Charon is a significant figure from Greek mythology associated with the realm of the dead. He is often depicted as an old, grim, and rugged figure with a long beard and tattered clothing, using a long pole to steer the ferry across the river. He is the ferryman of the underworld, responsible for transporting the souls of the deceased across the river Styx or the river Acheron to the afterlife.

Ghastly in appearance and superhuman in strength, he is prevalent in both Greek and Roman myth, notably retaining the same name in each and surviving in different forms and representations, up to the modern day.

Table of Contents

Who is Charon? Charon’s Role in Greek Mythology

Charon is perhaps the most famous of what is called a “psychopomp” (along with more modern interpretations such as the grim reaper) – which is a figure whose duty it is to escort deceased souls from earth to the afterlife. In the Graeco-Roman body of myth (where he mostly features) he is more specifically a “ferryman, escorting the deceased from one side of a river, or lake, (usually the Acheron or Styx) to the other, both of which lie in the depths of the underworld.

READ MORE: 10 Gods of Death and the Underworld From Around the World

Furthermore, he is supposed to be dutiful in this position, to ensure that those who cross are actually dead – and buried with the proper funeral rites. For escort across the river Acheron or the river Styx, he must be paid with coins that were often left on the eyes or mouth of the dead.

Origins of Charon and What He Symbolizes

As an entity, Charon was usually said to be a son of Erebus and Nyx, the primordial god and goddess of darkness, making him a god (although he is sometimes described as a demon). It was suggested by the Roman historian Diodorus Siculus that he originated in Egypt, rather than Greece. This makes sense since there are numerous scenes in Egyptian art and literature, where the god Anubis, or some other figure such as Aken, takes souls across a river into the afterlife.

READ MORE: Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

However, his origins may be even older than Egypt, as in Ancient Mesopotamia the river Hubur was supposed to run into the underworld, and it could only be crossed with the help of Urshanabi the ferryman of that ancient civilization. It may also be the case that there is no specific starting point discernible for Charon the ferryman, as similar motifs and figures populate cultures all over the world, on every continent.

READ MORE: The Cradle of Civilization: Mesopotamia and the First Civilizations

Nevertheless, in each culture and tradition, he symbolizes death and the journey made to the world below. Moreover, since he is often depicted as a gruesome, demonic figure he has come to be associated with the darker imagery of the afterlife and the undesirable fate of “eternal damnation” in some fiery form of hell.

Development of Charon in Graeco-Roman Myth

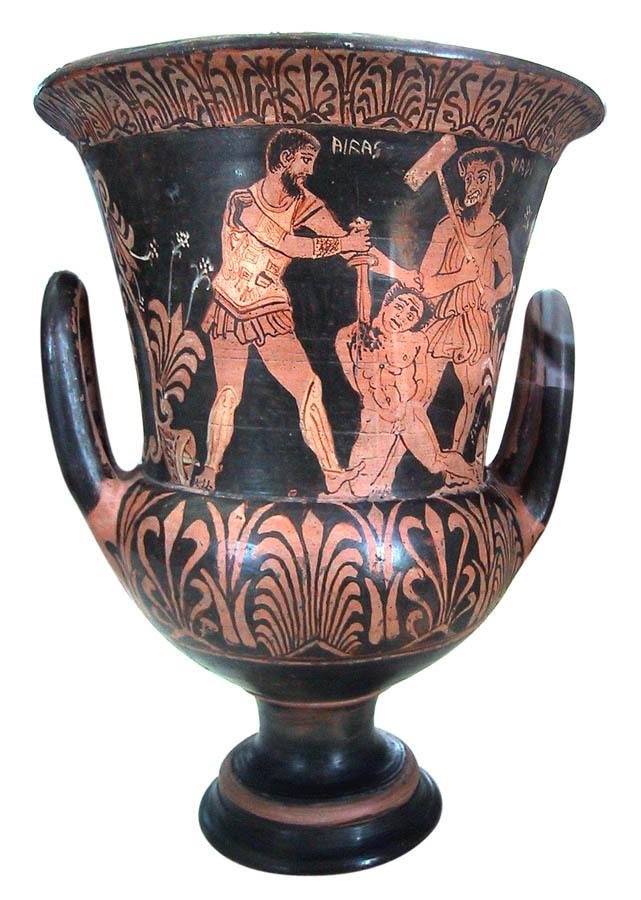

For Graeco-Roman culture more specifically, he first appears in vase paintings towards the end of the fifth century BC and was supposed to have appeared in Polygnotos’s great painting of the Underworld, dating from around the same time. A later Greek Author – Pausanias – believed that Charon’s presence in the painting was influenced by an even earlier play, named Minyas – where Charon was supposedly depicted as an old man who rowed a ferryboat for the dead.

There is, therefore, some debate whether he was a very old figure from popular belief, or that he was a literary invention from the archaic period when the great body of Greek myths began to proliferate.

READ MORE: Ancient Greek Art: All Forms and Styles of Art in Ancient Greece

In the Homeric works (the Iliad and the Odyssey), there is no mention of Charon as a psychopomp; instead, Hermes fulfills this role (and did on many subsequent occasions, often in conjunction with Charon). Later however, it seems that Hermes tended to often escort souls to the “nether regions,” before Charon would take charge of the process, escorting them across the rivers of the dead.

Post-Homer, there are sporadic appearances or mentions of Charon in various tragedies or comedies – first in Euripides’s “Alcestis,” where the protagonist is filled with dread at the thought of the “ferryman of souls.” Soon after, he featured more prominently in Aristophanes’s Frogs, wherein the idea that he requires payment from the living to pass across the river is first established (or at least seems to be).

Subsequently, this idea, that you would have to provide Charon with a coin for passage across the River Acheron/Styx, became intrinsically linked to Charon and was accordingly called “Charon’s Obol” (an obol being an ancient Greek coin). In order to make sure the dead were prepared for the expense, obols were supposedly left on their mouths or eyes, by those who buried them. If they did not come so equipped, as the belief goes, they would be left to wander on the banks of the river Acheron for 100 years.

After these early playwrights, and such associations as “Charon’s Obol,” the ferryman of souls came to be a rather popular figure in any Greek or Roman stories, plays, and myths that involved some aspect of the underworld. As noted above, he even retained his name in Roman literature.

READ MORE: Greek Mythology: Stories, Characters, Gods, and Culture

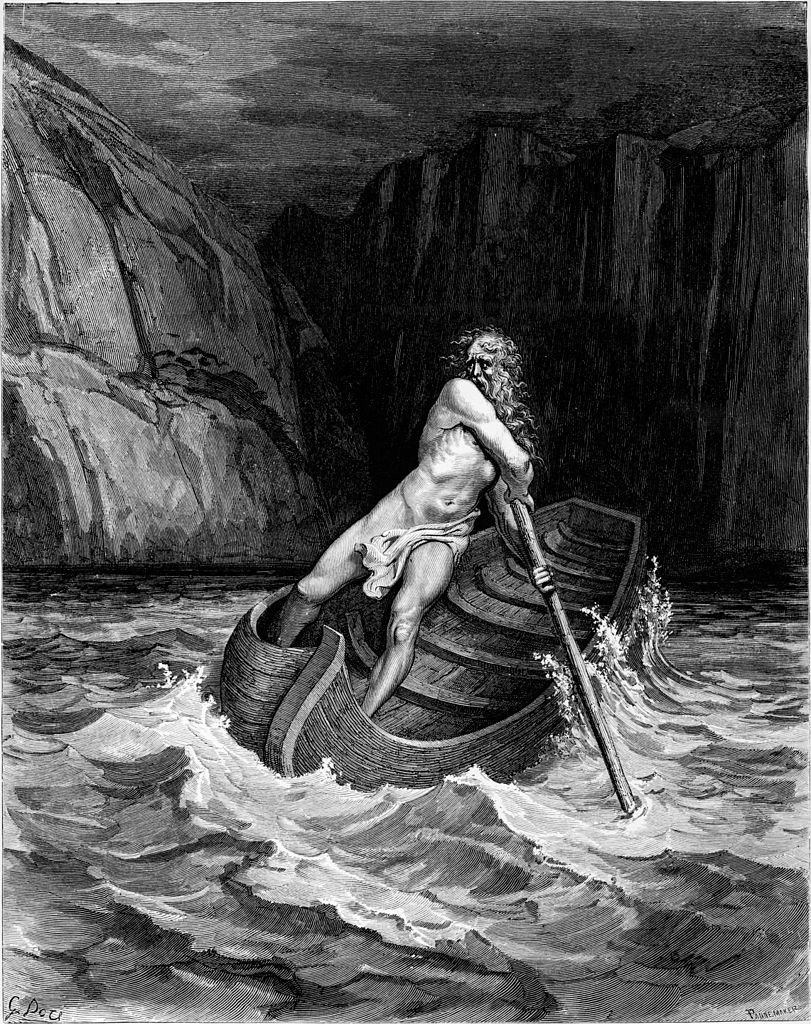

The Appearance of Charon

As far as gods or demons go, depictions of Charon have not been too generous. In his early presentations on vase paintings he appears quite generously as an old or mature man, with a beard and in plain clothes. However, in the imagination of later writers and artists, he is depicted as a decrepit and repulsive figure, donned in ragged and worn robes, often with glowing fiery eyes.

Much of this regressive turn in fact seems to be engineered by the Romans – as well as the Etruscans. Whilst depictions of Charon in Greek myth and art present him as a grim figure who has no time for trifles, it is his presentation as the closely equivalent Etruscan “Charun” and the Charon of Virgil’s Aeneid, that establish Charon as a truly demonic and detestable entity.

In the former representation under the Etruscans, “Charun” seems to take on some of the elements of their chthonic gods, as he is depicted with graying skin, tusks, a hooked nose, and a menacing mallet in his hand. It is thought that this mallet was included so that Charun could finish the job, so to speak – if those who he confronted on the banks of the river Acheron were not actually dead.

Then, when writing the Aeneid, Vergil took up this menacing and gruesome depiction of Charon that seemed to be in vogue with contemporary writers. Indeed, he describes the “terrible Charon in his filthy rags” as having “glaring eyes..lit with fire”, as he “he plies the [ferry] pole and sees to the sails as he ferries the dead in a boat the color of burnt iron”. He is a cantankerous character in the epic, initially irate at the presence of the living Aeneas trying to enter the domain he guards.

Later, this presentation of Charon as a demonic and grotesque figure seems to be the one that sticks and is later taken up in medieval or modern imagery – to be discussed more below.

Charon and the Ancient Katabasis

As well as discussing Charon’s role, it is important to discuss the type of works or narratives that he is usually depicted in – namely the “Katabasis.” The Katabasis is a type of mythical narrative, where the protagonist of the story – usually a hero – descends into the underworld, in order to retrieve or obtain something from the dead. The corpuses of Greek and Roman myths are littered with such stories, and they are essential for fleshing out Charon’s character and disposition.

Usually, the hero is granted passage to the underworld by propitiating the gods in some act or ceremony – not so for Heracles. Indeed, the famous hero Heracles instead barged his way through, forcing Charon to ferry him across the river in a rare example of Charon not observing proper protocol. In this myth – depicted by various writers, whilst Heracles is completing his twelve labors – Charon seems to shrink from his duty, in fright of the hero.

For this discrepancy, Charon was apparently punished and kept for a year in chains. In other katabases, it is, therefore, no surprise that Charon is always assiduous and officious in his duties, questioning each hero and asking for the proper “paperwork.”

In the well-known comedy play “Frogs,” written by Aristophanes, a forlorn god Dionysos descends into the underworld in order to find Euripides and bring him back to life. He also brings his slave Xanthias who is refused access across the river by the curt and insistent Charon, who mentions his own punishment for allowing Heracles to cross the grim river.

In other plays and stories, he is just as blunt and stubborn, taking some across the river whilst refusing passage to others. However, the gods sometimes grant passage to mortals still alive to pass through the underworld, such as the Roman hero Aeneas – who is provided with a golden branch that allows him to enter. Begrudgingly, Charon lets the founder of Rome cross the river so that he can speak with the dead.

Elsewhere, Charon’s character is sometimes satirized, or at least he plays the part of the stubborn figure who does not have time for the comedic aspects of another protagonist. For example, in the dialogues of the dead (by the Graeco-Roman poet Lucian), Charon does not have time for the insufferable Cynic Mennipus, who has come down to the depths of the underworld to insult the dead aristocrats and generals of the past.

In the work eponymously titled “Charon” (by the same author), Charon reverses roles and decides to come up to the world of the living to basically see what all the fuss is about. Also called “the follies of mankind”, it is a comical take on the affairs of humankind with Charon in an ironic position being the one to assess them all.

Charon’s Later Legacy

Whilst the exact reasons are not clearly explained, some aspects of Charon’s character or appearance were so appealing (in some sense) that he was regularly depicted in later medieval, renaissance, and modern art and literature. Moreover, the idea of Charon’s Obol has endured throughout history as well, as cultures have continued to place coins on the mouths or eyes of the deceased, as payment for the “ferryman.”

Whether this practice derives in a given example from the Greek ferryman (Charon) or some other ferryman, “Charon’s Obol” and Charon, in general, has become the most popular or common figure for the practice to be associated with.

Additionally, Charon has been regularly featured in subsequent art and literature, from medieval paintings and mosaics to modern films about Heracles/Hercules. In Hercules and the Underworld, or Disney’s Hercules, his grim and grotesque representations reflect the depictions made by the later Roman writers.

He also features in the world-famous work of Dante Alighieri – the Divine Comedy, specifically in the Inferno book. Like the modern adaptations, he is a grim figure with black eyes who ferries Dante and Virgil across the river to the land of the dead in a depiction that probably helped to immortalize Charon in popular imagination forever, as he has since been synonymized with anything relating to death and its arrival.

Whilst he shares many similar characteristics with figures like the grim reaper, he has survived even more intact in modern Greek folklore and tradition, as Haros/Charos/Charontas. All of these are very close modern equivalents to the ancient Charon, as they visit the recently deceased and bring them to the afterlife. Or else he is used in modern Greek phrases, such as “from the teeth of Charon”, or “you will be eaten by Haros”.

Like other gods or ancient mythological beasts and demons of myth, he also has a planet (or more specifically a moon) named after him – one which very appropriately circles the dwarf planet Pluto (the Roman equivalent of Hades). It’s therefore clear that the interest and appeal of the morbid ferryman of the dead is still very much alive in modern times.

READ MORE: 10 Gods of Death and the Underworld From Around the World