grapes held by the god. Maenads were known as drunken, promiscuous women often considered mad. In The Bacchae, it is the Maenads who kill the king.

By the third century BC, priestesses of Dionysus were given the name “Maedad,” some of whom would even be taught by the Oracle of Delphi.

Dionysian Theater

While Dionysus may be most well-known today for being associated with wine, this mythological story is not the most important contribution of the Dionysian cult. While Greek mythology may be fact or fiction, historical records are more certain about the mysteries’ contribution to the creation of theater as we know it today.

By 550 BC, the secret mysteries of the cult of Dionysus were slowly becoming more public. Festivals open to everyone were held, eventually becoming the five-day event, held annually in Athens, called “The City of Dionysia”.

The event began with a large parade, which included the carrying of emblems that represented the ancient Greek god, including large wooden phalluses, masks, and an effigy of the mutilated Dionysus. People would greedily consume gallons of wine, while sacrifices of fruit, meats, and valuables were offered to the priestesses.

Dionysian Dithyrambs

Later in the week, the leaders of Athens would hold a “dithyramb” competition. “Dithyrambs” are hymns, sung by a chorus of men. In the Dionysian competition, each of the ten tribes of Athens would contribute a chorus made of one hundred men and boys. They would sing an original hymn to Dionysus. It is unknown how this competition was judged, and sadly no “dithyrambs” were recorded that have survived.

Tragedy, Satyr Plays, and Comedies

Over time, this competition changed. The singing of “dithyrambs” was no longer enough. Instead, each tribe would need to present three “tragedies” and a “satyr play.” “Tragedies” would be retellings of stories from Greek mythology, often focusing on the more dramatic moments of the Olympians — betrayal, suffering, and death. The only remaining “tragedy” from the City of Dionysia is Euripedes’ The Bacchae. It also contains a “dithyramb” as its opening chorus, although there is no evidence it was ever used in competition separate from the play.

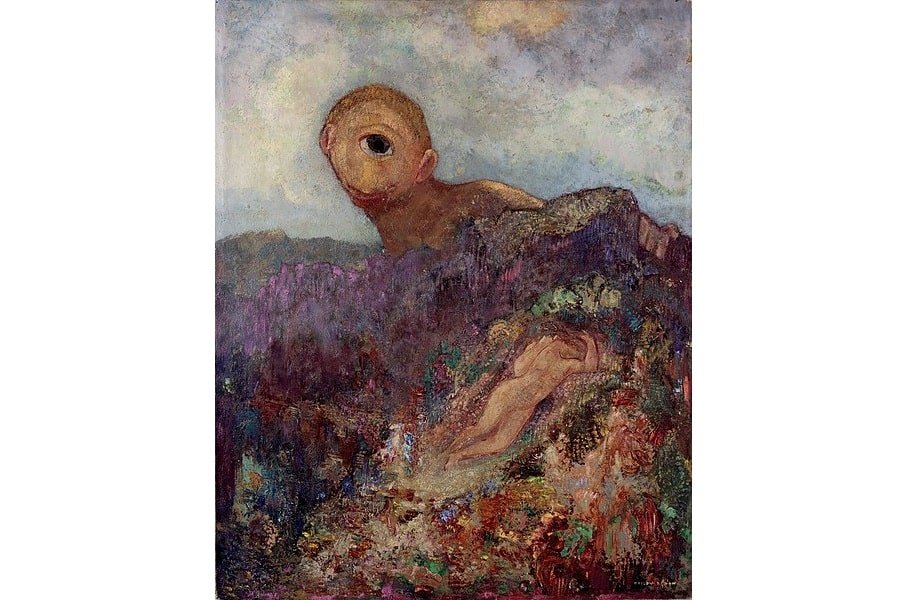

A “satyr play” on the other hand, was a farce, meant to celebrate life and festivities, often quite sexual in nature. The only “satyr play” that remains today is Euripedes’ Cyclops, a burlesque telling of Odysseus’ encounter with the mythological beast.

Out of these two types of plays came a third: the “comedy.” The comedy was different from a “satyr play.” According to Aristotle, this new form was developed out of the revelry of followers and was less farce than an optimistic view of the stories usually covered in tragedies. The Frogs, while “satyrical” (or, if you will, satirical), is a comedy.

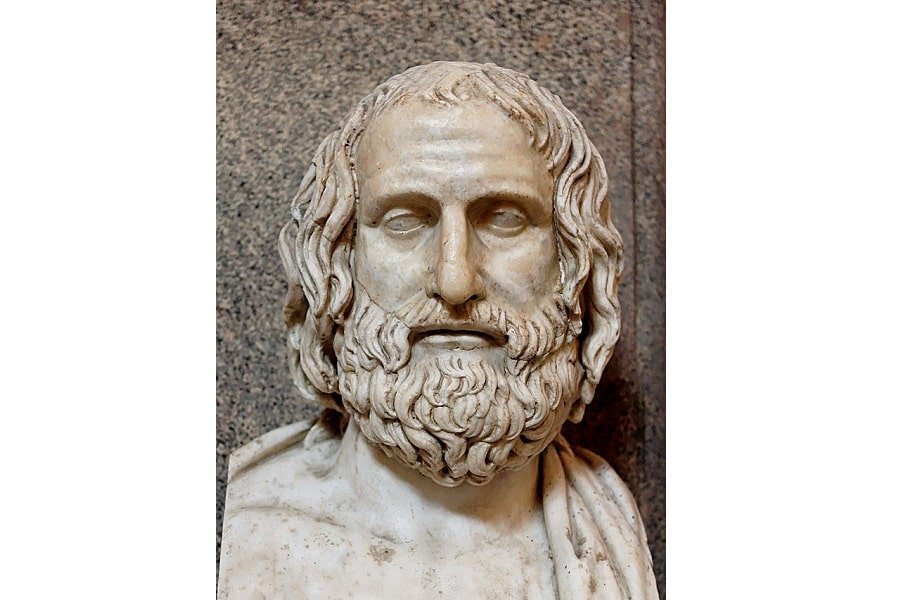

The Bacchae

The Bacchae is a play written by the undisputable greatest playwright in ancient history, Euripedes. Euripedes had previously been responsible for plays such as Medea, The Trojan Women, and Electra. His works have been considered so important to the creation of theater that they are still staged by major theater companies today. The Bacchae was Euripedes’ final play, performed posthumously at the festival in 405 BC.

The Bacchae is told from the perspective of Dionysus himself. In it, he has come to the city of Thebes, having heard that King Pentheus refuses to recognize the godhood of the Olympian. Dionysus begins teaching the women of Thebes his mysteries and to the rest of the city, they appear to go mad; they twine snakes in their hair, perform miracles, and tear cattle to shreds with their bare hands.

In disguise, Dionysus persuades the king to spy on the women rather than confront them head-on. Being so close to the god, the king slowly goes mad. He sees two suns in the sky and believes he sees horns growing from the man with him. Once near the women, Dionysus betrays the king, pointing him out to his “maenads”. The women, led by the King’s mother, tear the monarch apart and parade his head through the streets. As they do so, the madness that surrounds the woman leaves her, and she realizes what she has done. The play ends with Dionysus telling the audience that things will only continue to get worse for the royalty of Thebes.

There is constant debate as to the true message of the play. Was it simply a warning against those who doubted the riotous god, or was there some deeper meaning about class warfare? Whatever the interpretation, The Bacchae is still considered one of the most important plays in theatrical history.

The Frogs

A comedy written by Aristophanes, The Frogs appeared at the City of Dionysus in the very same year as The Bacchae, and recordings from later years suggest it won first place in the competition.

The Frogs tells the story of a trip by Dionysus to the underworld. His trip is to bring back Euripides, who had only just passed away. In a twist from ordinary tales, Dionysus is treated as a fool, protected by his smarter slave, Xanthias (an original character). Full of humorous encounters with Heracles, Aeacus, and yes, a chorus of frogs, the play climaxes as Dionysus finds his goal arguing with Aeschylus, another Greek tragedian who had passed recently. Aeschylus is considered by some as important as Euripides, so it is impressive to note that this was debated even at the time of their deaths.

Euripides and Aeschylus hold a competition with Dionysus as a judge. Here, the Greek god is seen to take leadership seriously and eventually chooses Aeschylus to return to the overworld.

The Frogs is full of silly events but also has a deeper theme of conservatism that is often overlooked. While the new theater may be novel and exciting, Aristophene posits, that does not make it better than what he considered “the greats.”

The Frogs is still performed today and studied often. Some academics have even likened it to modern television comedies like South Park.

Bacchanalia

The popularity of the City of Dionysia, and the public perverting of the secret mysteries, eventually led to the Roman rituals now called the Bacchanalia.

Bacchanalia are said to have occurred around 200 BC onwards. Associated with Dionysus and his Roman counterparts (Bacchus and Liber), there is some question as to how much of the hedonistic events were in the worship of any god. The Roman historian Livy claimed that, at its height, Bacchanalia “rituals” were participated in by over seven thousand citizens of Rome, and in 186 BC, the senate even attempted to legislate to control the out-of-control revelers.

The earliest versions of bacchanalia did appear to be similar to the old Dionysian mysteries. Its members were only women, the rites were held at night and involved music and wine. However, as time progresses, bacchanalia involved both sexes, far more sexual behavior, and eventually violence. Claims were made that some members were incited to murder.

The senate took control of the so-called “cult of bacchanalia” and, surprisingly, was able to get it under control. Within only a few years, the mysteries appeared to move back underground and eventually seemed to disappear altogether.

Today, the term bacchanalia appears when discussing any party or event that involves particularly lascivious and drunken behavior. “Bacchanal” art refers to those works including Dionysus or satyrs, in a state of rapture.

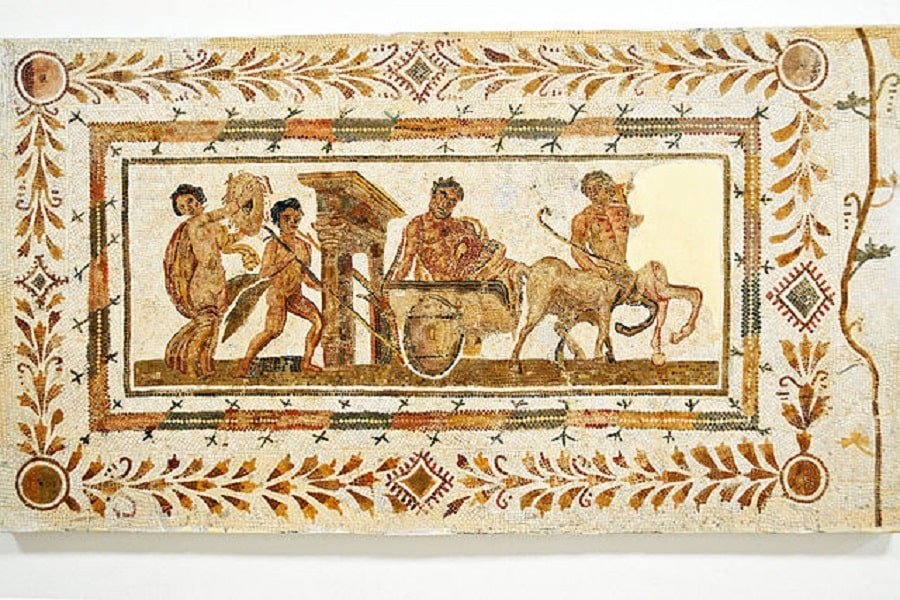

Dionysus in Greek and Roman Art

Some of the first appearances of the ancient Greek god and his followers were not in written or oral stories, but as appearing in visual art. Dionysus has been immortalized in murals, pottery, statues, and other forms of ancient art for thousands of years. It is not unexpected that many of the examples we have today are from jugs used to store and imbibe wine. Fortunately, we also have examples of art that include the remains of a temple to Dionysus, sarcophagi, and reliefs.

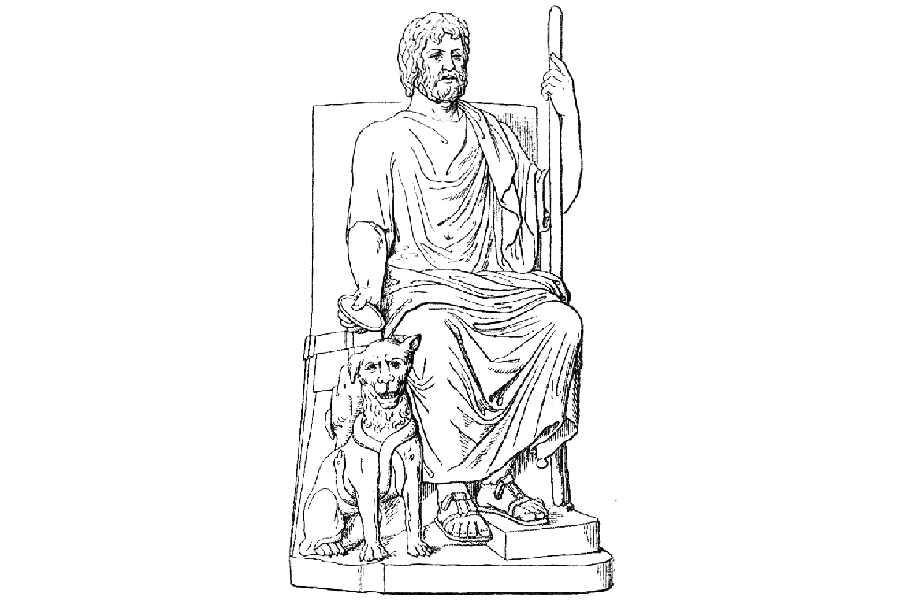

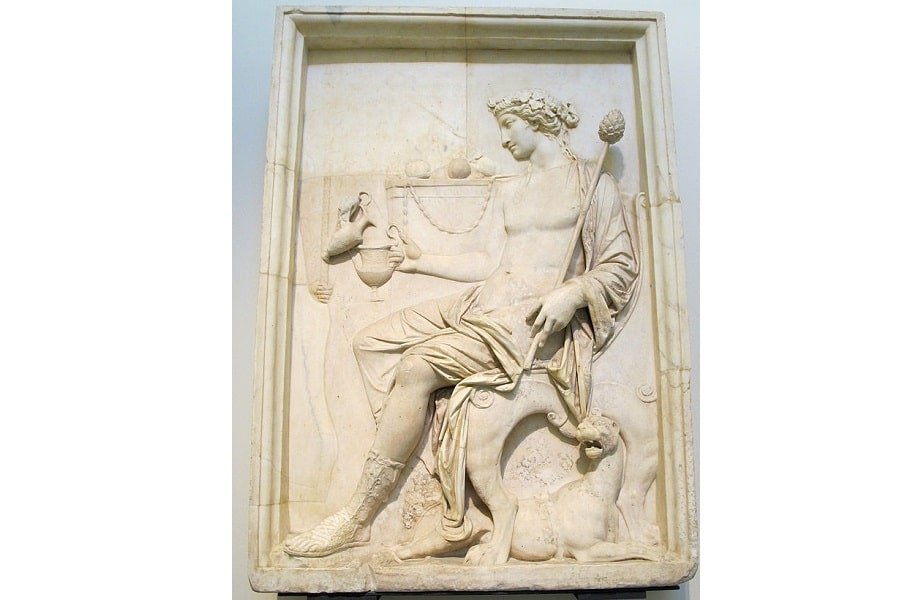

Dioniso Seduto

This relief shows one of the most common depictions of Dionysus in art. He holds the staff made from a fig tree, drinks wine from an ornate cup, and sits with a panther, one of the various mythological beings that formed a part of his retinue. While the facial features of the Greek god are effeminate, the body is far more traditionally manly. This relief could very well have been found on the wall of a temple devoted to Dionysus, or in a theater in Roman times. Today, it can be found in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, Italy.

Ancient Vase Circa 370 BC

This ancient vase was likely used to hold wine during rituals celebrating the Greek god. The vase shows Dionysus holding the mask of a woman, reflecting his androgynous appearance, while he rides a panther. Satyrs and Maenads (female worshipers of Dionysus) also appear. On the other side of the vase is Papposilen, the Roman form of Silenus (the teacher and mentor of child Dionysus). More information about Silenus and his relationship with Dionysus can be seen here, in a discussion about early coins that also portrayed the pair.

Hermes and the Infant Dionysus

An ancient Greek sculpture from the fourth century BC, this is one of the more famous examples of works that feature Hermes looking after the infant Dionysus. Strangely, considering the story we know of why Hermes was protecting the young Greek god, this statue was found in the ruins of The Temple of Hera, in Olympia. In this, Hermes is the subject of the piece, with his features more carefully carved and polished. When first found, faint remains of pigment suggest his hair was colored bright red.

Marble Sarcophagus

This marble sarcophagus is from circa 260 AD, and is unusual in design. Dionysus is on the ever-present panther, but he is surrounded by figures representing the seasons. Dionysus is quite an effeminate god in this portrayal, and as this was long after the mysteries had evolved into the world of theater, it is likely his presence was in no way a sign of worship.

Stoibadeion on the Island of Delos

We are quite fortunate today to still have access to an ancient temple dedicated to Dionysus. The temple at Stoibadeion still has partially erect pillars, reliefs, and monuments. The most famous of these monuments is the Delos Phallus Monument, a giant penis sitting on a pedestal adorned with the characters of Silenus, Dionysus, and a Maenad.

Delos has its own place in Greek mythology. According to Homer’s Odyssey, Delos was the birthplace of the Greek gods Apollo and Artemis. According to contemporary histories, the ancient Greeks “purged” the island to make it sacred, removing all previously buried corpses and “banning death.”

Today, less than two dozen people live on the island of Delos, and excavations continue to discover more about the temples found in the ancient sanctuary.

Dionysus in Renaissance Art and Beyond

The Renaissance saw a resurgence in art depicting the mythology of the ancient world, and the wealthy of Europe spent a fortune on works from those now known as the Masters, the great artists from this time period.

In these works, Dionysus was portrayed both as an effeminate god and a manly god, and his erotic nature inspired many works that never carried his name. Paintings of bacchanalia were also popular, though emphasizing the drunken, hedonistic nature of people rather than mystic worship. It should be noted that for almost all Renaissance works, Dionysus is referred to by his Romanized name, as one might expect as most buyers were Italian or church officials.

Bacchus by Michaelangelo

Perhaps the most important modern piece to feature the Greek god, this two-meter tall, marble statue was commissioned by Cardinal Raffaele Riario. Upon seeing the finished product, the cardinal promptly rejected it for too realistically depicting the drunken god.

Michelangelo took his inspiration for the piece from a short description of a lost artwork by Pliny the Elder. Behind him, a satyr eats from a bunch of grapes from the hand of the Olympian god.

Michelangelo’s work was not well received for many centuries, with critics unhappy with how “ungodlike” Dionysus is depicted. Today, replicas adorn gardens and streets around the world, while the original resides at Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Four years after the creation of “Bacchus,” Michelangelo would go on to carve his most famous work, which bears many striking similarities. Today, Michelangelo’s “David” is considered one of the most recognizable statues in the world.

Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian

This beautiful Renaissance painting captures the story of Dionysus and Ariadne, as told by Ovid. In the far left background, we see Theseus’ ship as he has abandoned her on Naxos, where the Greek god has been waiting for her. Painted for the Duke of Ferrera in 1523, it was originally commissioned from Raphael, but the artist died before finishing the initial sketches.

The painting offers a different look at Dionysus, presenting a more effeminate god. He is followed by a retinue of various mythological beings and pulled by a chariot of cheetahs. There’s a sense of wild abandonment to the scene, an attempt perhaps at capturing the ritual madness of the original mysteries. Titian’s version of Dionysus was a major influence on many later works, including Quiellenus’ piece covering the same topic one hundred years later.

Today, Bacchus and Ariadne can be found at the National Gallery, London. It was famously referred to by John Keats in “Ode to a Nightingale.”

Bacchus by Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens was an artist of the seventeenth century, and one of the few to be producing works from Greek and Roman biography despite their popularity falling off at the end of the Renaissance. His depiction of Bacchus is well worth noting for being quite different from anything before it.

In Ruben’s work, Bacchus is obese and looks not quite as much a riotous god as previously depicted. The painting seems at first to offer a more critical view of hedonism, but this is not the case. What drove this change from Ruben’s previous depictions of the Greek god is unknown, but based on his writings at the time, as well as his other works, it appears that, to Rubens, this painting was “a perfect representation of the cyclical process of life and death.”

Dionysus has been covered at some point or another by all the great European artists, including Caravaggio, Bellini, Van Dyk, and Rubens.

Modern Literature, Philosophy, and Media

Dionysus has never been out of the public consciousness. In 1872, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in The Birth of Tragedy, that Dionysus and Apollo could be seen as distinct opposites. The orgiastic worship of Dionysus was unrestrained, irrational, and chaotic. The rituals and rites surrounding Apollo were more ordered and rational. Nietzche argued that the tragedies of ancient Greece, and the beginning of theater, came from a coming together of the two ideals the Greek gods represented. Nietzche believed that the worship of Dionysus was based on a rebellion against pessimism, as evidenced by his followers being more likely to come from marginalized groups. In the late nineteenth century, the use of Dionysus as a shorthand for rebellion, irrationality, and freedom became popular.

Dionysus would pop many times in 20th-century popular entertainment. In 1974, Stephen Sondheim co-created an adaptation of The Frogs, in which Dionysus must instead choose between Shakespeare or George Bernard Shaw. Dionysus’ name comes up in many songs and albums from pop stars, the most recent being in 2019.

The Korean boy band, BTS, considered one of the most popular pop groups ever, performed “Dionysus” for their album, Map of the Soul: Persona. The song has been described as a “booze-filled rager.” It seems that even today, Dionysus is remembered more for his creation of wine, than the mystical worship that encouraged his followers to believe in freedom.

Conclusion

The god Dionysus is today best known for his role in creating wine, and for inspiring parties of hedonistic debauchery. However, for the Ancient Greeks, Dionysus offered more. The ancient Greek god was one connected to the seasons, rebirth, and freedom of sexual expression. An ancient queer icon, perhaps today we can think of Dionysus less as an animalistic Greek god, and more as an expression of true love.

Further Reading

Ovid, ., & Reilly, H.T. (1889). The Metamorphoses of Ovid. Project Gutenberg.

Nonnus, ., & Rouse, W.H. (1940). The Dionysiaca. Harvard University Press. (Accessible Online).

Siculus, ., & Oldfather, C.H. (1989). Bibliotheca Historica. Harvard University Press. (Accessible Online).

Images provided by WikiCommons unless otherwise noted.