Ancient Greek art refers to the art produced in ancient Greece between the 8th century BC and the 6th century AD and is known for its unique styles and influence on later Western art.

From geometric, archaic, and classical styles, some of the most famous examples of ancient Greek art include the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to the goddess Athena in Athens, the sculpture of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, Venus de Milo, and many others!

Given that the post-Mycenaean era of Ancient Greece covers a span of almost a thousand years and includes Greece’s greatest cultural and political ascendancy, it’s no surprise that even the surviving ancient Greek artifacts represent a staggering array of styles and techniques. And with the various mediums the ancient Greeks had at their disposal, from vase painting to bronze statues, the breadth of ancient Greek art in this period is even more daunting.

Table of Contents

Styles of Greek Art

Ancient Greek art was an evolution of Mycenaean art, which predominated from about 1550 BCE to about 1200 BCE when Troy fell. After this period, Mycenaean culture faded, and its signature art style stagnated and began to dwindle.

This set Greece into a languid period known as the Greek Dark Ages, which would last some three hundred years. There would be little to no innovation or genuine creativity during most of this period – just the dutiful imitation of preexisting styles, if that – but that would begin to change about 1000 BCE as Greek art arose, moving through four periods, each with trademark styles and techniques.

Geometric

During what is now called the Proto-Geometric Period, pottery decoration would be refined, as would the art of pottery itself. Potters began using a fast wheel, which allowed for much more rapid production of larger and higher quality ceramics.

READ MORE: 15 Examples of Fascinating and Advanced Ancient Technology You Need To Check Out

New shapes began to emerge in pottery while existing forms like the amphora (a narrow-necked jar, with twin handles) evolved into a taller, slenderer version. The ceramic painting also began to take on a new life in this period with new elements – chiefly simple geometric elements like wavy lines and black bands – and by 900 BCE, this increasing refinement officially pulled the region out of the Dark Ages and into the first recognized era of ancient Greek art – the Geometric Period.

The art of this period, as the name implies, is predominated by geometric shapes – including in the depictions of humans and animals. Sculptures of this era tended to be small and highly stylized, with figures often presented as collections of shapes with little attempt at naturalism.

Decorations on pottery tended to be organized in bands, with the key elements in the widest area of the vessel. And unlike the Mycenaeans, who by the end had frequently left large blank spaces in their decorations, the Greeks adopted a style known as horror vacui, in which the entire surface of a ceramic piece was densely decorated.

Funerary Scenes

During this period, we see the rise of traditionally functional ceramics used as grave markers and votive offerings – amphorae for women and a krater (also a double-handed jar, but one with a wide mouth) for men. These memorial ceramics could be quite large – as much as six feet tall – and would be heavily decorated to commemorate the deceased (they would also commonly have a hole in the bottom for drainage, unlike a functional vessel, to distinguish them from the functional versions).

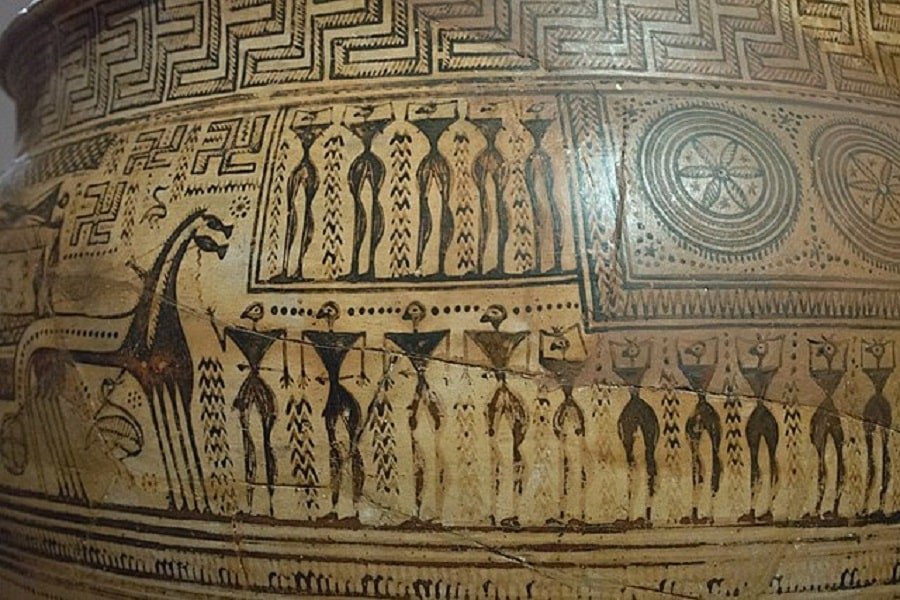

A surviving krater from the Dipylon Cemetery in Athens is a particularly good example of this. Called the Dipylon Krater or, alternately, the Hirschfeld Krater, it dates from approximately 740 BCE and seems to mark the grave of a prominent member of the military, perhaps a general or some other leader.

The krater has geometric bands at the lip and base, as well as thinner ones separating two horizontal scenes known as registers. Virtually every area of space between figures is filled with some sort of geometric pattern or shape.

The upper register depicts the prothesis, in which the body is cleaned and prepared for burial. The body is shown lying on the bier, surrounded by mourners – their heads simple circles, their torsos inverted triangles. Below them, a second level shows the ekphora, or funeral procession with shield-bearing soldiers and horse-drawn chariots marching around the circumference.

Archaic

As Greece moved into the 7th Century BCE, Near Eastern influences flowed in from Greek colonies and trading posts across the Mediterranean in what is known today as the “Orientalizing period” (roughly 735 – 650 BCE). Elements like sphinxes and griffins began to appear in Greek art, and artistic depictions began to move beyond the simplistic geometric forms of previous centuries – marking the beginning of the second era of Greek art, the Archaic Period.

READ MORE: Ancient Greece Timeline: Pre-Mycenaean to the Roman Conquest

The Phoenician alphabet had migrated to Greece in the previous century, allowing works like the Homeric epics to be distributed in written form. Both lyric poetry and historical records began to appear during this era.

And it was also a period of steep population growth during which small communities coalesced into the urban centers that would become the city-state or polis. All of this gave rise not only to a cultural boom but a new Greek mentality as well – to see themselves as part of a civic community.

Naturalism

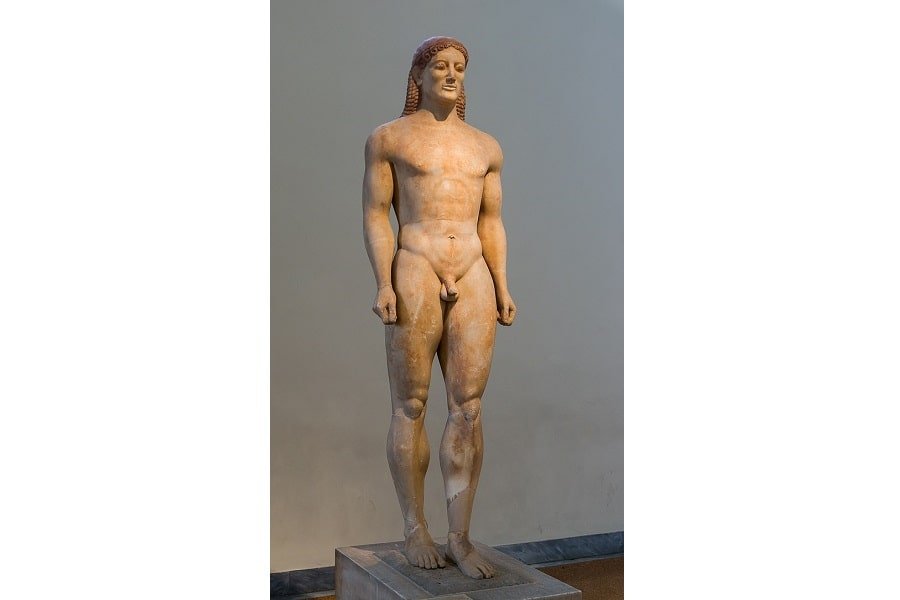

Artists in this period became much more concerned with correct proportions and more realistic portrayals of human figures, and there is perhaps no better representation of this than the kouros – one of the predominant art forms of the period.

A kouros was a free-standing human figure, almost always a young man (the female version was called a kore), generally nude and usually life-sized if not larger. The figure typically stood with the left leg forward as though walking (though the pose was in general too stiff to convey a sense of movement), and in many cases seem to bear a strong resemblance to Egyptian and Mesopotamian statuary which clearly provided inspiration for the kouros.

While some of the cataloged variations or “groups” of kouros still employed some amount of stylization, for the most part, they displayed substantially more anatomical accuracy, down to the definition of specific muscle groups. And statuary of all sorts in this era showed detailed and recognizable facial features – commonly wearing a happily content expression now referred to as an Archaic smile.

The Birth of Black-Figure Pottery

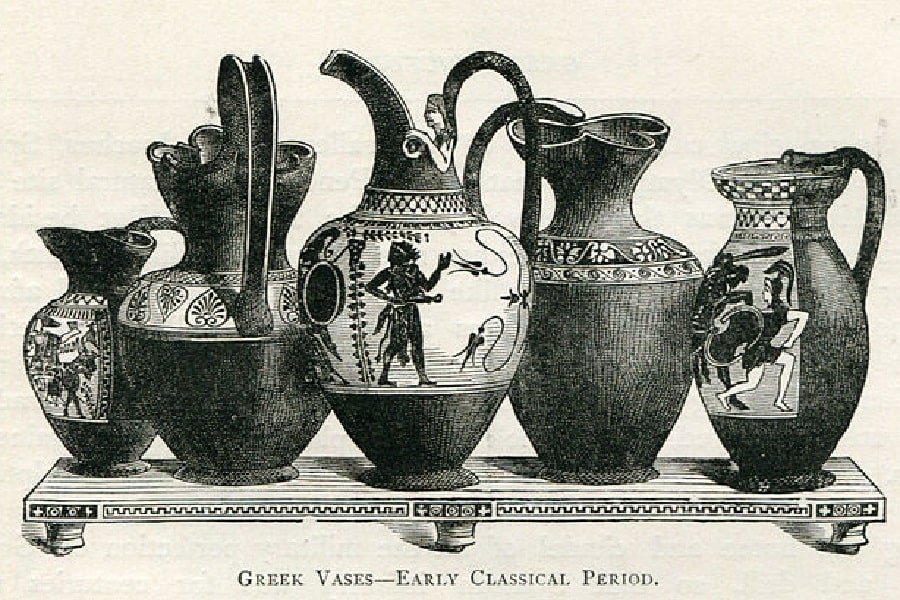

The distinctive black-figure technique in pottery decoration became prominent in the Archaic Era. First appearing in Corinth, it rapidly spread to other city-states, and while it was quite common in the Archaic Period, some examples of it can be found as late as the 2nd Century BCE.

In this technique, figures and other details are painted onto the ceramic piece using a clay slurry which was similar to that of the pottery itself, but with formulaic changes that would cause it to turn black after firing. Additional details of red and white could be added with different pigmented slurries, after which the pottery would be subjected to a complex three-firing process to produce the image.

Another technique, red-figure pottery, would appear near the end of the Archaic Era. The Siren Vase, a red-figure stamnos (a wide-necked vessel for serving wine), from about 480 BCE, is one of the better extant examples of this technique. The vase depicts the myth of Odysseus and crew’s encounter with the sirens, as related in Book 12 of Homer’s Odyssey, showing Odysseus lashed to the mast while sirens (depicted as woman-headed birds) fly overhead.

Classical

The Archaic Era continued into the Fifth Century BCE and is officially considered to have ended in 479 BCE with the conclusion of the Persian Wars. The Hellenic League, which had formed to unite the disparate city-states against Persian invasion, collapsed after the Persians’ defeat at Plataea.

READ MORE: The Battle of Marathon: The Greco-Persian Wars Advance on Athens

In its place, the Delian League – led by Athens – rose to unite much of Greece. And despite the strife of the Peloponnesian War against its Sparta-led rival, the Peloponnesian League, the Delian League would lead to the Classical and Hellenistic Periods which set off an artistic and cultural ascendancy that would impact the world ever after.

The famous Parthenon dates from this period, having been constructed in the latter half of the 5th Century BCE to celebrate Greece’s victory over Persia. And during this golden age of Athenian culture, the third and most ornate of the Greek architectural orders, the Corinthian, was introduced, joining the Doric and Ionian orders that had originated in the Archaic Period.

The Definitive Period

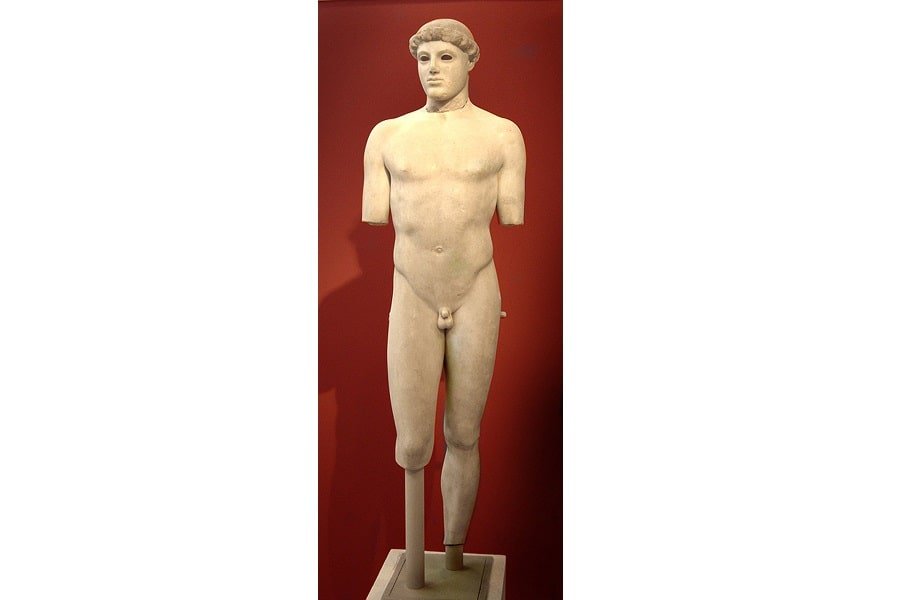

Greek sculptors in the Classical Period began to value a more realistic – if still somewhat idealized – human form. The Archaic smile gave way to more serious expressions, as both improved sculptural technique and a more realistic head shape (as opposed to the more block-like Archaic form) allowed more variety.

The rigid pose of the kouros gave way to a range of more natural poses, with a contrapposto stance (in which the weight is mostly distributed on one leg) quickly gaining prominence. This is reflected in one of the most significant works of Greek art – the Kritios Boy, which dates from about 480 BCE and is the first known example of this pose.

And the Late Classical Period brought another innovation – female nudity. While Greek artists had commonly depicted male nudes, it wouldn’t be until the Fourth Century BCE that the first female nude – Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos – would appear.

The painting also made great strides in this period with the addition of linear perspective, shading, and other new techniques. While the best examples of Classical painting – the panel paintings noted by Pliny – are lost to history, many other samples of Classical painting survive in frescoes.

The black-figure technique in pottery had largely been supplanted by the red-figure technique by the Classical Period. An additional technique called the white-ground technique – in which pottery would be coated with a white clay called kaolinite – allowed painting with a greater range of colors. Unfortunately, this technique seemed to enjoy only limited popularity, and few good examples of it exist.

No other new techniques would be created in the Classical Period. Rather, the evolution of pottery was a stylistic one. Increasingly, the classic painted pottery gave way to pottery made in bas-relief or in figural shapes such as human or animal forms, such as the “Woman’s Head” vase made in Athens about 450 BCE.

This evolution in Greek art didn’t just shape the Classical Period. They echoed down through the centuries not just as the epitome of Greek artistic style but as the foundation of Western art as a whole.

Hellenistic

The Classical Period endured through the reign of Alexander the Great and officially ended with his death in 323 BCE. The following centuries marked Greece’s greatest ascent, with cultural and political expansion around the Mediterranean, into the Near East, and as far as modern-day India, and endured until about 31 BCE when Greece would be eclipsed by the ascension of the Roman Empire.

This was the Hellenistic Period, when new kingdoms heavily influenced by Greek culture sprung up across the breadth of Alexander’s conquests, and the Greek dialect spoken in Athens – Koine Greek – became the common language across the known world. And while the art of the period didn’t gain the same reverence as that of the Classical Era, there were still distinct and important advances in style and technique.

After the painted and figurine ceramics of the Classical Era, pottery veered toward simplicity. The red-figure pottery of earlier eras had died out, replaced by black pottery with a shiny, almost lacquered finish. A tan-colored slip, along with white paint, might be applied to such ceramics to create wreaths or other basic elements.

Decorations in relief were also common, and pottery was increasingly mold-made. And pottery in general tended to be more uniform and aligned with the shapes of metalware, which had become increasingly available.

And while little of Greek painting survived this era, the examples we do have give an idea of style and technique. Hellenistic painters increasingly included landscapes when environmental details had often been omitted or barely suggested previously.

Trompe-l’œil realism, in which the illusion of three-dimensional space is created, became a feature of Greek painting, as did the use of light and shadow. The Fayum Mummy portraits, the oldest of which date back to the First Century BCE, are some of the best-surviving examples of this refined realism that arose in Hellenistic painting.

And these same techniques were applied extensively to mosaics as well. Artists like Sosos of Pergamon, whose mosaic of doves drinking from a bowl was said to be so convincing that real doves would fly into it attempting to join the ones depicted, were able to reach amazing levels of detail and realism in what had in prior eras been a much clumsier medium.

The Great Age of Statuary

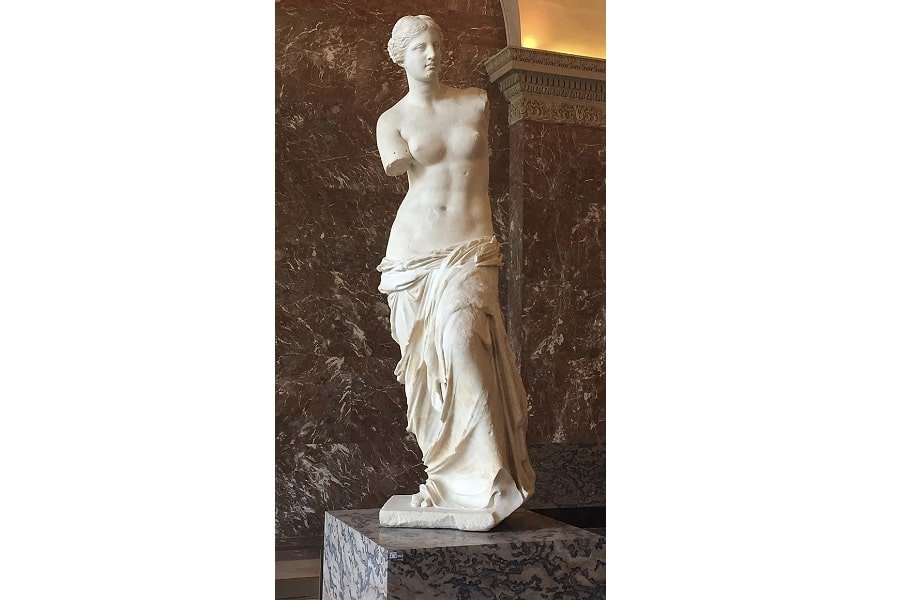

But it was in sculpture that the Hellenistic Period shined. The contrapposto stance endured, but a much greater variety of more natural poses appeared. Musculature, which had still felt stagnant in the Classical Era, now successfully conveyed movement and tension. And facial details and expressions became much more detailed and varied as well.

The idealization of the Classical Era gave way to more realistic depictions of people of all ages – and, in a more cosmopolitan society created by Alexander’s conquests – ethnicities. The body was now being displayed as it was, not as the artist thought it should be – and it was shown in rich detail as statuary became increasingly, painstakingly detailed and ornate.

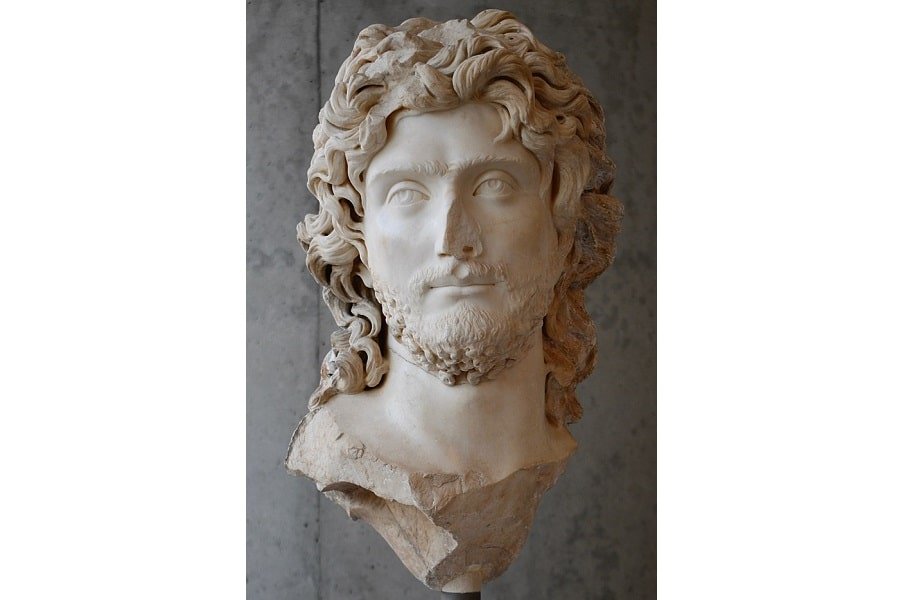

This is exemplified in one of the most celebrated statues of the period, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, as well as the Barberini Faun – both of which date from sometime in the 2nd Century BCE. And perhaps the most famous of all Greek statues dates from this period – the Venus de Milo (though it uses the Roman name, it depicts her Greek counterpart, Aphrodite), created sometime between 150 and 125 BCE.

Where previous works had generally involved a single subject, artists now created complex compositions involving multiple subjects, such as Apollonius of Tralles’ Farnese Bull (sadly, surviving today only in the form of a Roman copy), or Laocoön and His Sons (usually attributed to Agesander of Rhodes), and – in contrast to the earlier eras’ focus on harmony – Hellenistic sculpture freely emphasized one subject or focal point in preference to others.